Executive Summary

Introduction

Community-based promotion, counseling, and support programs are essential for improving maternal, infant, and young child nutrition (MIYCN) practices. In 2009, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Health Organization (WHO) agreed that a global, generic infant and young child feeding (IYCF) training package for community health workers was needed to complement the WHO/UNICEF Breastfeeding, Complementary Feeding and Infant and Young Child Feeding Integrated Counselling Package, which was specifically designed for facility-based health workers. In 2010, UNICEF published the first edition of the generic Community Infant and Young Child Feeding (C-IYCF) Counselling Package, which included an integrated set of training materials, counseling cards, take home brochures for mothers and caregivers, and a planning and adaptation guide. The authors updated and expanded the package in 2012, and added a supportive supervision guide.

The C-IYCF Counselling Package includes information and guidance for primary or community health workers (CHWs) and community volunteers (CVs) to support mothers, fathers, and other caregivers to optimally feed their infants and young children. The training package focuses primarily on increasing the knowledge of MIYCN practices among CHWs, CVs, and—in some cases—primary health workers; and improving their skills in group facilitation, interpersonal communication and counseling, support to mothers and caregivers, problem solving, and negotiation.

The interactive training is based on adult learning and empowering principles. It focuses on the effective use of a series of counseling cards during support groups and individual counseling sessions with pregnant women and mothers of infants and young children, fathers, and other caregivers. It also includes guidance for community mobilization and advocacy among government stakeholders and policymakers.

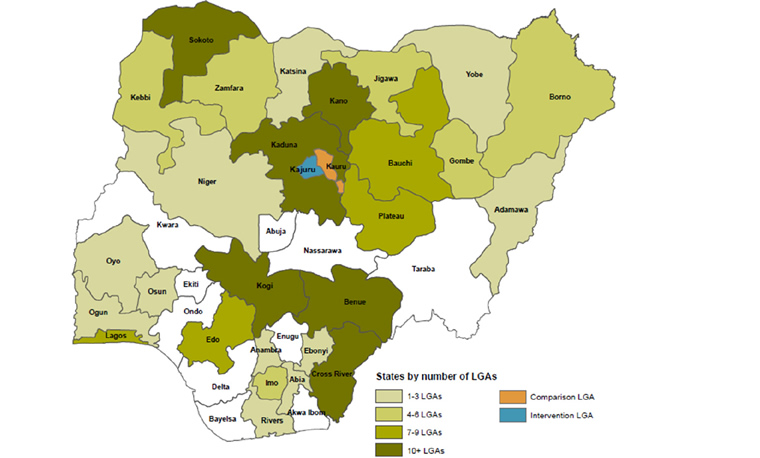

In 2013, when UNICEF surveyed 158 UNICEF country offices (UNICEF NutriDash 2014), 80 countries reported implementing IYCF programs (up from 65 reported in the 2010–2011 assessment report). Of those, 70 percent of countries (55 of 80) reported providing community-based counseling and 73 percent (58 out of 79) reported using all or part of the C-IYCF Counselling Package. However, little is known about its impact on MIYCN practices in areas where the “full” package is being implemented. Nigeria offered a unique opportunity to address this major gap in global evidence. The Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH), with support from two USAID-funded global nutrition projects—the Infant and Young Child Nutrition (IYCN) project and the Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project—made a significant investment in adapting the generic C-IYCF Counselling Package to the Nigerian context, including translating it into six local languages. Nigeria has committed to a national roll out of the counseling package, and to-date, it has been introduced in 29 out of 36 states where funding has been secured. In 2014, the FMOH, UNICEF (both UNICEF/NY and UNICEF/Nigeria), and SPRING started evaluating the C-IYCF Counselling Package in Kaduna State to assess its effectiveness when adapted to the local context and implemented at scale in one local government area (LGA), Kajuru.

Objectives

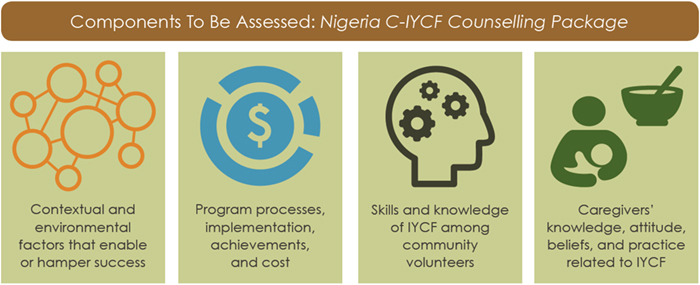

Through this evaluation, the FMOH, SPRING, and UNICEF will assess the effectiveness of the C-IYCF Counselling Package in changing knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices when adapted to the local context and implemented at scale in Kaduna State, Nigeria.

Methods

SPRING is evaluating the package using a mixed methods pre/post design with a comparison group. We are assessing the enabling environment, social support, and scale-up readiness. Health workers and CVs are assessing the knowledge and attitudes around IYCF, as well as the satisfaction with the C-IYCF Counselling Package training. In addition, we are conducting maternal and anthropometry surveys among pregnant women and mothers/caregivers of children under 2 years. Finally, we are carefully tracking the costs of implementation.

Locations

Data are being collected at the federal, state, LGA, and health facility levels. The maternal and anthropometry surveys are being conducted in one intervention LGA, Kajuru, and one comparison LGA, Kauru, both in Kaduna State.

Timeline

Both quantitative and qualitative baseline data were collected between December 2014 and June 2015. A midterm assessment of implementation processes and progress was conducted at the end of March 2016. Cost implications will be assessed in late 2016. Finally, starting in January 2017, interviews and surveys similar to those conducted during the baseline will be conducted after 18 months of implementation.

Findings

Enabling Environment

To assess the supportiveness of the enabling environment for the C-IYCF Counselling Package implementation, we evaluated four key factors: policies, resources, governance, and social norms.

Policies affect food, care, and health. For example, policies for breastfeeding—such as The National Policy on Infant and Young Child Feeding in Nigeria—offer guidance on multiple issues related to promoting breastfeeding and complementary feeding to national and local government entities and to health workers and other health authorities. While most policy documents were available at the national level, at the state level and below nutrition-related policies, reports, and tools were rarely available, even within the State Ministry of Health (SMOH). According to those interviewed, the FMOH, Federal Ministry of Social Development (FMOSD), Federal Ministry of Planning (FMOP), and Federal Ministry of Agriculture (FMOA) are actively engaged with implementing federal policies and programs related to MIYCN, and overseeing the work of state and local offices. However, nothing indicated that they were fully aware of the national policies; routinely exposed to; or involved in reviewing national, state, or local data related to MIYCN. Therefore, these key offices and their respective agents may not be fully updated on progress or areas for improvement in MIYCN practices throughout Nigeria.

Governance—participation, accountability, and voice—also impacts a country’s progress toward improved MIYCN and nutrition, in general. According to the Fifth Report on the World Nutrition Situation by the United Nations Standing Committee on Nutrition, addressing malnutrition requires effective governance systems (ACC/SCN 2004). An important starting point for good governance and management is the agenda-setting or prioritization process. Interviews at the federal level found little evidence of inter-ministerial coordination for decisions related to the administration and implementation of MIYCN programs; some evidence suggests that nutrition-related programming is quite segmented, even among units within the same ministry. Furthermore, respondents explained that decisions at the state level are strongly influenced by national priorities, which are established through a silo system, further confirming the lack of multisectoral or inter-ministerial coordination and planning. Interviews also suggested limited engagement of representatives from the state, LGA, health facility, and communities in setting the nutrition agenda or planning implementation. While state offices were significantly engaged in budgeting and oversight of state policies and programs, and were active at the LGA level, nothing suggested that they were engaged at the community level.

We did not collect information on budget allocations for MIYCN. However, we will explore resources going forward. During this baseline, we found that human resources at health facilities in the intervention LGA were seriously inadequate, limiting the likelihood of supportive supervision of CVs—an important factor to ensure the quality of C-IYCF program implementation.

Social norms and support can also affect the success of any program, particularly those that involve behavior change. To empower women to adopt and maintain optimal MIYCN practices, husbands, mothers-in-law, and community leaders—including Ward Development Committee (WDC) members, as well as health facility and LGA staff—will need to support women in multiple ways. While respondents at all levels recognized the need for stronger MIYCN programming (federal, state, and LGA representatives expressed their willingness to actively support the program); health facility staff were ambivalent about their role in working with and supporting CVs, citing a lack of funding , little community engagement, and a general low regard for CVs and their role in the community. Under the objectives and design of the C-IYCF Counselling Package, CVs are trained to play a fundamental role in providing timely peer support within communities, which complements the role of facility-based providers. Therefore, social norms and perceptions of CVs are important considerations. Emphasis should be placed on highlighting the benefits of having a well-trained and supervised cadre of CVs to the whole health care system: specifically, the health of women, young children, and their families.

Knowledge of MIYCN practices, a reflection of current social norms, was reasonably good at the national, state, LGA, and facility levels. However, there was clearly room for improvement, particularly the importance of not giving any water or pap before 6 months, and continued breastfeeding for two years or longer. Knowledge of WDC members and community leaders was suboptimal. To shift social norms and increase support for those practices, they should receive training and increase their general awareness about optimal MIYCN practices.

Responses from key informants at the state, LGA, health facility, and community levels suggested that women’s decision-making ability, particularly for MIYCF practices, may be limited.

Health Facility Personnel and Authorities

Health facility personnel and authorities (HFPA) need to know about the priority MIYCN practices, understand their importance, and support the C-IYCF activities and the role of CVs. Therefore, prior to implementation, 82 HFPAs in Kajuru received a five-day training led by C-IYCF master trainers. HFPAs completed pre- and post-training tests.

For maternal nutrition, the percentage of respondents who thought that women should avoid certain foods during pregnancy decreased from 33 to 26 percent. There is no evidence base for women avoiding any particular foods during pregnancy. Furthermore, the percentage who strongly agreed that it is important for women to eat more during pregnancy increased from 27 to 64 percent. The percentage who strongly agreed that it is important for women to eat more during lactation and rest more during pregnancy and lactation also increased, although not as dramatically.

Overall, the training had a strong impact on knowledge for optimal breastfeeding practices. By the end of the training, all HFPAs were aware that breastfeeding should start within the first hour of birth, compared with 87 percent prior to training. Before the training, respondents, on average, thought that women should exclusively breastfeed for 4.6 months. By the end of the training, this figure rose to 5.3 months. Consistent with this, the percentage of HFPAs who strongly agreed with the importance of exclusive breastfeeding for six months increased by 40 percentage points—from 47 to 87 percent—and the percentage of HFPAs who strongly disagreed with giving children under 6 months of age additional water, even when the weather is very hot, increased from 39 to 83 percent. HFPAs also became more familiar with the recommendation to continue breastfeeding for a minimum of two years. Knowledge regarding lactation management (i.e., how to increase milk supply when the mother perceived insufficient milk) also improved with the training. After the training, nearly all HFPAs knew that babies should be fed as often as they want, request, or demand; and the percentage of HFPAs who were able to identify more than three early signs of hunger increased from 25 percent prior to being trained to 62 percent after the training.

Before the training, only 61 percent of HFPAs thought that children should be introduced to complementary feeding at 6 months of age. After the training, 93 percent knew this was true and 55 percent strongly agreed with the importance of doing so—up from 13 percent prior to the training. No evidence suggests that children should not eat animal-source foods until they are 1-year-old. In fact, delayed introduction to animal source foods can have negative consequences. Unfortunately, the training failed to change HFPAs’ attitude about this. Both before and after the training, less than half of respondents strongly disagreed with the statement that “Waiting until a child is 1 year old to feed him animal protein is important for his health.”

While knowledge of most MIYCN practices increased after the training, HFPAs’ perceptions of the importance of MIYCN practices were not always as high as expected after the training and before they were tasked with training and supporting CVs. For instance, even after the training, only 60 percent strongly agreed that eating more during pregnancy and during lactation is important for the health of mothers and children. Just half or less strongly agreed with the importance of a woman resting more during lactation or breastfeeding. Likewise, just a little more than half the HFPAs strongly agreed with the importance of introducing complementary foods to children when they are 6 months old. Similarly, after the training, only one-third of respondents strongly agreed that it is important to provide infants over 6 months a diverse diet.

Although not heavily emphasized during the C-IYCF trainings, basic sanitation and hygiene is increasingly recognized as an important determinant of nutritional status. After the training, nearly all HFPAs strongly agreed that it is important to wash hands with soap at critical times: before eating, before preparing food, and before feeding children. However, only 60 percent strongly agreed with the importance of keeping animals outside the living area.

Unfortunately, attitudes about women’s role in decision making were also of concern. Only a third of HFPAs strongly disagreed that men alone should make important decisions in the family, and just slightly over half strongly agreed that a mother should be able to express her opinion regarding child feeding.

Nonetheless, after training, HFPAs were very supportive of community-based MIYCN initiatives and of engaging CVs in this work. Findings suggest that the training improved HFPAs’ understanding of best practices for moderating C-IYCF support groups. However, knowledge of effective non-verbal communication and understanding the purpose of a support group needs to improve.

Community Volunteers

CVs are the heart of the C-IYCF Counselling Package strategy to improve MIYCN practices in Nigeria. As with HFPAs, an effective CV needs to have the information, skills, motivation, and self-efficacy to act. Therefore, C-IYCF master trainers, with recently trained HFPAs, trained CVs (74 men and 163 women) from Kajuru LGA during a series of three-day trainings. The average age of the community members nominated to serve as CVs was 29. Three-quarters of respondents were Christian, while the other quarter was Muslim.

Two weeks prior to being trained, and one to two weeks after the training, CVs were interviewed during orientation meetings at nearby health facilities or community meeting points. During this time, a number of key themes emerged.

CVs’ level of empowerment or confidence to conduct C-IYCF activities and advise mothers and other caregivers on MIYCN practices is critical. Indeed, the package is designed to improve skills and raise the confidence of the CVs in their ability to organize and conduct support groups and to counsel on MIYCN. A CVs’ level of education can affect her/his level of confidence and sense of empowerment (Richards 2011). Most of those nominated to serve as CVs had, at least, attended some primary school. More than half the female CVs (45-61%) and about one-third of the male CVs (30-37%) said that their partner alone made decisions about their health care and major household purchases. Fewer than half the female CVs said they controlled the resources needed to pay for fruits/vegetables, meat/animal foods, transport to the health center for themselves or their child, or medicine for themselves or their child. However, female CVs did appear to play a larger role in decisions regarding IYCF. Two-thirds of female respondents said that they alone, or with their spouse, decided when to stop breastfeeding and when to seek health care for children. When it came to what and when to feed their children, female respondents reported making the decision, usually alone. Most, but not all, the respondents reported freedom to go alone to the local market or to the homes of neighborhood friends. More than a third of female respondents said that they were not allowed to go alone to the local health center or doctor. This lack of independent mobility could present a challenge to CVs conducting support groups and home visits or attending monthly review meetings in the local health center.

CVs’ correct knowledge and positive attitudes related to MIYCN are critical to their ability to provide counseling and support in their communities. The pre-training and post-training CV survey was an opportunity to compare responses and assess the effectiveness of the trainings, and was also a measure of how prepared the nominated CVs were to begin counseling on MIYCN practices.

For CVs’ knowledge of maternal nutrition, prior to the training, when asked how much a woman should eat during pregnancy, 64 percent thought she should eat more than before becoming pregnant. After the training this increased to 96 percent and two-thirds strongly agreed that resting and eating more was important for pregnant and breastfeeding women—up from approximately one-third.

The training improved CVs’ knowledge of optimal breastfeeding practices. By the end of the training, all but one CV answered correctly that breastfeeding should begin immediately after birth. Before the training, there were clear misconceptions about the meaning of exclusive breastfeeding, and some did not understand that it meant no liquids, sugar water, or pap. By the end of the training, however, almost all CVs stated that nothing other than breastmilk should be given to an exclusively breastfed child under 6 months. In addition, after the training, almost all CVs thought that children should exclusively breastfeed for 6 months; nearly all knew that children should be breastfed for at least two years, and lactation management knowledge improved as well. Before the training, just 50 percent of the respondents could identify more than one early sign of hunger, but after the training, more than three-quarters of the CVs could do so. Last, after the training, only one-third of CVs knew that breastfeeding can delay pregnancy. This is a significant increase from 8 percent of CVs pre-training, but it still shows significant room for improvement.

Even after the training, only 40 percent of CVs answered that the optimal age to begin complementary feeding was 6 months. The remaining 60 percent thought that complementary feeding should begin after 7 months. Although there may have been some misunderstanding around the definition of months, this finding suggests a need to reinforce the importance of the timely introduction of complementary foods (i.e., when children turn 6 months old). Only one-third of CVs strongly agreed with the importance of doing so—up from 15 percent prior to the training—and only 17 percent strongly disagreed with the statement, “waiting until a child is 1 year old to feed him animal protein is important for his health.” In addition, less than one-third of CVs strongly agreed that a diverse diet is important for infants over 6 months.

Although the training did not emphasize sanitation and hygiene, knowledge and attitudes on the topic improved. Before the training, only about a quarter of respondents strongly agreed with the importance of washing hands with soap before eating, preparing food, and feeding a child, as well as keeping animals outside the living area. After the training, more than half strongly agreed with these practices. While this is a significant improvement, there is still substantial room for improvement, and a potential recommendation may be to add additional focus on these WASH-related issues in the training package and/or refresher trainings for CVs.

Not only did we see some important gains in MIYCN knowledge after the training, CVs’ perception of the importance of MIYCN practices also improved. Prior to the training, 68 percent of respondents thought there was “very much” of a need for supporting MIYCN, community-based activities supporting MIYCN, and community volunteers to do so. After the training, more than 80 percent agreed.

Unfortunately, CVs’ attitudes toward women’s role in decision making were concerning. Even after the training, a third of CVs agreed, or strongly agreed, that only men should make important decisions in the family, and only 13 percent strongly disagreed. Responses were similar for both male and female CVs.

Pregnant Women and Mothers of Children under 2 Years Old

Our baseline findings revealed that household composition is indeed similar in both Kauru (control) and Kajuru (intervention) LGAs. Roughly a quarter of residents were under 5 years old, the mean age of respondents was 26 years old, and the sexes and ages of respondents’ children are similar in both LGAs. Most households have at least one mobile phone or radio, which may be good channels for message dissemination. However, the differences in socio-economic characteristics were statistically significant. Respondents from Kajuru are predominantly Christian, with Adara as their primary language; while, in Kauru, the majority are Muslim and Hausa is the predominant language. We also noted differences between the household wealth scores: in Kajuru, 36 percent of respondents fell into the lowest two wealth quintiles, while 43 percent did so in Kauru. Consistent with this finding, 26 percent were in the highest quintile in Kajuru, but only 15 percent were in Kauru.

Both LGAs were relatively food-secure; the main causes of undernutrition were related to suboptimal child feeding practices and behavior, not to severe food insecurity. Fewer than 2 percent of respondents in both LGAs went to sleep hungry in the previous week. Similarly, fewer than 3 percent of respondents in both LGAs reported that any member of the household went to sleep hungry in the previous week.

Unfortunately, more than two-thirds of the households in both LGAs reported having either no latrine at all or an open pit. Access to toilet facilities is necessary for proper sanitation and hygiene practices.

Women’s Empowerment

Determinants of women’s empowerment, all of which were surveyed during the baseline, include educational and employment status, control of resources, participation in decision making, and mobility.

Women in Kajuru tended to have higher levels of education than women in Kauru. In Kajuru, 68 percent of respondents had some education compared to 40 percent in Kauru. While 37 percent of respondents in Kajuru had completed some or all of secondary school, only 17 percent had done so in Kauru. Women in Kajuru were also more likely to be employed than women in Kauru. While more than half of the women in Kajuru had been employed in the last 12 months and were employed at the time of the survey, fewer than half of respondents were employed in Kauru. Among those currently employed in both LGAs, more than half worked fewer than 20 hours per week. These differences in socio-economic variables between the two LGAs must be considered as we analyze findings and assess impact following the second round of data collection planned for early 2017.

Decision making is a critical element in the status of family members because it affects the allocation of resources and the distribution of roles within families. The majority of respondents agreed, or strongly agreed, that only men should make important decisions in the family; this attitude was reflected in self-reported household decision making. Almost all women reported earning less than their husbands or partners, and a third of respondents from both LGAs said their husband or partner alone decided how to spend the money she earned. Very few reported joint decision making, although the percentage that did was higher in Kajuru than in Kauru. Most respondents reported that their husbands alone decided about health care, major household purchases, and even visits to relatives. We also observed differences in decision making on MIYCN practices between the two LGAs. In Kajuru, more respondents decided when to stop breastfeeding and what to feed their children, while in Kauru it was more common for the husband to make these decisions. In both LGAs, three-quarters of respondents reported making decisions on when to feed the child. It is important to note that because major household purchases are decided by the husband, decisions about what and when to feed the child depend largely on what the husband or partner decides to purchase and when it is made available. Furthermore, a higher percentage of respondents reported that their spouse controlled the resources to pay for transportation to the health center, medicine, fruits/vegetables, and meat/animal foods. Finally, in both LGAs the respondent’s spouse alone often decided what to do when a child falls sick. These findings reflect the patriarchal nature of both communities.

Mobility is also an important aspect of empowerment, because caregivers, especially women, need to travel to attend support group meetings. Women in Kajuru reported greater freedom to travel than those from Kauru. However, almost all the women in Kajuru and Kauru were allowed to go alone to the homes of friends in the neighborhood, and the majority of respondents agreed that women should be allowed to participate in mothers’ groups.

These findings, related to women’s level of empowerment in Nigeria, are a cause for concern when it comes to promoting MIYCN practices, and they underscore the importance of involving men in C-IYCF activities and exploring ways to empower women, particularly for MIYCN.

MIYCN Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices

Maternal nutrition practices and the nutritional status of women before and during pregnancy can have a significant influence on fetal, infant, and maternal health outcomes. Inadequate nutrition during pregnancy can lead to stunting in-utero (De Onis et al. 2012). More than half the respondents could identify at least one food rich in vitamin A and at least one food rich in iron, and the majority of mothers of children under 2 in both LGAs reported receiving an iron supplement during pregnancy. However, only half of pregnant women surveyed either received or purchased an iron supplement. This lower rate among pregnant women may reflect their stage of pregnancy, and it is important to note that receiving a supplement does not guarantee that a supplement was taken. Unfortunately, only half of the respondents in both LGAs knew that women should eat more during pregnancy.

Nearly half of pregnant women surveyed reported eating more than before becoming pregnant and a third said they ate less. Surprisingly, nearly half of mothers with children under 2 years of age said they ate less during their last pregnancy than prior to becoming pregnant, and a third said that they ate more. Respondents were not asked to explain their eating practices, but they could result from a number of factors, including appetite, availability of food, or knowledge. In addition, women’s appetites can vary based on the pregnancy trimester, so women’s responses may have depended on which trimester they were recalling. Almost all the women knew they should eat more while breastfeeding. Almost all respondents agreed or strongly agreed that resting more during, compared with before, pregnancy is important for the health of mothers and children.

Women’s knowledge and practice of optimal breastfeeding practices was also low in both LGAs. Although the majority of respondents were confident or very confident that they would be able to practice early initiation of breastfeeding, only 15 percent of mothers of children under 2 in Kajuru and 7 percent in Kauru had started breastfeeding immediately. While half of respondents knew exclusive breastfeeding should be practiced for six months, more than 80 percent thought that babies under 6 months old should be given some additional liquid, particularly glucose water and pap. In addition, three-quarters felt that children should be given additional water if the weather was very hot. Only about a quarter of respondents in Kajuru, and even fewer in Kauru, strongly agreed that exclusive breastfeeding was important for children’s health; only a third intended to exclusively breastfeed their children. Therefore, it was not surprising that more than half had introduced liquids (mostly water) other than breastmilk within the first three days of delivery; within the previous 24 hours, nearly three-quarters had given their child under 6 months of age some type of food or drink besides breastmilk. Overall, 20 percent of children in Kajuru and Kauru were exclusively breastfed, and less than half of respondents knew that children should be breastfed for at least two years. Pregnant women were more likely to intend to breastfeed for two years than those who were currently breastfeeding (a quarter of pregnant women and 10 percent or less of breastfeeding mothers). Finally, less than 1 percent of respondents in Kajuru and 3 percent in Kauru breastfed their children for 22 months or more, and the mean age for stopping breastfeeding was 15 months in Kajuru and 16 months in Kauru. A woman’s decision to stop breastfeeding is usually influenced by the predominant practice in her community and her husband’s wishes. Therefore, it is important for the community to support the right practices.

Complementary feeding practices were also suboptimal, with only a third of the children in both LGAs starting to eat solid, semi-solid, or soft foods at the recommended age of 6 months. A third in Kajuru and almost a quarter in Kauru started before 6 months. Less than half of women surveyed knew the recommended age for introducing soft, semi-solid food, and most thought it was best to wait until the child was older. Introduction of complementary foods did not necessarily mean appropriate feeding, and only 11 percent of children aged 6–23 months in Kajuru, and 9 percent in Kauru, received the minimum acceptable diet.

Although food diversity increased with age, even among the oldest children—those between 18 and 23 months— only a third consumed food from at least four of the seven food groups. Less than 20 percent of respondents from both LGAs strongly agreed that a diverse diet was important for the health of the child. Only 5 percent strongly disagreed with waiting to feed children animal-source foods until they are one-year-old.

Finally, perceptions on the importance of hygiene practices were good, although these practices were not always followed. Nearly all respondents agreed that washing hands with soap before eating, preparing food, and feeding children are important for the health of mothers and children. They also agreed that it was best to keep animals outside the living area. Three-quarters reported having soap. However, when asked when or why they used soap the day of the survey or the previous day, less than 5 percent in both LGAs said it was to wash their children’s hands or their own hands, before feeding a child, or before preparing food; only 11 percent in Kajuru and 6 percent in Kauru said it was before eating. The most common reasons for using soap were for bathing, washing clothes, or washing/bathing children.

Health care utilization was also poor in both LGAs. Less than half of respondents made a pregnancy related clinical visit and more than three-quarters gave birth at home. Only 5 percent in Kajuru and 2 percent in Kauru had ever attended a support group. The vast majority of respondents had only talked about nutrition with a health worker in a facility. This emphasizes the importance of C-IYCF counseling during support groups and home visits to promote MIYCN practices and to increase demand for health services.

Nutritional Status

Nutritional status was measured among a sub-sample of women and children. In total, we assessed the nutritional status of 614 pregnant women, 752 non-pregnant mothers, and 931 children under 2. Despite apparent access to food in both LGAs, almost a quarter of the children in Kajuru and almost half in Kauru were stunted (HAZ-2 SD). Stunting or low height-for-age (stunted growth) reflects a process of failure to reach linear growth potential as a result of suboptimal health and/or nutritional conditions. Weight-for-height, a measure of wasting and an indication of acute starvation and/or severe disease, was not as high, but it was also concerning. Indeed, a prevalence exceeding 5 percent is considered alarming, given the associated increase in mortality. In Kajuru, 7 percent of children under 2 were moderately or severely wasted (WHZ-2 SD) and 13 percent were in Kauru.

Short stature ( 145 cm) is a risk factor for poor birth outcomes and obstetric complications. Among all 1,366 women measured, 7 percent in Kajuru and 8 percent in Kauru measured less than 145 centimeters. Among pregnant women, we only measured height. Among non-pregnant women, we also calculated body mass index (BMI). Seventy-nine percent in Kajuru and 66 percent in Kauru had a BMI in the normal range (18.5–24.9). Thirteen percent in Kauru had a BMI 18.5, indicating thinness or acute malnutrition.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The baseline findings indicate a supportive or enabling environment for implementing the C-IYCF Counselling Package in Kajuru, with support at all levels, prepared HFPAs and CVs, and receptive communities. There is strong support for the implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package among federal, state, local, and community leaders, but several actions need to be taken to maximize the chances of success as the program scales up. In addition, the training of 82 HFPAs and 237 CVs improved MIYCN knowledge, attitudes, and skills, but there is still substantial room for improvement across different MIYCN and counseling domains.

Following are recommendations for increasing the success of the C-IYCF counseling package implementation and scale-up:

- Ensure that stakeholders at all levels have access to, and have been sufficiently oriented in, key national- and state-level nutrition policies, guidelines, and program documents. (Ideally, new and/or updated global policy, guidelines, and program documents related to MIYCN should be made available as rapidly as possible.)

- Emphasize and actively promote the importance of women’s empowerment and autonomy regarding IYCF decisions, across levels and systems.

- Provide CVs, especially female CVs, with more support to enhance their decision-making power, agency, and mobility so they can effectively and confidently carry out their caregiving responsibilities.

- Engage husbands in learning and advocacy activities, as their support is important for the trial, adoption, and continuation of MIYCN practices, as well as their spouses’ empowerment and ability to make informed decisions about feeding and care seeking for their children.

- Identify ways to incentivize both CVs and potential participants to engage with the C-IYCF program.

- Institute a system for new and refresher courses for the CVs and HFPAs to continue maintaining MIYCN support.

- Training alone is not enough to make changes in deeply entrenched behaviors. Periodic community mobilization events and dialogues will be extremely important.

- Re-examine the C-IYCF package, including both the training and counseling tools, to reinforce concepts and behaviors that failed to adequately increase knowledge of specific MIYCN practices.

- Reinforce knowledge and use of non-verbal communication techniques among HFPAs and CVs, as well as understanding the purpose of a support group throughout implementation.

- Continue to improve MIYCN knowledge and attitudes among women and community members, especially avoiding the use of water or any other liquids during the first 6 months of life, as well as the proper timing for introducing nutritious complementary foods.

- Because open defecation creates an unhealthy environment and increased likelihood of diarrheal disease, which is associated with malnutrition in children (Ferdous et al. 2013; Asfaw et al. 2015), ensure that sanitation and hygiene practices are adequately promoted within MIYCN programming.

- During implementation and monthly review meetings with HFPAs and CVs, further explore the knowledge and attitudes related to foods that should be avoided or should be consumed during pregnancy and lactation.

- Promote the expanded availability of and/or improve access to sanitary latrines through community campaigns and C-IYCF support group activities.

- In all community activities, consider the cultural dynamics surrounding religion and language, as well as the level of women’s literacy, empowerment, decision-making power, agency, and mobility.

- Develop strategies to increase resources to support community-level MIYCN activities that also address the need for adequate infrastructure, supportive supervision, and monitoring of program implementation.

To read the full report, download the (above) file.