Many countries have acknowledged community-based infant and young child feeding (C-IYCF) promotion, counseling, and support as one of the key pillars of IYCF strategies. In 2009, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Health Organization (WHO) agreed that a global, generic IYCF training package for community health workers was needed to complement the WHO/UNICEF Breastfeeding, Complementary Feeding and Infant and Young Child Feeding Integrated Counselling training package, which was specifically designed for facility-based health workers.

UNICEF committed to leading the development of the proposed response. The UNICEF Community Infant and Young Child Feeding (C-IYCF) Counselling Package was finalized and field tested under a strategic collaboration between UNICEF/New York and the combined technical and graphics team of Nutrition Policy and Practice and the Center for Human Services, the not-for-profit affiliate of the University Research Co., LLC. The first edition of the resulting C-IYCF Counselling Package was published at the end of 2010. Subsequently, an update in 2012 added supportive supervision to the package.

The C-IYCF Counselling Package provides information and guidance for community volunteers (CV) and primary health care staff when they support mothers, fathers, and other caregivers to optimally feed their infants and young children. The package includes materials for training health workers and CVs to increase their knowledge of maternal, infant, and young child nutrition (MIYCN) practices and to improve skills in group facilitation, interpersonal communication and counseling, support to mothers and caregivers, problem solving, and negotiation. The interactive training is based on adult learning principles, and it focuses on the effective use of a series of counseling cards during support groups and individual counseling sessions with pregnant women and mothers of infants and young children. It also includes guidance for community dialogs and community events.

Given the investment in the development and dissemination of the package, the growing global interest, and the actual adaptation and/or use of elements of UNICEF’s generic C-IYCF Counselling Package in more than 70 countries, very little is known about its impact on IYCF behaviors in the countries where it has been implemented. For this reason, high-quality studies are needed to measure the impact on IYCF behavior and to provide the evidence needed to support the investment in scaling up the package.

Nigeria offers a unique opportunity to address this major gap in global evidence because the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH)—with support from two USAID-funded global nutrition projects (the Infant and Young Child Nutrition [IYCN] project and the Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally [SPRING] project)—has made a significant investment in adapting the generic C-IYCF Counselling Package to the Nigerian context, including its translation into six local languages. Nigeria has committed to a national rollout of the C-IYCF Counselling Package—currently, in 29 or of 36 Nigerian states where funding has been secured.

After consultations with both SPRING and UNICEF, the FMOH agreed to evaluate the package. The planning and design for the study began in 2014 and it was kicked off with the establishment of a partnership between SPRING, UNICEF/New York, and UNICEF/Nigeria. Since July 2015, working in collaboration, the FMOH, the Kaduna State Ministry of Health and Human Services (SMOH), UNICEF, and SPRING finalized the study protocol, completed baseline data collection, conducted trainings, and oversaw the implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Nigeria C-IYCF Counselling Package Study Objectives.

The evaluation assesses the effectiveness of the C-IYCF Counselling Package when it is implemented on a large scale and is managed by government health services, local government officials, and the SMOH. Specific objectives include assessing the environment or context of implementation; program processes, implementation achievements, and costs; CV’s counseling and communication skills and knowledge; and mothers’ and caregivers’ knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices.

To understand the first two study objectives, a rapid mid-process assessment was conducted at the end of March 2016. The assessment examined the level of support for implementing the CIYCF Counselling Package program in Kauri’s local government area (LGA). It also determined how well the State and LGA team adhered to implementation plans that had been agreed upon by all partners. We sought to identify and record any “deviations” before the package was scaled up in other LGAs and states in Nigeria. This included identifying “on the ground” lessons learned so that adjustments to the C-IYCF Counselling Package programming could be made. This report presents the objectives, approach, findings, and several recommendations from this assessment.

Approach

The Principal Investigator (PI) of the Evaluation of Nigeria’s C-IYCF Counselling Package, Dr. Rafael Pérez-Escamilla, and co-PI, Dr. Sascha Lamstein, led the assessment, travelling to Nigeria and to the Kajuru local government area (LGA), the intervention site, between March 29 and April 2. Dr. Chris Isokpunwu, evaluation co-PI and Head of Nutrition for the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH); Ms. Christine Kaligirwa, Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) Manager from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)/Abuja; Dr. Florence Oni, Nutrition Specialist from UNICEF/Kaduna; Ms. Susan Adeyemi, Study Coordinator; and Mr. Adams George Ango, the LGA Nutrition Focal Person (NFP) were part of the mission and the assessment team.

The assessment reviewed the existing data that is routinely collected as part of the implementation of the program, as well as meetings, discussions, and interviews with UNICEF; government representatives from the federal, state, and LGA levels; community volunteers (CVs); and support group participants. See appendix 1 for the agenda from the trip and a list of meetings, interviews, and observations conducted during the assessment (appendix 2). Each data collection activity is described briefly below.

- Review of existing data:

- Routine monitoring data: CVs record key information from support group meetings and home visits. They submit simple reports of these activities; health workers and/or LGA representatives compile them each month during the monthly review meetings.

- Support group observations: The Study Coordinator conducted six observations of support groups between December 2015 and March 2016.

- Satisfaction surveys: Also, between December and March 2016, the Study Coordinator conducted 19 interviews with CVs to assess their satisfaction with the C-IYCF Counselling Package training and program implementation.

- Primary data collection:

- Discussions/meetings: At the state level, the assessment team met with the Permanent Secretary and Director of Development Aids Coordination of Ministry for Budget and Planning, Director of Primary Health Care (PHC) at the Ministry for Local Government, the State Nutrition Officer (SNO), the Assistant State Nutrition Officer (ASNO), and the Health Specialist of UNICEF/Kaduna. This included a lengthy meeting with the SNO, ASNO, NFP, Study Coordinator, and UNICEF/Kaduna to review the program impact pathway (PIP) developed during the design phase and revise it to better reflect the realities on the ground and incorporate new information from the assessment (see appendix 3).

In addition, we met with five LGA representatives from the Department of PHC and attended two ward-level monthly review meetings with CVs, which were organized by health workers, health authorities, LGA representatives, and the SMOH. - Support group observations: The assessment team observed three support group sessions during the March field visit.

- Interviews: The assessment team also interviewed three CVs and eight support group participants.

- Discussions/meetings: At the state level, the assessment team met with the Permanent Secretary and Director of Development Aids Coordination of Ministry for Budget and Planning, Director of Primary Health Care (PHC) at the Ministry for Local Government, the State Nutrition Officer (SNO), the Assistant State Nutrition Officer (ASNO), and the Health Specialist of UNICEF/Kaduna. This included a lengthy meeting with the SNO, ASNO, NFP, Study Coordinator, and UNICEF/Kaduna to review the program impact pathway (PIP) developed during the design phase and revise it to better reflect the realities on the ground and incorporate new information from the assessment (see appendix 3).

Findings

Findings from this mid-process assessment were presented at the National IYCF Task Force meeting in Abuja (see the slides in appendix 4). For this report, the findings are organized by key steps in program implementation, and they reflect common themes that emerged from the review of routine monitoring data, discussions, and interviews.

Sensitization of state and LGA leaders

While federal policies can influence state policies and funding in Nigeria, ultimately, state polices are essential for effective adoption and implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package nationwide. Recognizing the important role of state and LGA leaders, significant effort has been made to gain their support and ownership of the C-IYCF Counselling Package program in Kajuru LGA. Multiple meetings were conducted at the state and LGA levels prior to implementation. Indeed, Kaduna state developed a line item for nutrition and increased the Kajuru LGA budget ceiling for nutrition from 6 to 8 million Nigerian Naira (NGN)1 per year; it considers the C-IYCF Counselling Package the flagship maternal, infant, and young child nutrition (MIYCN) program for the state.

The SNO and ASNO both assisted with monthly review meetings—traveling to Kajuru LGA one to two times per month—and they are well informed about the progress of C-IYCF Counselling Package program implementation in Kajuru LGA. UNICEF, not the state, provided the financial support. The SNO and ASNO also recognize the important role that SPRING’s full time Study Coordinator has played in Kajuru. They expressed concern that, if the C-IYCF Counselling Package were scaled up statewide, the state and LGAs would need to hire additional staff to develop and supervise the implementation.

The control of budgets is increasingly decentralized to the LGA level. Therefore, it is important for LGA policymakers to take ownership of programs in their jurisdictions. However, the current financial management skill levels are weak at the LGA level. Fortunately, the State Ministry of Local Government is developing mechanisms that will allow LGAs to better manage funds. In addition, in early 2016, the Kaduna State Ministry of Local Government and the State Ministry of Health and Human Services (SMOH), in collaboration with UNICEF/Kaduna organized a one-day retreat. The FMOH was represented at the meeting, as well as the Kaduna SMOH, Ministry for Local Government, Ministry of Budget and Planning, PHC Development Agency, and the 23 Kaduna State LGAs. One recommendation from the retreat was for each LGA to allocate a total of 9 million NGN2 per year for nutrition—500,000 NGN/month to implement the C-IYCF Counselling Package programming and 250,000 NGN/month for Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM). LGA authorities from throughout the state are committed to including nutrition in annual work plans and budgets. Kajuru LGA was one of the first LGAs to develop and submit a budget to the state for the amount recommended to implement the CIYCF Counselling Package program activities, particularly for transport and snacks for the monthly review meetings. Although the state approved the funds, the LGA has not released them. This may be due, at least in part, to the unusually high staff turnover within the LGA. It is also important to note that the amount the LGA budgeted assumes a reduction in funds—from 1,000 to 500 NGN—for the CVs and health workers to cover transportation to and from monthly review meetings.

Selection Criteria for CVs

- Willing to serve as a volunteer

- Interest in breastfeeding and child feeding and child care Interest in community service

- Able to read and write

- Of reproductive age

- Preference to parents

- Speaks the local language.

Currently, UNICEF funding sustains the implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package program in Kajuru LGA; also, it is strongly supported by the oversight provided by the Study Coordinator. For Kajuru LGA to sustain the implementation, or for other LGAs to replicate the implementation process that has been followed in Kajuru, LGAs are likely to need additional staff to cover the extra workload. Unfortunately, a number of bureaucratic hurdles must be overcome to change or increase the LGA staff—some LGA staff report to five different entities. In addition, although the Ministry for Local Government pays the salaries of civil servants at LGAs, the Ministry of Budget and Planning pays

for political appointees.

The assessment found overwhelming enthusiasm for the C-IYCF Counselling Package among Kajuru LGA staff. The Director of PHC reported that he is extremely proud of the C-IYCF Counselling Package program, and he believes it has led to major increases in MIYCN knowledge among his staff. He would like to see everyone in his department—not only those directly involved in the program—trained on C-IYCF. Department of PHC staff also recognize the need for and their responsibility for continuing to implement the C-IYCF Counselling Package program (with or without external funds). All LGA staff are engaged in the C-IYCF activities, serving as “monitors” who lead the monthly review meetings with CVs and health workers. The NFP reported spending approximately seven days per month overseeing C-IYCF Counselling Package program implementation. LGA staff also provided counseling on IYCF during routine health talks with community leaders and other community groups, such as women’s associations.

The health educator mentioned a desire to teach women about home gardening. This promising activity to increase access to healthy foods means that participants can apply what they are learning. However, scaling up home gardens will probably require a strong partnership with the agriculture extension system. The health educator noted that, currently, there is no formal collaboration with the agricultural department.

Sensitization and mobilization of ward and community leaders

At the start, ward focal people from the Ward Development Committees (WDC) were sensitized and asked to help identify community members to serve as CVs. The Study Coordinator and LGA officials screened the nominees to ensure adherence to the selection criteria and they looked for some indication that the nominees are likely to remain in Kajuru for an extended period of time. The individuals interviewed all reported that this process of nomination was successful. This was confirmed by the fact that none of the community members nominated and trained to serve as CVs dropped out by the time of the assessment, nine months after the initial training.

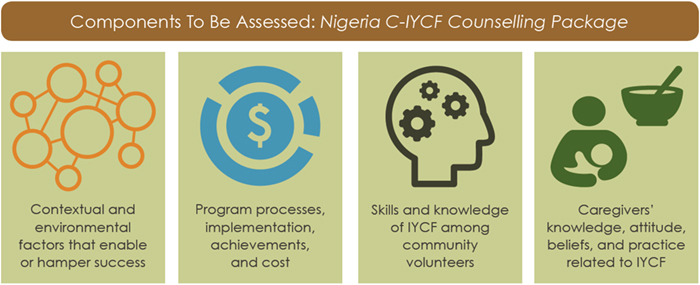

Figure 2: Proposed C-IYCF Counselling Package Training Cascade.

In June 2015, to encourage social support for MIYCN practices being promoted through the CIYCF Counselling Package, two community dialogs were conducted in each ward for representatives from the existing community groups. Four community sensitization meetings were conducted for chiefs and other community members, reaching nearly 2,400 people. The UNICEF’s Communication for Development (C4D) team conducted a second sensitization in January 2016 (six months after the first); it included a three-day event aimed at preparing existing local theater troupes to perform skits related to MIYCN practices being promoted through the C-IYCF program.

As a result, according to LGA officials, communities throughout the LGA are highly supportive of and involved in the C-IYCF Counselling Package program. Ward focal people, WDC members, and village chiefs have been actively engaged in C-IYCF activities, loaning their homes for and attending support group sessions in a number of communities. This, in turn, is likely to increase the importance that community members give to and the acceptance of the support group meetings.

Training of health workers and LGA authorities

In April 2015, nine master trainers previously trained by UNICEF in 2012 received additional training on supportive supervision. When the time came to train the health workers and LGA authorities in Kajuru, it was difficult to contract master trainers, as many are now entering retirement age. There was some confusion/disagreement about who could be considered a master trainer. For example, the SNO and ASNO were trained by SPRING, but UNICEF, initially, would not allow them to serve as master trainers of health authorities and health workers in Kajuru LGA. Ultimately, the SNO was included as a trainer; but, primarily, because master trainers were not available. A recommendation was made to revise the training cascade to include an additional state-level tier of trainers (see figure 2).

Because of the shortage of master trainers for the Kajuru trainings, the Kaduna SNO, who is not an official master trainer, was asked to help train the health workers and health authorities. This was a positive experience because she earned increased respect and ownership of the C-IYCF program activities.

In May 2015, 78 health workers and LGA authorities were trained to support the C-IYCF Counselling Package program. Initially 10 additional WDC members were included in the training; however, during the training, the organizers determined that attending a six-day training was too much to expect of WDC members.

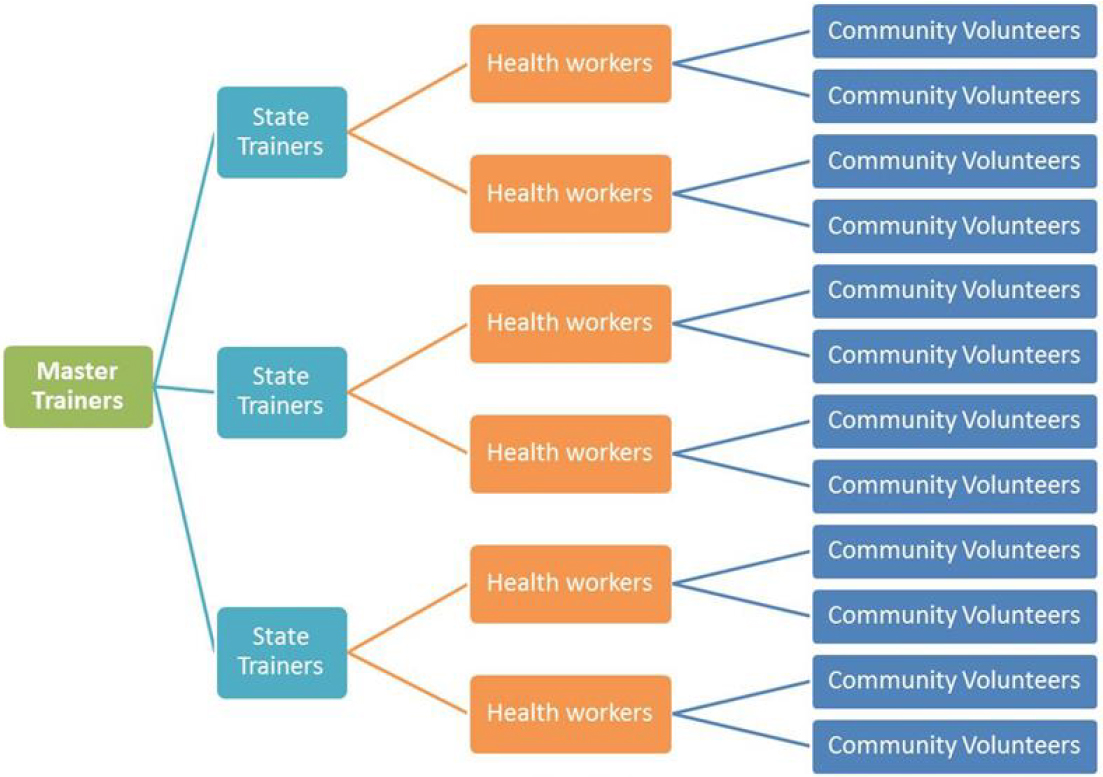

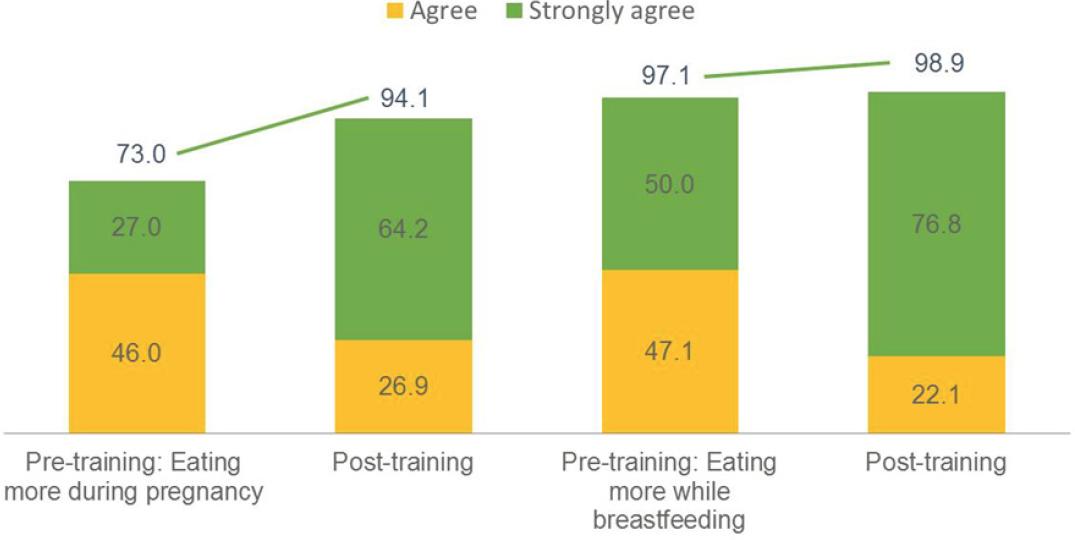

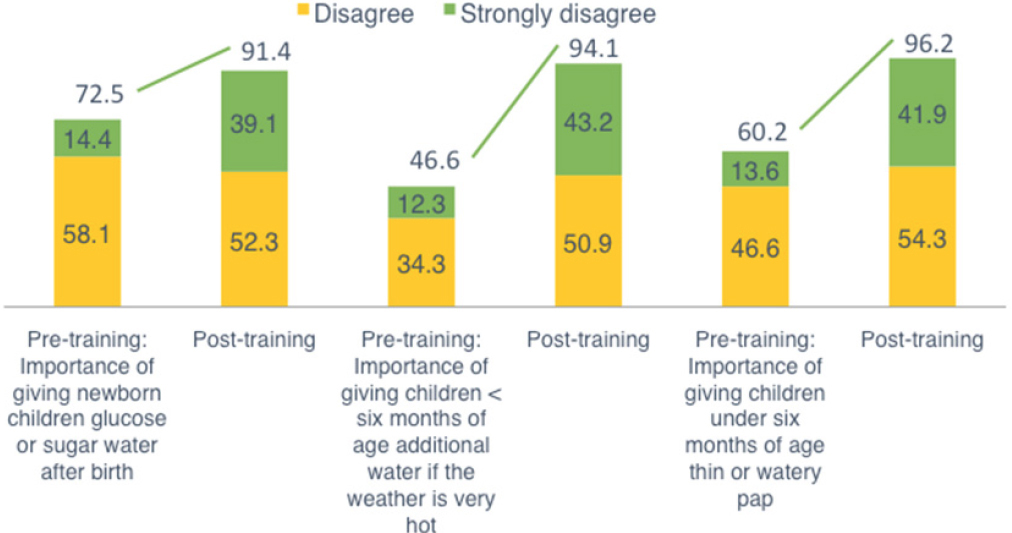

Self-administered pre- and post-training tests indicate improvements in knowledge (see figure

3) among health workers and LGA authorities. See the baseline report for a full report from these tests; however, a few key indicators are presented below.

Figure 3: Results from Pre- and Post-Training Tests among Health Workers and LGA Authorities: Breastfeeding after Delivery.

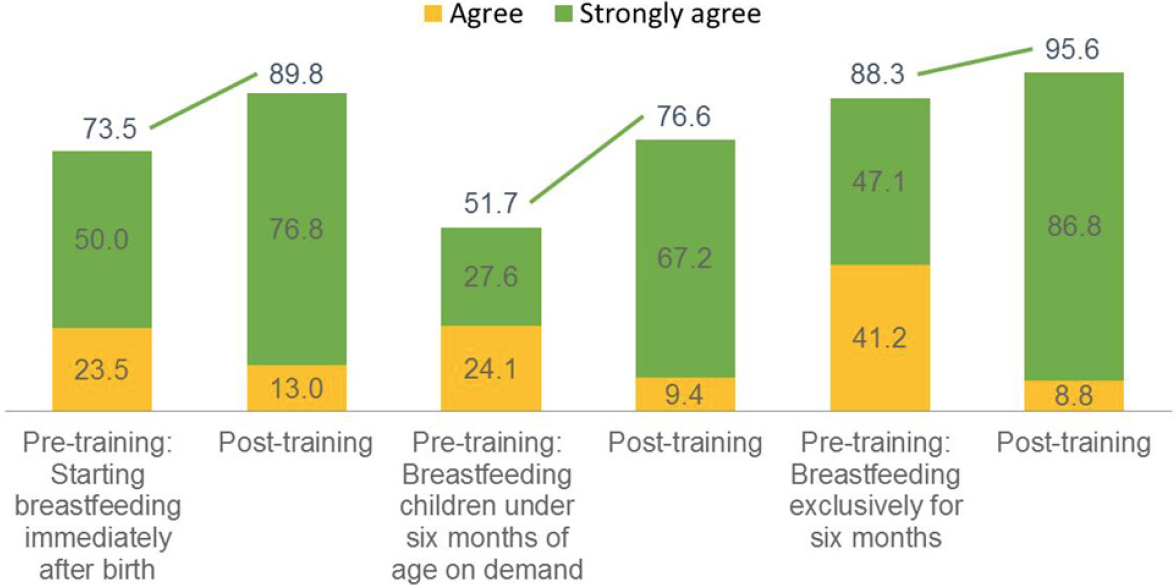

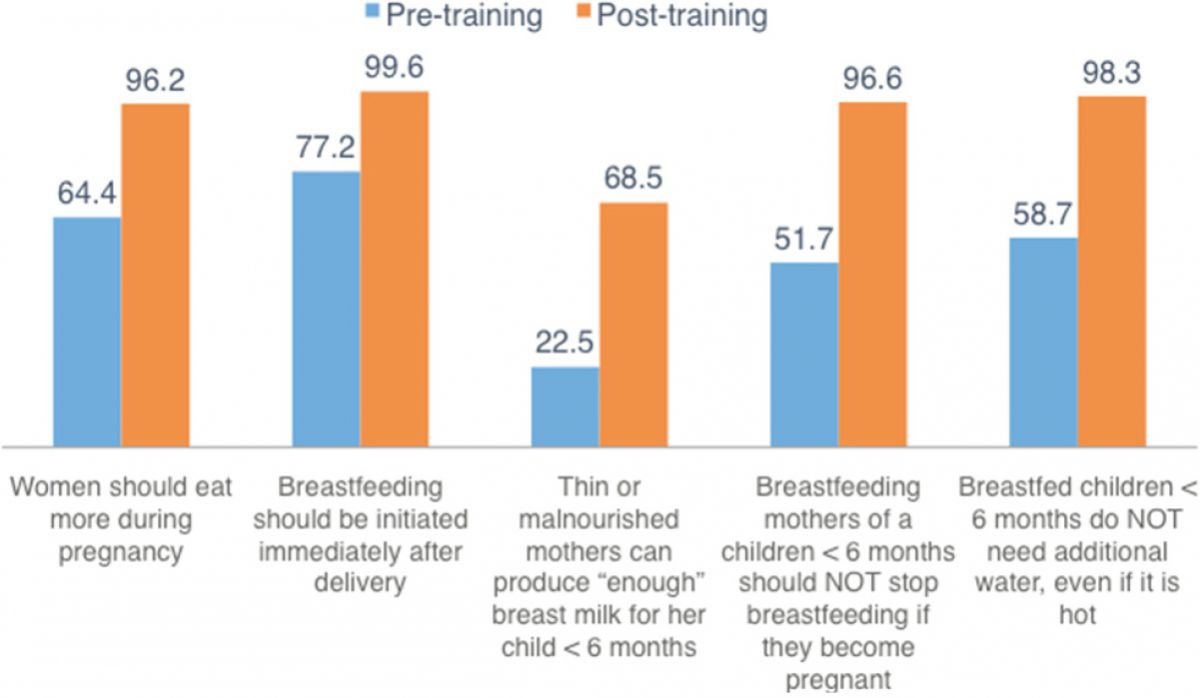

The pre- and post-training tests also asked a number of questions about beliefs and attitudes related to infant and young child feeding. The percentage who strongly agreed with the importance of key MIYCN practices for the health of the mother and/or child increased (figures 4, 5, and 6).

Figure 4. Results from Pre- and Post-Training Tests among Health Workers and LGA Authorities: Eating during Pregnancy and While Breastfeeding.

Figure 5. Results from Pre- and Post-Training Tests among Health Workers and LGA Authorities.

Figure 6. Results from Pre- and Post-Training Tests among Health Workers and LGA Authorities: Breastfeeding on Demand.

Furthermore, health workers ran the monthly review meetings observed during the mid-process assessment well. And, CVs interviewed during the assessment mentioned that health workers are helpful in answering questions.

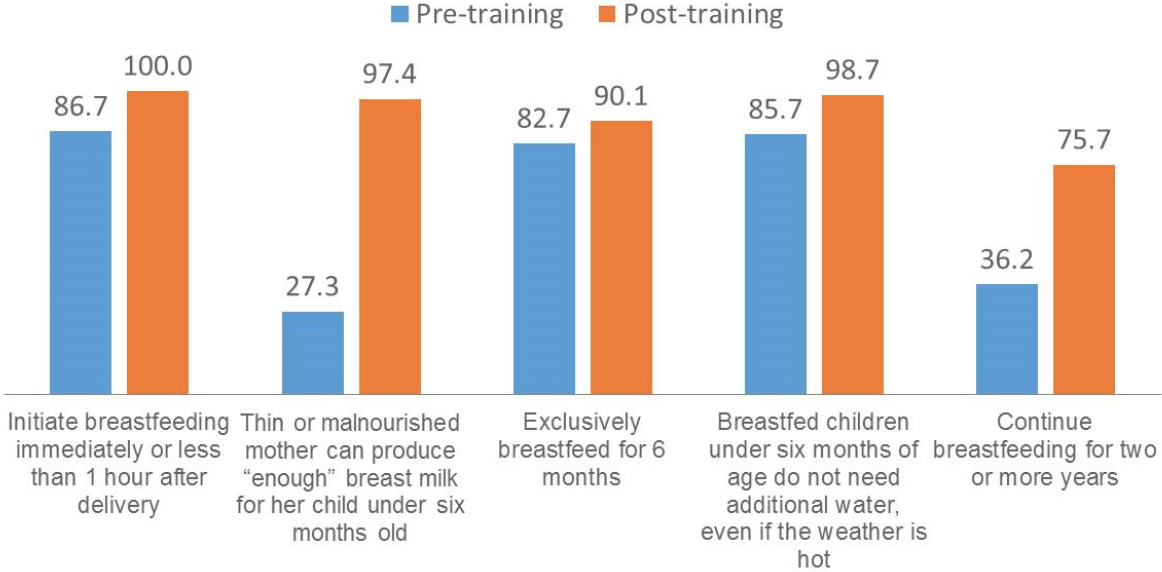

CV trainings and retention

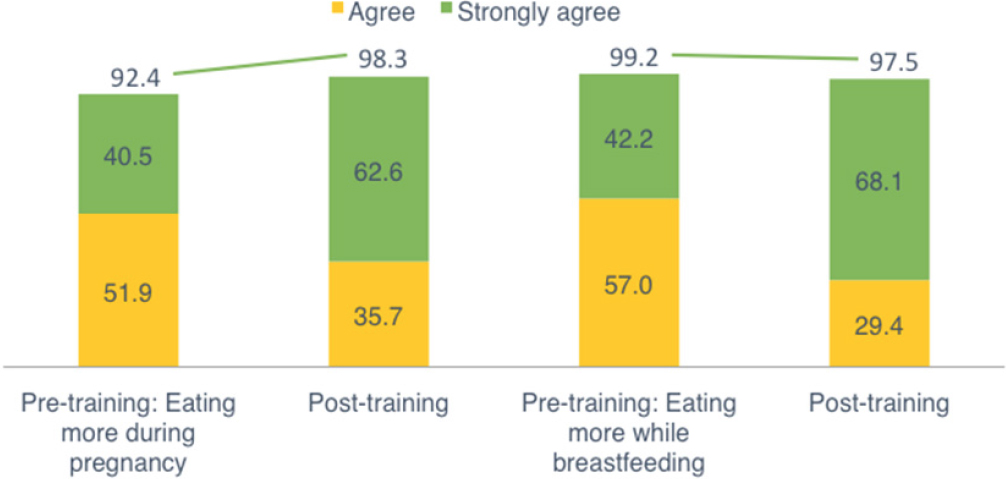

In June 2015, 238 community members were trained to serve as CVs for the C-IYCF Counselling Package program. Both CVs and participants reported that the CVs were well trained. An analysis of the pre-training survey and post-training surveys indicates improvements in both knowledge and attitudes among CVs. As indicated in figure 7, knowledge of MIYCN practices increased as a result of the training.

Figure 7. Knowledge among Community Volunteer nominees has improved.

Likewise, the percentage of CVs who strongly agree with the importance of women eating more during pregnancy and lactation increased (see figure 8), just as they disagreed about the importance or need to feed newborns sugar or glucose water after birth, water when it is hot, or pap before six months of age (figure 9).

Figure 8. Percent of CVs who strongly agree with the importance of key MIYCN practices for the health of the mother and/or child increased.

Figure 9. Percent of CVs who strongly disagree with the importance of key MIYCN practices for the health of the mother and/or child increased.

See the baseline report for a full report of the findings from these surveys.

In addition to this baseline training, UNICEF’s C4D team also led an unexpected three-day supplementary training for CVs on how to prepare, store, and package complementary foods. This training complements the C-IYCF Counselling Package training and it also responds to requests from CVs and community members. It does, however, increase the cost of implementing the C-IYCF Counsleling Package program in Kajuru LGA, which may affect the overall cost analysis for the program.

During the mid-process assessment, we found that CVs were highly satisfied with their training. The support group participants thought highly of the CVs; they noted they were well trained and open to interactions. However, during the support groups observed, CVs infrequently asked participants to share their own experiences.

As mentioned above, since the trainings in June 2015, all the trained CVs are still volunteering. This may be because, during recruitment, the CVs were clearly told that the position was unpaid, or possibly because they were motivated by seeing the impact of their efforts—changes in MIYCN practices—and the opportunity to improve their communities.

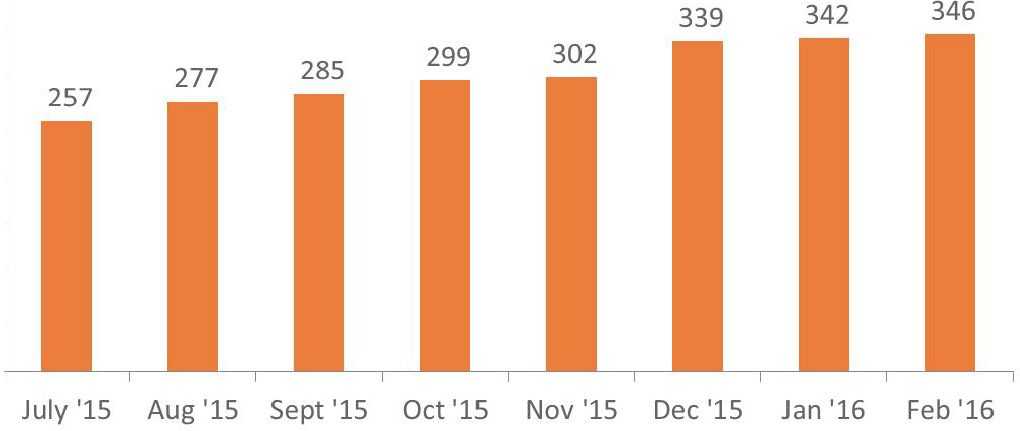

Figure 10: Support Groups Established, by Month

C-IYCF support groups and counseling

The assessment found strong evidence that the C-IYCF Counselling Package is being implemented on the ground, as planned. A review of routine monitoring data show that a total of 346 support groups have been formed, as of February 2016 (see figure 10) indicating that many CVs have established more than one group. Pregnant women, mothers (particularly those with children under 2 years old), fathers, and other family members are invited to join these groups. This is in-line with expectations.

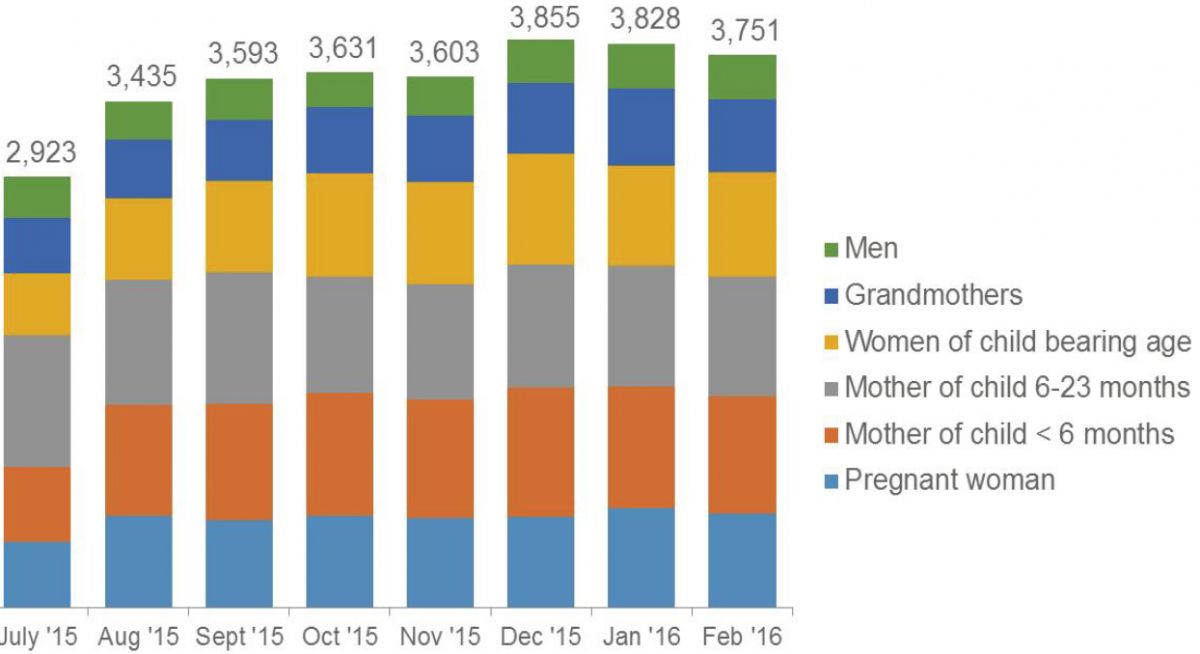

Routine data also show that people are attending the support groups (see figure 11), primarily pregnant women and mothers of young children. Both observations and interviews confirm this; however, adolescent girls, newly married girls/women, and grandmothers also attend support group meetings. As expected, men did not participate in the two support groups conducted in Muslim communities. A few men attended the support group in a Christian community. Community members explained that men in Muslim communities sometimes watch from the outskirts of the support groups.

Figure 11: Support Group Meeting Participants, by Type and Month

New people attend the support groups each month. By the end of February 2016, a total of 5,325 unique people were reached through the support groups. With an estimated 9,550 children under 2 years old and 4,213 pregnant women in Kajuru, it can be assumed that there are approximately 11,000 pregnant women and mothers of children under 2 years—many of those children are siblings and many of the pregnant women are also mothers of children under 2 years. In addition, more than 230 people have been reached through one-on-one counseling during home visits. Some of these people may have also participated in support group meetings.

Community members have also been reached through community events and dialogs, including the Theater for Development activities. Unfortunately, no one tracked the precise numbers of those reached through these activities. Support group participants also reported encouraging others to participate in support group sessions and they have shared what they learned about MIYCN with friends and family members. This type of diffusion has not been systematically tracked.

This suggests that approximately half the targeted population—those in the “1,000 days” window—was reached in Kajuru. Both CVs and support group participants, however, expressed an interest in having more community members benefit from the C-IYCF program. For this to happen, additional support groups will need to be formed.

Current CVs and/or new CVs could form new support groups. During a monthly review meeting, it was apparent that CVs had been discouraged from establishing more than two support groups. Indeed, managing three support groups would be a lot of work for a CV and they are not expected to do this. In response, they expressed an interest in cascading the training down to additional community members, but no budget is planned or in place.

When support groups were observed, it was noted that they were conducted in a relaxed manner. Participants brought their children and they interacted freely with other children during the session. Sessions lasted 45–60 minutes each, including time for recordkeeping. Participants interviewed were satisfied with the length of each session, although one participant mentioned that she would like longer sessions.

CVs used counseling cards and they frequently referred to the facilitator’s guide. The meetings were open, in an atmosphere of collegiality and respect. Participants were asked to answer questions and to express opinions. However, CVs did not always ask caregivers to share their experiences. When asked how support group topics were determined, one CV explained that she covers the topics serially, following the order in the booklet and counseling cards. While this may be the easiest way for the CV, it may not be the optimal approach, because it may not meet the specific needs of support group participants. It may be advisable to be more flexible.

Across the board, participants were very positive about the support groups, confirming that they “like everything.” They liked the topics covered and the quality of education. Many of them referred to the recommendation to avoid giving water to a breastfed baby under 6 months old as an issue they were not aware of and one that they were either practicing now or planning to practice (in the case of pregnant women). Several identified the personal hygiene topics as their favorites, but also recalled topics on breastfeeding and complementary feeding. They also appreciated how CVs led support groups—the pedagogical approach. Several participants mentioned that they felt very comfortable expressing their opinions and asking questions. They said when CVs answered questions, they could understand the answer.

For their part, CVs reported being highly satisfied with their roles and responsibilities as a CV. They enjoy sharing information, increasing knowledge, discussing MIYCN topics, as well as the respect they are given for being a trained CV. They indicated that they are motivated by the success stories related to handwashing, exclusive breastfeeding, reduced diarrhea, improved growth, and early initiation of breastfeeding to help deliver the placenta. They reported spending approximately 10 hours per month, conducting one to two support group meetings, as well as making home visits and attending the monthly review meeting in the ward.

Many of those interviewed mentioned the desire among community members for more “handson” or practical activities for applying MIYCN knowledge gained. In particular, they mentioned preparing complementary foods. They thought that these activities would motivate more community members to participate, thereby increasing the social support. As mentioned above, UNICEF’s C4D has already conducted a three-day supplementary training for all CVs on this topic.

The SNO, LGA representatives, health workers, and CVs all mentioned how some support groups have started collecting small amounts of money (100–200 NGN per person) to share with one participant each month to buy ingredients for preparing and selling complementary food, or to buy and share liquid soap.

Monitoring and support

The assessment found that the management information system is working as planned, and the assessment team accessed and used routine monitoring data to carry out their analysis. At the end of each observed support group, CVs completed the support group register. Because the CVs only recently received the new nationally harmonized forms, they were not sure which form to use to record the individual participants. This needs to be reinforced during the coming months. The monthly report forms were submitted to health workers during monthly review meetings, which are conducted in each ward and facilitated by health workers, an LGA monitor, and/or the SNO or ASNO from the SMOH. These meetings are critical for maintaining cohesion and the CVs’ quality of service. According to the CVs, this is when they usually review counseling cards, discuss challenges, and share successes. During an observed monthly review meeting, health workers and CVs performed several skits that were inspired by the C4D Theater for Development activities. The skits modeled correct, as well as incorrect behaviors, within the CVs’ support group sessions and among family members at home.

Based on observations and interviews with CVs and LGA staff, health facility staff are engaged in the C-IYCF Counselling Package program in Kajuru LGA. It appears they are promoting the CIYCF Counselling Package program and MIYCN practices, as well. Counseling cards were observed on the desk of a health worker in a facility visited during the recent field visit. According to CVs, they attend most support group sessions. Based on observations, their involvement is supportive and respectful of the role that CVs play in leading the support groups. They help to answer questions and identify women and children in need of follow-up visits by health workers. Their attendance, participation, and supervision of support groups elevates the status of CVs. Interviewed CVs appreciate the role health workers play. LGA review meetings are conducted for health workers immediately after they conduct monthly review meetings with CVs in order to aggregate data and discuss progress.

Change in knowledge, attitudes, and practices

Data on knowledge, attitudes, and practices among mothers and pregnant women was collected during the baseline survey (February–April 2015) and it will not be collected again until January 2017; however, community testimonials already indicate improved knowledge and behavior change. Support group participants interviewed reported that they have already changed their hygiene practices. Placental retention seems to be a very important issue that they now know how to address through early initiation of breastfeeding, instead of using ineffective medications and/or using high-risk procedures previously done at home and based on local beliefs. Also, the practice of giving water to breastfed children before the age of 6 months is reportedly declining, which is likely to lead to increasing rates of exclusive breastfeeding. Testimonials also report decreases in common childhood illnesses, such as diarrhea.

Enabling environment for scale up

While the focus of the mid-process assessment was on the processes of implementation, the environment or context in which the C-IYCF Counselling Package program is implemented cannot be forgotten. Indeed, the environment has significant influence, not only on behavior change, but also on implementation. The support of state, LGA, and community leaders that resulted from the sensitization activities described earlier has done much to create and strengthen an enabling environment.

In terms of the overall enabling environment for scaling up the C-IYCF Counselling Package in Nigeria, the FMOH recognizes that sub-optimal IYCF practices are widespread in Nigeria. A growing concern is the rise in obesity, which has become a large public health issue. Currently, the FMOH is very supportive of the C-IYCF Counselling Package. To address the poor rates of optimal breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices, the National Committee on Food and Nutrition of the National Planning Commission (NPC) adopted the National Plan of Action on Food and Nutrition (NPAN) in 2005. This includes the following strategies for improving care-giving capacity and improving capacity to address food and nutrition issues:

- Providing adequate nutrition and family health services in PHC centers and other health facilities within the communities.

- Creating awareness and mobilizing communities to utilize available nutrition services within PHC services.

- Creating an enabling environment for the practice of optimal breastfeeding, provision of adequate complementary foods, and other key household practices.

- Promoting nutrition education and training of caregivers, including men, at household and community levels.

- Educating and training the girl child and women because they are the majority of the caregivers at the household level.

- Improving key household practices, including adequate sanitation and safe storage of water and food.

- Promoting nutrition projects within the communities that are rehabilitative/curative.

- Promoting the provision of adequate nutrition care by community-based support groups, including agricultural extension workers and women in agriculture, among others.

- Establishing linkages with income-generating activities to enhance the resource base for caregivers.

- Increasing community-based growth monitoring programs to monitor child growth and development, as well as to detect growth faltering.

- Establishing/strengthening, coordinating, and implementing mechanisms at the national, state, and LGA levels.

To-date, the C-IYCF Counselling Package has been rolled out in 191 LGAs in Nigeria, in 30 out of 36 states—at various levels of coverage—by the FMOH, SMOH, UNICEF, and several implementing partners, including the SPRING project and the Department for International Development-funded WINNN project.

The national C-IYCF Task Force, which the FMOH organized, can play an important role in harmonizing how the C-IYCF Counselling Package is implemented in Nigeria and in promoting it nationwide. Meetings, like the one organized for government officials from Kaduna State, will play an important role in facilitating and encouraging consultation and coordination.

Discussions with key stakeholders in the country, including UNICEF, suggested that approaches to and tools for implementing the C-IYCF Counselling Package, used by the various implementing agencies, need to be harmonized so the package can be positioned as the standard of choice for all state, LGA, and ward-level service delivery programs focused on MIYCN. Implementation of the package should capitalize on and integrate with other programs involving community-based work and community volunteers, such as the Volunteer Community Mobilizers (VCM), who UNICEF engaged for the polio eradication initiatives; and the CMAM, which primarily focuses on the health facilities. UNICEF also believes that community engagement with strong state support is key for scale up. For its part, UNICEF is interested in fostering a social movement for nutrition and IYCF through social media.

Conclusions

Based on multiple sources of evidence3 and findings described above, the mid-process assessment team concluded that the implementation of the C-IYCF Counselling Package program is progressing according to plans. Not only are the activities taking place and the target coverage being reached, but all the CVs who were trained are still in the program. Through our multiple interactions with key informants at various levels of implementation, we also conclude that the process of implementing the C-IYCF Counselling Package program at scale, within an LGA, is based on an enabling environment that has fostered strong enthusiasm and a movement for change in social norms for the central role of community engagement for improving MIYCN practices.

It is clear that the Study Coordinator has been crucial for successfully implementing the program in Kajuru. However, her role has gone beyond just coordinating the study to now including extensive oversight and coordination of program activities, as well. While the successful implementation in Kajuru was the goal and the Study Coordinator deserves praise for her achievements, her role and achievements may not be replicable in every LGA—someone with similar qualifications may not be available within the government structure.

A few other areas of concern became evident to the research team and/or were mentioned during meetings, discussions, and interviews held during the mid-process assessment field trip. First, implementation remains reliant on funding from UNICEF. While the LGA budgeted funds for the C-IYCF Counselling Package program, and the state approved the budget, the LGA has not released the funds.

Second, even with the high number of CVs trained and working in Kajuru, coverage of women and children in the 1,000 days window remains at 50 percent. To change social norms and have an impact at the population level, coverage will need to be higher.

Third, men (husbands and fathers), as well as grandmothers, play an important role in promoting and permitting adoption of MIYCN practices. However, they are not being adequately reached through support groups.

Finally, CVs demonstrated improved knowledge and capacity to facilitate support groups. However, they did not ask participants to share experiences. Building on personal experience is an important aspect of adult learning and the experiential learning cycle.

Recommendations

This mid-process assessment team identified several key recommendations that should improve implementation, the chances of longer-term success of the program in Kaduna, and the replication elsewhere in Kaduna and other states in Nigeria. Regarding sustainability within Kajuru and replication elsewhere at scale—

- Transfer responsibilities to the LGA: For the program to be sustainable and scalable, each LGA needs to own and operate it, with support from the SMOH. Therefore, as is possible, responsibility for funding and oversight should be transferred to the LGA. However, transferring management to the LGA may require significant reductions in the budget for the program, possibly resulting in reduced incentives (e.g., transportation reimbursement). In turn, it may reduce the motivation for CVs. This transfer of responsibility for funding implementation will need to be carefully managed.

- Reconsider the training cascade: Reconsider the criteria for professionals qualified to train health authorities, health workers, and down the training cascade to CVs. This might mean adding a level to the training cascade that defines appropriate criteria and defines the role of state officials in training LGA health authorities and health workers.

- Stick to the PIP: Our goal for this study was to determine if this specific C-IYCF Counselling Package program is effective enough to adopt it as a model for replication globally. If additional activities are conducted in Kajuru that go beyond the PIP presented in this report, it may not be possible for other LGAs or states to replicate or scale up the entire program, in terms of cost, time, and technical expertise.

- Build on existing systems: As Nigeria looks toward replicating and scaling up the package, it will be important to build on the existing systems, such as those established for maternal and child health days, immunization campaigns, and malaria control programs.

- Strengthen partnerships: To build on the existing systems, partnerships will need to be formed across sectors and within sectors.

- Document the role of the Study Coordinator: We consider the multiple roles that the Study Coordinator has played to ensure adherence to implementation plans essential. This sentiment was echoed by many interviewed. Therefore, all that the Study Coordinator has done—supervisory visits, phone calls, and more—will need to be well documented as an element of C-IYCF Counselling Package program implementation.

Based on our assessment, we also recommend the following to improve implementation in Kajuru:

- Identify opportunities to incentivize CVs: While CVs appear motivated by the result of the C-IYCF activities, volunteering for up to 10 hours per month is a significant commitment. To sustain CVs and avoid attrition, it will be important for state and LGA officials to incentivize CVs with non-financial actions: verbal praise, awards, certificates,

or in-kind payments. - Maintain or increase supportive supervision as integral: We recommend the Study Coordinator, SNO, and/or ASNO conduct a minimum of four observations of Support Group sessions and interviews with CVs per month, in collaboration with LGA and ward leaders. Interviews suggest that these are incredibly important for improving the quality of services provided, validating the work of CVs, and motivating CVs and community members.

- Capitalize on monthly review meetings: Monthly review meetings have been effectively built into operational plans for implementing the C-IYCF Counselling Package in Kajuru. These are perfect opportunities to reinforce key messages, conduct short refresher trainings, and disseminate priorities, such as establishing new support groups (if they can) or taking more time to ask women to share their experiences (successes and challenges). If a monthly review meeting cannot be held, we recommend a quarterly review meeting.

- Reinforce importance of asking and listening to participants share their experiences: CVs currently ask participants questions to ensure comprehension. While this is an excellent pedagogical approach, a key component of adult learning is allowing the participant to consider the proposed MIYCN behaviors in terms of their own experiences. We did not observe CVs asking or listening to participants share experiences. CVs should be encouraged to do so during each session.

- Increase reach: To ensure MIYCN practices are adopted and sustained, husbands and grandmothers in C-IYCF support groups and/or other community-based activities need to increase their participation. To do so, CVs may be allowed and/or encouraged to establish additional support groups beyond the current limit of two, or additional community members could be trained to serve as CVs.

- Consider advocacy a routine activity: With the turnover of LGA leaders and, possibly, community leaders, advocacy and sensitization should be considered an on-going activity instead of one that occurs only once at the start of program implementation.

Footnotes

1 On April 27, 2016 the official exchange rate was 199.05 NGN for every US$1.00.

2 Idem.

3 Sources of evidence for this mid‐process assessment include 1) the routine monitoring data; 2) interviews with key informants from the national to the community level and UNICEF officials; 3) direct observations of support groups, followed by interviews with CVs and participants; 4) interviews with CVs and observation of support groups conducted by the Study Coordinator prior to our arrival; and 5) PIP validation meeting with LGA NFP, SNO, ASNO, Study Coordinator, and UNICEF/Kaduna Nutrition Officer.