Introduction

Today, the world faces a double burden of malnutrition, with almost three billion people suffering from either undernutrition or overweight and obesity (FAO 2013). No country is untouched. Hunger and inadequate nutrition contribute to high rates of maternal, infant, and child anemia, morbidity, and mortality. They also result in impaired cognitive function and reduced future productivity, as well as the development of obesity and nutrition-related chronic conditions like diabetes.

The causes of this crisis are numerous. In 2014, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) released its Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy (2014–2025) recognizing the “multi-factorial causation” of malnutrition (USAID 2014a), and a local systems framework, Local Systems: A Framework for Supporting Sustained Development (USAID 2014b), which suggested that multi-sectoral approaches would benefit from using systems thinking to strengthen design, implementation, and measurement. Although there is growing enthusiasm for systems thinking, very little guidance exists on how a country can incorporate the approach into their program design and implementation.

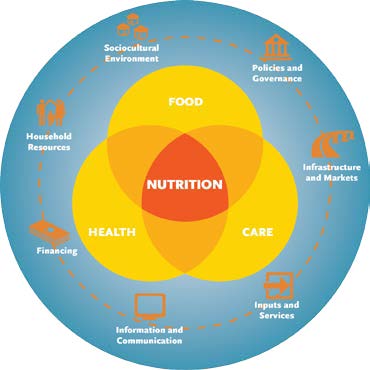

Figure 1. Framework for Systems Thinking and Action for Nutrition

In response, in 2015, USAID’s multi-sectoral nutrition project, SPRING, developed a simple framework for applying systems thinking (figure 1). This framework took inspiration from USAID’s paper on local systems (2014b), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) framework of the causes of undernutrition (UNICEF 1990, 2013), and the World Health Organization’s building blocks for health systems (WHO 2010). SPRING hypothesized that nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive programs, given the multi-sectoral nature of solutions to malnutrition, could benefit from a systems approach. We went further, hypothesizing that, in the absence of this type of an approach, programs may not adequately anticipate unintended consequences or strengthen existing systems to ensure sustainability and facilitate scale-up.

We developed this brief, which explores SPRING’s work in the Kyrgyz Republic, as well as a companion brief on our work in Ghana for designers and implementers of multi-sectoral nutrition programs like SPRING. Our goal was to determine how well the SPRING systems framework maps to “real world” nutrition programs. It is important to note that we did not deliberately apply systems thinking during program design or implementation in the Kyrgyz Republic because we had not yet developed the framework or related tools. This analysis is, therefore, a retrospective “test fit” to inform future programs.

By using the framework to guide this qualitative mapping exercise, we were able to identify areas that were successful as well as those that could be strengthened with a systems-thinking approach. In the sections that follow, we explore the extent to which each factor in the systems framework was considered and/or addressed as well as the attention given to feedback loops and unintended consequences. We end with a summary of our lessons learned regarding the systems framework.

To view the full text and annotations, please download the report above.