According to the 2013 Global Burden of Disease study, diet and nutrition-related factors represent the greatest risk factors for disease worldwide. The scope of malnutrition is enormous; billions of people are affected worldwide and it is estimated to cost the global economy 3.5 trillion U.S. dollars per year ($500 per person) (FAO 2013). Countries with a significant burden of overweight and obesity in addition to undernutrition are often said to face a “dual burden” of malnutrition. Figure 1 shows the scope of the dual burden of malnutrition globally. Working in nutrition today means, therefore, that one must understand interactions across the full spectrum of malnutrition and the impact these have on nutrition-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes and heart disease.

Malnutrition and nutrition-related NCDs are often interlinked and bound to food insecurity. Food insecurity not only causes hunger but may also interfere with healthy metabolic processes and can force individuals to eat low-quality foods, “feasting” when food is available to make up for periods of “famine” (Darnton-Hill and Coyne 1998; Dhurandhar 2016).

Unless policy makers apply the brakes on overweight, obesity and related disease and accelerate efforts to reduce undernutrition, everyone will pay a heavy price: death, disease, economic losses and degradation of the environment.

-Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition 2016

Coordinated policy action to address malnutrition, nutrition-related NCDs, and food security is critical. In the last decade, national policies and strategies for undernutrition have multiplied, but they rarely cover the full range of malnutrition. A World Health Organization (WHO) 2013 review found that most policies “do not adequately respond to the challenges that countries are facing today; in particular, the double burden of nutrition.” Separate from the national nutrition policies, there has been growth in multi-sectoral NCD-prevention policies in response to the 2011 Global Political Declaration on NCDs and to the rising prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.

Food security policy guidance can be embedded within agriculture or nutrition policies, or defined in stand-alone policies. Regardless of the format, national food security policy language often focuses on three primary issues: agricultural productivity, trade, and macro-economic policies (IUCN 2013). Although food security policy has become more inclusive of nutritional security over the last 20 years, few policies address how agriculture can reduce NCD risk.

With the call for multi-sectoral coordination that has come with the Sustainable Development Goals, funding has not necessarily increased. Multi-sectoral policies and specific sectoral policies must therefore focus on better harmonization for the efficient and effective use of resources.

In response to the growing dual burden, in 2017 the WHO identified a set of “double-duty actions” that affect many types of malnutrition, in essence increasing their value as an investment across nutrition, NCD, and food security platforms (WHO 2017). Including these and other double-duty actions across sectoral policies is one way to increase the likelihood of them being planned and funded (Pomeroy-Stevens, Viland, and Lamstein 2017).

What are Double-Duty Actions?

As defined by the WHO, double-duty actions include “interventions, programmes and policies that have the potential to simultaneously reduce the risk or burden of both undernutrition (including wasting, stunting and micronutrient deficiency or insufficiency) and overweight, obesity or diet-related NCDs (including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and some cancers)” (WHO 2017).

Policy Review Methods

SPRING examined the state of existing policies on double-duty actions in 29 countries. The countries selected were those listed as high priority for maternal and child health (MCH) and nutrition by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in 2017. Using a systematic Internet search and email requests to government representatives in each country, SPRING looked at their policy documents for nutrition, NCD prevention, and food security (if available). The searches were crosschecked with the WHO Global Database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action (GINA), SUN Movement country pages, and the Food & Agriculture Policy Decision Analysis Tool to determine if new plans were in process but had not been released. The search was conducted in Spanish and French as well. Documents reviewed included plans, policies, and strategies that outlined a strategic direction for the country. We did not review operational guidelines or protocols.

After locating the relevant policy documents, SPRING reviewed the objectives, outcomes, and activities listed in each to determine if they related to any of the six aforementioned double-duty actions identified by the WHO (2017):

- protections and promotion of exclusive breastfeeding

- actions to optimize early nutrition

- maternal nutrition

- antenatal care programs

- school food policies and programs

- marketing regulations

We also noted any other actions that could potentially be considered double-duty that were included in the policies. All references to double- duty actions were cross-referenced to identify any conflicting guidance. We did not include policies still under development, or those not yet launched (we note these draft policies in the detailed tables, but do not count them in the tallies).

Of the 29 countries in the initial search, SPRING selected eight with current active policies in all three areas (nutrition, NCD prevention, and food security) for a desk review, supplemented by phone calls and emails to government and nongovernmental organizations in each country. The results were compiled in an Excel database and a side-by-side comparison of the results was conducted to understand if and/or how double- duty actions were referenced in each document. We supplemented these findings with secondary data from the WHO Nutrition Global Targets Tracking Tool, the WHO data repository, and the Scaling Up Nutrition Movement Nutrition Budget Analysis Database.

Summary of Findings

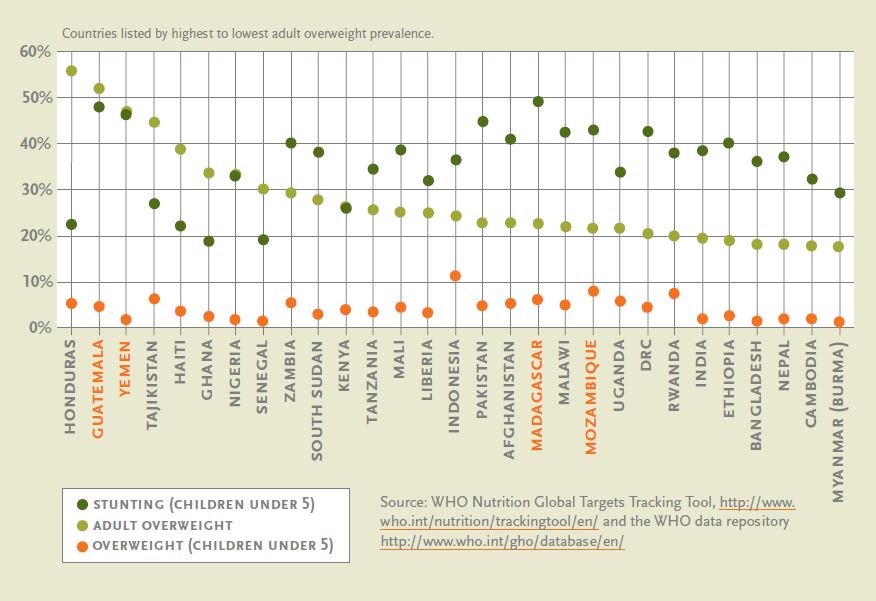

The 29 USAID MCH and nutrition priority countries account for about 20 percent of the total burden of global malnutrition. Based on the WHO nutrition target data and the WHO data repository, the average population-adjusted stunting rate for these countries is 38 percent and average rate of adult overweight is 22 percent. Madagascar, at 49.2 percent, has the highest rate of stunting, while Indonesia has the highest percentage of overweight children, at 11.5 percent. Guatemala has the highest rate (52 percent) of overweight in women of reproductive age. Several countries’ burdens of stunting and some form of overweight were among the top quintile among this group, signaling a clear dual burden (those highlighted).

The policy review provided several new insights. First, it revealed that there are few places to find comprehensive listings of national policies related to nutrition, NCDs, and food security. The WHO’s GINA database is well-designed and positioned to be a global repository, but most country listings have not been updated and, thus, GINA does not house current country policies: only two of the 29 countries reviewed had what appeared to be the latest policies for all three areas included in GINA. In addition, national ministry or secretariat websites often did not post the current policies, especially for food security.

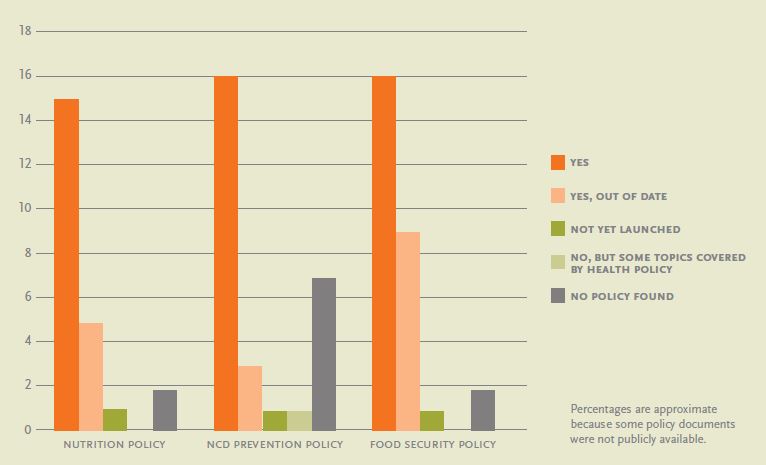

Second, overall there was limited availability of nutrition, NCD, and food security policies:

- 8 countries (28%) had all three policies.

- 10 countries (34%) had all three, but one or more were no longer in effect (end date had passed and no new policy had been launched).

- 8 countries (28%) had two of the three policies.

- 2 countries (7%), Democratic Republic of Congo and Haiti, had only one of three policy areas covered; one country (3%), South Sudan, had none.

Figure 3 shows the overall breakdown by policy area. Across these 29 countries, 7 had either already combined their nutrition and food security policies into one policy or were in the process of doing so. Only Tajikistan had a combined nutrition and NCD-prevention policy, in the form of its 2014 Nutrition and Physical Activity Strategy.

The in-depth policy review, limited to the eight countries that had all three policies, revealed that the dual burden was mentioned in nearly all nutrition and NCD policies, but rarely noted within food security policies. Among these countries, none identified all six WHO double- duty actions in all three policies.

Figure 3: Types of Policies Available for the 29 USAID Priority Countries

Table 1: Content Analysis of Nutrition, NCD, and Food Security Policies for Selected Countries

| Promotion of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) | Promotion of appropriate early & complementary feeding | Maternal nutrition— (IFA, MMS, and/or BPE) | Maternal antenatal care (ANC) | School feeding programs | Marketing regulations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cambodia | N, FS | N, FS | N, FS | N, FS | NCD | NCD |

| Guatemala | N, NCD | N, NCD | N, NCD | N, NCD | None | None |

| India | N, NCD, FS | N, FS | N | N, FS | N, NCD, FS | NCD |

| Madagascar | N | N | N | N | N | N, NCD |

| Nepal | N, NCD | N, NCD, FS | N | NCD | N, NCD, FS | NCD |

| Nigeria | N | N | N | N | N, FS | N, FS |

| Rwanda | N, FS | N, FS | N, FS | N, FS | N, FS | N, FS |

| Tanzania | N, NCD | N | N | N | N | N, NCD |

| N=nutrition; NCD=non-communicable disease; FS=food security | ||||||

To summarize across the eight countries we found that—

- activities to promote and support exclusive breastfeeding were included in 100% of the nutrition policies, 38% of the food security policies, and 50% of the NCD-prevention policies

- activities related to promotion of appropriate early and complementary feeding were included in 100% of the nutrition policies, 50% of the food security policies, and 25% of the NCD-prevention policies

- maternal nutrition interventions (defined here as supplementation of iron–folic acid, multiple micronutrient supplementation, and/ or balanced protein energy) were included in 100% of the nutrition policies, 25% of the food security policies, and 13% of the NCDprevention policies

- maternal antenatal care was included in 100% of the nutrition policies, 38% of the food security policies, and 25% of the NCDprevention policies

- school feeding programs were included in 75% of the nutrition policies, 50% of the food security policies, and 38% of the NCDprevention policies

- marketing regulations were included in 50% of the nutrition policies, 25% of the food security policies, and 63% of the NCD-prevention policies.

Unsurprisingly, Cambodia and Rwanda, which had joint nutrition and food security policies, mentioned double-duty actions more and with fewer conflicts in guidance. Unfortunately, in their NCD policies, both countries had very low inclusion of double-duty actions. Across the eight countries, NCD policies typically focused on marketing regulations, school feeding, and exclusive breastfeeding, while food security policies usually focused on school feeding and some component of infant and young child feeding, if mentioned at all.

In addition to the WHO-suggested double-duty actions, the review identified several actions across policies that have the potential to also be counted as “double duty” actions (depending on how they are implemented), such as—

- diversifying food production for micronutrient-rich foods

- improving NCD integration with other health programs

- educating the community about nutrition and healthy eating

- promoting home and school gardens

- Offering adolescent girls’ nutrition education, including life skills and delaying pregnancy

- improving nutritional labeling.

- developing effective fruit and vegetable value chains

- developing urban agriculture strategies

- holding joint screening programs for malnutrition and NCD risk factors in schools

- reducing aflatoxin (Rwanda notes aflatoxin specifically in its NCD policy “as a cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma”).

Many of these potential actions fall within the area of agriculture and food security; further evidence is needed to determine the impact they might have on all forms of malnutrition.

Regarding conflicting guidance across policies, seven of the eight countries had at least one potential conflict in the guidance given for a double-duty action across two or more policies. Most often this came up in the treatment of salt as a “friend” (iodization) or “foe” (taxation to reduce consumption), which could complicate national marketing regulations for salt. There were also multiple conflicts related to regulation and implementation of school feeding programs and nutrition education, which could impact the scale, quality, and nutrition-sensitivity of these programs. Finally, only two countries specifically mention the need to coordinate across multi-sector policy platforms.

Limitations

Since the concept of double-duty actions is still emerging, the results of this review should not be considered a critique but rather a way to assess the attention given to these actions. The following are some limitations of this study:

- In some cases, we may have missed late-breaking developments or documents that were not publicly available at the time of review.

- This policy review reflects only what is written in the policy documents, which may or may not reflect what activities are planned, funded, and implemented in each sector.

- We did not search for addendums, revisions, riders, or other edits to the policies, as launched. This may mean we missed some changes to the language, the stated objectives, and/or the planned activities relating to the dual burden.

Recommendations

Recognizing these limitations, our findings should be helpful in determining how to improve the harmonization of policy and increase the prioritization of double-duty actions. This review should encourage discussion about how to maximize investments across the malnutrition spectrum.

We offer these recommendations to country government staff working in the areas of nutrition, NCD prevention and food security as they review and revise their own policies:

- Consider merging or connecting the many multi-sectoral committees called for across these plans.

- Ensure that all three policy areas reference the full spectrum of malnutrition and how they are working to reduce that burden.

- Use databases such as GINA or a national inter-sectoral mechanism to provide transparency on current policies in each area.

- Increase discussions on how to test integration of nutrition, NCD, and food insecurity strategies for education campaigns, screening, and care.

- Increase evidence-generation on food and agriculture-based actions to reduce the dual burden.

- Track the funding allocated to double-duty actions across sectors. This information can be used for accounting, advocacy, and monitoring.

References

Darnton-Hill, I., and E. T. Coyne. 1998. “Feast and Famine: Socioeconomic Disparities in Global Nutrition and Health.” Public Health Nutrition 1 (1): 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1079/ PHN19980005.

Dhurandhar, Emily J. 2016. “The Food-Insecurity Obesity Paradox: A Resource Scarcity Hypothesis.” Physiology & Behavior 162 (August): 88–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. physbeh.2016.04.025.

FAO. 2013. “State of Food and Agriculture 2013: Food Systems for Better Nutrition.” Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Forouzanfar, Mohammad H., et al. 2013. “Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.” The Lancet, Volume 386, Issue 10010, 2287 - 2323, doi: 10.1016/ S0140– 6736(15)00128-2.

IUCN. 2013. “Food Security Policies: Making the Ecosystem Connections.” Gland: Switzerland: International Union For Conservation of Nature.

Pomeroy-Stevens, Amanda, Heather Viland, and Sascha Lamstein. 2017. “Recommendations for Multi-Sector Nutrition Planning: Cross- Context Lessons from Nepal and Uganda.” ENN Field Exchange, no. 54 (February): 90–94.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2017. “Double-Duty Actions for Nutrition. Policy Brief.” Geneva: Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO).WHO (World Health Organization). 2018. WHO Nutrition Global Targets Tracking Tool at http://www.who.int/ nutrition/trackingtool/en/ and the WHO Data Repository at http://www.who.int/gho/ database/en/.