Executive Summary

SPRING conducted a two-phase multi-sectoral nutrition assessment for the USAID Nigeria during August–October 2017. We undertook the study to inform the development of a five-year, Global Food Security Strategy (GFSS) interagency country plan for the U.S. Government (USG) in Nigeria. In Phase One, SPRING conducted a desk review of the drivers of malnutrition. In Phase Two, we adopted a mixed methods approach and conducted an extensive field study in three of the four GFSS target geopolitical zones, covering four out of the seven target states. SPRING designed the fieldwork to achieve the following objective: To identify the primary drivers of undernutrition in Nigeria and explore potential opportunities for strengthening nutrition investments in GFSS targeted states. This report includes the key methodology, findings, and proposed recommendations from the field study.

SPRING developed household survey questionnaires, multiple key informant interview guides, and focus group discussion guides for different types of study participants, as well as a community observation checklist. We developed our data collection instruments to address the three objectives of the GFSS results framework and drew from validated tools, where applicable. We collected quantitative data from household surveys, qualitative data in from key informant interviews and focus group discussions, and community observations. The respondents included farmers, mothers of children younger than two years of age, and community leaders; small and large private sector firms; health and agriculture workers; and stakeholders from national and state government agencies, multilateral and bilateral donors, civil society organizations, and research institutions. Our household survey used non-probability sampling. Therefore, the results do not represent all the communities in the states. However, we presented the descriptive statistics to demonstrate the variations in indicators among the four states and to reinforce qualitative findings.

We used the three GFSS objectives to organize our findings from the fieldwork and to highlight the similarities and distinct features that emerged in each of the four states where we collected data. We describe the following issues: affordability and accessibility of agricultural inputs; market-related challenges; public sector challenges; lack of early warning systems and formal and informal safety nets; lack of dietary diversity; sub-optimal infant and young child feeding practices; challenges of public health services to address malnutrition; and poor water, sanitation, and hygiene practices. We also discuss challenges related to gender equity and women’s empowerment; and governance, coordination, and capacities within and among institutions that affect nutrition in the country. SPRING’s combined desk review and fieldwork presents a detailed picture of the GFSS focus states in Nigeria and potential program opportunities. We recommend an investment in seven areas using strategies and interventions customized to local contexts. Each recommendation listed below is described in more detail in the report to enable USAID Nigeria’s current and future investments to work together to achieve a wider reach and stronger integration for a sustainable impact on nutrition:

- Scale up high-quality information and communication on behaviors and practices that improve nutrition.

- Invest in a systems approach to deliver services supporting nutrition.

- Engage and empower women and girls through context-appropriate platforms.

- Ensure sustainable and diverse food production, consumption, and availability year-round.

- Prioritize pro-poor investments and interventions.

- Support nutrition coordination and roll out strategies and plans.

- Build strong evidence on agriculture-nutrition linkages.

I. Introduction and Background

Nigeria is a new target country of the U.S. Government’s (USG) Global Food Security Strategy (GFSS). The seven selected focus states in which to implement GFSS—Benue, Cross River, Delta, Ebonyi, Kaduna, Kebbi, and Niger1—are located within four of the six Nigerian geopolitical zones (USAID 2016). Depending on the security situation in the North East zone, the focus would also be on the four northeastern states of Adamawa, Borno, Gombe, and Yobe. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)/Nigeria also prioritized five value chains: rice, maize, soybean, cowpeas, and aquaculture. The selection of the focus states and value chains were based on the criteria shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Selection Criteria for GFSS States and Value Chains

| State Criteria | Value Chain Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

To inform the USAID country team’s development of its five-year GFSS interagency plan to reduce food insecurity, poverty, and malnutrition in Nigeria, the Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project conducted a two-phase multi-sectoral nutrition assessment. During Phase One, SPRING conducted a desk review of the drivers of malnutrition in Nigeria (see Annex 1). This review built on an analysis conducted in 2017 by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), which had an expanded scope focusing more on the existing literature and the national and regional data. The SPRING desk review revealed a significant diversity of cultures, livelihoods, and commodities across Nigeria, which informed the second phase of the assessment. SPRING carried out the fieldwork in three of the four target geopolitical zones and four out of the seven GFSS target states. To meet the objectives of its scope of work with USAID Nigeria2, SPRING’s fieldwork investigated the following question: What factors are responsible and what are the nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions that should be taken to address the country-specific causes of malnutrition in the GFSS target population?

This report with the completed desk study aims to accomplish the following research objectives:

- Synthesize the existing information on the immediate, underlying, and basic causes of malnutrition in Nigeria by focus state, subject to data availability.

- Examine how seasonal access to markets, production practices, and food purchases impact household food security and nutrition.

- Explore how traditional practices and cultural norms may affect malnutrition to inform the most appropriate strategies to support different populations.

- Use the existing literature and data to compare the GFSS focus states in the north to the states in the south.

- Suggest lessons learned from current and past development and humanitarian activities to minimize unintended negative consequences in the design of future nutrition programs.

- Share what national, state, and local government area (LGA)-level resources are available to support nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive activities.

Overview of Nutrition Situation

Nigeria’s Demographic and Health Survey (2013) reports small improvements in rates of stunting: from 42 percent of children in 2003 to 37 percent of children in 2013 (DHS 2013). However, as a country, Nigeria is facing a nutrition crisis on multiple fronts. One out of every three Nigerian children is stunted, and 7.8 percent of children are wasted3. An estimated 1.9 million children suffer from severe acute malnutrition, placing them at immediate risk of premature death. An estimated 71 percent of children, and 48 percent of women of reproductive age, are anemic (Stevens et al. 2013). Women’s nutrition is of particular concern, with a double burden of thinness (11 percent) and obesity (25 percent) (DHS 2013). In general, undernutrition and health outcomes are worse in the North East and North West zones, compared to the Southern and Central zones; but Nigeria is a large, diverse country and the prevalence of undernutrition varies widely across, and even within, states.

Although chronic and seasonal nutrition problems are prevalent throughout the country, the impact of conflict and other shocks has resulted in acute levels of food insecurity, and potential pockets of famine in the North East zone (FEWSNET 2017a). An estimated 3.1 million people in the Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa states received emergency food assistance or cash transfers in the first half of 2017 (FEWS NET 2017a).

Nutrition in Global Food Security Strategy

The GFSS charts a course for the USG to help achieve global food security and improve nutrition by focusing on three objectives: (1) inclusive and sustainable agricultural-led economic growth, (2) strengthened resilience among people and systems, and (3) a well-nourished population (USAID 2016). Undernutrition—especially among women and children during the 1,000 days from pregnancy to a child’s second birthday—leads to lower levels of educational attainment, productivity, lifetime earnings, and economic growth rates. In short, nutrition is central to sustainable development and is necessary to make progress on issues that include health, education, employment, poverty, inequality, and the empowerment of girls and women.

The GFSS aims to break silos, integrating programming across sectors for maximum impact for improved nutrition. However, the linkages across sectors are not always well understood or considered in program design and implementation. For this reason, SPRING decided it was important to use the GFSS conceptual framework as a basis for data collection and the structure of this report; this will enable us to purposefully point to opportunities for affecting nutritional outcomes across all three GFSS objectives. Under GFSS Objective 1, if nutrition-sensitive approaches are applied, the agriculture sector can increase the availability of affordable, diverse, and nutritious foods, as well as generate opportunities for income growth among the poor, increasing their ability to afford these foods, as well as to pay for health and hygiene products and services needed to reduce hunger and improve nutritional status.

Under GFSS Objective 2, increased resilience among people and systems is necessary for men, women, and families to reduce, mitigate, adapt to, manage, and recover from shocks and stresses that threaten food security and nutritional status. They can also sustainably escape poverty and be better able to access the quality foods and health care that lead to better nutrition when nutrition-sensitive agricultural livelihoods are protected.

Of course, under GFSS Objective 3, nutrition-specific interventions must be linked to sustained availability and access to nutrient-rich foods and good sanitation and hygiene. These outcomes must also be supported by Objectives 1 and 2 in order to increase consumption of nutritious and safe diets, maintain more hygienic household and community environments, and increase use of direct nutrition interventions and services to decrease disease burden and sustain a well-nourished population.

Clearly, under GFSS, both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions are necessary—and must work together—to achieve improved nutrition among women and children in rural communities.

Agriculture-Nutrition Linkages

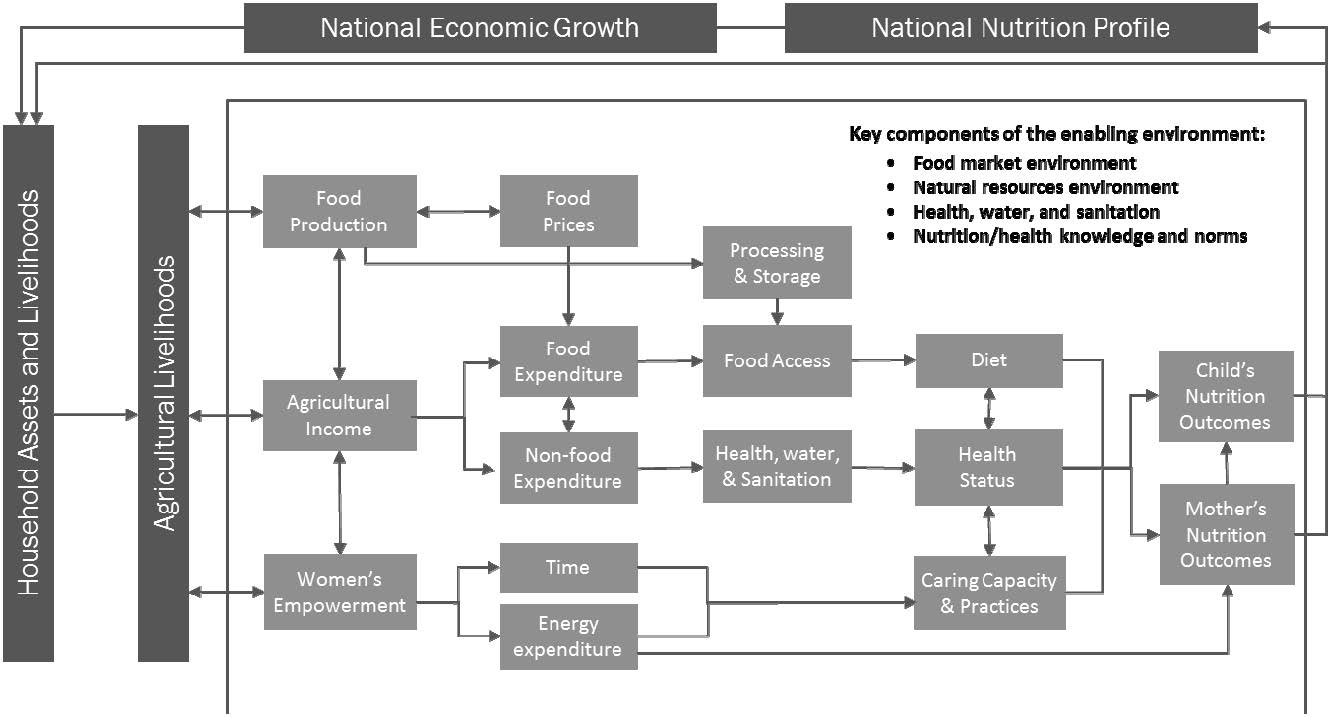

In 2014, SPRING developed a conceptual framework, which was adapted from earlier work by Kadiyala et al. (2014), and that identifies three primary pathways linking agriculture and nutrition (see Figure 1):

- Food production to make diverse and nutrient-rich foods available for consumption

- Income to purchase nutritious foods and pay for health care services, as well as improved water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) products and services

- Women’s empowerment, including equitable access to and control over household income and productive resources, and joint decision making around time, labor, and household expenditures.

Figure 1. Agriculture-Nutrition Pathways

These pathways target individual smallholder farm households and the decisions and actions available to them to foster better nutrition. The “enabling environment” or external factors at the community, regional, or national level also affects these households. The enabling environment includes the prevailing agrifood and market system; the availability of natural resources; accessibility of health, water, and sanitation services; cultural and gender norms; and policy. The Agriculture-Nutrition pathways support the GFSS objectives and provide a guiding framework to this report to analyze challenges and opportunities to improve nutrition outcomes in Nigeria. Throughout the report, we strive to ground the findings and recommendations in the pathway(s) most relevant to their potential effect on nutrition and to reflect opportunities for linking nutrition-sensitive and nutrition-specific programming.

In section II, we describe our study design and data analysis. Section III shares our major findings presented by GFSS objectives, as illustrated in the results framework (Annex 2). Throughout, we make explicit efforts to link each finding to nutrition and to highlight the similarities and differences across the states where we conducted our fieldwork. The last section proposes a list of recommendations for the Mission to consider in their investment and program plans.

II. Methodology

SPRING employed a mixed methods approach in the assessment and conducted household surveys, key informant interviews (KIIs), focus group discussions (FGDs), and community transect walks. The SPRING team sent three study teams to four states: Kebbi, Niger, Benue, and Cross River, and we kept a base in Abuja. See Annex 3 for the details of the fieldwork timeline. A research lead and a research assistant conducted KIIs with national level nutrition stakeholders, primarily in Abuja, but also in Ibadan and by phone. The SPRING field teams comprised one team leader, five research assistants, and one SPRING support staff. All the data collection instruments are included in a separate document: Compendium of Data Collection Instruments.4

Data Collection Instruments

Household survey: SPRING developed a comprehensive household survey comprising six modules that correspond to GFSS intermediate results (IRs). We administered the questionnaire to the parents of children less than two years of age. In households with more than one child under two years of age, questions referred to the youngest child. Both men and women responded to questions about the home gardens. Only the household head (men or single mothers) answered questions about agricultural production, capacity to plan for stresses, and coping strategies. Only caregivers (married mothers and single mothers) responded to questions about household food consumption (24-hour recall) and infant and young child feeding (IYCF), and WASH behaviors, including knowledge and/or application of the 10 core nutrition interventions recommended by The Lancet 2013 nutrition series (Bhutta et al. 2013). SPRING research assistants administered the surveys in English, Pidgin English, or Hausa. Because not all participants provided meaningful responses to each question of the household survey, the sample size varies for a few questions. The survey included questions that allow for multiple responses and, as a result, in those cases, the sum of the corresponding percentages exceeds 100 percent. All figures shown in this report were rounded to the nearest whole number.

Key Informant Interviews: The SPRING team developed separate KII guides for different types of key informants: state and LGA personnel across sectors, nongovernmental organization (NGO) staff, community leaders, smallholder producers, commodity dealers, commodity aggregators, and market leaders. SPRING selected national-level key informants from a range of government agencies, bilateral and multilateral donors, research institutions, civil society organizations, and the private sector. To triangulate data elicited from other instruments, SPRING worded the questions in these guides to correspond to GFSS objectives.

Focus Group Discussion: SPRING developed two types of FGDs: one to assess gender dynamics and a second to assess the seasonality of food availability. Through the gender FGD, we examined individuals’ perceptions of gender roles in agricultural production, processing, sales, and food preparation. Our FGDs on seasonality of food availability asked small groups to construct 12-month food calendars describing the trends in their community in terms of seasonal consumption, availability, and affordability of 12 groups of foods (Kennedy et al. 2011). Both types of FGDs were limited to 8–20 participants, segregated by gender. The gender FGD took approximately an hour to administer and the food calendar FGD averaged about two hours.

Community Transect Walk: The community transect walk guide recorded structured contextual information about communities visited. Using this tool, research team members noted their observations of transportation infrastructure, land use, agricultural processing facilities and/or equipment, electrification, the WASH environment, and characteristics of local markets.

See Table 2 for a summary of the numbers of household surveys, KIIs, FGDs, and community transect walks conducted by each state team. Annex 4 provides a more detailed description of the respondents the SPRING team collected data from and Annex 5 lists the national-level stakeholders interviewed.

Table 2. Use of Data Collection Instruments

| Data Collection Methods | Kebbi | Niger | Benue | Cross River | Abuja |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household surveys | 89 | 37 | 73 | 119 | - |

| Key informant interviews | 93 | 60 | 59 | 49 | 24 |

| Focus group discussions | 24 | 4 | 7 | 13 | - |

| Community transect | 6 | 6 | 8 | 6 | - |

Strengths and Limitations

Table 3 summarizes both key strengths and limitations for the current assessment:

Table 3. Strengths and Limitations

| Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|

|

|

III. Findings

Objective 1: Inclusive and Sustainable Agriculture-led Economic Growth

Agriculture is the main livelihood for most households in Nigeria, particularly in the GFSS zone of influence. As noted in SPRING’s desk study, farming systems—and diets—center on staple food crops. To identify opportunities for agriculture to better support nutrition outcomes, the team developed an understanding of farming systems in each state, including developing a list of major crops produced, by state (see Annex 6). Of the USAID priority crops, maize is widely grown in Niger and Benue (>60 percent of respondents), cowpea in Niger, and soybeans in Benue; most households grow rice: in Kebbi (74 percent), Niger (94 percent), and Benue (56 percent). Kebbi and Niger produce appreciable quantities of millet and sorghum, while tubers are more prominent in the central and southern states: Benue and Cross River. Production of the USAID priority value chain crops (except rice) is low in Cross River because the state has prioritized cocoa, oil palm, and rice; and both public and private support systems focus on producing these three crops.

Constraints to production in the four target states limit the ability of families to feed themselves from their own production year-round. As a result, most households are net buyers of food, and they rely on less-preferred staple foods when their own stores are low; this is illustrated by our FGD on the seasonality of food availability. However, as noted in SPRING’s desk study, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) estimates that most areas of the country will have sufficient food production in the 2017/2018 harvest period to meet caloric needs (FEWS NET 2017a). In addition, agricultural production in all four states is labor-intensive, placing demands on pregnant and lactating women, especially during peak labor periods. This affects their own nutritional status, as well as that of their unborn child. Landholdings are small and fragmented and there is significant dependence on rainfed agriculture, except Kebbi, which has a strong culture of irrigated farming. The typical farmer we interacted with was a small-scale farmer. The land size of survey respondents ranged from two hectares for rice and millet in Kebbi to much smaller average landholdings in Cross River where farmers cultivated less than one hectare, on average, for all crops. See Annex 6 for a breakdown of average land size cultivated per crop and the location of study respondents.

Both availability and affordability of nutrient-rich foods affect dietary diversity, including fruits, vegetables, and animal source foods—fish, eggs, and meat and dairy products. The desk review reported low dietary diversity in Nigeria, nationally, which explains, for example, that women in six states ate an average of 5.8 different types of food out of 14 food categories (Ajani 2010). Our field survey findings corroborated this. We found that commercial vegetable production was low (less than 10 percent in all states except Kebbi), although a large percentage of respondents have home gardens (as many as 69 percent of respondents in Benue, for example). Home gardens produce a variety of fruits and vegetables (see Annex 6), which study participants reported both selling and saving for home consumption.

For livestock and fish, Kebbi had the highest percentage of animal owners—cows, poultry, goats, and sheep—for both sale and home consumption. The communities visited in every state, except Cross River, had a high percentage of poultry owners; however, the survey data suggest that households keep chickens only for meat and not eggs, as anecdotal evidence suggests that egg consumption is low because of cultural preferences. Aquaculture is rare among smallholder farmers in these locations, although a majority is engaged in artisanal fishing for sale and home consumption. Aquaculture requires large startup capital and running costs—beyond the reach of most farmers. Annex 6 includes details on livestock production across the four states.

Affordability and Accessibility of Agricultural Inputs

The cost of necessary inputs directly affects a farmer’s ability to earn income from agriculture. At the household level, the high cost of inputs influences decisions about what to grow and how to prioritize household income. High input costs also affect what is available at local markets for purchase and, ultimately, consumption. Physical and financial access to inputs is a problem across all four states that SPRING visited. In Niger, Benue, and Cross River, good quality inputs, including seeds, chemical fertilizers, and pesticides—as well as farm implements or equipment (e.g., tractors and irrigation systems)—are not available, particularly in remote sites. The few available inputs tend to be low quality. Industry key informants (KIs) provided anecdotes about unscrupulous intermediaries filling empty fertilizer bags with sand and selling them to rural farmers. Distribution systems appear to be better in Kebbi than in the other three states, but inputs are not affordable for the average farmer across all four states. The lack of access to input limits farmers’ ability to produce a range of nutritious foods and it contributes to sub-optimal yields, compromising year-round food security. Mechanization is uniformly poor in the four states and farming requires long hours and hard labor by both men and women. Intense labor requirements place women of childbearing age at particular risk for undernutrition and ill health. Most farmers cannot afford to own their tractors or other mechanized inputs, and access to rental services is inadequate across all locations (Takeshima et al. 2013). Table 4 shows the number of respondents that reported using inputs and loans; Table 5 shows the responses to the question of adequacy for each type of input. The tables summarize responses to the questions “do you use inputs, yes or no” followed by “did you have enough, yes or no.” While the available inputs vary by location, the responses suggest that farmers are aware of the need or benefit of inputs and rarely think they have sufficient amounts.

Table 4. Respondents Using Selected Inputs and Loans (percentage)

| Location | Seeds | Fertilizers | Herbicides/Pesticides | Loans |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Kebbi (n=89) | 97 | 85 | 82 | 21 |

| Niger (n=34) | 97 | 91 | 88 | 41 |

| Benue (n=70) | 97 | 71 | 89 | 9 |

| Cross River (n=93) | 39 | 19 | 28 | 6 |

Table 5. Respondents Reporting Sufficient Access to Selected Inputs and Loans (percentage)

| Location | Seeds | Fertilizers | Herbicides/Pesticides | Loans |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Kebbi (n=89) | 66 | 11 | 9 | 6 |

| Niger (n=34) | 68 | 35 | 38 | 21 |

| Benue (n=70) | 54 | 14 | 24 | 0 |

| Cross River (n=93) | 24 | 6 | 9 | 2 |

Because production is seasonal, suboptimal—in quantity and variety—yields contribute to lean seasons for farming households, which lead to low household food stores, low incomes, and inadequate caloric, micronutrient, and/or protein consumption. Farmer households consume a portion of the crops they produce. The amount and quality of a harvest could suffer from insufficient or low-quality inputs, directly affecting the food security of the household. High input costs reduce net earnings and the ability of households to designate part of their budget to purchase food and health services. In the context of marginal incomes, the decision about how much to invest in the household livelihood versus meeting the costs of nutrition through diverse food purchases and meeting health and WASH expenses is made even more difficult. Avoiding high input prices may also reduce the overall availability of quality foods in local markets, thereby affecting food access for the entire community.

Market-Related Challenges

Smallholder farmers participate in markets in many ways—as producers, processors, and retailers—but also as consumers. SPRING observed that while farming households tend to keep some of what they produce for home consumption, they rely on their local market to supplement their diet. What is available for purchase and the prices of food in local markets affects the quality of diets, particularly during lean seasons. In this finding, we discuss three major market-related challenges: (1) post-harvest processing of target value chain commodities, (2) access to output markets, and (3) market seasonality and food availability.

Post-Harvest Processing

Post-harvest processing can affect nutrition through both the consumption and income pathways and contribute to year-round food security. It reduces post-harvest losses and introduces preservation practices, which, together, may extend the amount of time that food is available within households; it also increases the opportunity for value addition, contributing to increased incomes.

With improved post-harvest processing, value chain actors stand to earn more income by diversifying and improving the safety, quality, and desirability of food items available for sale and purchase in markets throughout the year. Additionally, post-harvest processing activities create employment opportunities, providing a vehicle for women’s empowerment through new roles, skills development, and opportunities to control income. The following section describes processing challenges for the USAID target value chain commodities observed in the four states.

Rice: Rice production is strongly emphasized in Kebbi, which has led to strong linkages between producers and buyers. Large agro-processing industries have outgrower schemes, which are supported by extension agents who receive a stipend for teaching farmers proper agronomic practices and that supply growers with improved seeds and other inputs. After harvested, the processors pick up the paddy directly from the farms. This outgrower approach ensures that farmers have a regular market outlet for their produce; however, these schemes appear to discourage good post-harvest handling and storage practices because farmers sell all the produce at harvest time. Other states do not have this situation. Despite Cross River’s focus on rice, rice paddy is transported to the neighboring state, Ebonyi, for processing, often placing the cost and burden of transport on the producer. Benue and Niger have functioning rice mills, but the farmer-industry linkage is not as strong as in Kebbi. Household level post-harvest practices and processing techniques in all states are rudimentary, labor intensive, and archaic. For instance, parboiling rice is still, primarily, done in large, open pots—the paddy is put directly in contact with water instead of steam.

Smallholder households grow rice for both consumption and sale. Having a strong link to secure markets is key to household food security, even if the prices are low, because farmers can calculate how much rice to sell and how much to hold for home consumption in a specific year. Additionally, the SPRING survey team found no evidence of market demand for nutrition-sensitive processing that could add to or maintain the micronutrient content of frequently consumed foods, such as rice.

Maize, soybean, cowpea, and aquaculture: SPRING did not find any processing or value addition activities in the states associated with the other GFSS focus crops; most receive minimal processing for consumption—like pap for maize or moinmoin for cowpeas. Benue has seen some success in linking farmers to soybean markets via two major soybean processors: Hule and Sons in Wanune (producing unrefined crude oil) and Seraph oil (producing refined vegetable oil and soy milk concentrate for animal feed) in Makurdi. The USAID-funded Maximizing Agricultural Revenue and Key Enterprises in Targeted Sites II (MARKETS II) activity linked farmers to these processors by helping them meet the processors’ foreign matter and moisture standards. The examples in Benue and Kebbi show that, with appropriate support, farmers can supply formal markets.

Access to Output Markets

In the four target states, accessing formal markets is a challenge because of the inability to meet quality standards. When farmers cannot meet industry specifications, as with most crops, they face low, unreliable incomes from sales; and they are less likely to be able to afford nutritious diets and health services. Additionally, local markets are probably selling products that do not meet food safety standards, increasing the risk to local consumers—including the farming households—of consuming foods with toxins or chemicals.

The inability to meet quality standards means producers cannot supply commodities to large buyers, including processors. In particular, poor post-harvest and storage practices (e.g., damp storage leading to aflatoxin contamination) compromise their ability to satisfy moisture and foreign content standards required by industry players. Additionally, farmers sometimes use dangerous chemicals to store their produce, leaving residues that are unacceptable to large buyers trying to meet national or international food safety standards. Our KIIs and household surveys suggest that many farmers do not know or have the skills to meet industry standards, nor do they know who their potential buyers are outside their immediate environment. In addition, farmers lack the organization skills, connections, or knowledge to access these buyers. Farmers in the target area are generally not organized into cooperatives, do not aggregate or grade their production, and individual farmers produce too little produce to interest industrial buyers. As a result, most farmers sell their produce in informal, local markets with minimal quality standards. Not only is the produce usually underpriced but also potentially in violation of health and safety standards for human consumption.

Key informants stated that, with proper training, farmers could meet standards for industry and exports. Benue is attempting to do this; NGOs and the Agricultural Development Projects (ADP) are providing training to farmers to meet the export standards for yams (e.g., uniform sizing of yams for exports). The experiences of Kebbi and Benue with rice and with soybeans show that it is possible to link small-scale producers and industry. Farmers are willing to adopt improved post-harvest practices, potentially improving the value chain, reducing post-harvest losses, and creating employment opportunities and entrepreneurship.

Market Seasonality and Food Availability

Most farmer households obtain their foods from the same local markets that they supply and, because production is generally rainfed, food availability is seasonal. The patterns of seasonal food availability are similar across all states—cheap foods are plentiful in markets during the first few months after the harvest. Food stores diminish and market prices rise as the lean season approaches, forcing farmers to buy the same foods they may have sold to markets at the time of harvest for higher prices. Diverse food items are available during the harvest, including grains, legumes, vegetables, and fruits. Because animal source foods are expensive year-round, the harvest season—when there is income from sales or around holidays—is the only time that households might include them in their food budget. Each state has different preferred food groups: in Kebbi, households consume cereals and grains year-round, while households in Benue and Cross River favor tubers (yam and cassava). Households allocate resources to purchase these staple foods year-round, regardless of price. During the lean season, the quantity of all food types consumed is drastically reduced. FGD participants revealed that they tend to switch to less preferred substitutes when certain foods are not accessible, such as gathering wild drought resistant vegetables in the dry season when vegetables are scarce in the market.

The most apparent effect of seasonality and food availability on nutrition is that household access to food is limited during the lean season. Data from a national survey done in 2013 found that one in five households nationwide experienced food shortages at some point in the past 12 months, which primarily affected urban households (23 percent) and the southern zones (34 percent in the South East and 22 percent in the South West) (Nigeria Bureau of Statistics 2016). During this season, food is not as available and more expensive, and household income is lower. Many households resort to coping mechanisms, such as limiting meal quantities and frequency, further limiting their already scarce dietary intake. Additionally, depending on the agricultural cycle, workload requirements may be higher than they are during the time of year when food is plentiful—increasing the need for food in the context of scarcity and high prices. Given this season of especially strained income, to consume enough calories, households may reduce spending on health and caregiving needs.

Public Sector Challenges

The three main channels through which state governments interact with the agricultural sector include (1) the ADP, the Government of Nigeria’s (GoN) agricultural extension service, (2) research institutions, and (3) various government regulatory agencies. The SPRING team found challenges within and among all three, limiting the potential of agriculture to improve nutrition outcomes in the four states.

Agricultural Development Projects

ADPs across Nigeria play a facilitating role in the production of crops and livestock (including aquaculture), input distribution, farmer training, and adaptive research; they work alongside extension efforts to increase productivity, incomes, and livelihoods in rural areas. Unfortunately, the ADP system in all four states is under-resourced, inefficient, and unable to serve its intended purpose. Benue had fewer than 30 ADP extension officers (resulting in a ratio of one extension agent to over 50,000 farmers), and the state government has not funded the Benue ADP for six years. Similarly, Cross River has 96 active extension agents, with a ratio of one agent to every 5,000 farmers. The ADP system across Nigeria is inadequately funded, leading to aging personnel (with no replacement hires) who are overworked, under-trained, and unmotivated. Donors such as World Bank, IFAD, and USAID—have supported extension operations in many states, leading to donor dependency. The lack of resources severely constrains the ADP from providing timely information to farmers on prices, climate shocks, and best practices. Even though the GoN recognizes their part to support multi-sectoral outcomes for nutrition, state-funded training for ADP agents is almost non-existent and standard curricula at the university level lacks nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices or concepts for agriculture majors.

Agricultural Research

Agricultural research institutions and universities are present in all the states, yet nutrition and nutrition-sensitive agriculture are not research priorities and the research-extension-farmer linkage is weak. In Kebbi, the National Cereal Research Institute (NCRI) substation has existed since 1963; it has a mandate to conduct research on rice, maize, soybean, groundnut, and sugarcane. Based on interviews with NCRI staff, SPRING learned that research efforts prioritize yields and disease resistance over nutritional value and quality. While there is a theoretical linkage between the agricultural universities (particularly in Benue) and the ADP, in practice, research findings do not reach farmers, despite the potential benefits to farmers if they have access to improved, climate-smart agricultural practices. For instance, while the soil of Benue can support cowpea production, it is difficult to produce because of severe pest infestation. Research-farmer linkages can provide information on how to manage this challenge and provide advice on alternative farming system solutions, while promoting the nutritional properties of alternative crops, like cowpeas.

Public programs like the ADP and publicly-funded research institutions can help improve nutrition by influencing behaviors and changing environments. The ADPs provide services to increase productivity and incomes, which could mean an increased accessibility of nutritious foods. Research institutions could conduct more innovative research on applicable solutions like drought or pest resistant seed or biofortification. Additionally, in testing research findings, research organizations could influence behavior change among farmers to adopt improved practices and to increase the demand for nutritious food.

Government Policy and Regulatory Systems

The policy and regulatory environment in all the states is chaotic, limiting the ability of private sector actors to engage with small-scale producers and introduce nutrition-related products and services. Agriculture is on the second schedule, part II number 18 of the concurrent list of the 1999 constitution. As a result, the federal government cannot impose policies on states; therefore, while strategies to support private sector growth exist at the national level, they do not at the state level. State governments have also struggled to provide a business-enabling environment and, as a result, very few successful agribusiness companies or other private sector players influence the types and quality of food available in the markets. Key informants complained about an unclear and extractive tax system, and a conflicting and burdensome regulatory environment. Agencies are not coordinated, resulting in a plethora of fees and regulations that businesses perceive as oppressive. Tightly regulated private sector growth may also be stifling farmers’ income, affecting their production capacity and, ultimately, their ability to provide for their households. In addition to limiting opportunities to generate income, barriers to private sector growth may also stifle innovative products and services that can improve nutrition, such as hermetically sealed bags for storage, preserved food products, convenience goods, and female-owned businesses.

Objective 2: Strengthened Resilience among People and Systems

As reported in the desk study, an assessment by Mercy Corps found that one-third of households across Nigeria reported some form of shock or hazard during 2010–2016. Five percent of households specifically reported experiencing conflict, primarily in the North East zone and the Niger Delta region; and conflict in this region was linked with increased rates of malnutrition, particularly wasting and reduced food consumption scores. The desk study also found that the largest expense for most Nigerian households is food. In 2013, 57 percent of disposable income went toward food consumed at home. Factors—such as high rates of poverty, increasing food prices, and insufficiently developed and diversified livelihood opportunities—present risks to Nigerian families’ ability to purchase food and nutrition-related services. In 2013, roughly one in four households reduced the number of meals taken in the past seven days because of economic shocks, with food price increases the most frequently cited source of shock (Nigeria Bureau of Statistics 2016). Compounding these risks is a national reserve system that is inadequate for meeting national needs when shocks occur (Ndukwu, Akani, and Simonyan 2015).

To ascertain the existing levels of resilience, and to characterize common shocks and coping strategies in the target area, SPRING included questions on the household survey questionnaire to determine the contributors to vulnerability. The responses to this survey section helped us understand challenges associated with strengthening resilience at the household and systems level. In line with the findings of the desk study, SPRING’s household survey identified drought, flooding, and food price increases as being the most common shocks experienced by respondent households, all contributing to food insecurity. In fact, our survey found that household food insecurity is a major issue across the four states, with approximately 25 percent of Kebbi respondents to almost 50 percent of Niger respondents indicating difficulty accessing sufficient food for their household in the past seven days (see Table 6).

Table 6. Households with Difficulty Accessing Food in the Past Seven Days (percentage)

| Kebbi (n=89) | Niger (n=34) | Benue (n=70) | Cross River (n=93) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 24 | 49 | 31 | 37 |

| No | 76 | 37 | 62 | 11 |

SPRING’s key findings showed that high food prices occur every lean season, as reflected in the affordability section of the seasonal food FGD. When food is unaffordable, households try to simply “fill the stomach,” with little attention to the quality of calories consumed. To better understand events that lead to food insecurity and how households manage periods of food insecurity, the SPRING survey asked about the main types of shocks affecting families, as well as the common coping mechanisms.

All states visited are close to large bodies of water and most communities are infrastructure deficient, lacking drainage to aid in water management. As a result, floods are routine destructive occurrences that destroy lives and properties. The recent floods in Benue in August 2017 were particularly destructive and resulted in loss of livelihoods and assets and, in many cases, food insecurity and hunger. Additionally, flooding affects health outcomes; key informants spoke of an increase in malaria from standing water after the flood, and said that their houses were more prone to mold or left structurally unsound.

Herdsman-farmer clashes have become common across the country, but particularly in the North Central regions. This violence has resulted in loss of assets, abandonment of farmland, and internal displacement. This has a long-term negative impact on farmers, depending on their support system. States have responded by banning open grazing and mandating the use of ranches. The law against open grazing in Benue, for instance, took effect in November 2017, despite intense resistance. Other shocks mentioned in household surveys include a chronically ill household member (devastating, due to the lack of health insurance or decent rural health care system), livestock disease and death, as well as crop failure. A sizable percentage of survey respondents mentioned weeds and pest infestation as a major shock made more severe by their inability to afford the quantities and types of inputs needed to mitigate these threats. Currently, innovative input dealers are trying to provide microfinance to farmers, enabling them to access inputs in Benue. The interest rates attached to these loans—five percent per month—reflect the risk associated with working with this highly vulnerable population. Table 7 shows the percentages of households that faced the shocks most commonly named in our survey.

Table 7. Most Prominent Shocks Faced by Households in the Past Year (percentage)

| Causes of Shock | Kebbi (n=89) | Niger (n=34) | Benue (n=70) | Cross River (n=93) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drought | 18 | 9 | 19 | 3 |

| Flood | 27 | 41 | 53 | 8 |

| High food price | 85 | 41 | 36 | 32 |

| Lack of agricultural inputs | 45 | 18 | 26 | 20 |

| Late rainfall | 31 | 50 | 10 | 18 |

| Chronically ill household member | 38 | 32 | 20 | 9 |

| Weeds and pest | 35 | 41 | 50 | 17 |

| Crop failure | 11 | 12 | 24 | 10 |

| Livestock disease | 36 | 3 | 26 | 0 |

| Livestock death | 4 | 6 | 11 | 3 |

| Insecurity/violence | 0 | 3 | 37 | 0 |

The most common strategies used by respondents to cope with food insecurity are to buy less expensive food and to borrow food to alleviate hunger (see Tables 8 and 9). The quality of help that poor rural households can access depends on the strength of their social networks. Information from key informants reveals that the neighbors in the affected communities that a household might turn to for help are likely facing the same challenges.

Table 8. Coping Responses within the Past Seven Days (percentage)

| Coping Response within the Past 7 Days | Kebbi (n=89) | Niger (n=34) | Benue (n=70) | Cross River (n=93) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relied on less expensive food | 16 | 26 | 17 | 26 |

| Borrowed food, from friend or relative | 21 | 26 | 6 | 26 |

| Limited portion size | 11 | 29 | 7 | 23 |

| Restricted consumption by adults | 8 | 6 | 1 | 18 |

| Reduced number of meals | 13 | 21 | 7 | 20 |

Table 9. Coping Response within the Past 12 Months (percentage)

| Coping Response within the Past 12 Months | Kebbi (n=89) | Niger (n=34) | Benue (n=70) | Cross River (n=93) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sold more animals than usual | 38 | 56 | 24 | 3 |

| Looked for temporary job outside the community | 42 | 56 | 31 | 14 |

| Borrowed more money than | 38 | 44 | 19 | 29 |

| Worked for food only | 20 | 21 | 7 | 30 |

| Spent savings | 71 | 68 | 61 | 33 |

| Sold land | 2 | 9 | 11 | 1 |

| Sold productive assets (e.g. grinding machine, motorcycle | 10 | 15 | 7 | 10 |

| Reduced expenses on health and education | 26 | 18 | 13 | 12 |

| Reduced expenses on agricultural, livestock or fisheries inputs | 30 | 21 | 11 | 8 |

| Entire household migrated | 1 | 3 | 26 | 1 |

| Child labor (engaged children to earn income) | 20 | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Married girls/gave them in exchange for money | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Took children out of school | 10 | 9 | 6 | 9 |

| Sold last female animals | 3 | 18 | 3 | 1 |

| Sold all animals | 2 | 9 | 1 | 0 |

Early Warning Systems Inadequate To Warn or Prepare Vulnerable Households before Shock/Crisis

Across the states, information systems to warn about pending disasters or emergencies function poorly. Key informants in Benue reported TV and radio ads warn about potential flooding, but the warnings only told them to move, without offering any concrete alternatives. With nowhere to go, most remained in their homes and lost crops, animals, and, for some, human lives. Without information systems advising farmers of events that affect production, they cannot manage the potential impacts on their livelihood. The Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NiMet) regularly releases information on the climate situation in the country (through press briefings), advising of floods, early cessation of rains, and droughts. This information generally does not reach smallholder farmers, leaving them without notice or actionable plans.

Unexpected shocks deplete a household’s already scarce resources. In some cases, environmental shocks also compromise future production activities. With few productive assets, the costs associated with recovering from shock forces families to face food insecurity, health risks, loss of income, or high levels of indebtedness just to access food or health care resources.

Inadequate Formal or Information Safety Nets in Place To Assist in Recovery from Shocks/Crisis

The desk review identified a lack of formal and informal safety nets within Nigeria to help families cope when shocks occur. Despite movements toward a national social protection strategy, the extremely poor and vulnerable populations have very limited formal social safety nets (Holmes et al. 2012). Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS) data from 2012/2013 found that less than 3 percent of the population accessed social safety nets at the time of the assessment, mostly for food aid (received by 1.6 percent of respondents) (Nigeria Bureau of Statistics 2014). Current social protection efforts are scattered and are focused on areas where emergency food shortages are occurring. When shocks happen, regardless of their regularity, no safety nets or mechanisms—governmental, traditional, or communal—are in place to mitigate or reduce potential and realized risk. To deal with shocks, most respondents sought additional sources of income, took on loans, or drew on assets and/or ate less often, ate less nutritious meals, or smaller meals. As shown in Table 9, a few respondents resorted to selling their animals or their productive assets, and looked for other alternatives to cope. A significant percentage of respondents in Kebbi opted to engage their children in child labor (20 percent), but this was less likely in the other locations.

Objective 3: A Well-Nourished Population, Especially Women and Children

An informant from the Kebbi ADP described the situation as “Most often you find people with what is required at hand, but its utilization is very low. It is an issue of coming in to tell people to eat what they have (rather than selling it). You’ll find that people raise a lot of poultry, which gives meat and eggs, you’ll find many groundnuts and many soybeans – all of these are high protein value crops. We must come in and tell them good recipes to make with their food.”

Improvements in nutrition rely on nutrition-sensitive interventions and approaches, but also on nutrition-specific ones. Our desk review identified poor maternal nutrition and health, particularly among very young women; poor access to health services, especially in northern states; poor IYCF; and frequent illness as drivers of malnutrition. Our fieldwork collected quantitative and qualitative data related to dietary diversity, care practices for women and children, health care provision and utilization, and WASH. We also explored stakeholders’ perceptions of nutrition and the different causes of malnutrition between states.

Lack of Dietary Diversity

Interviews with national-level experts all pointed to the monotonous diet consumed by small-scale producer households as a main reason for poor nutritional status. The Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) did not report on household dietary diversity score (HDDS) or the minimum dietary diversity for women (MDD-W), two key indicators for the GFSS. Many informants stated that most people do not consume a variety of food because of a lack of knowledge and because they follow traditional food consumption habits. Our household survey provided us the data to compute HDDS and MDD-W. However, we did not collect data on knowledge and awareness or monitor dietary intake over an extended period. It is worth noting that SPRING’s data collection was in the second half of September, the beginning of the main harvest season in most of the country; therefore, it is likely that our results, shown in Table 10, captured above average dietary diversity and it may not represent the year-round situation.

Table 10. HDDS and MDD-W by State

| Kebbi | Niger | Benue | Cross River | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household dietary diversity score (out of 12 food groups) | 6.54 | 7.22 | 7.01 | 7.64 |

| Minimum dietary diversity—women (%) | 56 | 53 | 57 | 54 |

Different numbers of food groups are used to calculate HDDS and MDD-W because the scores are used for different purposes. The HDDS is a proxy for household-level access to calories, which is one dimension of household food security. The difference between the lowest average score in Kebbi and the highest in Cross River is slightly more than one food group, indicating that sample households in Kebbi have a lower level of food security. Because there are no established cut-off points for number of food groups to indicate adequate dietary diversity for the HDDS, looking at the percentage of households consuming individual food groups is another important analytical and monitoring strategy (FAO and FHI 360 2016). Table 11 shows that household consumption of certain food groups is low across most categories, especially eggs and fruits; and, to some extent, the meat, poultry, and offal group (lowest in Benue). Low consumption of certain food groups is more state specific and includes roots and tubers in Kebbi, fruits in Niger, fish in Kebbi (percentage of households is less than half that in Cross River), and milk and dairy products in Benue (percentage of households is less than half that in Kebbi).

Table 11. Household Consumption of HDDS Standard Groups by State (percentage of households)

| Food Groups | HDDS Standard Groups | Kebbi | Niger | Benue | Cross River |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cereals | 98 | 97 | 89 | 78 |

| 2 | Root and tubers | 8 | 36 | 86 | 87 |

| 3 | Vegetables | 100 | 97 | 100 | 100 |

| 4 | Fruits | 18 | 3 | 16 | 24 |

| 5 | Meat, poultry, offal | 31 | 39 | 23 | 34 |

| 6 | Eggs | 4 | 3 | 5 | 12 |

| 7 | Fish and seafood | 42 | 72 | 65 | 86 |

| 8 | Pulses/legumes/nuts | 81 | 92 | 85 | 61 |

| 9 | Milk and milk products | 46 | 31 | 7 | 21 |

| 10 | Oil/fats | 79 | 97 | 93 | 98 |

| 11 | Sugar/honey | 31 | 58 | 34 | 67 |

| 12 | Miscellaneous | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 |

A higher MDD-W percentage means that a higher percentage of women are likely to have more adequate micronutrient intakes. Our data (see Table 12) showed that, in all four states, slightly more than half the women with children under 2 met the MDD, indicating that almost half did not have adequate micronutrient intake at the best time of the year. The intake of eggs and other fruits is limited across all states, and the intake of some food groups among women in certain states is low—such as nuts, seeds, and dairy in Benue; dark green leafy vegetables in Niger; and, to some extent, meat, poultry, and fish in Kebbi. Dietary diversity indicators do not indicate the nuances of intra-household food distribution, especially the quantity and the quality of the foods allotted to the different members of the household.

Table 12. Women’s Consumption of MDD-W Standard Groups by State (percentage of women)

| Food Group | MDD-W Standard Groups | Kebbi | Niger | Benue | Cross River |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Grains, white roots and tubers, and plantains | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99 |

| 2 | Pulses (beans, peas, and lentils) | 65 | 68 | 63 | 45 |

| 3 | Nuts and seeds | 39 | 76 | 7 | 60 |

| 4 | Dairy | 45 | 26 | 7 | 22 |

| 5 | Meat, poultry, and fish | 64 | 85 | 80 | 90 |

| 6 | Eggs | 6 | 6 | 4 | 16 |

| 7 | Dark green leafy vegetables | 74 | 12 | 47 | 42 |

| 8 | Other vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables | 85 | 97 | 93 | 100 |

| 9 | Other vegetables | 74 | 82 | 91 | 71 |

| 10 | Other fruits | 10 | 3 | 17 | 27 |

Sub-Optimal Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices

Breastfeeding

Table 13 consolidates findings from the survey on IYCF indicators. Consistent with the literature reviewed, our survey results show that the early breastfeeding initiation rate is lowest in Kebbi (27 percent) compared to the other states; the highest rate is in Cross River (75 percent). The percentage of newborns given prelacteal feeds is two to three times higher in Kebbi and Niger than in Benue and Cross River. A higher percentage of children in Benue and Cross River received colostrum without prelacteal feed, with Cross River having the best combined results. Exclusive breastfeeding prevalence among our sample is higher than what is reported in DHS data, but our sample size for this indicator across the states is small (10

Giving water to infants is a widespread practice, as shown in earlier reviews. The commonly cited reasons are religious practice and traditional belief, particularly in Kebbi. Many mothers indicated that husbands and grandmothers of the children instructed them to feed water to infants, saying it is too hot to not give babies water. Respondents also cited traditional beliefs as the primary reason children receive foods other than breastmilk before 6 months of age, but our fieldwork did not have the scope to explore these beliefs in detail.

Complementary feeding

A monotonous diet is often cited as a determinant of poor nutrition among young children; however, our findings suggest that a more nuanced examination is needed. Of the 318 households with at least one child less than two years old, surveyed across all four states, more than two-thirds of children age 6–23 months received a diverse diet per the MDD indicator definition. Dietary diversity is the summary statistics that captures the “proportion of children 6–23 months of age who receive foods from four or more food groups—out of a total of seven groups.” Because the four or more groups could be any four of the seven groups, we looked into the consumption of the several nutrient-rich food groups, particularly dairy, flesh, eggs, and vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables. We found that percentages of children consuming these food groups are still low, particularly for eggs, vitamin A-rich foods, flesh foods, and, to a lesser extent, dairy products and legumes/nuts.

In addition, barely half the children in our sample, regardless of breastfeeding status, meet the minimum meal frequency, a proxy indicator for energy intake from foods other than milk. This finding suggests that the children who were fed infrequently consumed an inadequate quantity of foods.

Table 13. Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding Indicators by State

| Indicator | Kebbi | Niger | Benue | Cross River |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early initiation of breastfeeding (%) | 25 | 38 | 34 | 75 |

| Colostrum was fed to the children (%) | 78 | 47 | 53 | 80 |

| Prelacteal feeding was given to children (%) | 71 | 59 | 21 | 30 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding (percentage of infants 0–5 months of age who are fed exclusively with breast milk during the previous day) (%) | 58 | 40 | 50 | 17 |

| Minimum dietary diversity (6–23 months) (%) | 96 | 75 | 79 | 67 |

| Grains, roots, tubers | 91 | 75 | 73 | 65 |

| Legumes and nuts | 54 | 33 | 37 | 11 |

| Dairy products | 42 | 33 | 12 | 32 |

| Flesh foods | 27 | 25 | 19 | 15 |

| Eggs | 10 | 4 | 2 | 28 |

| Vitamin-A rich fruits and veg | 3 | 25 | 29 | 8 |

| Other fruits and veg | 60 | 25 | 42 | 15 |

| Minimum meal frequency (6–23 months breastfed) (%) | 47 | 55 | 39 | 38 |

| Minimum meal frequency (6–23 months non-breastfed) (%) ^ | 21 | 50 | 53 | 52 |

| Consumption of iron-rich or iron-fortified foods (%) | 27 | 25 | 19 | 15 |

Findings on influencers of maternal and child care practices

Our survey results showed that different people, in different states, influence mothers when they make breastfeeding-related decisions (see Table 14). For sources of advice on complementary feeding, our data also showed different patterns in different states (see Table 15). In general, a husband’s opinion matters in all states, but particularly in the North and Central regions (Kebbi and Niger); while women in the South and Central (Benue and Cross River) rely more on themselves, their mothers, and health workers. Child feeding practices, overall, could improve, as reflected by the fact that most caregivers reported they would reduce the amount fed to children during illness (ranging from 78 percent in Niger to 98 percent in Kebbi: data is not in tables).

Table 14. Who Do Mothers Listen to Most about Breastfeeding-Related Decisions?

| State (n) | Self | Husband | Own mother | MIL | Health Workers | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kebbi (89) | 12 | 23 | 11 | 20 | 4 | 14 |

| Niger (33) | 2 | 14 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| Benue (66) | 18 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 1 |

| Cross River (93) | 12 | 7 | 25 | 7 | 37 | 0 |

Table 15. Who Do You Listen to Most When Making Decisions Related to How to Feed Your Child (6–23 months)?

| State (n) | Self | Husband | Own mother | MIL | Health Workers | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kebbi (81) | 6 | 40 | 11 | 10 | 2 | 10 |

| Niger (31) | 4 | 14 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Benue (67) | 20 | 21 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 2 |

| Cross River (89) | 16 | 19 | 25 | 2 | 21 | 1 |

Our survey showed major differences in the main caretaker of mothers during the perinatal period (see Table 16). In Kebbi, women rely almost equally on co-wives and mothers-in-law. The mother-in-law is the most important in both Niger and Benue, followed by their own mothers in Benue and others in Niger. However, women in Cross River rely more on their mother, followed by husbands, health workers, and then mothers-in-law.

Table 16. Who Is the Primary Caretaker of a Mother Immediately Before and Shortly after She Gives Birth?

| State (n) | Self | Husband | Own mother | MIL | Health Workers | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kebbi (81) | 0 | 4 | 11 | 21 | 9 | 126 |

| Niger (31) | 2 | 6 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 9 |

| Benue (67) | 1 | 6 | 19 | 22 | 4 | 6 |

| Cross River (89) | 5 | 15 | 40 | 12 | 14 | 5 |

Recently, the Federal Ministry of Health issued a social and behavior change communication (SBCC) strategy for IYCF (FMOH 2017). The strategy summarizes the behavioral analysis for IYCF; it also specifies the practices to be promoted, the objectives, innovations (with a focus on religious leaders), and mobilization processes (including seven groups of IYCF stakeholders). Although our surveys did not identify religious leaders as influencers of IYCF decisions, our key informants consistently referred to them as influencers in their communities. The IYCF strategy also describes roles and responsibilities of various levels of government and partners.

Public Health Services Not Equipped To Address Malnutrition

The SPRING desk review reported that the use of health services for antenatal care and delivery is low, particularly in Kebbi. The review listed various reasons, including limited capacity of personnel in the facilities to provide services; social norms preventing male workers from serving women; and a preference for traditional care providers. The fieldwork confirmed these factors, and found that people are not motivated to use government facilities because of the cost and the time spent on transportation to/from a facility. There is also the tradeoff between going to primary health care facilities versus the patent medicine stores, which are typically in or around the neighborhood. These findings indicate a low demand for facility-based health care.

SPRING visited 22 health facilities and found all were poorly staffed and stocked, often missing essential drugs and micronutrient supplements or oral rehydration salts. SPRING observed that the community health extension workers (CHEWs), who are in charge of these facilities, had limited or no resources to provide the 10 core nutrition interventions.5 Although the CHEWs we spoke to could describe nutrition assessment and treatment protocols, indicating they had received training, based on our observations, children were not routinely assessed for acute malnutrition or given nutrition counseling and other services. CHEWs reported a lack of job aids—counseling cards, illustrations, decision trees, written protocols, manuals, etc.—and little supervision or refresher training to do nutrition counseling. CHEWs shared their frustration in the interviews that the mothers often do not follow medical recommendations. KIIs with higher-level stakeholders revealed that because of the current placement procedures and salary situations, many CHEWs do not reside in their catchment areas and do not have means (transportation or travel allowances) to perform outreach functions; they also lack motivation.

Our KIIs at the national and LGA levels found that environmental health assistants (EHAs), placed at some health facilities, who do clinical work without training. This is typical in states where there are inadequate CHEWs or other health professionals, but more EHA are trained than the communities can absorb. EHAs are a type of extension worker originally intended to work in the communities to monitor and enforce personal, household, and environmental hygiene and sanitation, and to help prevent people from falling ill. The outreach function of EHAs has also diminished over time because of the similar transportation and motivation issues as the CHEWs. We also learned that the Primary Health Care under One Roof (PHCUOR) initiative exists in some states to consolidate all public health care (immunization, nutrition, etc.) programs under a state Primary Health Care (PHC) board. Currently, the job descriptions of the nutritionists are somewhat confusing because some fall under the state the Ministry of Health (MOH) and others under the state Primary Health Care Development Agency (PHCDA).

The coexistence of high levels of chronic and acute malnutrition makes nutrition problems both a crisis and an emergency in Nigeria. The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation reports that in 2016, alone, a little more than 250,000 children received treatment for severe acute malnutrition in 11 Nigerian states. This represents an enormous burden to the health infrastructure. Chronic malnutrition often goes unnoticed because it is not as obvious or alarming as severe and acute malnutrition or other symptomatic illnesses. Per statements made by key informants at national and community levels, this results in the neglect of chronic malnutrition. Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) is only operational in select areas (Kebbi), and findings from the desk review show that only about one-third of children with severe acute malnutrition access treatment. SPRING found that donor-supported projects enabled the government to include a budget line in 2017 for implementing CMAM in three LGAs—N200 million for purchase and local distribution of ready-to-use therapeutic foods (RUTF), food demonstrations, community volunteers’ motivation, procurement of drugs and data tools. The scalability and the sustainability of these initiatives are unclear. A government key informant also warned that turning to CMAM programming without investing in the prevention and restoration of mild and moderate malnutrition is like “trying to mop a wet floor while leaving the water tap on.”

Poor WASH Practices

Diarrhea and other illnesses are important contributors to acute and chronic malnutrition, and the 2015 National Nutrition and Health Survey found that 45 percent of children under 5 had diarrhea in the past two weeks. Overall, the WASH sector in Nigeria is in critical condition and requires immediate action, especially for poor, rural households: fewer than 30 percent of poor Nigerians have access to improved water and 34 percent of the rural population must travel at least two hours roundtrip to find a functioning improved water source (World Bank Group 2017). Inadequate WASH increases the risk of diarrhea and environmental enteropathy, which can lead to a reduced absorption of nutrients. SPRING’s household survey collected information on a few WASH indicators. Table 17 summarizes the WASH environment observations collected during the team community transect walks and the data from household surveys.

Table 17. WASH Findings

| WASH Element | Observations |

|---|---|

| Water source | Open dug wells are the most common source of water for all survey households in Kebbi (75 percent) and Benue (85 percent); borehole is most common in Niger (60 percent), and river/stream in Cross River (60 percent). |

| Collecting water responsibilities | Of all who fetch water, women (45 percent) and children (50 percent) together share the burden in Kebbi, with sporadic help from husbands. In Benue, women fetch water in more than 90 percent of households surveyed. Women also fetch water in most households in Niger (about 75 percent) and Cross River (about 65 percent). Husbands and children help (about 10 percent each ) and other women in the family (about 15 percent) also help in Cross River; only children and other women help in Niger (10 percent each). |

| Distance to water source | Most households in Kebbi (95 percent) and most households in Niger (75 percent) and Benue (85 percent) travel <20 minutes to their main water source; in Cross River, more than half of households surveyed travel either 20–40 minutes (30 percent) or more (25 percent) one way to the main water source. |

| Water treatment | More than two-thirds of households surveyed do not purify water. Half of households in Benue treat water; 80 percent of households do not do anything in Niger and Cross River. Of households that treat water, the most common method is to “strain with cloth” in Kebbi, “filter and strain with cloth” in Benue, “let settle” in Niger, and “boil and settle” in Cross River. |

| Toilet facility | Pit latrines are the most common form of toilet for households surveyed in Kebbi and Benue (about 70 percent and 65 percent), bush/field in Niger and Cross River (about 65 percent and 50 percent), indicating a great challenge of open defecation, which is acknowledged particularly widely in Cross River in the KIIs. |

| Hand washing | Our findings confirmed that almost all households (95–100 percent) surveyed own soap, yet washing hands with soap is not widely practiced, ranging from 3 percent in Kebbi, to 30 percent, 40 percent, and 45 percent in Niger, Benue, and Cross River, respectively. SPRING was unable to ascertain the barriers to handwashing with soap. |

| Storage of agricultural inputs | Most households we surveyed stored production chemicals inside human dwellings, 65 percent in Cross River, 80 percent in Benue, 90 percent in Kebbi, and 100 percent in Niger, all indicating immediate needs for behavioral change to avoid harm to health of family members. |

| Animal waste | SPRING observed animals wandering around the compounds of most households surveyed, ranging from 65 percent of households in Niger to 95 percent in Benue (80 percent in Cross River and 90 percent in Kebbi). SPRING observed animal droppings, ranging from 20 percent of households in Niger to 85 percent in Kebbi (55 percent in Benue and 60 percent in Cross River). |

Increased Gender Equity and Female Empowerment

Our fieldwork revealed that women play critical roles in the upkeep of families and communities; however, their potential to contribute to both improved nutrition and economic development is not fully realized. Many women participate in agriculture, in part, because of the out-migration of men seeking other livelihoods; some participate along the entire value chain from production to marketing. Women tend to earn less than men, although they are responsible for a range of similar agricultural tasks. Women have childbearing and childrearing functions and care for other household members, which complicates their abilities to work outside the home. In addition, to maintain the social network that they and their families rely on during crises and emergencies, they must keep up with many of the social obligations that disproportionally fall on them.

Several experts shared their insights with us on how gender affects nutrition and other human development indicators in Nigeria. Given that the Nigerian culture defines women’s primary function as the homemaker, there is a misperception that formally educating girls is a wasteful investment. However, literature has well established the association between women’s low levels of education and poor nutritional indicators overall (Martorell and Zongrone 2012). In fact, women’s low education levels have affected program outcomes. Our KIs shared that the MARKETS II project had to lower the target percentage of women beneficiaries because there were not enough eligible women farmers to participate. Similarly, the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMARD) nationwide social investment —Youth Educator in Agriculture—was unable to recruit the desired female participants because of the small number that could meet the selection criteria. KIs acknowledges that, at a broader level, a lack of education compromises women’s abilities to recognize their own rights, to critically think and make decisions, and to identify and seize opportunities, all hampering women’s empowerment.

Many key informants expressed their concern about the negative impact women’s low education level has on nutrition, as shown in the contrasting data between the northern and southern states. There is a sentiment to appeal for a frank discussion about the social norm to identify ways to improve nutrition without directly confronting the norm. KIs suggested ways to work within traditional norms to avoid direct confrontation. One strategy that stood out from our KIIs to gradually change social norms is to equip women with knowledge and skills that enable them to earn income. Empowering women this way will not only elevate their status within their own household but also within their communities. This change, in turn, will create a stronger position for women to make better nutrition and health decisions for their households and to shape local markets to better supply more nutritious foods to make up a high-quality diet.

More Effective Governance, Coordination, and Institutions

Coordination

KIs reported duplication of effort related to the nutrition coordination in the GoN. Two multi-sectoral nutrition coordination mechanisms exist, one led by the MOH and the other by the Ministry of Budget and National Planning (MB&NP). The MOH is the Scaling up Nutrition (SUN) focal point in Nigeria. MB&NP, on the other hand, was to the Ministry of Health establish the National Committee on Food and Nutrition (NCFN), which is the national focal point for nutrition policy, program planning, and coordination, as dictated by the National Policy on Food and Nutrition in Nigeria (NPFNN6). Our KIs described the common perception of these duplicate efforts as slowing progress in creating a nutrition budget line, as well as slowing adoption of NPFNN among the line ministries and the states. Our fieldwork also confirmed the lack of specific budget lines to support nutrition coordination and the lack of functioning state or LGA committee on food and nutrition.

Both mechanisms have largely overlapping membership and they compete for stakeholders’ time and resources. Several donors and implementing partners have formed a separate working group to push nutrition forward on the national policy agenda and budget discussion. Our review of the NPFNN document showed the 2007 approval of a National Council on Nutrition (NCN) led by the vice president of GoN (also chairperson of MB&NP) while NCFN is the designated technical arm of NCN, more than 10 years later the vice president inaugurated the NCN—November 22, 2017.

On September 16, 2017, Nigerian media widely covered the vice president’s inauguration of the Presidential Council on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Because nutrition is prominently featured in SDG2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture, the timing appears to be ripe to formalize the NCN.

Rollout

SPRING’s interviews with national-level stakeholders revealed other challenges causing the slow adoption of national nutrition policies. One is that the line ministries and state governments lack the technical capacity to identify actionable entry points for nutrition. For example, public agriculture research and higher education institutions are named stakeholders on the nutrition policies and they do attend meetings, but there is little understanding of how to link their work with nutrition outcomes. We learned of a few research groups and NGOs working closely with the private sector to scale up adoption of specific nutrition-sensitive technologies, such as Aflasafe—International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA)—and collapsible storage boxes and cold room storage (GAIN). However, we were unable to meet many signatory ministries on NPFNN to explore their efforts to incorporate nutrition into their institutional mandates.