This brief is the first in a series of "interim" technical briefs, culminating in a final two-year study report in 2015. It focuses on findings from SPRING's baseline interviews with key national-level stakeholders in Uganda, presenting their perceptions and attitudes about the "scale-up" of nutrition programs in Uganda, including the multisectoral effort to roll out the Ugandan Nutrition Action Plan (UNAP) and the alignment with the global Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) movement within Uganda.

Before the findings from Uganda, including a description of the UNAP, this brief presents the background of the SUN Movement and Pathways to Better Nutrition (PBN) case studies.

Background

The SUN Movement

Several recent international movements have been pushing nutrition to the forefront of development priorities. Many have set ambitious targets or goals related to the reduction of undernutrition in children younger than five years and women of reproductive age.1,2,3,4 The SUN Movement, in particular, has gone beyond setting targets and has focused on supporting processes, policies, and systems for scaling up nutrition within countries. As an advocacy group based in the UN, SUN is intended to stimulate and reinforce political interest in nutrition among leaders of national governments and development partners. According to the UN Standing Committee on Nutrition, "Scaling Up Nutrition is a global push for action and investment to improve maternal and child nutrition." 5 The four key processes guiding SUN country engagement are: bring people together; put policies in place; implement and align programs; and mobilize resources.6

As of April 2014, 50 countries had joined the SUN movement. SUN is generally seen as a global leader for advancing the nutrition agenda and has produced guidance on key high-level processes, costing of plans, and technical guidance on the national plan development.

Uganda is a signatory to the SUN movement and other relevant agreements such as the MDGs and the World Food Summit. They have also adopted the African Regional Nutrition Strategy and the Comprehensive African Agriculture Development Programme of the African Union.

The PBN Case Studies

The USAID-funded SPRING project began implementation of the "Pathways to Better Nutrition" (PBN) case studies in 2013. The objective of these case studies is to explore how government prioritizes nutrition interventions and supports the implementation of its multisector national nutrition plan to reach its goals of reducing undernutrition.

In order to increase the odds of capturing an active period of nutrition activities, two countries from a pool of SUN signatory countries were chosen, which ensures that have signed on to reduce undernutrition and have an actionable national nutrition plan. In addition, they must pass the following criteria: a) be rated as "ready to scale up" or "already scaling up"; b) have a medium or strong nutrition governance rating by the WHO, and c) have partnership with donor(s) who provide sufficient financial support starting in FY 2013. Based on these criteria and in consultation with country nutrition coordinating bodies, SPRING has selected Uganda as the first study country. SPRING is also conducting a similar case study in Nepal.

In the process of answering the case study research questions (see website for full listing), SPRING is focusing on four key domains of inquiry:

- Learning, adaptation, and evidence on scale-up

- Adaptation of innovations/interventions to context(s)

- Financing of nutrition activities

- Planning for sustainability

In this technical brief, SPRING explores how "scaling up" is perceived in Uganda by stakeholders who are implementing nutrition programs through the UNAP.

Methods Summary

The data for this brief are from the first round of national data collection in Kampala, conducted in November 2013. Data were collected via key informant interviews, document collection, and direct observation of meetings. SPRING is continuing to explore study domains and pursue overall study questions through district-level data collection, follow-up data collection, and documentation of the UNAP coordination and planning meetings through 2015. Future technical briefs will use these along with follow-on data from both the national and district level to develop the themes discovered in the initial round of interviews.

SPRING is working closely with the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM). Key informants represent nutrition donors, UN organizations, six UNAP-related government ministries, civil society organizations (CSOs), and research and private sector organizations to ensure a balanced account of funding and activities.

For in-depth discussion of the methods used, see the Pathways to Better Nutrition Case Study Series page.

The Case of Uganda

Uganda's National Nutrition Plan

Over the last few decades, Uganda has made significant progress in planning for improved nutrition, as policymakers have recognized the importance of developing a strong multisectoral effort to combat malnutrition in the country. In consideration of their agreed-upon targets and goals with SUN and other international coordinating bodies and developed within the context of national policy and legal frameworks, the Ugandan government produced the 2011–2016 UNAP, which has set its own targets and goals for nutrition.

The UNAP builds on previous national and regional policies, most notably the National Development Plan, the Uganda Food and Nutrition Policy, and nutrition sections of the Health Sector Strategic and Investment Plan and the Agricultural Sector Development Strategy and Investment Plan.

The UNAP focuses on the 1,000 days period from conception to the child's second birthday. As described in the UNAP, Their framework comprehensively addresses five objectives (Government of Uganda 2011):

- Objective 1: Improve access to and utilization of maternal, infant, and young child feeding.

- Objective 2: Enhance consumption of diverse diets comprehensively addresses food availability, access, use and sustainability for improved nutrition.

- Objective 3: Protect households from the impact of shocks and other vulnerabilities that affect their nutritional status.

- Objective 4: Strengthen the policy, legal and institutional frameworks and the capacity to effectively plan, implement, monitor and evaluate nutrition programs.

A coordination body was to be created to oversee UNAP roll-out across sectors and non-ministerial partners. However, there were practical challenges to the formation of this committee, so the OPM was designated to be directly responsible for the coordination of the UNAP. The UNAP Implementation Secretariat is in the Department of Policy Implementation and Coordination at OPM.

Familiarity with and Perceptions of the SUN Movement

Prior to discussing the idea of "scale-up" in Uganda, respondents were asked about their familiarity with the eponymous movement. While the majority of stakeholders were familiar with it, fewer had insight into how SUN worked with OPM, if it would be involved in the roll-out of UNAP, and what differences there were between the SUN mandate and the UNAP's goals.

While not unanimous, a majority of stakeholders noted that SUN was a positive development on the global level for advocating for nutrition but that Uganda was already on track to develop the UNAP before SUN came along, so its influence on Uganda was not groundbreaking. Several people noted that the focus on the 1,000 days period, however, was a SUN contribution.

The global movement is trying to sell the idea to our countries, forgetting that much is already in place, including policies and activities. The only aspect of SUN that is new is the realization and appreciation that children include those that are not yet born.

–Academia/research stakeholder

Some donors and UN stakeholders noted that SUN was able to raise the status and priority of nutrition at the global level, which pushed their organizations to prioritize more funds for national nutrition activities. One UN stakeholder mentioned that coordination seems to have improved between UN agencies on nutrition due to participation in the SUN process.

Within the government, stakeholders noted that while planning was already underway for the UNAP prior to SUN, the movement may have helped quicken the pace of planning and release of the plan. One respondent said it provides a global perspective on Uganda's progress.

Defining Scale-Up

How has UNAP affected efforts to improve nutrition in Uganda? Stakeholders noted that the UNAP was developed even before Uganda signed on to the SUN movement. Government respondents noted the following changes since the inception of the UNAP:

- Increased communication and collaboration between government ministries and donors to support projects related to the UNAP.

- Some success harmonizing the various perspectives of stakeholder institutions.

- Brought national attention to undernutrition.

Further work to capitalize on these changes and to increase collaboration between ministries is needed.

Beyond the SUN Movement, SPRING wanted to explore how stakeholders perceived the term "scale-up" as an action, since many donors, UN groups, and academic institutions in Uganda (and globally) have been promoting scale-up as a measure of national nutrition plan success. Despite the focus on this term, no consensus has yet formed on what defines a successfully scaled up country, or what must be "scaled" to achieve success along this dimension (see SPRING's working paper "Defining Scale-Up of Nutrition Projects" for some examples of work in this area, as well as Hartmann and Linn 2008; CORE Group 2005; Victora et al. 2012).

SPRING asked key informants to define what scaling up nutrition means to them, and how they would measure it. SPRING probed on what it would take to reach that goal, and whether Uganda had the resources and capacities to do so.

'Scale-Up Means Reducing Undernutrition'

Of the stakeholders SPRING interviewed, approximately one-quarter responded that scale-up meant the reduction of undernutrition, or in essence, the "scaling down" of undernutrition.7

This sentiment was expressed by several stakeholders from the CSO, government, research, and UN sectors. The recurring theme was that the focus should be on the reduction of undernutrition, and the route is not necessarily standardized. A few of these respondents added that improvements must be sustained over multiple years if nutrition is to be truly scaled up.

While the 'reduced undernutrition' definition of scale-up is commonly used globally, it is also hardest to operationalize. Without naming specific leverage points, it provides little direction on how to prioritize these activities in Uganda and other countries. However, it does represent a concrete end-point on the continuum of scaled up nutrition, that of physical improvements in children, with proven links to better health, cognition, and productivity.

It's not an issue for me whether Uganda has scaled up nutrition, the basis is why we're doing all this? Because we have poor nutrition indicators, and we want to bring the stunting and anemia levels down. The issue is how we can do it as a country.

– UN stakeholder

Scaling up means having set nutrition indicators improved.

– CSO stakeholder

'Scale-Up Means Increasing Coverage of Nutrition Interventions'

The majority of the national-level interviews referred to successful implementation of a set of interventions as what constitutes scaled-up nutrition. Indeed, this aligns with many international definitions of scale, such as the 2008 and 2013 Lancet series set of interventions. SPRING (through other work) has developed a working definition in this vein as well: a process of expanding nutrition interventions with proven efficacy to more people over a wider geographic area that maintains high levels of quality, equity, and sustainability through multisectoral involvement (D'Agostino et al. 2014; Bhutta et al. 2013; Bhutta et al. 2008). It was unclear from the interviews whether this was the majority opinion because it was most operationally feasible or because of the influence of this international work.

Most of those adhering to the 'increased coverage of nutrition interventions' vision of scale-up were from the government, though one donor and a few UN respondents also fell into this group. Some respondents also noted reduction of malnutrition, but saw key interventions as the primary means to reach that goal.

Reaching more people with relevant services; Scaling up interventions that are proven to work.

–Donor stakeholder

And we need to see what has worked and what has not, pick up those that are high-impact [Lancet] – the target is 2015, which can accelerate the reduction of malnutrition.

–Government stakeholder

Taking forward what is already being done to a larger coverage scale in terms of districts and scope

– Government stakeholder

[It means] we have to implement evidence based, doable actions in the large scale, but that is the challenge as we have 112 districts. It needs funding to cover all districts.

– UN stakeholder

Some donors and UN groups have traditionally focused on curative nutrition-specific activities, but from our interviews indicated that a few are evolving their approach in Uganda.

And now we're saying nutrition is multisectoral, we need to scale up a whole comprehensive package of interventions. We've moved away from the traditional operation of the health sector focusing only on clinical nutrition to whole package of preventive interventions. That costs a lot of money to see a whole lot of behavior change at the community level.

– UN stakeholder

'Scale-Up Means Full Institution of Nutrition Policy'

Finally, some stakeholders identified scale-up as the full roll-out of UNAP or another nutrition-related policy. While this was not the majority opinion, respondents in this group represented every one of the stakeholder groups.

[Scaling up nutrition] means Uganda should have completed implementation plans, had them costed, and allocated resources for prioritized activities, making sure that there is proper planning to achieve expected results.

– Research/academic stakeholder

…Having leaders and other stakeholders prioritize nutrition investment in national plans and budget allocations…

– CSO stakeholder

Also means the need for a multisectoral approach, not doing it alone, holding each other's hand.

– Government stakeholder

Often policy scale-up was seen as an intermediary step to other definitions of scale, but given the amount of effort needed for full policy roll-out—not an insignificant undertaking—at least one stakeholder thought it would take until the end of the first UNAP.

Measuring Scale-Up

Within these definitions of scale-up, there is a need to measure success by each definition. Over a 10-15 year period, a country could move through all three definitions of scale-up, but given the time frame and the 5-year terms of most national nutrition plans, it is likely that all indicators or measures of scale will move forward in a sequence, and not at the same time. Below are descriptions of the traditional measures of "scale-up" for each definition, and some new process-related measures suggested by stakeholders in Uganda.

Measuring the 'Reducing Undernutrition' Definition

This definition allows ample independence to each country to define the best way to lower undernutrition according to context. Success would be tracked by how the UNAP affects nutritional status among those in the 1,000 days period. This approach does necessitate some assumptions to be made on attribution and the time frame within which changes can feasibly be measured. Figure 1 shows the current status, which is well-known information in Uganda.

Figure 1. Trends in Undernutrition Status of the Women and Children (BMI or WAZ-score)

**1995 and 2001 values need to be converted to WHO 2006 standard for comparability.

Other suggestions provided by stakeholders for tracking progress of this definition of scale-up are to make the progress of change in these indicators a larger factor—so that progressive improvement of an indicator over several years is more important than one-time period changes (this may reflect incredulity in Uganda over the large single-period reductions in anemia seen in the last DHS).

This could be operationalized as a moving average over time to smooth large single-year changes or by measuring these changes more consistently (possibly yearly), to detect the differences between sustained improvements and volatile change. Another suggestion was to track adolescent girls more consistently to better monitor the preconception period.

Measuring the 'Increasing Coverage of Nutrition Interventions' Definition

In this definition of "scale-up," Uganda would need to prioritize a smaller set of core activities, and success would be tracked by how the UNAP affects the coverage of these key interventions.

Despite a fairly consistent response regarding evidence-based interventions, there is a gap in data available on these interventions, as seen in Table 1. Tracking coverage of the 10 interventions named in the latest Lancet series (Bhutta et al. 2013) is not possible because there are no structures for tracking these data.

Table 1. Coverage of the Ten 2013 Lancet Nutrition-Specific Interventions, Latest Year

| Intervention | Maternal MMS [a] | Maternal calcium supplementation* | Maternal BPE supplementation | Salt iodization | EBF to 6 mos. | Appropriate complementary feeding education** | Complementary food supplementation | Vitamin A supplementation, 6-59 mos. | Zinc supplementation, 12-59 mos. | Mgmt of MAM and SAM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current coverage | National data not available | National data not available | National data not available | 99% | 63% | 44% | National data not available | 57% | National data not available | National data not available |

| Reasons this indicator is not currently collected | IFA is still the recommend supplement for mothers - 75% coverage | No national guidelines for calcium supplementation | No national guidelines, aside from those for HIV patients | Collected in UDHS 2011; percentage is of households tested | Routinely collected in UDHS | USPA 2007; not a routine survey; percentage is of children observed in facility visits who received counseling on feeding/BF practices) | Lack of standardized definition of this intervention may make it difficult to track | UDHS 2011; not routinely collected. | No national guideline for this | Facilities are supposed to start collecting and reporting into the DHIS2 system |

**Plus complementary food supplementation in food-insecure populations.

One UN stakeholder noted the difficulties in the area of information for monitoring these interventions:

One NGO is doing something somewhere, but nobody knows exactly what. Government has no data on how many health workers have been trained on IYCF. NGOs did the work, but they did not give information to the government. And those who were trained can't recall when the training happened or for how long.

Further suggestions for improving the measurement and evaluation of this intervention-defined scale-up include:

- Better monitoring of data quality to ensure accuracy of trends.

- Improved information sharing between key donor and UN groups to provide monitoring data for the government and the UNAP.

Measuring the 'Nutrition Policy' Definition

It is more difficult to define measures to track successfully instituted or scaled-up policy. In the UNAP, policy roll-out has a large role in Objectives 4 and 5, described in Table 3 below, but some goals, such as increased awareness and commitment, are very hard to track.

Table 3. UNAP Policy-Related Objectives

| Objective 4: Strengthen the policy, legal, and institutional frameworks and the capacity to effectively plan, implement, monitor, and evaluate nutrition programs. | Strategy 4.1: Strengthen the policy and legal frameworks for coordinating, planning, and monitoring nutrition activities. |

| Strategy 4.2: Strengthen and harmonize the institutional framework for nutrition from the local to the central government level. | |

| Strategy 4.3: Strengthen human resource capacity to plan, implement, monitor, and evaluate food and nutrition programs in the country. | |

| Strategy 4.4: Enhance operational research for nutrition. | |

| Objective 5: Create awareness of and maintain national interest in and commitment to improving and supporting nutrition programs in the country. | Strategy 5.1: Increase awareness of and commitment to addressing nutrition issues in the country. |

| Strategy 5.2: Advocate for increased commitment to improving nutrition outcomes. |

There are few current indicators defined for measuring increased buy-in to policy, harmonization, or roll-out of policy-related structures. Stakeholders suggested the following indicators for tracking scale-up of policy implementation:

- Number of meetings being conducted for specific nutrition or planning agendas.

- Level of coordination of different partners—quantifying the interaction between development partners and government stakeholders.

- Some measure of district ownership of UNAP policy or knowledge of policy.

Building from Strength

There was a general consensus between government, donor, research, and UN sector respondents that Uganda has political will to improve nutrition. Respondents noted there is strong political commitment to enact change, with leadership coming from no less than the prime minister to coordinate efforts for improved nutrition.

Many respondents also noted strong policy support for nutrition, not just through UNAP but through community-level policies and provision of guidelines on IYCF and other key areas. However, one respondent noted that sometimes good policies can sit on the shelf a bit too long before being implemented.

Within the government respondents, capacity for implementation was also noted as a strength, though some said it varied by departments/sectors. "Where there is a will, there is a way" when it comes to implementing nutrition programs at the community level, said one.

Challenges to Achieving Scale and Country Strengths

SPRING asked interviewees what resources and capacities would be needed to achieve scale, and what strengths would help Uganda overcome challenges. Responses coalesced in a few key areas.

Human Resources

When discussing challenges to scaling up nutrition in Uganda, stakeholders across sectors and groups said that human resources must be enhanced in order to achieve UNAP goals. Specifically, there is need for nutritionists at the following levels:

- Within Ministries, for planning and prioritizing projects.

- Within facilities, to conduct nutrition-specific activities.

- In districts and communities, to advocate, plan, and implement nutrition-sensitive activities.

Interestingly, stakeholders were divided on whether the supply of nutritionists was sufficient. Those working primarily in the area of health said that there were enough nutritionists being produced in Uganda, while those working in non-health sectors often disagreed. However, there was greater coherence on the lack of demand for such workers in the ministries, public service, and facilities. Without demand, no resources will be allocated to create these positions.

[We] need to create some establishment to absorb trained nutritionists. The government system has few structure[s].

- Research stakeholder

The capacity of available nutritionists may be a reason for differing opinions. There might be confusion about what skills nutritionists have and how they can be deployed in public service and policy and program development. It might be useful for university nutrition programs to consider some documentation and publicity of standard nutrition training in Uganda. At least one stakeholder alluded to the need for nutritionists to have some public policy skills for government positions.

Nutritionists are like planners, programmers, and policymakers. We need to get people who interact with people.

– Donor stakeholder

Taken together, stakeholder responses suggest the following steps to address ministry and public service human resource issues: 1) Educate hiring personnel about why nutritionists are needed, perhaps as part of an on-the-job training for civil servants; 2) Provide funding for recruiting; and 3) Provide support and in-service trainings to increase likelihood of nutritionists staying in position and dispensing evidence-based nutrition education.

Continuing education was also suggested for non-nutritionists in provider positions (e.g. doctors, nurses, midwives, community health workers, and agricultural extension workers). Suggested remedies ranged from general knowledge building and nutrition advocacy to a formal short-course on nutrition for public health professionals, such as the one Makerere University now offers on public health nutrition, practice, and management. Sponsorship from development partners for tuition may be needed. Less formal on-the-job training can also be supported for those at the community level, but a few stakeholders noted that given their broad mandate, community volunteer workers are often overloaded.

Coordination

Coordination was also universally discussed, though opinions on whether it was a strength or a challenge varied. Suggested changes also varied by stakeholder group. More about these nuances of this topic can be found in SPRING's coordination technical brief about coordinating in a multi-sector environment.

Financing

Financing of nutrition programs was also a significant aspect of the current and future challenges discussion for scaling up nutrition via the UNAP.

The case study will follow the 2013/2014 and 2014/2015 budget cycles, and once those data are available further comparisons can be made to the findings from the baseline interviews. A discussion about stakeholder views on funding as a constraint and innovative suggestions for overcoming this constraint will be provided in SPRING's forthcoming 2013/2014 budget technical brief.

Identity

The lack of a singular identity for nutrition was the final major challenge mentioned across stakeholder groups. Unlike a common disease group such as malaria or HIV/AIDS, respondents noted the difficulty of building interest in the multiple causes of malnutrition. This applied to community-level buy-in as well as national-level awareness.

There's a lot to learn from the HIV campaign, it was everywhere and you just can't escape it.

– Government stakeholder

Learn from AIDS – [was not taken seriously initially until later, when Uganda AIDS commission was established.] The strategy required each sector in the framework develop their own, and we did well!

– Government stakeholder

When AIDS came, guidelines were given to encourage the business to develop a workplace policy.

– Private sector stakeholder

The separation of nutrition, even within the same sector, may hinder efforts to push nutrition forward as a single issue. Within the Ministry of Health for instance, where nutrition-specific activities traditionally have a home, nutrition activity planning and decision making is separated into different units, which reduces the ability to advocate for larger blocks of nutrition funding. In some cases this separation inhibits discussion and collaboration between nutrition advocates within that ministry due to competing demands in each home unit. This also has an effect on prioritization of activities because it transfers budget tradeoff decisions to the departmental level, where nutrition may be less of a priority.

Mechanisms suggested for furthering the "identity" of nutrition in Uganda included creating a ministerial nutrition unit (not just in health, but perhaps in other key ministries), or a nutrition line-item in each sector's budget. Further innovative thinking about the "marketing" of nutrition as a unifying concept in Uganda is needed.

Discussion

It is important to note that the three definitions of scale-up emerging from the baseline PBN interviews relate to national nutrition planning, and should be interpreted with that in mind. Other definitions of scale, particularly for individual projects/interventions, are being explored elsewhere.8

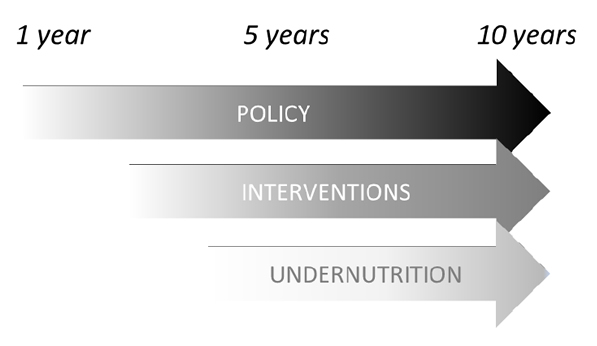

These three definitions feed each other and can be viewed as different phases of a long-term continuum. Figure 2 depicts this continuum – the depth of color represents forward progress.

Figure 2. The Continuum of Scale-Up

Several stakeholders mentioned how important it is to sustain commitment to scaling up nutrition and noted that it may take until the end of the second UNAP or even the third iteration of that policy before large-scale changes in undernutrition status are evident.

Uganda has the benefit of strong political will, policy support, and implementation capacity to support the continued roll-out and scale-up of the UNAP. It will be important to leverage that political will and policy support to make improvements to the nutrition workforce, particularly within the Ministries, before the end of the UNAP to avoid losing nutrition programming momentum.

Efforts to provide those implementing nutrition activities with a stronger identity, as has been done with other campaigns such as AIDS and malaria, can be made at the national and district levels. Several events, such as the nutrition marathon in Busenyi, the Kibaale District Nutrition Fair, and the National Nutrition Forum (Kasooha 2014; New Vision 2013; Kasanga 2013), have already increased awareness and created resolve on this issue. Further work to translate that increased awareness to action is needed. Dedicated nutrition financing will also help to solidify a movement for nutrition.

This case study will continue to follow the theme of scale-up and other domains of inquiry until the end of the study in 2015. SPRING is documenting how stakeholders create consensus on their approach to scale-up; plan for the next UNAP cycle to sustain scale-up; the monitoring and evaluation approach they take to gauge their own success; and how they mount solutions to the challenges noted here. In this exciting time of change for Uganda, there are many opportunities to overcome some of the most persistent barriers to scale-up through a multisectoral approach.

Footnotes

1 http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/goals/gti.htm

2 Cited in "Scaling Up Nutrition: SUN Movement Progress Report 2011-2012." Long form of the proceedings can be found here: http://apps.who.int/gb/e/e_wha65.html in "global nutrition policy review: what does it take to scale up nutrition action?"

3 http://www.un.org/en/zerohunger/

4 http://www.ghi.gov/about/goals/189070.htm

5 http://www.unscn.org/en/scaling_up_nutrition_sun/

6 http://scalingupnutrition.org/about/sun-country-approach

< id="7"p class="caption">7The interview prompt was "What does scale-up mean to you? What would it take to scale up nutrition in Uganda?"

8 See SPRING's work on scale-up for USAID implementing partners (D'Agostino 2014) and Alive and Thrive Initiative's recently released framework for scaling up IYCF programs (Alive and Thrive 2014).

References

Alive and Thrive. 2014. Framework for Delivering Nutrition Results at Scale. Washington, D.C.: Alive and Thrive.

Bhutta, Zulfiqar A, Tahmeed Ahmed, Robert E Black, Simon Cousens, Kathryn Dewey, Elsa Giugliani, Batool A Haider, et al. 2008. "What Works? Interventions for Maternal and Child Undernutrition and Survival." The Lancet 371 (9610): 417–40.

Bhutta, Zulfiqar A, Jai K Das, Arjumand Rizvi, Michelle F Gaffey, Neff Walker, Susan Horton, Patrick Webb, Anna Lartey, and Robert E Black. 2013. "Evidence-Based Interventions for Improvement of Maternal and Child Nutrition: What Can Be Done and at What Cost?" The Lancet 382 (9890): 452–77.

CORE Group. 2005. "'Scale' and 'Scaling-Up': A CORE Group Background Paper on "Scaling-Up Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health Services."

D'Agostino, Alexis. 2014. "Scale-Up: Preliminary Findings". presented at the USAID Internal Meeting, Washington, D.C., July 8.

D'Agostino, Alexis, Jolene Wun, Anuradha Narayan, Manisha Tharaney, and Tim Williams. 2014. Defining Scale-Up of Nutrition Projects. Arlington, VA: SPRING Project.

Government of Uganda. 2011. "Uganda Nutrition Action Plan 2011-2016: Scaling Up Multi-Sectoral Efforts to Establish a Strong Nutrition Foundation for Uganda's Development."

Hartmann, Arntraud, and Johannes Linn. 2008. Scaling Up: A Framework and Lessons for Development Effectiveness from Literature and Practice. Wolfensohn Center for Development Working Paper 5. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Global Economy and Development.

Kasanga, Kyetume. 2013. "Government To Drive National Nutrition Agenda." Office of the Prime Minister Press Office, December 3.

Kasooha, Ismael. 2014. "Over 60,000 Children Malnourished in Kibaale." New Vision, July 12.

New Vision. 2013. "MTN Supports Bushenyi Nutrition Marathon with sh15m." New Vision, December 2.

Victora, Cesar G., Fernando C. Barros, Maria Cecilia Assunção, Maria Clara Restrepo-Méndez, Alicia Matijasevich, and Reynaldo Martorell. 2012. "Scaling up Maternal Nutrition Programs to Improve Birth Outcomes: A Review of Implementation Issues." Food & Nutrition Bulletin 33 (Supplement 1): 6–26.