SPRING has adapted guidance from several sources to develop a methodology for extracting nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive funding data from donor and government budget documents. This document is an annex to the Pathways to Better Nutrition (PBN) Case Study Series that outlines SPRING’s methodology and includes limitations of the data presented, as well as references for further information.

Background

The objective of SPRING’s “Pathways to Better Nutrition” (PBN) analysis of Uganda’s nutrition budgets is to provide stakeholders with:

- An estimate of funding budgeted for Ugandan Nutrition Action Plan (UNAP) activities in FY 2013/2014 and FY 2014/2015. This will be useful for comparison to the estimated costs to implement the UNAP plan, and for understanding gaps in nutrition funding. The data can also be used to plan government and donor nutrition funding, and to advocate for greater and more consistent nutrition funding.

- Information on which activities are prioritized financially each year within the UNAP. This includes information on funding sources for each activity, whether funding has been shifted from other activities, and the balance of government and donor funding for the nutrition activities.

- Budgeting tools and guidance to help nutrition stakeholders in Uganda more explicitly track and advocate for nutrition funding. This can help with reporting not only within Uganda but also for groups such as the “Scaling Up Nutrition” (SUN) Movement, which prioritizes financial tracking in its monitoring and evaluation of countries.

Defining Budget Analysis

Political will for nutrition must be reflected through financial support at the national and subnational level (USAID 2014). There are several steps involved in tracking financing support. Costing a national nutrition plan provides estimates for what amount of funding is necessary to implement nutrition activities; analysis of current budgets (government and donor) provides estimates for what funding is actually allocated to implement nutrition activities; analysis of expenditures to estimate what percent of allocated funds were spent; and expenditure tracking to find why funds did not reach their intended destination.

The World Bank, UNICEF, and other government partners are currently supporting the first step of this process—the re-costing of the UNAP in Uganda. SPRING is primarily focused on the second step: estimating what funding is allocated to implement the nutrition activities in the UNAP, and to the extent that there are available data, how much of that funding was spent. This is what SPRING generally means by ‘budget analysis’ for purposes of this brief.

Budget analysis can be defined as applied analysis of government and donor budgets with the explicit intention of impacting a policy debate or furthering policy goals (The International Budget Project 2001). This work can include efforts to improve budget literacy of policymakers, program planners, and other key stakeholders. In the case of Uganda, SPRING’s budget analysis is meant to better inform the stakeholders advocating for the UNAP of their available resources. This can lead to more effective advocacy for greater nutrition funding, more transparency in how those funds will be spent, and clearer negotiation for donor funding.

To the extent possible, SPRING is also addressing what percent of funds were spent for nutrition activities. This will depend on the data available in Uganda and the strength of the government expenditure tracking system. SPRING will not address the final step of identify the reasons behind anomalies in spending as this type of work is best done through other methods, such as the World Bank’s Public Expenditure Tracking Survey (PETS) or Public Expenditure Reviews.1

Defining Nutrition Activities

The scope of nutrition is quite difficult to define, yet a clear definition is needed for budget analysis and financial tracking. The UNAP is used as the definition of the boundaries of activities that can be included for this analysis. There are several advantages to this, as well as a few drawbacks.

The UNAP contains an explicit implementation matrix (Annex I of the UNAP) that defines the interventions in support of the UNAP, expected outputs, the government agency responsible for leading each activity, and other participants. There is also an approximate cost assigned to each activity in Annex II of the UNAP, and a revised costing exercise led by UNICEF, REACH, and the World Bank is currently underway. The advantages of using this scheme are that the activities are set for the five-year period of the UNAP, allowing SPRING to follow the same set of activities over that time. It also means that estimated financial allocation and expenditures can be compared to the costing for the plan. Finally, by having both teams work from the same document, it aligns the budget analysis with the qualitative assessment of prioritization.

One drawback is that some activities that SUN includes on its “nutrition-sensitive” list for the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) guidance will not be counted in our analysis. Each country has latitude to include or exclude any of these activities, and in the UNAP certain sectors received less emphasis. Qualitative enquiry can probe the reasons for the differences between the SUN definition and what appears as sensitive in the UNAP (see Appendix 1 for the SUN list), but for the budget analysis, excluded activities will not count toward the total estimated nutrition allocation or expenditure. Another drawback is that there is ambiguity on the UNAP list, allowing some subjectivity in interpretation.

SPRING has compiled a list of ambiguous terms and activities and has asked the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM, the UNAP Coordination Secretariat) and if necessary the lead agency to clarify the terms, but in some cases there is still room for interpretation. When this occurs SPRING allows the inclusion of any budget items related to that activity that still fall within the SUN definitions of nutrition-sensitive. All final budget lists are validated by the ministry or donor responsible, as a last check on the validity of the budget analysis.

Throughout the analysis, SPRING utilizes our in-country partner Deutsche Stiftung Weltbevoelkerung (DSW) for guidance on interpretation of budget documents and findings. DSW has decades of experience in budget analysis, both in Uganda and elsewhere, and provides SPRING with essential insight into local context of the budget process. They also have adapted their community-led process for district-level budget analysis to align with SPRING’s national-level methodology to provide comparable data in the two study districts (Lira and Kisoro). The modified methods for these results are outlined in their district-level report.

Methods

The PBN case study is a prospective mixed-methods study. Budget analysis to compare with results of the qualitative data on activity prioritization and feed further inquiry into planning for nutrition is an integral part of the study design. There are no standard documented methods for extracting budget data, especially for a subsector such as nutrition. For its methodology for extracting nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive funding data from donor and government budget documents, SPRING adapted guidance from several sources:

- SUN donor network guidance for tracking global investments in the Development Assistance Committee database (DAC) (SUN Donor Network 2013).

- Examination of the UNAP implementation matrix (Government of Uganda 2011).

- Advice on local budgeting procedures from SPRING’s in-country partners DSW, who have experience conducting cross-sector budget analysis in Uganda and elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa (Sizomu, Brucker, and Muwonge 2014).

- Consultation with the Ugandan government ministries and key donors

SPRING will collect and analyze budget data for two budget cycles: 2013/2014 and 2014/2015. Data will be collected at the national level for government, donor, and UN groups, and in two districts for government, donor, UN groups, and civil society organizations (CSOs).

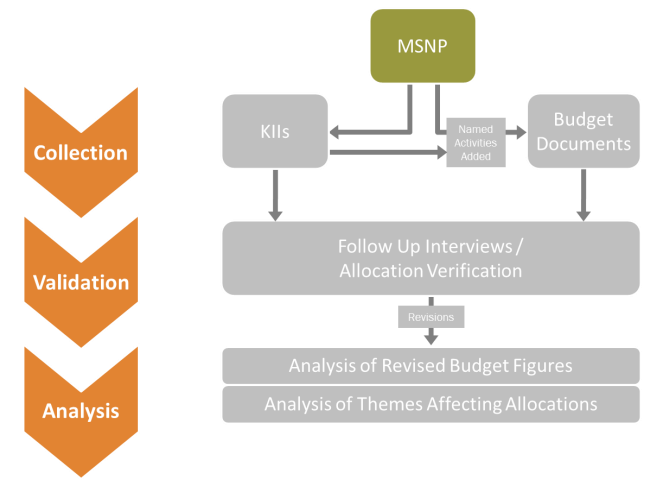

Figure 1: Summary of SPRING’s Budget Methodology

The process for data extraction and analysis described below was used to address Objectives 1 and 2 of the budget analysis. SPRING will document this process and develop tools to help others replicate this analysis by the end of the study to meet Objective 3.

Data Collection

National Level

National-level data were gathered during baseline data collection in November 2013 and will be repeated for the next budget cycle. The team conducted qualitative and budget interviews with stakeholders from the six key groups named by SUN for scaling up nutrition activities:

- Government (ministries as well as the nutrition coordinating body and office of the prime minister)

- Donor agencies

- CSOs (at national level, only the organizing body for CSOs, as more in-depth interviewing of this group occurs at the district level)

- Business/private sector

- UN groups

- Academic/research institutions

SPRING requested budgets, supplemental documents, work plans, and any other documents needed to identify nutrition funding for each of the groups bolded from the above list. For the other groups, SPRING inquired about approximate funding for their nutrition work and source of funding but did not pursue the full budgeting exercise.

There are overlapping funding lines in these groups, particularly for donor and UN agencies. Many bilateral donors provide funding to UN agencies and to the Government of Uganda. When funding UN agencies, bilaterals rarely identify the funding as nutrition, which means the UN agency decides how to allocate those funds within the larger category of giving. SPRING chose to follow donor and UN funds at the project level, rather than starting from the top, i.e., global allocation level. Off-budget donor and UN activities can be identified through the MOF’s “Summary of project support managed outside government systems.” This captures only off-budget financing. All on-budget financing of UNAP activities was identified within each government ministry’s work plan and ministerial policy statement, supplemented by responses from the qualitative interviews on funded on-budget activities by donors and UN agencies. These sources were cross-referenced by each ministry to identify on-budget nutrition activities and extracted data were validated by follow-up interviews with each ministry.

District Level

SPRING and subcontractor DSW conducted qualitative and budget interviews in April-August 2014 in the districts of Lira and Kisoro. DSW led the budget-related interviews and collected key documents, as was done by SPRING at the national level.

The following groups participated in the budget interviews:

- Government (national medical stores, Lira Referral hospital, and district officers of Kisoro and Lira)

- Donor agencies (if local office was in place)

- CSOs (all that operate nutrition-related projects in the two districts)

- UN groups (if local office was in place)

SPRING and DSW collected and reviewed district development plans, sector work plans, budget performance reports, CSO budget reports and work plans, hospital budgets and work plans, and local government work plans from both districts (the full list of district-level documents reviewed is provided in Appendix 4).

Data Processing and Analysis

National and District Level

Nutrition-Specific Activities

Within the sources above and the activities in the UNAP, SPRING largely follows the USAID Nutrition Strategy definition of nutrition-specific activities:

- Management of severe acute malnutrition

- Preventive zinc supplementation

- Promotion of breastfeeding

- Appropriate complementary feeding

- Management of moderate acute malnutrition

- Periconceptual folic acid supplementation or fortification

- Maternal balanced energy protein supplementation

- Maternal multiple micronutrient supplementation

- Vitamin A supplementation

- Maternal calcium supplementation

This matches the list provided in the executive summary of the 2013 Lancet Series (Lancet 2013). SUN guidance for the identification of nutrition-specific activities was also based on the Lancet Series’ (2008 and 2013) set of interventions.

The SUN guidance for tracking global investment in nutrition (Mucha 2012; SUN Donor Network 2013) does not provide a definition past use of the “basic nutrition” DAC purpose code. In the DAC, the definition of this code is:

Direct feeding programs (maternal feeding, breastfeeding and weaning foods, child feeding, school feeding); determination of micro-nutrient deficiencies; provision of vitamin A, iodine, iron etc.; monitoring of nutritional status; nutrition and food hygiene education; household food security.” (OECD website, “Purpose Codes: sector classification” and “2012 CRS purpose codes_excel EN”).

According the guidance given by SUN, 100% of the funds assigned to a “nutrition-specific” activity will be counted toward the total (no weighting applied).

Nutrition-Sensitive Activities

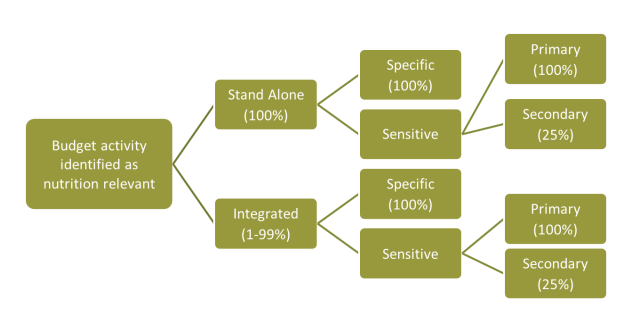

The SUN financial tracking guidance outlines its approach for identifying and weighting nutritionsensitive activities from the DAC. SPRING modified this guidance to align with the UNAP and to be relevant for both government and donor funding. These modifications have added one additional step (2). The overall approach and SPRING’s modifications can be summarized by Figure 2.

Figure 2: SPRING’s Modified Validation Approach

Broken out, this can be explained as follows:

- Identify the pool of potentially nutrition-sensitive projects and budget line items: SUN suggests using a combination of DAC codes and a key word search on the CRS database for donor activities. The lists of DAC codes and key words are presented in Appendices 2 and 3. SPRING MODIFICATION: SPRING’s roster of potentially nutrition-sensitive activities is derived from the defined activities in the UNAP implementation matrix. While many areas overlap with the DAC descriptions, there is some divergence, and the level of detail is greater in the UNAP than in the DAC (see “defining nutrition activities” section above).

- Integrated or Stand Alone Activity: very often in government budgets, and sometimes in donor activities, nutrition-relevant activities are “integrated” into larger non-relevant activities. Therefore SPRING had to undertake this additional step to allow for counting of partial components of the larger line item. In validation interviews, or via reading of project documents, SPRING endeavored to find out what percentage of a line item is nutrition-relevant.

- Nutrition-Sensitive vs Specific: SUN suggests reviewing the projects selected in Step 1 by assessing individually each project document. The objectives, expected results, and indicators are examined to determine whether the project is nutrition-sensitive. SUN requires the activity to pass three criteria: 1) project must intend to improve nutrition for women, adolescent girls, or children; 2) project has a significant nutrition objective OR nutrition indicator(s) (see Appendix 3); and 3) project must contribute to explicit nutrition-sensitive outcomes (through activities, indicators, and results; see Appendix 1). SPRING MODIFICATION: SPRING modifies the list of nutrition-sensitive outcomes to match the UNAP activity outputs. If there is an activity on SUN’s list that is not in the UNAP, that activity would not be counted in SPRING’s budgeting, unless it is given as a nutrition activity in our interviews.2 For instance, in SUN’s list, improving access to education/school to adolescent girls is not a UNAP activity, so a project with that as its only nutrition-sensitive outcome would not be counted in SPRING’s budgeting. A school feeding program would be counted however, as that is a UNAP activity

- For Nutrition-Sensitive, is it “Dominant” or “Partial”: Through the same review of project documents, classify the “intensity” of nutrition-sensitivity into two sub-categories: nutritionsensitive dominant or nutrition-sensitive partial. SPRING MODIFICATION: If no other information for a project is available, SPRING will use SUN’s weighting scheme (100 percent of funding is counted if a project’s main objective, results, outcomes, and indicators are nutritionsensitive; 25 percent if secondary objective, results, outcomes, and indicators are nutritionsensitive). However, SPRING has access to work plans or donor budgets and if there is insufficient information in these document to determine the approximate percent, SPRING will ask stakeholders to define breakdown for accounting. If SPRING still cannot define percent after these consultations, the SUN weighting scheme be applied. Documentation of our decisions will be made for each activity.

District Level

District-Level Considerations

At district level, nutrition budgets are integrated into broader, layered budgets. For this and a variety of other reasons, district planners may have a more difficult time approximating percentages. Thus, a modified methodology is required to: a) identify budget lines that relate to nutrition activities; and b) estimate the amounts dedicated to nutrition.

For each sector, relevant budget lines are identified through key informant interviews. In the baseline round, district officials were asked to identify nutrition-relevant activities, substantiate their activities by providing examples and relating the budget line to UNAP strategic areas, and asked to estimate how much funding was reserved for the nutrition activity.

SPRING/DSW developed with district stakeholders to transfer narrative into quantitative data. For example, when a key informant was asked to quantify “little,” or “most,” for activities related to nutrition, the SPRING/DSW team compiled responses and came up with the methodology to translate these words to a range of percentages. The midpoint of each range was used as the percentage in the calculations.

Based on this grassroots methodology, estimating nutrition shares of district budget lines were as follows:

- NO activity= 0%

- Little activity=10%

- Moderate= 50%

- Many activities=70%

- Most of the activities=80%

- All activities=100%

Further attempts to rationalize this scale to a more standard breakdown of percentages will be made in the future, but it depends on the understanding of the key informants.

CSO District-Level Budgets

Many CSOs were reluctant to give detailed project work plans and budgets to SPRING/DSW. Therefore, a short questionnaire (see Appendix 5) was developed to provide summarized budgets and project information for a given CSO.

Data Validation Process

SPRING is taking a two-pronged approach to ensure high-data quality. First, within our team, the following steps are taken in order to ensure inter-rater reliability:

- Regular group extraction meetings

- Feedback on ambiguous terms to OPM and NPA for guidance

- Notation and documentation in extraction sheets

- Cross-referencing figures from multiple sources, where available

Once extraction is completed, SPRING confirms the validity of the extracted ministry and donor budget data through meetings with the key informants for that ministry or donor. Every effort is made to crossvalidate data with the sector focal point seconded to the MOF. Any projects or activities that cannot be validated by the country or global team (donors) or line ministry and OPM (government) will be dropped from the analysis. Any unlisted projects named by the key informants will require supplemental documentation in order to be added to the analysis.

Exchange Rates

MOF reports off-budget donor funding in current-year USD. However, all ministry budget data is reported in current-year USH. SPRING is reporting final estimates in both USD and USH. Inter-bank exchange rates from the Ugandan Central Bank will be used for the conversions, averaged over the first month of the fiscal year.

Deflation/Inflation Rates and Base Year

National level analysis will begin at 2013/2014. For yearly reporting, no modifications are made to the reported figures in USD but for aggregated reporting of more than one year or reporting trends, SPRING uses 2013/2014 as the base year and succeeding years are adjusted to base-year dollars. Inflation rates are averaged over the fiscal year using the World Bank GDP-Deflator/Ugandan Bureau of Statistics Producer Price Index.

Limitations

Missing Data and Non-Response

The MOF document detailing off-budget support is released up to two fiscal years late, so these data have all had to be validated by donor sources. Given the large number of donors with at least one project, however, only the most active were contacted for in-depth data validation, while the others were contacted via email. For those projects not included in the MOF list, some respondents were not able to break down overall project budgets to yearly ones. When respondents could not provide this data during interviews, SPRING imputed the missing data from the total project commitment figure divided by the number of project years. This applies primarily to off-budget donor figures.

Data Quality

Most respondents to SPRING’s requests for information were unaware of the budget analysis methodology in the first round of data collection, which complicated efforts to appropriately identify and categorize relevant funds. Where possible, this challenge was overcome by capacity development of these respondents, who were better able to answer requests during the second round of data collection. However, the novelty of the categorization scheme for new staff and remaining difficulties in accessing complete data means that some funding estimates are reported as ranges or intervals, rather than exact numbers. This limitation can be overcome with continued capacity development, but does not preclude the dissemination of final results that include confidence intervals when necessary.

Changes over Time

SPRING is comparing data over several budget cycles, so it is important to use the same standards each round for comparability. However, as ministries become more aware of nutrition and “nutrition-sensitive” activities via the roll out of the UNAP, their accounting for activities may change and a greater number of activities may be identified as nutrition-sensitive, even if they existed in previous budgets. SPRING is making every effort to return to previous years’ data after each new round to check that “new” activities are indeed new and not just re-categorized.

Subjectivity of “Sensitive”

Defining "nutrition-sensitive" can be complicated. Within the data analysis team, SPRING ensures interrater reliability through regular group extraction meetings to discuss ambiguous activities listed in UNAP and cross-verifies final lists with the source ministry or donor organization.

Evolution of Nutrition Designation

Changes in the designation of nutrition-sensitive categories at the global and national levels are likely. The UNAP is not expected to change until 2017, but modifications—particularly related to water and sanitation (the Water and Environment Ministry was excluded from the original plan)—could be made. In response to a request from the OPM, SPRING included the Ministry of Water and Environment (MWE) in data collection efforts. While not a signatory ministry, the MWE’s role in UNAP rollout has been growing, and national stakeholders felt that not including these figures would not accurately reflect the level of investment in nutrition.

Footnotes

1 The World Bank and Government of Uganda have implemented PETS surveys in the education sector (1996-2001) and agriculture sector (2010).

2 Government considerations: When analyzing government work plans and budgets, one will notice that activities are not as explicitly defined, and few will have explicitly named results or indicators. This makes following the DAC guidance more difficult. SPRING endeavored to apply the same standards to both donor and government funding, but had to relax the set of three to become a set of the first and third criteria, with the second as an optional criterion if information is available. SPRING will discuss the extracted activities with each ministry to ensure the project has been appropriately defined as a nutrition-sensitive activity.

References

Government of Uganda. 2011. “Uganda Nutrition Action Plan 2011-2016: Scaling Up Multi-Sectoral Efforts to Establish a Strong Nutrition Foundation for Uganda’s Development.”

Lancet, The. 2013. “Executive Summary of The Lancet Maternal and Child Nutrition Series.” The Lancet Global Health 382 (9890).

Mucha, Noreen. 2012. “Implementing Nutrition-Sensitive Development: Reaching Consensus”. Bread for the World.

Sizomu, Anne Alan, Matthias Brucker, and Moses Muwonge. 2014. Family Planning in Uganda: A Review of National and District Policies and Budgets. Kampala, Uganda: DSW.

SUN Donor Network. 2013. “Methodology and Guidance Note to Track Global Investments in Nutrition” (PDF, 482 KB). Scaling Up Nutrition.

The International Budget Project. 2001. A Guide to Budget Work for NGOs. Washington, D.C.: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. www.internationalbudget.org.

USAID. 2014. “Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy 2014-2025.” (PDF, 1.3 MB)