Using Budget and Expenditure Data to Accelerate Progress on Nutrition

Nutrition budget and expenditure analysis determines how much has been allocated for nutrition over time, by various sources, and at the national and sub-national level. The USAID-funded SPRING Project has gathered and synthesized information from 11 countries on how they have used findings from their budget analysis activities.

Malnutrition has severe health and economic consequences. It is responsible for roughly half of all deaths among children around the world, and contributes significantly to the global burden of disease. Malnutrition impedes growth and development, depriving individuals and communities of their full potential, and draining national economic productivity. Many actors have come together under the auspices of the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement, the Millennium and Sustainable Development Goals (MDGs and SDGs), and other frameworks to confront this problem, but achieving results will require adequate funding. Estimates from the World Bank’s Investing in Nutrition report suggest that the global community is seven billion dollars short of the funding necessary to effectively address the issue of malnutrition.

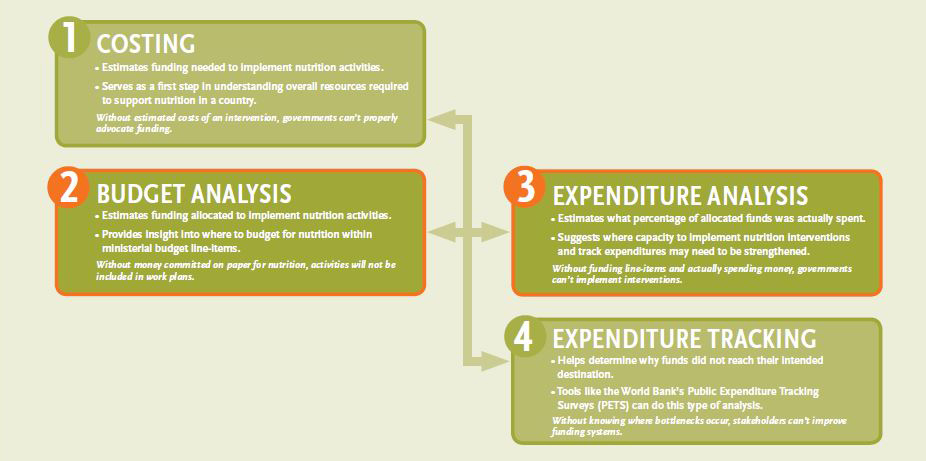

Until very recently, few nutrition actors were able to say how much funding was allocated to nutrition. The lack of data on national nutrition budgets and spending meant that governments and implementing partners did not have accurate, up-to-date information on how nutrition was being prioritized or how well countries were spending their nutrition funds. Conducting a nutrition budget analysis is one way to start answering these questions (Figure 1).

By the end of 2017, nearly 50 countries had analyzed how much money had been budgeted for (or allocated to) nutrition (step 2 in Figure 1). Many of these countries used have used guidance from the SUN Movement, as well as other tools, including SPRING’s Nutrition Budget Analysis Tool. These efforts are still evolving; SUN, along with several donor -funded nutrition projects, have released guidance to help countries collect budget data and make an investment case (see Budget analysis for nutrition: A guidance note for countries [update 2017]). A few countries have also gone one step further, tracking actual nutrition spending (expenditures, step 3 in Figure 1), which are often quite different from what was budgeted.

By the end of 2017, 47 countries had analyzed the funding allocated to nutrition in their government budgets.

Once countries have collected data on nutrition allocations and/or spending, they can use the results to improve decision making for nutrition. SPRING gathered information and interviewed 25 key decision-makers in 11 countries—from ministry staff to local nongovernmental agencies—to learn more about country-level experiences using budget data for decision making. We synthesized these experiences to explore how these countries used budget data to foster meaningful changes in their policies and funding. We addressed three questions:

- How are findings from nutrition budget analysis activities being used?

- What lessons have countries learned about using nutrition budget analysis data?

- How can we improve use of nutrition budget data?

Figure 1: What is Nutrition Budget and Expenditure Analysis?

How Are Findings from Nutrition Budget And Expenditure Analysis Used?

From our interviews and review of the literature, we identified three complementary ways in which findings from nutrition budget and expenditure analysis have been used.

Conducting the analysis is one way of bringing together information from multiple sectors and stakeholders, especially in countries where nutrition activities are fragmented across different agencies and departments. Some countries may include funding for nutrition activities in multiple ministries, often with multiple donors. The analysis may also include nutrition activities funded at the regional or local level that are not included in national ministry budgets. Findings from our review showed that the simple act of mapping and connecting nutrition actors and activities while conducting the analysis is helpful for developing coordination structures that incorporate a broad range of stakeholders. By following the flow of funding, budget analysis can identify stakeholders who may not traditionally be thought of as having an interest in nutrition. Working together to collect, analyze, and review budget information can provide a harmonized way of bringing relevant stakeholders to the table.

We found many new nutrition stakeholders in the multi-sector framework. That is where we found out that there are NGOs that not only participate in nutrition, but also food security and social protection.

-Stakeholder from the Democratic Republic of Congo

In Tanzania, the Prime Minister’s office led a public expenditure review (PER) in 2014, which identified patterns of nutrition expenditure across different line ministries. The process of data collection was difficult, but it helped stakeholders have the important discussion of what ‘nutrition’ was, identify key nutrition stakeholders, and identify and coordinate with nutritionsensitive CSOs and Donors who had not previously been engaged.

Sharing findings was useful in building relationships [with other sectors] to inform and build the NNP [National Nutrition Policy].

-Stakeholder from Tanzania

Papua New Guinea conducted its first budget analysis in 2016 and used that experience, as well as their participation in SUN-led workshops on nutrition budgeting, to identify nutrition activities that already exist within the Public Investment Program. An analysis of program gaps resulted in the addition of water and sanitation WASH stakeholders into the nutrition conversation.

The good thing is that we agreed with the country on a list of activities that we consider nutrition spending. We might disagree on some of the activities listed but at the end of the day it is the country’s decision to decide what they consider nutrition investments.

-Stakeholder from Côte d’Ivoire

One round of budget and/or expenditure analysis may not be enough to identify all nutrition actors or programs. It may take a few iterations in order to identify all the nutrition activities taking place and the gaps in nutrition programming. For example, the Philippines, Côte d’Ivoire and Tanzania started by tracking nutrition spending by the government's health sector.

In the future, budget analyses will focus more on nutrition-specific programs because it is more straightforward.

-Stakeholder from the Philippines

Making the case for increased funding requires that countries identify gaps in nutrition programming, understand the barriers to filling these gaps, and call on stakeholders to take responsibility for the solutions. Because nutrition is a multisectoral issue, it can get lost among other national priorities. A clear and sustained advocacy campaign with a well-stated case for investment must target the decision makers (including the Ministry of Finance) who have power over budgets and spending.

Budget analysis can highlight funding gaps and shortfalls in financial commitments by comparing budget data against identified nutrition programming needs, funding provided to other sectors, or the costs of not addressing nutrition at all. Findings from nutrition budget and expenditure analysis can be compared with the amount being lost to poor nutrition, making a compelling case for increased funding for nutrition.

In our interviews, 7 out of 11 countries said that budget and/or expenditure data were useful for making an advocacy case for nutrition.

We had to see why we needed to invest in nutrition. The analysis we have completed shows that the investment needs are still immense.

-Stakeholder from Senegal

Using findings from budget and expenditure analysis to advocate additional funding is not always straightforward. Findings need to be tailored to specific decision makers and stakeholders, and the numbers need to be placed in context, for instance by comparing them to projected costs of an activity to show the investment gap, or by showing how much is spent per child or per mother. Repeating budget analysis yearly can be a compelling advocacy tool that shows increases or decreases in financial commitment. Timing of the release of this information is also key—it should align with key points in the budget process.

Madagascar took a multi-stakeholder approach to creating advocacy messages based on findings from the budget analysis activities: lobbying the Prime Minister resulted in a promise to increase the budget allocated to nutrition and to revise the medium-term expenditure framework (a primary document for dictating national spending). A parliamentary alliance was set up by the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) to advocate nutrition, and individual advocacy has targeted donors and external investors.

In Malawi, the civil society alliance for nutrition has been doing annual nutrition budget analysis since 2013, as part of a call to action for nutrition. They presented findings to members of parliament and other key stakeholders and compared them with national Nutrition for Growth commitments and Cost of Hunger data in order to make the investment case for nutrition. The result was that 15 members of parliament, including government finance staff were trained as “nutrition champions,” thereby increasing the number of trained nutrition champions in Malawi from 13 to approximately 35.

In Nepal, the civil society alliance there also worked to advocate subnationally:

We advocate these findings to the layers of people through a decentralized process, and engaged citizens through public hearings.

-Stakeholder from Nepal

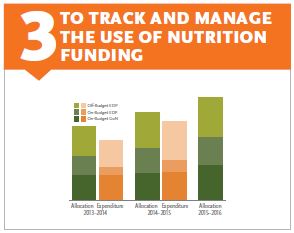

Some countries institute a routine reporting system to better manage funding for and expenditures on nutrition. This allows them to more transparently track resources, ensure that commitments are fulfilled, and verify that funding is used effectively. Setting up an annual reporting system can be onerous, as it requires the active participation of a variety of stakeholders, careful planning, compatible sector data systems, and a fair amount of trial-and-error.

Nutrition budget analysis has been completed in Madagascar almost every year since 2013. They found that in Malawi, a Nutrition Resource Tracking System (NURTS) has been developed to track governmental and donor funding on nutrition, which was introduced in 2016 and is still in the testing phase. Budget tracking committees have been set up in five districts to improve monitoring of funding at the district level.

[T]he analysis was beneficial because it measured the gap in nutrition budgeting and noted progressions. It revealed shortcomings linked to the ability to trace nutrition financing and the ability to control the analytical tools.

-Stakeholder from Madagascar

In Malawi, a Nutrition Resource Tracking System (NURTS) has been developed to track governmental and donor funding on nutrition, which was introduced in 2016 and is still in the testing phase. Budget tracking committees have been set up in five districts to improve monitoring of funding at the district level.

In Nepal, nutrition budget analysis was completed for the years 2013–2016 to track funding for the Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Plan 2013–2017 (MSNP I). The analysis showed the influence of the MSNP I on funding commitments, and identified opportunities to improve spending. The government is now discussing how to routinely track resources for nutrition, possibly through the use of nutrition budget codes.

Some countries have found it necessary to analyze additional information on nutrition programming in order to identify needs and priorities. For example, in Guatemala, the Secretariat for Food Security and Nutrition (SESAN) developed an integrated system for nutrition resource tracking, allowing for quarterly auditing of nutrition outputs (like number of counseling sessions or distributed RUTF) against nutrition spending (Victoria et al. 2016). These data have helped propel evidence-based decision making within the country’s Zero Hunger Plan.

What Lessons Have Countries Learned About Using Data from Nutrition Budget And Expenditure Analysis?

Nutrition budget and expenditure analysis is a new initiative in many countries, and the individuals we spoke with shared many lessons that they have learned in the early stages of this process. As country efforts adapt and evolve, more is being learned each year; we have summarized key lessons in Figure 2, described in greater detail below.

Figure 2: From Interviews and Observations, Spring Identified 6 Key Lessons

- There is no one “right way” to use the data from nutrition budget and expenditure analysis— data use should fit the country’s needs

- Financial analysis is often an iterative, evolving process, and the availability and use of data often improves with each subsequent round of analysis

- Knowing when to use your findings is an important part of the process

- Involving a range of stakeholders in budget analysis and dissemination broadens perspectives and increases buy-in and use of findings

- Target the dissemination of findings, using language and evidence appropriate for each appropriate audience

- Consider adopting systems to make monitoring and tracking routine

There is no one “right way” to use the data from nutrition budget and expenditure analysis—data use should fit the country’s needs.

We have highlighted three reasons for conducting budget analyses, but many other valid reasons exist. Countries may use findings from nutrition budget and expenditure analysis in very different ways depending on how policy is made, how budgets or expenditures are reported are finalized, the reasons for doing the analysis, and which stakeholders are involved.

Financial analysis is often an iterative, evolving process, and the availability and use of data often improves with each subsequent round of analysis.

Countries reported that even when one-time budget analysis findings were wellreceived by government decision makers, providing regular data would be more effective for changing policy and influencing budgets over the longer term. Nutrition budget and expenditure analysis should be a repeated effort with the expectation that data quality will improve over time. It is important to set appropriate expectations for stakeholders at each phase and plan a long-term approach and dissemination strategy. This does not have to mean that it is a yearly effort. For example, Tanzania plans to do the PER every couple of years. In Malawi, there is an effort to roll out a tracking system that would allow continued, ongoing collection and analysis of nutrition budget data.

Now that we have a strategic plan that incorporates specific and ‘sensitive’ interventions that are divided into different departments based on the activities of said interventions, we consider that we have a basis to move forward with. This basis will inform us as to what dollar amount needs to be invested over next five years for nutritional funding.

-Stakeholder from Senegal

As stakeholders change and the audience becomes more knowledgeable, so do the types of budget and expenditure analysis and the presentation of the findings. Stakeholder and policymaker feedback on results of the analysis can give them a better understanding of what is needed to change policies and plans. In Zambia, each round of analysis helped local governments and additional stakeholders engage at opportune moments.

We plan on making changes to the approach because the work that we did was at a national level. We discussed and agreed during the process that we were doing at the national level, that it would be interesting to do the resource tracking at the local level (region by region). I believe that for the decision-making process it will be more useful because the nutrition problem in the northeast region may be different from what is occurring in the south. Having this regional information by will be more useful for decision makers rather than having a big national overview.

-Stakeholder from Côte d’Ivoire

We will use our next [analysis] to see if we have moved forward and see how we can improve. This is a good tool to develop a convincing argument for improving nutrition through increasing money and efficiencies of resources.

-Stakeholder from Tanzania

The first exercise looked at what was in the government budget. The second can include additional sources.

-Stakeholder from Papua New Guinea

Knowing when to use your findings is an important part of the process.

For findings to be used effectively, analysis should be done with a strong understanding of the budget and planning cycle. Budget and expenditure analysis is most effective for planning and advocacy when it is timed so that the results can be shared with decision makers while the budgeting process is ongoing. In Tajikistan, the Ministry of Finance provided input about the appropriate times for nutrition advocates to get involved in the budgeting process.

Budget analysis is particularly powerful if completed in time for parliament’s discussion on the budget—a key advocacy moment. Parliamentarians can then use the figures from the analysis to ask questions of the minister and his or her senior civil servants. A higher quality debate may result.

-(Bagnall-Oakeley, 08/24/2016)

In Papua New Guinea, the Department of National Planning and Monitoring provided support to the analysis process, including recommending a rolled out approach to gradually increase funding for nutrition programming.

The annual nutrition budget for health is small. We need to use advocacy to get secretaries in other sectors to support nutrition.

-Stakeholder from Papua New Guinea

Involving a range of stakeholders in budget analysis and dissemination broadens perspectives and increases buy-in and use of findings.

In conducting and disseminating the analyses, countries identified implementers who were not previously considered part of the nutrition realm. Donors have become more interested in having their contributions to the national plans reflected in the analyses, even when those contributions come outside of the national budget. Although the budget analysis itself is often limited to a small group of stakeholders, sharing and discussing the findings offers a chance to involve a wide range of actors, defining a broader nutrition community.

Involving staff from the planning department, the ministry of finance, and the ministry of economics in the nutrition budget and/or expenditure analysis process can ensure that information is shared with the right stakeholders in time to affect their decision-making. Including the right people can help ensure that all of the dots are connected and that all of the data sources are used. In addition, governments can increase the reach of their findings on nutrition funding by involving civil society partners early in the process. Civil society can improve the depth and quality of their advocacy by using government data.

The nutrition secretariat in Madagascar has completed nutrition budget analysis, and also developed an investment case for nutrition in 2017 (with UNICEF) that outlines the costs to the country of not addressing malnutrition. However, the two sets of data do not appear have been compared or integrated to estimate the investment gap for nutrition (ONN and UNICEF 2017).

In Zambia, including off-budget, donor-funded activities has required coordination with and participation of the donor organizations during the analysis and dissemination process, creating further opportunities to engage these donors in coordination of nutrition funding.

Target the dissemination of findings, using language and evidence appropriate for each appropriate audience.

Initially, the goal of sharing analysis findings may simply be to raise awareness of the need for more detailed data about nutrition funding. The first analyses may reveal a need to strengthen or disaggregate existing resource tracking systems to allow for more accurate analyses in the future. This iterative process happened in the early days of global HIV/AIDS resource tracking, leading to improvements in resource tracking at the country level.

In Nepal, the nutrition budget analysis process has resulted in regular check-ins with the Ministry of Finance (MOF), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Local Development (MOFALD) and other relevant ministries.

In Zambia, the budget analysis process revealed a need to make reporting of the results more systematic. This resulted in the development of more frequent and detailed annual budget tracking reports, which informs stakeholders and the government whether they are meeting their commitments, and ensures that nutrition remains a priority.

In the Philippines, the goal was to work more closely with the Department of Budget Management to explicitly state how much funding was set aside for nutrition on specific activities in every program that was budgeted.

In Tajikistan, the budget analysis exercise made it clear that current systems do not allow for identification of nutrition activities in the budget, and make it difficult to understand how much international organizations are contributing to nutrition programming. As a result, the Ministry of Finance is in the process of investigating specific programs (such as the maternal and child/adolescent nutrition package) to develop a better understanding of the cost of vital programs to make a case for increased nutrition funding.

Budget analysis does not show the whole picture. An expenditure analysis would help to show if the budget is being used as planned.

-Stakeholder from Malawi

Consider adopting systems to make monitoring and tracking routine.

In most countries, budget analysis is done by reviewing and analyzing individual budgets from different departments and agencies. However, nutrition budget data can rarely be found within routine information or tracking systems. This slows the process and means that financial information cannot easily be linked to other routine nutrition monitoring data. Developing a system for nutrition resource tracking can greatly facilitate the process of reporting, collecting, analyzing, and using nutrition budget and expenditure data..

One of the major difficulties was access to financial data.

-Stakeholder from Senegal

In Peru, nutrition expenditure estimates are shared in a publicly available, electronic portal— Consulta Amigable—managed by the Ministry of Economy and Finance. These data also support regular promotion of the nutrition agenda at sub-national level (SUN Movement 2016).

How Can We Improve Use of Data from Nutrition Budget and Expenditure?

The experiences highlighted here suggest that analysis findings can be useful to decision makers and an effective tool for strengthening governance for nutrition. Budget and expenditure analysis can only affect funding allocations and expenditures for nutrition if the findings are used and convincingly shared with decision makers.

There is more work to do. Estimates of nutrition funding and expenditures can have wide margins of error, and often are not comparable to the estimated costs of activities. This makes it difficult to clearly define gaps in spending, which is needed to make a case for investing in nutrition (Pomeroy-Stevens et al. 2017). In addition, a lack of information on district-level budgets and expenditures makes it challenging to determine if funding and/or expenditures match local needs or translates into implementation. Nonetheless, these early estimates are a huge step forward in planning and advocating for nutrition funding, and provide essential building blocks for future analysis of planned and actual nutrition spending.

References

In addition to the references cited in this brief, please visit the “Investing in Nutrition” page on the SUN website for more detail on country experiences, as well as the SUN threestep process for conducting budget analysis. The SPRING website also provides tools and country experiences on nutrition budgeting and financial analysis.

Bagnall-Oakeley, Hugh. 08/24/2016. “Follow the Money: A Quick Intro to Budget Analysis.” Save the Children website. https:// blogs.savethechildren.org.uk/2016/08/follow- the-money-a-quick-introduction-to-budget- analysis/. August 24, 2016.

ONN, and UNICEF. 2017. “Madagascar Nutrition Investment Case.” Antananarivo, Madagascar: UNICEF. https://www.unicef. org/madagascar/eng/GRAND-RAPPORTPEN- ENG-64pages-10juillet2017-Web-version. pdf.

Pomeroy-Stevens, Amanda, Alexis D’Agostino, Madhukar B Shrestha, and Abel Muzoora. 2017. “A Multisector Approach to Monitoring Planned and Actual Nutrition Spending.” ENN Field Exchange, no. 55 (August):p49–52.

SUN Movement. 2016. “Lessons of Value from Guatemala and Peru Where the Sub-National Governments Play Varying Roles.” SUN in Practice, April. http://scalingupnutrition. org/news/using-results-fromthe- budget-analysis-to-track-on-budget-actual- expenditures-peru-and-guatemala/.

Victoria, Paula, Ariela Luna, Jose Velasquez, Rommy Rios, German Gonzalez, William Knechtel, Vagn Mikkelsen, and Patrizia Fracassi. 2016. “Panel 7.1: Guatemala and Peru: Timely Access to Financial Data Makes a Difference in Actual Spending and Spurs Accountability at All Levels.” In Global Nutrition Report 2016: From Promise to Impact: Ending Malnutrition by 2030, 83. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. http://ebrary.ifpri. org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/ id/130354/filename/130565.pdf.

http://www.scalingupnutrition.org/sharelearn/planning-and-implementation...