Prior to the Ebola virus disease outbreak (EVD) outbreak in Guinea in 2014, 76.6 percent of children 6 to 59 months were anemic and 31.2 percent were stunted (DHS 2013), reflecting an already challenging context for nutrition. As part of USAID’s Ebola recovery efforts, USAID/Guinea and USAID/Washington’s Bureau for Food Security (BFS) requested that the SPRING conduct a nutrition assessment to identify key contributors to undernutrition in the post-Ebola environment with a special focus on USAID’s zone of influence, (ZOI), the Rio Tinto railroad corridor. As per guidance from USAID/Guinea and USAID/BFS, SPRING focused its fieldwork in the prefectures of Faranah and Kissidougou. The objectives of the assessment were to—

- identify key contributors to undernutrition in the ZOI, including the type and extent of social and behavioral constraints to optimal nutrition, especially that of dietary diversity and protein consumption among children and pregnant/lactating women

- document the key effects of EVD outbreak on food, agriculture, health, and nutrition services and systems that need to be considered relative to future programming

- apply assessment findings to determine best approaches for improving nutritional status in the ZOI, especially of pregnant and lactating women and children under two years of age.

The following report summarizes the findings captured over the course of the Guinea nutrition assessment conducted between July and early October 2015. SPRING first completed a desk review, then a three-week field assessment that focused on key informant interviews in Conakry, Faranah, and Kissidougou. The assessment team included a cross-disciplinary group of agriculture, food security, nutrition, and social behavior change communication (SBCC) experts. SPRING’s rapid qualitative assessment confirmed many themes uncovered through the team’s desk review and results were consistent with in-depth studies and population-based surveys. Furthermore, discussions with key informants revealed common challenges and opportunities related to agriculture, food security, health, nutrition, and SBCC.

- Key challenges: Poverty, hunger season, agricultural productivity, dietary diversity and market choices, food plate and feeding patterns, infant and young child feeding practices, hygiene and sanitation, information, and public services.

- Key opportunities: Adaptability of community members, variety of agricultural crops, growing interest in educational resources, motivation of local staff, recognition of nutritional challenges, and strength of local partners.

Given these key challenges and opportunities, SPRING recommends targeting five beneficiary groups through four focus interventions:

- Beneficiary groups: Vulnerable community members, with emphasis on the first 1,000 days and first 1,000-day households, health service providers, agriculture service providers, learning institutions, and community-based organizations.

- Focus interventions: Social behavior change communication for nutrition-sensitive agriculture, capacity building and institutional strengthening, community-based programming, and knowledge management and learning.

Introduction

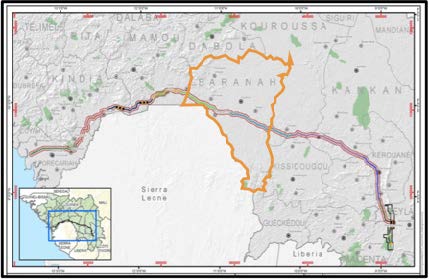

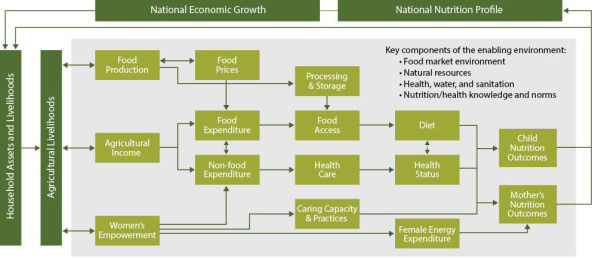

SPRING conducted a nutrition assessment for USAID/Guinea between July and early October 2015, under-post Ebola response funding provided by the Bureau for Food Security (BFS). The assessment was designed to examine the impact of the Ebola crisis on services, agricultural production, and food security in Guinea, and its relationship to high levels of undernutrition, including stunting and anemia. In response to a scope of work (SOW) shared by USAID in early July, SPRING brought nutrition, agriculture, and social and behavior change communication (SBCC) experts together to review the current context of nutrition, health and nutrition-related programming, and nutrition-sensitive agriculture in the country, with emphasis on women and children under two years of age. The results of the assessment are intended to inform the Mission on the way forward for addressing nutrition in a more integrated and systematic way, building synergies where possible between USAID’s health programming and the anticipated Feed the Future agricultural investments currently under development.

An extensive desk review was conducted in July and August, and survey tools were developed for use during the field assessment. With guidance from USAID/Guinea, the SPRING team focused its field work in September on two sub-prefectures in the region of Faranah in the anticipated USAID zone of influence (ZOI) along the Rio Tinto railroad corridor. Information about health, nutrition and agriculture programming across the country was also gathered. Based on the desk study and specific data collected during the field assessment, SPRING drafted this report summarizing key findings. A set of programmatic recommendations is also included, focused on proven or highly promising nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive agriculture interventions. Based on guidance from USAID/Guinea during in-brief and out-brief discussion, these recommendations reflect the concepts of collaboration, learning, and adaptation (CLA), presenting interventions and activities that can be implemented by SPRING and/or other USAID Feed the Future investments.

The major findings in the report are organized under the desk review and field assessment sections. The programmatic section presents proposed target audiences, alternatives for the operational ZOI, potential partners (government, donor, and implementing partners in the region), and four suggested focus interventions and illustrative activities. Contact information for key informants (both organizational and community-level); food access and dietary consumption patterns; proposed Feed the Future program indicators; and other relevant information is summarized in a series of annexes.

Based on the full range of findings and recommendations contained in this report, SPRING will work with USAID/Guinea to design and implement a two-year program under a modest complementary post-Ebola response investment. This work will provide a testing ground for nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive agriculture actions, including innovative social and behavior change activities. SPRING will share lessons learned during the program period through a specific knowledge management/knowledge sharing effort to inform the design and implementation of future USAID health, nutrition, and food security projects, as well as the anticipated Feed the Future investments.

Assessment Objectives and Methodology

The following assessment objectives and additional clarifications made by USAID/Guinea guided SPRING’s desk review and design of the field-based assessment.

Assessment Objectives of Original Statement of Work

Based on the original SOW provided by USAID/Washington, the SPRING nutrition assessment in Guinea was designed to—

- identify the key contributors to undernutrition in the ZOI, including the type and extent of social and behavioral constraints to optimal nutrition, especially that of dietary diversity and protein consumption among children and pregnant and lactating women

- document the key effects of the Ebola virus outbreak on food, agriculture, health, and nutrition services and systems that need to be considered relative to future programming

- apply assessment findings to determine best approaches for improving nutritional status in the ZOI, especially of pregnant and lactating women and children under two years of age.

Clarifications by USAID/Guinea during the Field Assessment

During the field assessment visit, the SPRING team was encouraged to reflect on and provide input to USAID/Guinea on several issues that would support the development of the Guinea Feed the Future strategy, with specific emphasis on nutrition-sensitive agriculture. SPRING has addressed the following under programmatic recommendations in the nutrition assessment report:

- key beneficiaries

- priority prefectures or sub-prefectures (to contribute to definition of the USAID/Guinea ZOI

- partnership development to enrich programming, reduce duplicative efforts, and provide opportunities to leverage resources and expertise

- key intervention areas and illustrative activities, including drivers for change

- indicators (impact, outcome, and output levels) for the USAID/Guinea Feed the Future strategy.

USAID/Guinea expressed interest in engaging in SPRING’s subsequent workplan development process. This engagement would ensure that the proposed activities reflect the Mission’s vision, and provide both collaboration and learning opportunities on a small scale that might feed into USAID/Guinea’s larger, long-term activities.

Nutrition Assessment Desk Review Methodology

In response to the original SOW, SPRING conducted an in-depth desk review, collaborated with the Leveraging Economic Opportunities (LEO) project during its Guinea assessment field work, and organized a three-week in-country assessment to inform its overall report on the current nutrition situation within Guinea. The desk review focused on quantitative population surveys, including the last Demographic and Health Survey (DHS 2013) and two Standardized Monitoring and Assessment of Relief and Transitions (SMART) surveys (2012, 2015), key government policy documents, and reports on the country’s food security and agriculture and health services. In addition to LEO, SPRING collaborated with and/or drew from the recent experiences of other USAID investments in Guinea, including a member of the Global Health team’s recent trip report, Johns Hopkins University’s Health (JHU) Communication Capacity Collaborative (HC3) project, JHPIEGO’s Maternal Child Survival Project (MCSP), MEASURE Evaluation, and the University of California Davis’ Horticulture Innovations Lab assessment.

Nutrition Assessment Fieldwork Methodology

Based on the original objectives for SPRING’s nutrition assessment, initial suggestions by SPRING’s USAID Agreement Officer’s Representative (AOR) team, and discussions during the in-brief with USAID/Guinea, a decision was made to focus the in-country work on key informant interviews in Conakry with representatives of the Ministries of Health and Agriculture, United Nations (UN) agencies, members of the national Nutrition and Food Security Cluster, and USAID implementing partners (IPs). The field assessment focused on the prefectures of Kissidougou and Faranah, within the region of Faranah. As such, the qualitative field data only relate to findings from locations visited in those two prefectures, and cannot be seen as representative for all of Guinea.

SPRING’s on-the-ground nutrition assessment was conducted in September 2015. The assessment team was led by SPRING’s senior advisor for nutrition and SBCC and supported by a SPRING project coordinator, an international agriculture and food security consultant with relevant experience in Guinea, a Guinean agriculture and food security specialist, a Guinean nutrition specialist seconded from SPRING’s partner organization Helen Keller International (HKI), and a representative from the Guinean Ministry of Agriculture (MOA). Support from two local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) working in the two target prefectures was also organized in advance of SPRING’s field visit.

SPRING’s field assessment was guided by a set of qualitative assessment tools that the project team developed prior to travel. These tools were intended to capture relevant information from a range of key informants working at the national, prefecture, and sub-prefecture (district) levels in health, agriculture, and/or food security. The tools were streamlined upon the team’s arrival in Guinea, a French translation was finalized, and local language translations were discussed during the orientation meetings with the NGO teams in Kissidougou and Faranah.

Over the first two days in Conakry, the SPRING assessment team prioritized meetings with USAID and several key informants, including representatives from the MOA, the Division of Nutrition within the Ministry of Health (MOH), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), HKI, and the JHUHC3 project. The team then conducted 10 days of fieldwork and returned to Conakry to continue meeting with key informants representing other NGOs and UN agencies. The team’s assessment schedule can be found in annex 1.

While in the field, the SPRING team divided into two groups that covered sub-prefectures within Kissidougou and Faranah. Each group initially met with community officials at the sub-prefecture and village levels to discuss the purpose of the assessment and request permission to proceed. These officials were supportive and provided valuable information and insight. Informal group discussions and in-depth interviews were held with community members, health agents, agriculture extension, and community development agents working at the village level. To the extent possible, the field visits were timed to coincide with weekly markets. In Faranah, the SPRING team met with the general director and key faculty from the national agriculture university, Institut Supérieur Agronomique et Vétérinaire de Faranah (ISAV), and the project director of Winrock’s Agriculture Education and Market Improvement Program (AEMIP). Overall, the team conducted multiple interviews in nine locations in Kissidougou and 13 locations in Faranah.

Table 1. Field Visit Locations, Meetings, and Informant Types

| Prefecture (2) | Sub-prefecture (10) | Meetings | Total number of informants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faranah | Faranah-center | Institut supérieur agronomique et vétérinaire (ISAV), market sellers, Tostan, Tindo, Winrock AEMIP | 60 |

| Banian | Community members | ||

| Beléya | Health center, village group | ||

| Nyalia | Health center | ||

| Tiro | Community leaders, health center, market sellers | ||

| Kissidougou | Kissidougou-center | APARFE, market | 124 |

| Albadaria | Community leaders, health center | ||

| Beindou | Community leaders | ||

| Manfaran | Community members, women’s group | ||

| Yendé | Community leaders, health center, local farmers, women’s group |

At the end of each day, the team convened to review discussions and findings within each sub-prefecture. These daily meetings allowed the team members to address commonalities, differences, and areas on which to focus as they moved forward with fieldwork.

Over its last week in Conakry, the team worked to compile field notes, briefed USAID, and continued to conduct key informant interviews with the Peace Corps, Guinean Government ministries, UN agencies, and IPs. Table 2 below summarizes the government and UN agencies and other institutions that SPRING included as organizational informants during the assessment.

Table 2. Organizational Informants

| Implementing Partners/INGOs | Guinea Government |

|---|---|

| Action Contre la Faim (ACF) | Ministry of Agriculture |

| Association pour la Protection, l’Amélioration des Ressources Forestières et leur Enrichissement (APARFE) | Ministry of Health, Division of Nutrition |

| Catholic Relief Services (CRS) | Ministry of Decentralization and Rural Development |

| Helen Keller International (HKI) | U.S. Government |

| Institut Supérieur Agronomique et Vétérinaire (ISAV) | United States Agency for International Development (USAID) |

| JHPIEGO, Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP) | Peace Corps |

| JHU, Health Communication Capacity Collaborative (HC3) | UN Organizations |

| Plan International | Food And Agriculture Organization (FAO) |

| Population Services International (PSI) | International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) |

| Terre des Hommes (TdH) | United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) |

| Tostan | World Food Program (WFP) |

| Winrock International, Agriculture Education and Market Innovation Program (AEMIP) | Private Sector |

| Rio Tinto |

The findings from the SPRING assessment team’s qualitative field work and key informant interviews in Guinea confirmed many issues and provided additional context-specific background to understand and further enrich the findings from the desk review.

Desk Review Findings

The desk review gave SPRING a better understanding of contextual matters, as well as national-level issues influencing nutrition, health, agriculture, and food security. This section provides a description of issues that were relevant to the SOW for the assessment and that SPRING sought to confirm through the field-based assessment conducted in-country. Where possible, references will be made to specific desk review data findings relevant to the targeted zone for the field assessment (e.g., prefectures of Kissidougou and Faranah).

Country Context

Geography

The Republic of Guinea is located in West Africa. It is bordered by Guinea Bissau to the northwest, Senegal and Mali to the north, Côte d’Ivoire and Mali to the east, Liberia and Sierra Leone to the south, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. Guinea is bordered by 300 kilometers of coastline and stretches 800 kilometers from east to west and 500 kilometers from north to south. The total area of the country is 245,857 square kilometers. Guinea’s climate is tropical and alters from a rainy to a dry season, each of which lasts about six months. This climate exposes the country to permanent flood risks and to the Harmattan desert winds from the north, as well as dry season fires, particularly in Upper Guinea. The country gives rise to several major rivers of the subregion: the Niger, Senegal, Gambia, Loffa, Konkouré, and the Kolenté Rivers. Guinea is also known as the water tower of West Africa (château d’eau in French).

The four natural zones of Guinea include Lower Guinea (Basse Guinée), Middle Guinea (Moyenne Guinée), Upper Guinea (Haute Guinée), and Forest Guinea (Guinée Forestière). Lower Guinea is a region of coastal plains that cover 18 percent of the national territory and is characterized by climate-heavy rainfall varying between 3,000 and 4,000 millimeters per year with high humidity. Middle Guinea, known as the mountains region, covers 22 percent of the country, with levels of annual rainfall between 1,500 and 2,000 millimeters per year with a semi-temperate climate. Upper Guinea is a plateau region and wooded savanna that covers 40 percent of the land area. The level of precipitation varies between 1,000 and 1,500 millimeters per year with a hot, dry climate. Forest Guinea holds a set of mountain ranges covering 20 percent of the country, and is characterized by rainfall ranging between 2,000 and 3,000 millimeters per year with a damp climate (CIA 2015).

Demographics

The Guinean population is 10,628,972 inhabitants, with an average density of about 43 inhabitants per kilometer. Based on the population growth rate there will be 14,423,741 inhabitants in 2024 (Government of Guinea 2015a). Women account for almost 52 percent of the population. The majority of the population is young (44 percent under 15 years). Life expectancy at birth is currently 58.9 years, with only 4 percent of Guineans 65 years or older. The average household size is more than six people, and the vast majority of the population (70 percent) lives in rural areas. The estimated population across the four natural regions and the special area of Conakry are divided as follows: Lower Guinea (20.4 percent); Middle Guinea (22.9 percent); Upper Guinea (19.7 percent); Forest Guinea (21.7 percent); and Conakry (15.3 percent). Adult mortality levels are virtually identical for women and men (4.9 and 4.7 deaths, respectively, per 1,000). Although the child mortality rate has decreased over the years, it remains at 10 percent (IFPRI 2014).

Socio-Economic Situation

Despite its enormous natural potential, Guinea is among the poorest countries in the world. According to the Human Development Index (HDI), Guinea currently ranks 179 of 187 countries. This ranking is relatively close to its neighbors, which range between 163 (Senegal) and 183 (Sierra Leone). Guinea’s Gini coefficient is 39.4, which is also near its neighbors with a range of 33.0 (Mali) to 41.5 (Cote d’Ivoire) (Khalid 2014). This index shows that the distribution of relative income across the country is unequal and is relatively close to the inequality of neighboring countries. The socio-economic situation in Guinea in 2012 was marked by the persistence of poverty. Data from the Enquête Légère pour l’Evaluation de la Pauvreté (ELEP) 2012 indicate that 55.2 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. Economic growth is estimated at 3.9 percent, the same level as in 2011, driven mainly by increasing agricultural production and the performance of the secondary sector of industry and services. Tax revenue as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) increased from 16.8 percent to 19.8 percent, which was fueled by increased revenues on oil products and receipts on international trade.

The financing of priority social sectors by the national budget has continued to decline over the past five years. Expenditure implemented for the sectors of health and education have decreased from 18.9 percent of the total budget in 2010 to 13.5 percent in 2011 and 10.2 percent in 2012. The share of the country’s budget allocated to health accounted for 2.4 percent of the total budget on average over the period 2010-2012. Of the health system financing within the country, 81 percent is funded domestically and 19 percent from abroad (WHO 2013). Relative to other countries in the region, the Government of Guinea’s total health expenditure as a percentage of GDP is in the median range (WHO 2013).

The country holds substantial natural resources. In addition to gold, diamonds, and considerable waterways (although not all are navigable), Guinea hosts the world’s largest reserves of bauxite and untapped high-grade iron ore (CIA 2015). Guinea’s GDP is comprised of industry (44.5 percent), services (35.3 percent), and agriculture (20.2 percent). The country’s major industries are bauxite, gold, diamonds, iron ore, light manufacturing, and agriculture processing. The country’s main exports include bauxite, gold, diamonds, coffee, fish, and agriculture products. Within the agriculture sector, Guinea’s main crops and products are rice, coffee, pineapples, mangoes, palm kernels, cocoa, cassava (manioc, tapioca), bananas, potatoes, sweet potatoes, cattle, sheep, goats, and timber. Guinea’s imports consist mainly of machinery, transport equipment, textiles, and grains. While the country’s production and transport are reliant on roadways, 90 percent of the roads within the country are unpaved (CIA 2015).

Socio-Cultural Situation

Guinea is inhabited by a range of ethnic groups. The largest is the Fulani (40 percent); the Malinké (30 percent) and Soussou (20 percent) compose the next largest percentages of the total population. Smaller ethnic groups make up the remaining 10 percent of the population. Although French is the official language of Guinea, each ethnic group has a separate language, and languages are not isolated to a given geographic region. Islam is the predominant religion of the country (85 percent), with Christianity (8 percent), and indigenous beliefs (7 percent) accounting for the rest of the population.

Of Guinea’s total population, only 30.4 percent of those over the age of 15 are able to read and write. This literacy rate is 38.1 percent for males and 22.8 percent for females. The total school life expectancy, which is measured as an individual’s years of attendance of primary through tertiary school, is nine years. The gross enrollment rate (GER) in primary school increased from 78.3 percent in 2009/2010 to 80 percent in 2010/2011 and 81 percent in 2012. The GER for girls increased from 70.1 percent to 73.5 percent in the same period. The gross completion rate is 44 percent for girls and 56 percent boys. The gross primary abandonment rate is 8 percent on average, with 13 percent of girls and 6 percent of boys not completing primary school (DSRP 2013).

Youth unemployment affects 15 percent of those who possess a secondary education; 42 percent of those who have completed vocational technical education; and nearly 61 percent of those with a university degree (DSRP 2013). Of female college graduates, 85.7 percent are unable to secure a job and 61 percent of males of the same educational level are unable to secure employment. Outside school, youth idleness and lack of occupancy affect 70 percent of those under 25, regardless of the level of education and place of residence (DSRP 2013).

Health and Nutritional Issues

The Prevalence of Disease and the Impact of Ebola

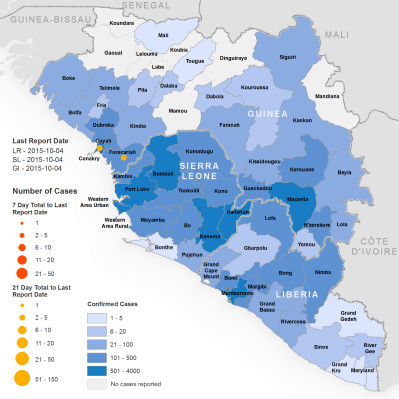

Of the major infectious diseases within Guinea, the population is at highest risk for diarrhea, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever, schistosomiasis, Lassa fever, and rabies (CIA 2015). While these diseases remain prevalent throughout the country, Ebola has altered the health and nutrition of Guineans. While the programming within the health services has shifted, the care-seeking behaviors have showed rates of decline (MEASURE 2015). With 3,800 documented Ebola cases and 2,534 documented deaths, Ebola has affected significant portions of the population within Guinea (WHO 2015a). A secondary effect of the disease is the reluctance of individuals to seek health care, which has implications for the health of the population. Both The Lancet and MEASURE Evaluation have documented a decrease in outpatient visits and overall care seeking at health facilities. As a result of this lack of preventive care-seeking, both sources cited an increase of cases of child malnutrition, malaria, and child anemia. While the Ebola outbreaks have been largely concentrated in the capital and Forest Guinea, with the highest prevalence in the prefecture of Macenta, reports of decline in health facility attendance and health care-seeking permeate the country (The Lancet 2015; MEASURE 2015).

Figure 1. Geographical Distribution of New and Total Confirmed Ebola Cases In Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone (WHO October 7, 2015)

Maternal Health and Nutritional Status

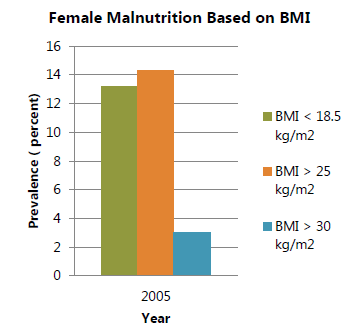

Maternal health in Guinea has improved in recent years, though several key health indicators are still lagging. Nearly half of all women of reproductive age in Guinea are anemic, with the highest rates in the Faranah and Kankan regions at 61 percent and 55 percent, respectively. Additionally, an estimated 13 percent of women give birth within 24 months of a previous birth (DHS 2013). Guinea’s high rates of maternal anemia may be in part related to poor birth spacing, as well as to the country’s high prevalence of parasites (lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminths, and trachoma are all endemic) (GAHI 2015). Anemia may also be related to a lack of access to or use of health supplies and services. Only 22-44 percent of women nationally take iron folic acid (IFA) during pregnancy; 18-29 percent take deworming medicine; 24 percent take intermittent prophylactic treatment for malaria (IPTp); and 28-39 percent sleep under insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) (DHS 2013). Less than half of all births in 2012 were attended by skilled health personnel, and slightly more than half (around 56 percent) of women had four or more antenatal care visits. Inadequate maternal nutrition also plays a key role in the overall health status of women in Guinea. Around 13-14 percent of women have low body mass index (BMI) and about the same percentage are overweight (WHO 2015c). Poor birth spacing, inadequate nutrition, and lack of access to or use of necessary health supplies and services leave pregnant women and their children at risk across the country.

Figure 2. Malnutrition in Women (WHO 2015c)

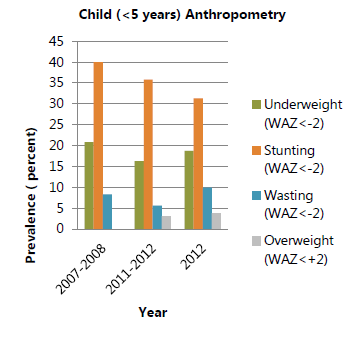

Figure 3. Malnutrition in Children (WHO 2015)

Infant and Young Child Health and Nutritional Status

Child undernutrition, both chronic and acute, is a significant problem in Guinea. An estimated 2 percent of children nationally and up to 2.4 percent in the Faranah region suffer from severe acute malnutrition (SAM). Moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) affects about 6 percent of Guinea’s children across the country (SMART 2015).

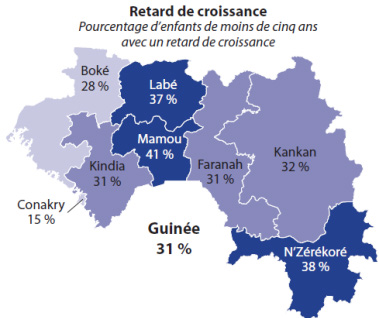

At the same time, almost a third of children are stunted (31 percent) nationally (WHO 2015c). The reported rate of stunting at birth is estimated at 9 percent, although this number is likely underestimated given that only 43 percent of children had a reported birth weight, and length is seldom measured (DHS 2013). Globally, stunting and low weight at birth are related to a number of immediate causes, including intrauterine growth retardation and/or premature birth associated with early age of first pregnancy, poor maternal diet, and/or poor birth spacing.

Other major causes of stunting among children in Guinea include poor dietary consumption (with only about 7 percent of children under two receiving a minimum acceptable diet) and the high incidence of frequent and often severe illnesses (SMART 2012).

The 2012 DHS revealed that about 16.4 percent of children ages 0-23 months experienced diarrhea in the two weeks before the survey. Immunization coverage and vitamin A supplementation is low, with vitamin A coverage at only 69 percent and only about 37 percent of children receiving their basic vaccinations (DHS 2013; SMART 2015). Only about 47 percent of households have ITNs and around 26-28 percent of children or pregnant women sleep under such nets (DHS 2013). Care seeking is often quite poor nationally: 18 percent of children received oral rehydration salts (ORS) for diarrhea; 0.2 percent received zinc for diarrhea; 41 percent were taken for treatment due to acute respiratory illness (ARI); 27 percent received anti-malarials; and 68 percent of children are dewormed each six months (SMART 2012; SMART 2015).

Figure 4. Stunting: Percentage of Children Under Five Years with Slow Growth (DHS 2013)

Inadequate treatment of illness and poor sanitation compound the problems associated with young children’s poor dietary consumption. About 21 percent of children nationally receive increased fluids and continued feeding during diarrhea and about 25 percent receive the same or more food during illness. Using a measurement of the overall minimum acceptable diet (MAD) mentioned above, 39 percent of children eat with sufficient frequency, and 16 percent receive a sufficiently diverse diet, with a mean number of food groups consumed of 1.7 (out of a recommended seven) nationally; 27 percent consume vitamin A-rich foods, and 22 percent of children 6-23 months consume iron-rich foods. Nationally, poor dietary diversity, combined with the high prevalence of malaria and other parasites contributes to 77 percent of children being anemic, and 12 percent of children receive iron to prevent or treat anemia (DHS 2013).

Table 3. Maternal and Child Health and Nutrition Indicators in Guinea

| Indicator | DHS 2005 % | SMART 2012 % | DHS 2013 % | SMART 2015 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stunting prevalence (0-5 years) | 35/td> | 35 | 31 | 25.9 |

| Wasting prevalence (0-5 years) | 9 | 5 | 10 | |

| Underweight prevalence (0-5 years) | 26 | 16 | 18 | 16.3 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding (0-5 months) | 27 | 19 | 21 | |

| Minimum acceptable diet (6-23 months)** | 6.5 | 4 | ||

| Anemia (6-59 months) | 76 | 77 | ||

| Anemia (females, 15-49 years) | 53 | 49 | ||

| Hand washing (% households with dedicated space) | 35 |

Infant and Young Child Feeding

Exclusive breastfeeding rates are among the lowest in the West Africa region, with only about 20 percent of infants under five months of age receiving only breastmilk. Early initiation of breastfeeding is more prevalent, as 76 percent of newborns nationally are breastfed within one hour of birth (DHS 2013). According to the 2013 DHS and 2015 SMART survey, only 42 percent of children 6-8 months receive complementary foods (DHS 2013; SMART 2015). Infant and young child feeding (IYCF) programming remains a huge concern for the MOH, donors, UN agencies, and implementing partners in Guinea.

Hygiene and Sanitation

Food safety and foodborne diseases pose major health problems for the population of Guinea. Of the food sold on the streets of Conakry, 81.2 percent is contaminated (Government of Guinea 2015b). According to the 2012 SMART survey, 33.4 percent of mothers wash their hands before feeding their children, and 49.3 percent of mothers wash their hands after cleaning the feces of a child. According to the 2013 DHS, 44.2 percent of households have access to improved sanitation. Nationally, 77 percent of households dispose of waste in nature. This rate is highest among rural households, with 93 percent of households in rural areas disposing of waste in natural areas. About 18 percent of the population uses a latrine (Government of Guinea 2015b).

The Ebola outbreak has resulted in distribution of handwashing stations, soap, and bleach across the country. The MEASURE Evaluation report cited substantial declines in cases of diarrhea and ARI among children (MEASURE 2015). It is unclear whether this decline is due to a decrease in visits to the health facility or increased rates of handwashing.

Diet

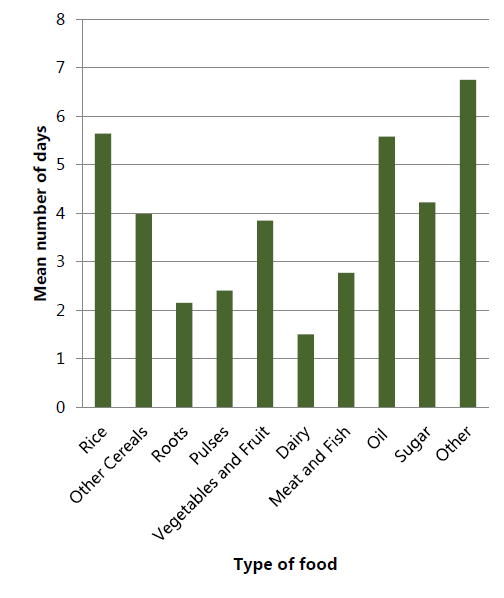

According to the SUN Movement Compendium, 2,559.8 calories per capita per day are consumed. Within these calories, 34.39 percent of an individual’s energy is derived from non-staples. Over the course of a given month, about 58 percent of a household’s food expenditure is on cereals. After cereals, oils, and fats (12 percent); meat, fish, milk production, and eggs (10 percent); and legumes (7 percent) compose a household’s expenditure on foods (Wong et al. 2015). This purchasing pattern aligns with the reported consumption of a given type of food over the past seven days, as after an “other” category, rice and oil are most frequently consumed (Wong et al. 2015).

Figure 5. Number of Days in Last Seven Days That Households Consumed Given Types of Foods (WFP 2015)

When addressing diet, nutrition, and food security, lack of knowledge of nutritious food habits is frequently mentioned as a challenge facing much of the population within Guinea. Within the Guide Pratique pour l’Alimentation du Nourrisson et du Jeune Enfant (2010), dietary practices, food preparation, and consumption are cited as main causes of poor nutritional status among children. Although the document outlines proper feeding practices and provides many recipes, there seems to be a disconnect between what is recognized as proper diet, feeding practices, and adequate consumption and what is consumed and prepared across the population. This disconnect is referenced in Guide Pratique pour l’Alimentation du Nourrisson et du Jeune Enfant (2010), included in other nutrition documents, and mentioned in other sources such as the National Emergency Food Security and Vulnerability Assessment (2012).

Through its Politique National d’Alimentation et de Nutrition (2014), the Guinean Government developed regulatory texts that focus on food fortification and food security. This food fortification includes salt iodization, the fortification of vegetable oils and flour, the creation of a Guinean alliance for food fortification, the creation of the National Food Security Council (CNSA), and the creation of the National Agency for Agricultural Development and Food Security (ANDASA) (Government of Guinea 2014b). The policy envisions “A Guinea where inhabitants are well fed” (« Une Guinée où tous les habitants sont bien nourris. »). While this phrase represents the vision for the country, the policy cites 38 areas for improvement and many wide-scale shifts to facilitate the improvement of nutrition and diets of Guineans. Such shifts mention reducing poverty, improving food and eating habits among residents, mitigating political instability, sociopolitical challenges, and the movement of populations from rural to urban areas. These sweeping recommendations reveal that significant actions are necessary to improve the diet across the country’s population.

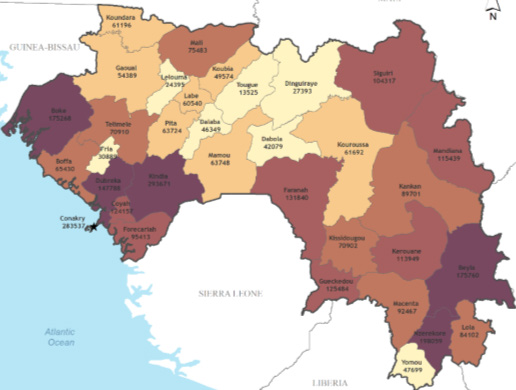

Figure 6. Food Insecurity across Guinea (GeoHive 2014)

When addressing effects of Ebola across the country, decreased income and food availability are frequently mentioned, while diets of households are rarely directly addressed. However, negative coping mechanisms of households may include a decrease in dietary quality. In its September 2015 Global Emergency Overview, ACAPS1 stated that Guinean households are exercising more negative coping strategies than households in Liberia or Sierra Leone. These negative coping strategies are a response to the compounded effects of Ebola and the lean season. These effects are estimated to be most severe in Nzérékore due to this region’s concentration of Ebola cases, and severe in Boké, Faranah, and Kankan.

Food Security

The challenge of food security within Guinea is not unique to effects of the Ebola crisis. In 2013, one million of Guinea’s 11.75 million were food insecure, and 2.85 million were borderline food insecure (Wong et al. 2015). The prevalence of food insecurity differs between rural and urban areas, with rural populations being three times as likely to be food insecure. This statistic is especially concerning due to the fact that 70 percent of Guinea’s population resides in rural areas. It is important to note that Faranah, which is within SPRING’s nutrition assessment area, has one of the highest rates of household food insecurity, with 40.6 percent of households facing food insecurity (Republic de Guinée 2015).

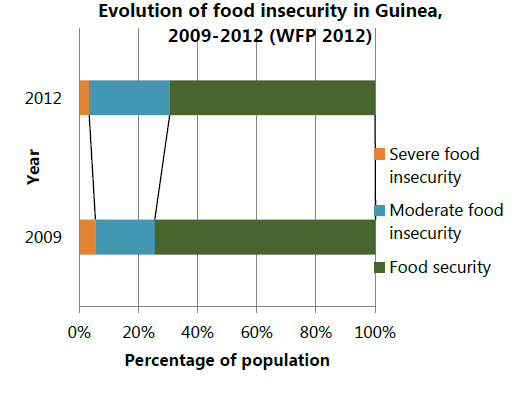

Figure 7. Evolution of Food Security in Guinea, 2009-2012 (WFP 2012)

Food insecurity is not only a problem of availability of food in Guinea. Food insecurity is also due to financial inaccessibility, the isolation of production areas, food habits and customs, the mismanagement of revenues and food stocks, conservation and inappropriate conversion, and an uneven consumption in households (Government of Guinea 2014b).

Agriculture

Guinea has a significant untapped agricultural potential with conditions suitable for growing a wide variety of agricultural products. The potential arable land is estimated at 6.2 million hectares, of which 25 percent is cultivated and less than 10 percent exploited annually. Guinean agriculture is extensive in nature and dominated by a system of traditional practices using very few yield-enhancing inputs. Family-type farms are occupied by 60 percent of the population and account for 95 percent of the land cultivated, and farm sizes are in general small, between 0.3 and 0.5 hectare. Agriculture is highly dependent on rainfall for 95 percent of the area under production. Irrigated crop production is insignificant, and among rain-fed crops, over 40 percent of the fields are located on hills or mountains and 30 percent on plains. Lowlands, while fairly abundant in some parts of the country, are poorly utilized (Government of Guinea 2010).

The main food crops are rice (42 percent); peanuts (15 percent); fonio (12 percent); corn (10 percent); cassava (9 percent); and okra, eggplant, and onion (5 percent). Livestock farming is practiced by 53 percent of households, and mainly consists of small livestock. On average, 6.2 cattle, 3.6 goats, 3.2 sheep, and 17.2 poultry are owned per household; however, this number is skewed by relatively large disparities across regions and livelihood groups, as households in Boké and Kankan have the highest average livestock numbers (Government of Guinea 2010).

Degradation of the natural resource base in Guinea makes agriculture and farming systems very vulnerable to both natural and man-made shocks. Ecological balances that might normally contribute to maintaining soil fertility have deteriorated in many areas due to land fragmentation, absence of good water management practices, and use of poor production practices. As such, a significant portion of land is facing decreased fertility and desertification. The weak productivity of the rural sector is one of the most important factors in terms of agricultural and thus economic growth. Despite efforts in the agricultural sector over the last 20 years, practices remain relatively unchanged, meaning that increased production is mainly due to increased acreage, and gains in actual productivity are very limited. The promotion of new and improved technical practices, water control measures, and the development of the land surfaces (e.g., lowland transformation in improved irrigated area) remain localized. Only 2.3 percent of plots have phytosanitary treatments, less than 8 percent of sown areas receive improved seeds, and an average of five kilograms of fertilizer is used per hectare per year (Government of Guinea 2006).

At the institutional level, Guinea is experiencing difficulties clarifying the role of the state and non-state entities (farmers’ organizations, NGOs, private sector, etc.), leading the administration to continue filling multiple functions and creating great inefficiencies in growth and development of the agricultural sector. The decentralized public structure is still too poorly equipped to advance the decentralization policy (Government of Guinea 2007).

Agricultural sector stakeholders continue to express concerns regarding the following challenges:

- Low productivity of family farms, primarily related to the decline of soil fertility, limited access to good seeds, fertilizers, farm equipment, pesticides, animal vaccines, veterinary drugs, high-quality agricultural services (research, extension, commercial/market information), reliable water control systems, an adequate financial system, and weak institutional capacities.

- Difficulty with processing, storage, and market access for agricultural products. Rural farming communities are doubly penalized by the weak state investments in education and training and by the exodus of educated people.

- Low capacity of grassroots actors due to: 1) weak organizational and professional capacity; and, 2) limited financial resources; and 3) poor organizational capacities of women and youth who are considered major contributors to agriculture.

- Insignificant agricultural export opportunities for smallholder farmers due, in part to a weak enabling environment, poor governance, and slow emergence of the private sector. It should be noted, however, that the producers’ movement is gradually growing through umbrella organizations such as commodity-specific producer unions and federations supported by a network of agricultural chambers of commerce (Government of Guinea 2007).

Agricultural Research and Learning Institutions

The Agricultural Research Institute of Guinea (IRAG) is a public scientific research institution located within but operated independent of the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock. Created April 13, 1989, the institute is still in a growth phase, building skills and consolidating initial achievements. Its mission is to contribute to the development of agriculture by conducting research relevant to the improvement of the agricultural sector in Guinea.

The network of agricultural colleges in Guinea is key to agricultural research. The ISAV in Faranah trains young professionals in agriculture, livestock, forestry, and rural engineering. It currently includes seven different faculties supported by 116 university staff members. While enrollment increases every year, a total of 1,051 students (including 135 female) attended the university during the 2014-2015 school year. Students in every faculty conduct research in preparation for their graduation thesis. Expansion plans at the university will include an increase in enrollment and improved facilities, including an 18-room lab currently under construction. In addition, the university is working on the development of two new faculties for nutrition and food sciences and environmental science.

While the university trains the next generation of agricultural expertise in Guinea, the majority of young graduates who find employment in the agricultural sector join government institutions at the central level, and very few are incentivized to take positions to support the development of the sector at the decentralized levels (e.g., [sub-] prefectural posts). Once employed in the agriculture service system the only refresher course opportunities are workshops, seminars, and short courses organized by donor-funded development programs.

Effects of Ebola on Agriculture

The Ebola virus disease crisis severely affected the country from the beginning of the outbreak, which resulted in a serious shock to the agriculture and food sectors in 2014. Given that the weather pattern and the use of inputs for production during the 2014 agricultural season were not significantly different from those during 2013, the reduction in harvest for the 2014 season can be attributed to the reduction in farm labor and associated material inputs as a result of the direct and behavioral effects of the Ebola epidemic in the country. Quantitatively, the direct impact in terms of the number people infected in relation to the size of the population of the area is very small. Much of the impact observed has been of the behavioral type due to border closures, restrictions or bans on people movement, people fleeing areas, reluctance to work in usual labor groups, and breakdown of the traditional labor-sharing system of group or teamwork (FAO and WFP 2014).

The epidemic started to spread when crops were being planted, grew during the crop maintenance period, and expanded rapidly during the critical harvesting period for the staple crops of rice, maize, and cassava. Farm operations, inputs, and the harvest were affected by the reduced availability of farm labor, and labor-associated non-labor inputs, (e.g., reduced use of material inputs such as applied quantities of fertilizer, irrigation, chemicals). Depending on use and relative impact, these changes affected crop output for the 2014 cropping season.

18 | Guinea Nutrition Assessment labor and associated material inputs as a result of the direct and behavioral effects of the Ebola epidemic in the country. Quantitatively, the direct impact in terms of the number people infected in relation to the size of the population of the area is very small. Much of the impact observed has been of the behavioral type due to border closures, restrictions or bans on people movement, people fleeing areas, reluctance to work in usual labor groups, and breakdown of the traditional labor-sharing system of group or teamwork (FAO and WFP 2014). The epidemic started to spread when crops were being planted, grew during the crop maintenance period, and expanded rapidly during the critical harvesting period for the staple crops of rice, maize, and cassava. Farm operations, inputs, and the harvest were affected by the reduced availability of farm labor, and labor-associated non-labor inputs, (e.g., reduced use of material inputs such as applied quantities of fertilizer, irrigation, chemicals). Depending on use and relative impact, these changes affected crop output for the 2014 cropping season. In summary, EVD affected agriculture during 2014 in the following ways:

- Reduced production of rice, maize, and peanuts as household members moved from affected to unaffected areas of the country, oftentimes abandoning their crops, to avoid contagion.

- Food crops, cash crops, and vegetable value chains were seriously affected by the disruption of commodity flows to areas of consumption. A sharp drop was recorded in the prices of rice, vegetable, and livestock products in the affected areas producing these commodities.

- The food security of households that depend on agricultural wages, petty trade, hunting, and the sale of hunting products, especially in the Forest Guinea, deteriorated sharply in the most affected areas (FAO and WFP 2014).

The 2015 season will, likely show some rebound from 2014 due to several incentives being made available by the government including provision of farm inputs. As long as weather conditions are favorable, crop growth and development should contribute to increased income-earning opportunities for both farm owners and poorer households that rely on opportunities for employment through farm labor. However, most households affected directly by Ebola likely will continue to face food insecurity through September 2015 on account of the residual effects of the Ebola outbreak despite various government and partner interventions—such as distribution of free food, subsidized sales, and cash-for-work programs. However, the currently observed Integrated food security Phase Classification(IPC) outcomes will likely improve to minimal levels starting in October and continue through at least December 2015 (FEWSNET 2015).

Women’s Empowerment/Gender Issues

Boys complete three more years of school (10 years) than girls (7 years) (CIA 2015). About 30 percent of Guinea’s population is literate. Men are above this average, as 38.1 percent of men over 15 years old can read and write, while women fall below at 22.8 percent. Of the women who complete secondary education, 85.7 percent are unemployed, compared to 61 percent of men of the same level of education. Seventy percent of employment in Guinea is within the agriculture, fishing, forestry, livestock, and mining sectors (CIA 2015). While women are involved in agricultural production in the preparation of land through harvest, they rarely control the resources involved (AFC 2014). Similar obstacles are experienced when attempting to access bank loans. Women and children are largely responsible for the handling of small household ruminants and poultry. However, if this work becomes especially lucrative (higher production or selling costs), men assume responsibility and management of these commodities. Over the course of a female’s life, her unequal access results in reduced means to resources and supportive structures. The Government of Guinea acknowledges inequities faced by women through its Politique Nationale Genre (2011) and outlines strategies to: 1) increase women’s access to social services; 2) respect human rights, and eliminate violence; 3) increase women’s access to and control of resources and income; and 4) introduce equitable gender practices throughout national policies.

Table 4. Land and Gender Indicators (USAID 2010)

| Indicator | Score |

|---|---|

| Women’s access to land (to acquire and own land) Range: 0-1, with 0 representing no discrimination and 1 representing discrimination | 1 |

| Women’s access to property other than land Range: 0-1, with 0 representing no discrimination and 1 representing discrimination | 0 |

| Women’s access to bank loans Range: 0-1, with 0 representing no discrimination and 1 representing discrimination | 0 |

| Percentage of female holders of agricultural land | 2% |

Health and Agriculture Services

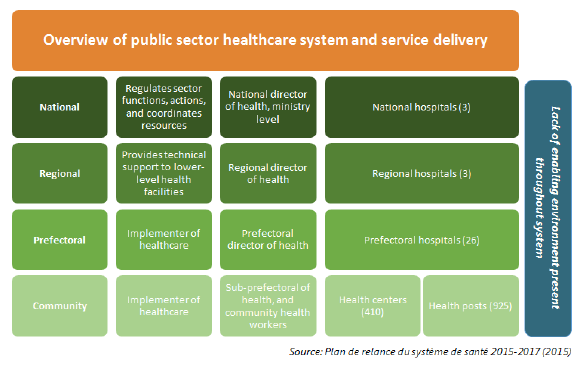

Health service facilities and health care-seeking have been significantly hindered by the Ebola outbreak (The Lancet 2015). In November 2014, 94 public health centers, which compose 23 percent of total public health centers, were closed as a result of desertion and/or death of health workers. While many public health centers have been abandoned due to other challenges within Guinea, the closure and abandonment of health centers within the country compound effects in an already minimally equipped environment.

Figure 8. Overview of Public Sector Healthcare System and Service Delivery

The Plan de Relance du Système de Santé (2015) stated that less than 10 percent of public health centers within Guinea are stocked with required equipment and have access to drinking water and electricity. In 2014, this reality worsened with the reduction of public financial flows to health districts. Although foreign aid funds specifically earmarked for health care services increased over the last few years, these finances were largely concentrated on Ebola-affected areas and were not evenly distributed throughout the country. Although this Ebola response funding has played a critical role in the country‘s ability to cope with the immediate impacts of the disease, there is an increasing recognition of the importance of rebuilding people’s trust in the formal health care system, which has been severely undermined. Engagement in routine health care services have dropped significantly, including immunization, deworming, and vitamin A supplementation programs; screening for and treatment of malaria, ARI, and diarrhea; prenatal care and institutional childbirth, etc. Only recently have funding and programming targeted improved quality of routine health care services and the issue of rebuilding trust in the health care system.2

Policies Related to Nutrition

According to the SUN Movement, Guinea created a nutrition policy in 2005 and has updated the policy over the past few years, most recently in February 2014 (SUN 2015). Specific legislation related to nutrition includes breastfeeding, flour and oil fortification, management of acute malnutrition, nutrition of children born to HIV-positive mothers, and salt iodization. Nutrition is incorporated in a number of policies and programs across the Government of Guinea:

- Agriculture Investment Plan (Plan d’Investissement Agricole).

- Health System Revitalization Plan (Plan de Relance du Système de Santé).

- National Health Development Plan (Plan National de Développement Sanitaire).

- National Health Policy (Politique National de Santé).

- National Policy of Food and Nutrition (Politique National d’Alimentation et de Nutrition).

- Poverty Reduction Strategy Document (Document de Stratégie de Réduction de la Pauvreté).

Despite these references, there is not a specific area for nutrition within the ministry’s budget, and nutrition goals or policies between ministries are not coordinated on the programmatic or financial level. Government documents, policies, and recommendations regarding nutrition, food security, and agriculture suggest that the Guinean Government recognizes the need for nutrition-specific programming and interventions. However, the lack of financing and coordination dedicated to nutrition-specific interventions indicate inconsistency between policy and implementation.

Current Nutrition Programming

Figure 9. Geographic Distribution of Food Security and Nutrition Partners

| Geographic Region | Number of food security and nutrition partners |

|---|---|

| Boké | 9 |

| Conakry | 16 |

| Faranah | 10 |

| Kankan | 13 |

| Kindia | 8 |

| Labé | 9 |

| Mamou | 7 |

| Nzérékore | 21 |

In response to the Ebola outbreak, food security and nutrition actors reformed a regularly meeting food security and nutrition cluster group. This cluster meets on a bi-monthly basis. The meetings are organized by a representative from UNICEF who sends meeting agendas, notes, and relevant meeting materials. The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) posts food security and nutrition cluster meeting resources online,3 and SPRING’s desk review was informed by this resource. This cluster has mapped nutrition program partners across Guinea, and these food security and nutrition partners include agencies of the United Nations, civil society organizations, government actors, international organizations, and national NGOs. A map of these food security and nutrition partners, and their distribution across the country, can be found in annex 2.

Many of the partners are located in more than one region within Guinea. The highest concentration of organizations is in Nzérékore, where there are 20 program partners. The second highest concentration of food security and nutrition programming is in Conakry and Kankan, where there are 11 program partners in each region. While each region has up to three food security and nutrition partners, Faranah and Mamou are the regions with the fewest separate food security and nutrition partners.

Guinea became a member of the SUN Movement in May 2013. Nutrition programming throughout Guinea focuses on prevention of severe and moderate malnutrition, the first 1,000 days and high-impact interventions, food security programs, and mass fortification. Within its summary document on Guinea, SUN notes that despite the existence of a SUN working group, there are opportunities for increased programming unification. This cohesion could be initiated through increased monitoring and evaluation and a common results framework to cross-cut all nutrition programming (SUN 2014).

Field Assessment Findings

The SPRING Nutrition Assessment included key informant interviews in Conakry, and a 10-day field assessment visit that targeted various sub-prefectures and villages in the prefectures of Kissidougou and Faranah (also referred to as the SPRING assessment area). This section provides an overview and focuses primarily on the major field assessment findings based on individual and group interviews with key informants (community members, health and agricultural sector service providers, and various development partners), and site visits to health facilities and markets, described in the methodology section of this report. The findings helped to confirm a number of issues identified during the desk review described above.

Key Challenges

The key challenges presented below focus on issues that were repeatedly mentioned as affecting economic development and improved health and/or nutrition for rural households, specifically in Kissidougou and Faranah.

Poverty

The income of the general rural population in the SPRING assessment area revolves primarily around agriculture, and to some extent livestock. The majority of rural (smallholder) households generally have limited purchasing power thus affecting their year-round access to quality and diversified foods, especially when annual household production does not cover basic family needs. Household representatives (men and women) interviewed confirmed that the annual smallholder household production of rice, the main staple throughout Guinea, does not cover the year-round food needs of the family. Agricultural commodities destined for household consumption are often sold off on the market to gain cash revenue for non-food security-related needs, such as school fees, medical care, celebrations, and emergency family events.

Figure 10. Examples of ‘Food Heaps’ as Sold on a Local Market

The isolation of some rural populations further contributes to poverty by preventing opportunities to access larger markets or engage in other income-generating activities. Most rural households live on a “day-to-day” basis and do not engage in household planning, income savings, or food conservation practices. Market vendors often reinforce or enable this way of operating by selling fixed-price “heaps” of food (see Figure 10) that are sufficient for making a basic daily sauce, which is eaten with the available staple crop (e.g., rice when available or roots and tubers during the hunger season). A number of household members (especially women) are involved in food processing and transformation practices (e.g., peanut paste, processed cassava, dried fish or okra, and néré powder [scientific name – Parkia biglobosa]),4 which are labor intensive and generally completed by hand. This kind of work increases the demand for energy and reduces time available to invest in other household tasks, including food preparation and child care or income-generating activities. Limited or no access to basic utilities (electricity, clean/potable water, fuel, etc.) or public services compounds the development difficulties experienced by rural communities and contributes to a vicious cycle of poverty.

Hunger Season

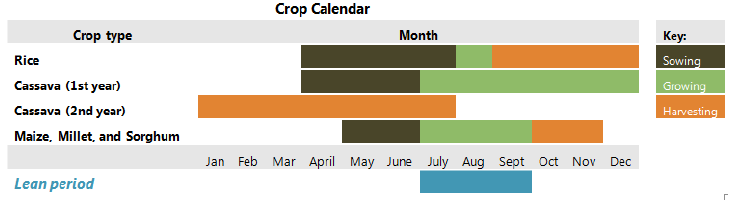

It was not surprising that virtually all informants expressed concern about the annually recurring “hunger season” that the majority of rural households face. The hunger season (also known as “lean period” or periode de soudure in French) tends to be a recurrent phenomenon throughout Guinea. Although everyone is aware of the season—generally between June and September—households seem unable to plan ahead to reduce the negative impact of this yearly phenomenon. While planning to overcome this period may not systematically occur, many informants provided insight regarding potential coping strategies. (See figure 11.)

Figure 11. Crop Calendar (FAO GIEWS 2014)

Since production volume of household staple crops (e.g., rice in the SPRING assessment area) is hardly ever sufficient to feed a family throughout the year, households have adopted a number of mechanisms to “manage” the hunger season. These include—

- income generation to increase cash revenue through non-agricultural commercial activities, sale of non-staple crops (including seasonal fruits and vegetables), and the sale of livestock for those involved in commercial animal husbandry

- loans with traders against crops yet to be harvested (e.g., cash or in-kind pay back after harvest) or loans through village savings and loan associations (VSLA)

- consumption of other, non-cereal staples, including roots and tubers, as crops such as cassava, taro, and potato can generally be harvested during the growing season of rice, which coincides with the hunger period.

While these coping strategies provide families with immediate (temporary) solutions to manage the hunger season, many informants expressed interest in accessing more systematic (permanent) solutions. In addition to the need to increase yields through improved production practices, informants mentioned the need to improve household planning, engage in savings practices, and/or access food conservation and transformation technologies. The youth group president in the Yende district (Kissidougou) concluded a discussion held with a key informant group by saying “we are too dependent on a non-productive agriculture.” Annex 3 provides a full overview of food commonly grown and/or marketed in the SPRING assessment area, as well as its importance as part of consumption patterns.

Agricultural Productivity

For the great majority of rural smallholder producers, the average yield of agricultural commodities is low. This is particularly true for cereals (rice, maize, fonio, sorghum, millet), roots and tubers (cassava, tarot, potato), leguminous crops/pulses (peanuts, cowpea, pigeon pea), vegetables (okra, eggplant, tomato), and fruits (banana, mango, avocado, orange, papaya) grown in the assessment area. A variety of factors that contribute to these consistently low agricultural productivity levels are summarized in the table 5 below.

Table 5. Factors Affecting Agricultural Productivity in Guinea

| Insufficient knowledge/access to information about yield increasing and sustainable best agricultural practices as well as new technologies to ensure the desired effect of inputs, land preparation, and crop maintenance related to production investments. |

| Insufficient access to improved seed and plant material including short-cropping cycle varieties and hybrids, is a serious problem. Key informants confirmed that the demands for seed (especially improved seed) far surpass the supply every year. Insufficient seed is compounded by the fact that many producers are so desperate for food or cash during the hunger period that they often do not conserve adequate (or any) seed stock for the next cropping season. |

| Inconsistent access to appropriate yield increasing inputs including improved seed, appropriate fertilizers, and crop protection products. While the GOG has subsidized agricultural inputs in recent years for different rural farming communities, the timing of delivery is not always opportune; the composition of the fertilizer is not necessarily appropriate for crops grown (e.g., blanket fertilizer formulas, generally NPK 15-15-15); and the general purchasing power of many farmers does not allow access to sufficient inputs. These access-related issues have a direct [negative] effect on the efficiency of the farming system, including labor requirements. |

| Inadequate access to productive arable land as the total area of fertile improved (semi-irrigated/inundated) lowland is limited throughout the assessment area. Where possible, smallholders will cultivate in lowland areas; however, many who do not have access to these parcels are required to farm on drier uplands where water is less abundant and the potential for soil degradation and erosion is much higher, thus affecting potential yield levels, particularly when best agricultural practices are not being applied. |

| Poor agricultural practices/land management have additional negative effects on the overall productivity of available land, often resulting in: 1) shortened fallow periods; 2) increased (and sometime abusive) forest and tree cover clearing; and 3) forest and shrubbery fires that prompt conflicts between agricultural producers and livestock breeders over arable versus grazing land. |

| Inequality of access to productive land related to gender impedes access to the generally more productive lowland area where there is an abundance of water throughout the rainy season. Men generally hold access rights to lowland during the rainy season production period. Women tend to only gain access to lowland areas after the rainy season, once the rice is harvested, limiting their production to pulses (cowpeas, pigeon peas) and sometimes peanuts, as well as vegetable gardening on lowlands during the dry season. |

| Inequality of control over crop production influences women’s workload and access to income. While men generally grow staple crops, women tend to be more involved in vegetable and fruit production. During the rainy season, women provide labor for land preparation and crop maintenance on lowland and upland fields on which the men grow their (staple) crops. Home gardens provide opportunities to women for smaller scale and more intensive production of cassava, taro, potato leaves, okra, ginger, and different fruit trees that can be found around the house. Control of these crops can offer women opportunities for commerce, as well as processing of surpluses, although these activities essentially add to their workload. |

| Extensive nature of the traditional production system directly affects the efficiencies of a sustainable and productive farming system, be it for cereals, pulses, vegetables, fruits, or other crops. This is generally a result of lack of knowledge about and application of best agricultural practices, combined with limited access to agricultural machinery and yield-enhancing inputs. While intensification of agriculture tends to require initially more labor from both men and women, it generally also has a higher rate of return on labor, as well as other [input- related] investments. |

| Limited access to post-harvest handling and processing knowledge and technologies has a direct influence on the ability to store and conserve the already limited volume of crops produced. While this is particularly true for perishable and seasonal vegetables and fruits, post-harvest losses are relatively high for cereals, pulses, roots, and tubers as well. Much of the drying, processing, and transformation of commodities is done manually by women, adding to their work load. There has been very little training in improved conservation and storage techniques, and few farmers have access to processing and transformation technologies. Few agricultural agents are aware of the potential presence of aflatoxins (particularly in peanuts and maize) and the associated health risks, including an impact on stunting. Although some agricultural experts within the MOA and ISAV, the agricultural university in Faranah, expressed interest in introducing aflatoxin control measures, no plans are currently in place to further examine this subject. |

| Shortage of agricultural labor has greatly increased over recent years, especially as rural youth are leaving for traditional mining operations particularly in Sigiuri, Mandiana, and Kouroussa. New mining discoveries in the past five years have exponentially increased the rural exodus. Farm labor traditionally provided by all members of the household (as the land preparation season coincides with school vacations) or as part of traditional community labor sharing systems is no longer available as a result of the rural exodus. The labor force responsible for cultivating the fields has thus shifted and now primarily consists of older men and women of reproductive age, thus adding to their work load. |

| New standards requiring payment for labor create an additional burden for young families who generally do not have the financial resources to attract paid labor to assist in land preparation and crop maintenance activities. A fee of 10,000-20,000 GF per laborer per day includes cigarettes, meals, and transportation. |

| The Ebola crisis contributed to expectations of payment for labor in that many community members were paid for work under Ebola assistance programs in rural communities. Although Ebola did not directly affect the majority of households in the SPRING assessment area (e.g., few direct victims at community household level), the negative result of this new expectation was cited by many key informants and NGO representatives. |

Animal Source Foods

Similar to agricultural productivity, a variety of factors also contribute to the difficulties associated with the raising of animals and the low consumption of animal source foods, summarized in table 6 below.

Table 6. Factors Affecting Availability of Animal Source Foods

| Lack of knowledge of animal husbandry and constraints to large livestock breeding also negatively affect economic opportunities derived from livestock for the great majority of rural households. Animal husbandry and livestock breeding in numbers that surpass more than 5-10 heads per family are practiced by few rural household. When practiced, cattle herding is generally conducted in an extensive manner whereby a herder is assigned to move with the cattle between different pastures. |

| Conflicts between agricultural producers and livestock owners also negatively affect the rearing of cattle and small animals (goats and sheep), which are generally held in small numbers and only corralled during the height of the production season. There was little evidence of specific animal feed production in the assessment area. The relatively high risks associated with intensive animal husbandry and related investments, including fairly common deadly animal diseases and the high cost and limited availability of veterinary services and animal medications, were cited as impediments to livestock production. |

| Commercial poultry farms are relatively rare and limited to more urban centers, which generally serve the market demand for “imported” eggs. The demand for eggs, however, was reported to be higher than the current market supply. Eggs from chickens kept at household level are generally not consumed but kept for the production of chicks for eventual consumption or sale of chicken (for meat). Commercial poultry farming (for egg production) in Kissidougou was mentioned by several informants. |

| Access to fish varies depending on location of communities. Over the course of the fieldwork, it was found that traditional and very time-intensive practices are generally used for fish farming in areas that are submerged throughout the year. While commercial fish farming is practiced in Forest Guinea (Nzérékore), these activities only started recently on a pilot scale in the assessment area with the support of Plan International. Initial results are promising and much appreciated by local communities; however, the majority of inputs/materials were sourced through the pilot project. Fingerlings are produced and available year round in Nzérékore, and options for the production of fish feed with locally sourced materials are currently under review. |

| Access to bush meat varies depending on location of communities. Although officially discouraged during the height of the Ebola crisis, bush meat hunting is still exercised, and various forms of bush meat were cited by community members as common sources of food. Agouti (a wild bush rat) was overwhelmingly mentioned as the primary source of bush meat and seen for sale at local markets visited in the assessment area.5 |

Dietary Diversity and Market Choices

The health and agricultural service agents, as well as general rural population in the assessment area, appear to have little knowledge of the nutritional values of various foods. There are great differences in terms of availability of certain foods due to the seasonality of these products (fruits and vegetables mostly), as well as limited conservation and processing opportunities. People’s knowledge of which foods make up a “nutritious plate,” food utilization, and preparation best practices is very limited.

While a great number of fruits, roots/tubers, pulses, and vegetables could be available in fresh or dried/processed form throughout the year (if proper storage, conservation, and processing options were available), the regular intake of animal source protein (eggs, chicken, fish, meat) is extremely low to non-existent for the majority of households, and often limited to once a week or less, or holidays and celebrations. Complementary plant protein sources (peanut, cow/pigeon pea, soybeans) are grown by some local producers, but generally do not represent an important portion of the regular food consumption at household level in the assessment area. Annex 3 provides a full overview of “Food Access and Dietary Consumption Patterns” as found in the assessment area.

Gender issues and traditional family practices continue to [negatively] impact the availability and thus consumption of protein-rich foods by young children and women of reproductive age, as adult and young men get preferential treatment when it comes to eating meat and other protein sources.

A number of health agents, as well as local women, mentioned the usefulness of cooking demonstration classes as a way to increase consumers’ knowledge of nutritional values and food utilization and promote behavior change of preparation practices. Although some projects in the past have made efforts to start these classes, informants commented that these activities were not set up in a sustainable manner. Food demonstration classes often ended as soon as efforts were no longer supported with resources from a project.

Distances to markets and health centers vary greatly by sub-prefectures (from 3 to 25 kilometers or more), and a shorter distance does not always indicate better access, as the majority of rural villages do not have regular (paved) road access. This poor infrastructure results in serious challenges, especially during the rainy season, when some villages can be completely isolated. The majority of rural households, however, do attend the nearest weekly market for buying and/or selling goods, purchasing only enough perishable foods, especially fresh fruits and vegetables and animal source foods, to meet family needs for a few days because storage, conservation, and processing of perishable foods is rarely done . While traders and marketers will frequent larger (peri-)urban markets, the bigger prefectural markets (where health centers are generally located) are visited less frequently by rural household members unless they have particular need. (See annex 4 for maps of Kissidougou and Faranah.)

The common responses in all areas visited by SPRING regarding what is typically purchased at the market included oil, sugar, salt, clothes, soap, and kerosene. Informants interviewed stated that expenditures depended on the need at the time. General spending priorities were consistent across regions; households spent the majority of their income on school fees, the basic food and non-food necessities listed above and, when possible/needed, home construction or improvements. When managing periods of increased earnings or “extra income,” community members indicated that they invested the additional income in acquiring small livestock, purchasing or renting additional land, and hiring additional labor for their farms. Nevertheless, it was repeated that these instances were rare, and that any additional income tended to be spent on “basic needs” such as oil, sugar, and salt.

It was clear from all meetings conducted during the assessment that the majority of the population interviewed did not prioritize the purchase of vegetables or animal source foods. As the executive secretary for Matyazo sector Ngororero district stated, "We still need partners who can change minds for people to use their purchasing power. We need to educate people; they are not managing their income well." SPRING’s impression from its interviews is that the failure to purchase animal source foods is due to both price and the fact that it is not part of the typical routine. Even when households have additional income and could afford the more nutritious foods, they are not secure enough with the consistency of the income flow to purchase higher priced commodities.

Food Plate and Feeding Patterns

To cope with periods of food insecurity, families typically decrease, both in quality and quantity, their usually already minimal diets and rely on their few existing resources. All informants confirmed that only a few families will eat more than two meals a day during the hunger season, and that food intake may only consist of one full meal per day during this period, with smaller “snacks” during the rest of the day. Of the food plate within the prefectures of Kissidougou and Faranah, families first minimize the supplements, or “condiments,” to a meal of rice with a small amount of oil. Within this sparse coping plate, even the type of oil alters with the household’s access to income. Red palm oil is the preferred oil, and a lighter market- bought (imported) vegetable oil is used when families do not have access to palm oil. Further details on consumption patterns can be found in annex 3.

While preference is given to locally grown rice, many families—especially those without access to cash to purchase imported white rice on the market—will substitute rice with roots and tubers (e.g., cassava, taro, Irish or sweet potato) during the hunger season because those are generally ready for harvest during this period. The preferred “sauce” to complement the food plate is either made up of a leaf sauce (potato or cassava leaves) or, to a lesser extent, an okra or peanut paste-based sauce.