Lessons from SPRING/Kyrgyz Republic

Imagine that two years into a nutrition project with a significant multi-channel social and behavior change communication (SBCC) component, you found that in roughly one-third of your coverage area, you were not reaching audiences or catalyzing changes as planned. Despite following a systematic behavioral design process, that was the situation faced by the SPRING project in the Kyrgyz Republic in late 2015. Because we were working with a supportive donor and had established positive working relationships with the Ministry of Health (MOH), national nongovernmental organizations, and thousands of community activists, we were able to make mid-course corrections, doing more of what was working and changing what wasn’t. In development, adapting interventions as needed is not always possible as a best practice. In this brief, we hope to help other programs embrace flexibility by discussing our experience adapting activities mid-way through a project.

Background

Kyrgyzstan is a lower-middle-income country that, despite high literacy rates and access to basic health services, has persistent stunting and anemia among women and children.1 Although women have relatively high levels of education and workplace participation, problems like early marriage and domestic violence exist.2 SPRING, which began in late 2014 and will end July 31, 2018, aims to reduce stunting and anemia among women of reproductive age and children younger than 2 years of age through the uptake of 11 high-impact evidence-based practices. Our activities include health system strengthening, supporting pro-nutrition policy development, SBCC, and enhancing year-round access to diverse diets through improved household food storage and preservation practices.

SPRING operates in Naryn and Jalalabad Oblasts, as well as the capital city of Bishkek. The public health system has excellent coverage and utilization, but the quality of services—especially in preventive nutrition—is inconsistent. SPRING’s activities include nutrition policy development at the national level, building the capacity of health providers in hospitals and primary care facilities to provide nutrition assessment and counseling services, and strengthening nutrition in pre-service education for doctors and nurses.

Developing an SBCC Strategy

In collaboration with the MOH and the Republican Center for Health Promotion (RCHP), SPRING developed an initial SBCC strategy based on results of a needs assessment, baseline survey data, and formative research. During field assessments, we worked with health promotion units (HPUs)—local representatives of the RCHP—and learned about a cadre of community volunteers known as “activists.” SPRING decided to use these activists instead of assembling separate teams of community volunteers because activists come from a variety of backgrounds (e.g., teachers, housewives, retirees, local government representatives) and have access to diverse community groups. The strategy was designed to ensure that the SBCC content and activities would be appropriate and feasible for the activists.

SPRING partnered with the Kyrgyz Association of Village Health Committees (KVHC) to mobilize, train, and support over 3,200 activists from communities in Jalalabad and Naryn. KVHC local coordinators are supervised by SPRING community mobilizers. KHVC is a unique organization with a mandate to work with a large network of 1,612 village health committees (VHC) and 58 rayon health committees (RHC) across the country. KVHC builds the capacity of VHCs and RHCs to do business planning and fund community health activities.

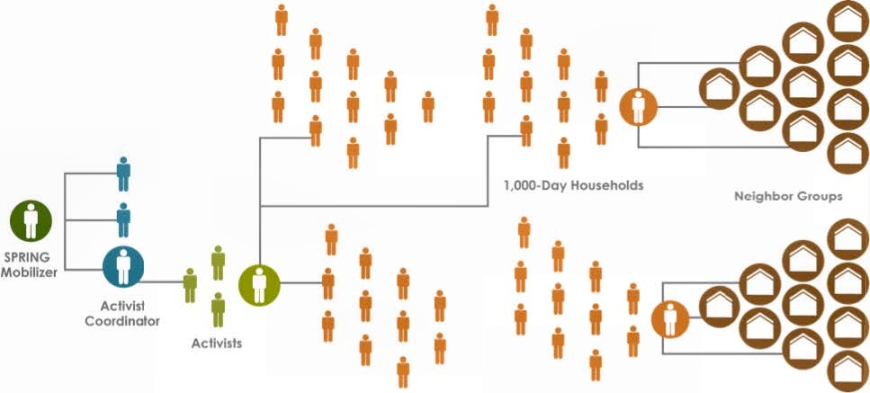

Figure 1. SPRING Model for Covering 1,000-Day Households and Communities

SPRING designed an initial orientation for activists that included introductions to the project and the importance of nutrition. After discussing their role on the project, activists organized themselves into groups and conducted community mapping. SPRING developed modules based on the evidence-based practices at the heart of its SBCC strategy, and volunteers rolled them out through household visits and community meetings.

Table 1. Community Activist Training Modules, Job Aids, and Module-related SBCC Materials

| Module No. | Module Topic | Materials for Trainer | Materials for Activists |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Activist mobilization, mapping, action planning | Mapping tools | Monitoring and reporting forms |

| 2 | Exclusive breastfeeding | Booklet (Nutrition and Development for Children under 2 years of Age) | Booklet (Nutrition and Development for Children under 2 years of Age) |

| 3 | Complementary feeding of young children | Cookbook (Healthy Nutrition for Children and the Whole Family) SPRING demonstration cup | Cookbook (Healthy Nutrition for Children and the Whole Family) SPRING demonstration cups |

| 4 | Handwashing and clean latrines | Leaflet (Clean latrines and Handwashing) | Leaflet (Clean Latrines and Handwashing) |

| 5 | Household dietary diversity | Dietary Diversity Handout –(includes food pyramid with 10 steps of healthy nutrition), food cards | Dietary Diversity Handout (includes food pyramid with 10 steps of healthy nutrition) |

| 6 | Anemia prevention | Two-Year Anemia Calendar Iron–Folic Acid Commitment Card | Two-Year Anemia Calendar Iron–Folic Acid Commitment Card |

| 7 | Maternal nutrition | Leaflet (Healthy Nutrition for Mothers to Promote the Growth and Development of Your Baby) | Leaflet (Healthy Nutrition for Mothers to Promote the Growth and Development of Your Baby) |

| 8 | Storage and preservation of healthy foods | Food Storage Guidebook | Food Storage Guidebook |

| 9 | Deworming and prevention of helminth infections | Deworming Leaflet for Families | Deworming Leaflet for Families |

| 10 | Strengthening community work | Communication tools | N/A |

| 11 | Refresher module on dietary diversity with a focus on reducing junk food | Dietary Diversity Handout food cards | Dietary Diversity Handout |

Training modules are spaced about 6–8 weeks apart and are held annually both for new activists and as refresher training for veteran activists. These trainings also build activists’ listening, counseling, and small-group facilitation skills, and teach them to use topical SBCC materials during home visits and community meetings.

Challenges Surface

Though our initial formative research showed similar types of community volunteers in both urban and rural areas, our supervision and monitoring data indicated that recruiting and retaining volunteer nutrition activists in urban areas was considerably more difficult than in rural areas. In part, this was due to the faster pace of urban life. Urban recruits didn’t have time for household visits or community meetings. Further, household visits weren’t as acceptable to urbanites, who were more skeptical about trusting nutrition advice from non-medical professionals. Similarly, the urban versions of HPUs were newly established and placed less emphasis on community outreach and more emphasis on institutional channels like schools. KVHC attempted to engage in urban areas through public health committees but met similar challenges and was unsuccessful.

Responding to Challenges

Building on Established Relationships

Throughout SPRING’s first two years of operation, the project worked very closely on its SBCC strategy design and implementation with RCHP. Capacity-building with RCHP, including workshops on SBCC strategy and materials design, is ongoing, and RCHP was instrumental in the development and approval of our activist training and SBCC materials. We had built trust and a good day-to-day working relationship with key staff there.

As we realized that we needed to adapt our SBCC strategy for urban audiences, RCHP asked for support to develop an MOH SBCC strategy focused on the 1,000 days. We requested that the strategy focus on urban areas, and RCHP agreed. Now SPRING’s urban SBCC activities are nested within the MOH SBCC strategy, which means they will extend beyond the life of the SPRING project. In 2018, we have been working with RCHP to update the strategy and extend it until 2020, building on lessons from the current strategy. The MOH is expanding the strategy to cover all regions, rural and urban areas, and more groups of stakeholders, while retaining a focus on improved maternal and child nutrition during the 1,000 days.

SPRING also worked with the MOH to improve quality of nutrition services available in urban areas through health care worker training, supportive supervision, and technical support to help health facilities gain baby-friendly certification. SPRING’s policy work also further improved what was already an enabling environment for nutrition services in urban areas, leading to the adoption of preventive iron-folic acid (IFA) supplementation for pregnant women and routine deworming policies.

Tailoring SBCC Activities to Urban Audiences and Partners

The people we most want to reach with urban SBCC activities include newly married couples (a group that includes some older adolescents), pregnant women, and mothers with children younger than 2 years of age. SBCC activities also target influencers such as older women (including but not limited to grandmothers); health providers (doctors and nurses who provide facility-based counseling); HPU staff; media personnel from television news and talk shows, print, radio, and social media channels; and local authorities including village administration (ayil okmotu), town administration (mayor’s office), and rural/urban community councils.

Because many urban families and health workers are short on time, we focused on a subset of priority practices:

- exclusive breastfeeding, including family support from fathers and grandmothers

- women’s care and diet during pregnancy and lactation, including household dietary diversity and junk food reduction

- anemia control through improved handwashing and hygiene, presumptive deworming, and IFA supplementation.

SPRING and partners defined specific behavioral outcomes and included them in the urban SBCC strategy. We wanted urban audiences to—

- visit the SPRING/Kyrgyz Republic Facebook page and get information on good nutrition practices

- seek additional nutrition information from health providers

- access/ask for IFA supplements from providers in health facilities

- form intentions and make plans with family members to—

- take IFA supplements and practice good nutrition when planning a pregnancy and while pregnant and lactating

- exclusively breastfeed children at least until 6 months, then introduce complementary foods

- maintain clean latrines and good handwashing practices to prevent diseases.

SPRING invited regional HPU staff from outside its coverage areas to participate in nutrition SBCC trainings, which helped us reach new audiences: some who worked with SPRING began visiting primary schools to promote improved handwashing, hygiene, and sanitation using our SBCC materials.

Developing a National Brand Identity for the 1,000-Day Window of Opportunity

SPRING worked with the MOH to develop an official logo and brand for the 1,000-day window of opportunity. The logo, adapted by a Kyrgyz artist

Figure 2. The Kyrgyz Ministry of Health 1,000 Days Logo

and shown in Figure 2, now appears on most of SPRING’s print materials and at the end of videos developed for social and mass media. As part of the overall branding and tone of nutrition SBCC activities, support for best health and nutrition practices is described as a gift from husbands, grandmothers, and mothers to newborns—a gift that benefits the whole family now and in the future. Consistent marketing helps people associate various videos, events, and other SBCC materials with the 1,000 Days brand. This brand reminds them how important it is to keep mothers healthy and give children an optimum start in life. We hope that the RCHP, MOH, and other non-SPRING partners will continue to use the logo and other brand elements for nutrition SBCC activities.

Reaching Urban Audiences through Mass and Social Media, Regional Media, and Messenger Workshops, Concerts, and Community Events

SPRING used Facebook to establish an online presence for nutrition issues in the Kyrgyz Republic, make nutrition issues relatable to Kyrgyz mothers and families through videos and success stories, and to complement mass media and community-based channels. Our Facebook content is tailored to urban audiences, but we anticipate an amplifying effect in rural areas because data show that while Internet use in the Kyrgyz Republic is disproportionately higher in urban areas, it is growing rapidly in rural regions.3

Live action and animated videos posted on our Facebook page and broadcast on regional television aimed to strengthen social norms around family support for mothers’ and children’s nutrition, and remind audiences of key diet, handwashing, and care practices. By December 2017, more than 183,000 individual Facebook users had seen SPRING videos (see Table 2). Our mass media activities focused on regional television networks, which cover our implementation areas. This work continues in 2018 with the introduction of videos of a celebrity chef preparing some of the recipes from SPRING’s popular family cookbook, two new videos for dissemination on regional TV and through Facebook, and a series of videos on key messages for the priority practices that MOH will broadcast on national TV.

Table 2. SPRING/Kyrgyz Republic Video Topics

| Video Topics | |

|---|---|

| Cooking shows demonstrating recipes for children 6–12 months | |

| Cooking shows demonstrating recipes for children 12 months and older | |

| Cooking shows demonstrating recipes for the whole family | |

| Animated videos promoting priority behaviors | |

| Live action videos promoting priority behaviors | |

| Pumpkin puree | Buckwheat porridge |

| Apple puree and pear puree | Lentil soup with chicken |

| Rice with pumpkin | Bulamyk (national porridge) |

| Kotlety for babies (minced meat with vegetables) | Soup with meatballs |

| Cauliflower | Vegetable salad |

| Zucchini and eggplant salad | Ukrainian Borscht (meat soup with vegetables) |

| Mash-ordo soup (beans, rice, and vegetables) | Carrot salad and beet salad |

| Chickpeas with meat | |

| Junk food reduction | Clean latrines |

| Nutrition in the first 1,000 days | The importance of exclusive breastfeeding |

| Handwashing and hygiene | Preventing worm infection |

| IFA supplementation | Exclusive breastfeeding |

| Diverse diets | |

Among the most high-profile activities of the urban SBCC strategy were professionally produced celebrity concerts attended by 9,000 people, predominantly young 1,000-day families, over two weeks. These shows raised the profile of nutrition issues and were a fun and memorable way to deliver pro-nutrition messages to audiences.

In addition to the concerts, urban community events included fun runs and meetings with singing, competitions, quizzes, and dancing. These events promoted handwashing, dietary diversity, and anemia and helminth infection prevention. SPRING also celebrates gender week annually with campaign events that engage men and grandmothers and recognize the importance of mothers’ health and well-being. During these events, fathers are encouraged to commit to practicing a new behavior that will help their children be healthy and grow well. Furthermore, SPRING nutrition and media experts used data, messages, and storytelling techniques to coach regional journalists, radio, and TV personalities on nutrition during the 1,000-day window.

Changing Behaviors in Rural and Urban Areas: Program Results

SPRING and its partners’ multi-channel adaptive SBCC activities have led to positive behavior changes for many of the 11 priority practices listed on page 2. Results included increased access to IFA supplements among pregnant women (from 80 to 84 percent in Naryn region and from 70 to 84 percent in Jalalabad region), higher rates of exclusive breastfeeding (from 15 to 63 percent in Naryn), and greater consumption of foods rich in vitamin A among children (from 23 percent at baseline to 34 percent at endline for Naryn and Jalalabad combined). These practices improved in part because SPRING tailored its SBCC activities to reach different audiences. Acknowledging that reaching people isn’t enough to catalyze change, we also made nutrition relevant and feasible for different types of “doers” and strengthened the pro-nutrition support network of community leaders, service providers, and other influencers.

Handwashing with soap and water at five critical times is one behavior that was change-resistant in both urban and rural areas. Neither knowledge nor practices increased in our intervention areas. Possible barriers to handwashing include: 1) the reluctance of community volunteers to talk with families about a behavior (or lack thereof) that might imply insufficient personal hygiene; and 2) cold weather through much of the year, which discourages handwashing at outdoor stations. Even during warm months, it can be challenging for family members who are moving livestock to mountain pastures to build and use latrines and/or handwashing stations. We are learning more through additional targeted qualitative research.

Our collaboration with KVHC will help sustain nutrition SBCC work in Kyrgyz Republic when SPRING ends. KVHC has integrated nutrition SBCC approaches into the way that it promotes improved practices and trained others to do so. KVHC is now a viable partner for other entities working on nutrition in rural and urban areas. In addition to the MOH and KVHC, SPRING SBCC approaches and materials are being replicated by other stakeholders including Mercy Corps, Good Neighbors, ACDI/VOCA, and the World Bank-funded Agricultural Productivity and Nutrition Improvement Project.

Conclusion

Partnership, Collaborative Learning, and Adaptation

When we realized that some of our SBCC activities were not working as expected in urban areas, we were able to correct course because SPRING has a strong partnership with the RCHP and worked closely with RCHP staff to to adapt activities for urban audiences. These efforts resulted in greater integration of nutrition SBCC into implementing partners’ missions and ways of working, leading to sustainability. In maintaining strong partnerships, it is important to remember that processes matter as much as outputs; collaborating with partners may take more time and effort, but it produces effective and sustainable resu lts. SPRING and its partners also learned that conducting formative research and developing a comprehensive strategy at the beginning of a project doesn’t mean that the project will never have to change—because contexts, audiences, and priority nutrition challenges change, ongoing project learning and evolution are necessary to maximize impact.

Leveraging Unique Characteristics of the Context

The Kyrgyz Republic is a unique context for maternal and child nutrition. It offers strong village, town, and city administration structures and a culture of volunteering for and participating in public health activities. High literacy rates, the relatively high status of women, strong traditional and growing social media, and accessible primary health services shaped SPRING’s work, not only at initial design, but throughout the project. Essentially, the enabling environment for improved household nutrition and hygiene behaviors is strong.

At the same time, before SPRING became active in the Kyrgyz Republic, maternal and child nutrition were not prioritized in public health campaigns or SBCC activities. We found that basic knowledge and awareness among mothers, fathers, caregivers, and health care workers were relatively low. The Kyrgyz Republic has proven to be a context where knowledge and information, if tailored and conveyed effectively, are enough to change many behaviors—unlike many places with environments that are not as enabling.

Building a Vision for the Future of Maternal and Child Nutrition

In a planning exercise for our final year, we asked SPRING community mobilizers what they hoped to see in communities one year after the project is completed. They hope that the videos developed with MOH will still be broadcast on television and shared through other social media channels once SPRING’s Facebook page is no longer being updated. They are confident that the stronger pro-nutrition health systems and policies, training resources, job aids, SBCC materials, and resources for improved food preservation and storage will continue to benefit 1,000-day families in these communities. Finally, they said, “We continue to have the capability and motivation to bring about social and behavior change for nutrition. We have to explore opportunities to do so.”

As we have worked with partners to implement urban and rural SBCC activities, we have noticed important intersections and complementarities among audiences. For example, rural and urban families meet and engage with their neighbors and community leaders; rural families use Facebook and would like to attend concerts like those offered in urban areas.

Ultimately, designing and implementing effective multi-sectoral nutrition SBCC approaches entails engaging people, meeting them where they are, building capacity with partners, and implementing memorable SBCC activities that promote feasible practices. Our dynamic and adaptive SBCC design, implementation, monitoring, and adaptive processes have advanced the nutrition needle in the Kyrgyz Republic. We look forward to seeing how others continue this important work.

Additional Resources

SPRING. n.d. Endline Nutrition Survey in the Kyrgyz Republic, Analytical Report. Arlington, VA: Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project. Forthcoming.

SPRING. 2017. Accelerating Behavior Change in Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture Online Training Course. Arlington, VA: Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project. Available at https://www.spring-nutrition.org/publications/training-materials/accelerating-behavior-change-nutrition-sensitive-agriculture.

SPRING. 2018. Kyrgyz Republic: Training Community Volunteers on Nutrition and Hygiene Module Toolkit. Arlington, VA: Strengthening Partnerships, Results,and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project. https://www.spring-nutrition.org/publications/training-materials/training-community-volunteers-nutrition-and-hygiene-module-toolkit

USAID. 2017. Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy 2014–2025 Technical Guidance Brief: Effective At-Scale Nutrition Social and Behavior Change Communication. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development.

Footnotes

1 National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic and MEASURE DHS/ICF International. 2012. Kyrgyz Republic Demographic and Health Survey, 2012. Bishkek, Kyrgyz Republic and Calverton, Maryland: Kyrgyz Republic Ministry of Health and MEASURE DHS/ICF International.

2 United Nations Development Programme. 2016. The Human Development Report, 2016. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme.

http://report.hdr.undp.org/

3 M-Vector Consulting Agency. 2013. Media Consumption and Consumer Perceptions Baseline Survey 2012, 2nd Wave. Bishkek, Kyrgyz Republic: M-Vector Consulting Agency.