"Pathways to Better Nutrition" Study

Summary of District Findings

PBN District Activities

As part of the national Pathways to Better Nutrition (PBN) study in Nepal (2014–2016), SPRING selected three “case” districts out of the original six Multi-sectoral Nutrition Plan (MSNP) prototype districts.1 In these three districts (Achham, Kapilvastu, and Parsa) and in three village development committees (VDCs), we used in–depth qualitative data as well as secondary survey and budget data to analyze how nutrition prioritization influences funding for nutrition near the end (January to April 2015) of the 2015/16 work-planning cycle.

Methods

Secondary Survey Data (“Snapshots of Nutrition”)

SPRING requested district data from respective district offices, health and other ministry management information systems (MIS), and the United Nations Field Coordination Office. We also compiled data from publicly available reports, such as the District and VDC Profile of Nepal, Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition, and others.

Using descriptive analysis (weighted, as needed), we created “snapshots” of nutrition for each district to highlight the status of key MSNP target indicators and of indicators representative of the eight MSNP output areas.

Qualitative Data

SPRING conducted key informant interviews in each district (and in one VDC in each district) across five of the six key stakeholder groups (donors, civil society, government, private sector, UN groups). A total of 55 interviews were conducted in the districts and 30 in the VDCs. We transcribed the data, then analyzed it in Nvivo, using objective “coding” to follow the themes of nutrition prioritization and funding.

SPRING staff coordinated final data validation meetings in these three districts in early 2016 to collect feedback on the results and gauge whether the situation changed since the interviews.

Budget Data

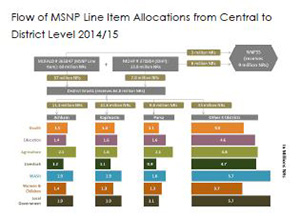

Although SPRING explored all nutrition-related funding at the national level, we collected district budget data only for the MSNP line item funding. We pulled data from the Red Book, MSNP budget summary 2014/15, and individual district budget documents for 2015/16, breaking down proposed and final allocations by district and sector.

Findings

Snapshots of Nutrition

Table 1. Summary of Key Indicators for Achham District

All three districts had higher underweight prevalence than the national average (29 percent); Parsa was the only district with higher than average stunting rates (52 percent). All three districts will need to make double-digit improvements in nearly all of their child nutrition indicators to meet the 2017 MSNP targets.

| Key Indicator | Level in Achham District | MSNP National Target (2017) |

|---|---|---|

| Completion of Primary Education2 | 49.36% | (Increased) |

| Stunting, Children Under 5 Years3 | 51.7% | 29% |

| Underweight, Children Under 5 Years3 | 36% | 20% |

| Wasting, Children Under 5 Years3 | 10.7% | 5% |

Achham and Parsa appeared to perform better than average on indicators relating to MSNP Output 5, while Kapilvastu outperformed the other two districts on MSNP Output 6. [See the District Snapshots for further analysis]

Qualitative Results

- Understanding of the MSNP was good among district stakeholders. More should be done to improve understanding of the MSNP among all nutrition and food security committee members at the VDC level.

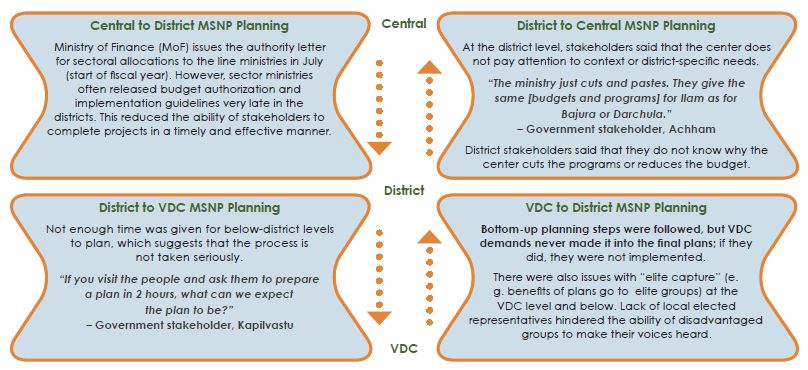

- MSNP has contributed to improved coordination among sectors at the district level, but human resources remained a problem in Parsa and Achham. Bottom-up planning had not yet been fully implemented, but some bottom-up planning was done for the MSNP line item.

- MSNP has contributed to improved perceptions and behaviors of government, donor, and UN groups related to prioritization of nutrition. All stakeholders agreed that prioritization for nutrition has increased in their work.

Budget Results

After the successful institution of an MSNP budget heading in the 2014/15 Red Book, the six MSNP prototype districts received these funds by April 2015. Delays were due to competing priorities within the sector ministry. This delay was reduced significantly in 2015/16.

A comparison of proposed vs. approved district work plans for these three districts revealed a divergence in the activities actually funded. A review of proposed 2015/16 MSNP funding shows increases in funding for Achham and Kapilvastu, but not for Parsa.

Conclusions

The MNSP was well understood and rolled out in these three districts, but further work needs to be done to increase understanding at the VDC level. There is also a need to strengthen the bottom-up process. A sandwich approach works best – the top should exercise authority and give overall direction, but be transparent and take input from the district level and below. There remained an emphasis on physical infrastructure projects in the VDCs and districts, with less attention given to topics like nutrition. Where nutrition was programmed, budget delays reduced the implementation period to 3-4 months, reducing the ability of stakeholders to complete projects in a timely and effective manner.

Much discussed at every level of data collection was the Nepali bottom-up planning process, defined by the Local Self Governance Act of 1999. The following schematic depicts the bottlenecks that occurred in this process during the time of our interviews.

Recommendations

- Address human resource constraints:

- Incentivize staff to work in far-flung VDCs.

- Reduce staff transfers and ensure that there are institutional mechanisms for transfer of knowledge when new staff members join.

- Consider a separate position for a joint district-and-VDC level nutrition focal person with the responsibility to coordinate and monitor nutrition activities.

- District and Village Nutrition and Food Security Steering Committees are excellent forums for all stakeholders. Work with these committees to plan, budget, share, and monitor nutrition data, and generate evidence-based programming.

- Spread out committee memberships so that the same people at the VDC level are not overburdened.

- Build understanding for multi-sectoral nutrition and nutrition-sensitivity among non-health government stakeholders

- Conduct bottom-up planning processes seriously so that community needs are taken into account in programs and the VDC stakeholders take greater ownership of the MSNP.

- Continue the investment in nutrition awareness and education through multiple channels: radio, TV, and print messages; and trainings and workshops.

- Sensitize opinion makers at the VDC level – political leaders, religious leaders, social workers – on nutrition issues to ensure that VDC-level planning and budgeting prioritizes nutrition.

- Reduce delays in release of funds to lower levels.

- External partners could introduce more flexibility into their programming to allow more context-specific activities.

Footnotes

1 Although these three districts are not representative of all 72 districts in Nepal, they represent half of the MSNP prototype districts and were selected for their diversity in terms of geographic location, nutritional status, and the predominant nutrition-related project within the district. We selected VDCs from the two MSNP VDCs in each district.

2 Intensive Study and Research Center (2014)

3 CBS, NPC, WFP, UNICEF and The World Bank (2014)