Background and Objective | Methods | Cross-Country Findings | Observations and Discussion | Conclusions | References | Related Field Notes

Executive Summary

Overview

Between September 2012 and June 2013, the Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project conducted a landscape analysis of activities of the U.S. Government's global hunger and food security initiative, Feed the Future, in 19 focus countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, and the Caribbean. Guided by the "Key Pathways between Agriculture and Nutrition" framework, the landscape analysis mapped current interventions and pathways linking agriculture and nutrition and developed several key observations following six "Guiding Principles for Linking Agriculture and Nutrition," as synthesized by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Outputs

This exercise generated a total of 19 country profiles. Each provided a snapshot of the USAID Mission's activities and contexts in the particular country, and described the details of agriculture and nutrition interventions; the ways nutrition outcomes are to be delivered by agriculture and economic growth activities; and the strengths and challenges observed in the current activities. Promising practices that emerged from five focus countries were documented in field notes after on-site activity review and collaboration with the Missions. These outputs informed the agenda and discussions of a series of Agriculture and Nutrition Global Learning and Evidence Exchange (AgN-GLEE) workshops that focused on strengthening the pathways linking agriculture and economic growth interventions and nutritional outcomes. Representatives from USAID Missions, implementing partners, and host-country governments participated in the workshops.

In this Report: Findings, Challenges, Discussion

This report offers an in-depth analysis of the Feed the Future activities based on the country profiles, studies of promising practices, and workshop discussions. Beginning by defining the scope and methodology of the landscape analysis and introducing the two frameworks used for that analysis, the report describes cross-country findings on implementation approaches, selection of value chains, integration of direct nutrition interventions, and the agriculture–nutrition pathways active in current Feed the Future activities. Next, the report presents a number of critical issues and challenges observed in Feed the Future activities: the need for indicators of intermediate steps along the pathways; consideration of gender and social norms; targeting of both geographic regions and beneficiary groups; multisectoral coordination; and the importance of value chain selection, market access, and social and behavior change (SBC) along the value chains and pathways. Finally, the report proposes the following strategic changes to strengthen linkages between agriculture and nutrition in Feed the Future activities:

- Design and modify activity indicators and activities based on context assessments.

- Target SBC activities along all agriculture–nutrition pathways.

- Empower women by helping to build a supportive family and social environment.

- Focus on opportunities for nutrition throughout the value chains.

- Document incremental results to build the evidence base.

- Strengthen coordination and collaboration from within the Missions.

- Invest strategically in partnerships and capacity building to ensure sustainability.

Significance

Feed the Future activities have the potential to address many issues specific to integrating agriculture and nutrition. Although no quantitative assessment of the efficacy of integration under Feed the Future was provided by the landscape analysis, the snapshot that it provides helps synthesize and highlight promising practices and areas that deserve greater attention within Feed the Future activities and to a larger community of organizations that are leveraging agricultural interventions to improve nutritional outcomes.

Background and Objective

The Feed the Future Initiative

Feed the Future is the U.S. Government's global hunger and food security initiative. A whole-of-government initiative led by USAID, Feed the Future's primary goal is to reduce poverty and undernutrition by promoting growth in the agriculture sector. As of June 2013, Feed the Future was active in 19 countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC),1 where governments are "prioritizing and making investments in agricultural growth programs and where the conditions are right for investments by the U.S. Government" (USAID 2012). Since the inception of the initiative, USAID Missions in all focus countries have developed multiyear strategies that outline plans for investments in specific geographic zones, whole-of-government programming, activity implementation, and stakeholder coordination. Most Feed the Future multiyear strategies were approved between February 2011 and March 2012.

The Feed the Future Results Framework (Appendix 1) highlights Feed the Future's two main objectives: inclusive agriculture sector growth and improved nutritional status for women and children. The global Feed the Future strategy aims to reduce by 20 percent the prevalence of both poverty and stunting in children under five years of age in the areas where Feed the Future activities are concentrated, known as zones of influence (ZOI).

Landscape Analysis for AgN-GLEE

In July 2012, the USAID Bureau for Food Security contracted SPRING to plan and implement a series of Agriculture and Nutrition Global Learning and Evidence Exchange (AgN-GLEE) workshops. Leading up to these events, SPRING conducted a landscape analysis of USAID's Feed the Future efforts in the 19 focus countries. The objective of the landscape analysis was to map current interventions in agriculture and economic growth activities, as well as nutrition and health activities under Feed the Future and the linkages between the two sectors to understand how these activities will affect the nutritional status of target beneficiaries, primarily women of reproductive age and children under five years of age.

This exercise reviewed each of the 19 Feed the Future country's multiyear strategy and activity documents, then analyzed whether and how, according to available research and evidence, the current approaches and design attempt to improve nutritional outcomes. Preliminary Mission activity review findings were summarized in country profiles, which served as foundational documents shaping the agenda for the AgN-GLEEs, including Mission-specific planning discussions.

Between December 2012 and March 2013, three-day regional AgN-GLEEs were held in Uganda, Guatemala, and Thailand.2 These workshops offered presentations on the linkages among nutrition efforts, agriculture, and economic growth and included participants from 18 Feed the Future focus countries.3 All workshops followed similar agendas (Appendix 2). The primary objective was to provide participants—staff from USAID and other Feed the Future partner agencies from across the U.S. Government, host-country government partners, and implementing partners—with a practical forum for sharing their experience in agriculture and nutrition and learning from U.S. Government activity experience.

Methods

Scope of the Landscape Analysis

For each of the 19 focus countries, a comprehensive review of USAID-supported Feed the Future strategies and activities was conducted to identify the Mission's implementation status and operational approach, including the main interventions supporting agriculture; the direct nutrition and health activities; and the relevance of the pathways linking agriculture and nutrition.

As part of the review, the SPRING team developed five field notes4 to showcase emerging lessons and promising practices within selected countries. Missions and Feed the Future activities were self-identified or recommended as candidates for in-depth study based on their distinct approaches to agriculture–nutrition integration and potential for scaling up. SPRING staff conducted on-site review of select Feed the Future activities in Senegal (USAID's Yaajeende Project), Honduras (the ACCESO Project), and Bangladesh (SPRING/Bangladesh); and facilitated Missions in Guatemala and Nepal to summarize their experiences of multilevel coordination in the design and implementation of key Feed the Future activities.

- Senegal: Field data collection focused on the coordination of multisectoral stakeholders at different levels, including Mission, activity, government, private sector, and community.

- Honduras and Bangladesh: Field review work explored the design and rollout of integrated nutrition and agriculture trainings.

- Guatemala and Nepal: The landscape analysis team helped USAID Missions reflect upon their internal processes and activities, specifically on critical operational details, decisions, and actions that led to establishment of integration and coordination mechanism for the Mission's Feed the Future activities.

In all, the landscape analysis generated 19 Feed the Future country profiles and five field notes featuring innovative and promising process and operations practices. Results from the activity review were presented at four AgNGLEEs— three regional workshops (in Guatemala, Thailand, and Uganda) and one in the United States. This final report presents the global findings and offers observations and recommendations for future programming.

All information described below is up to date as of January 2013 for African countries and April 2013 for LAC and Asian countries.

Data Collection and Analysis

The landscape analysis was conducted primarily via a desk review of each country's Feed the Future multiyear strategy and key activity documents. Multiyear strategies were downloaded from the Feed the Future website. An inquiry sheet was emailed to each Mission's Feed the Future point of contact to identify activities that the Mission counts as part of the Feed the Future portfolio and that have defined nutrition objectives and/or indicators.

A data extraction table and coding system were created for the document review. Based on the extracted data, a profile was drafted for activities in each country following a template developed by the landscape analysis team. Next, key-informant interviews were conducted with the Mission staff and representatives of implementing partners to obtain supplementary information. A generic interview guide was developed to further understand the background and context of the Feed the Future activities and to obtain clarification on specific issues that emerged from the document review. The draft Feed the Future profiles were then revised and shared with each Mission for additional feedback. Country profiles are dynamic internal USAID documents, but the findings from each country's 2013 profile exercise are included in this landscape analysis.

Frameworks for Landscape Analysis

The landscape analysis and discussions of Feed the Future activities and portfolios were grounded in two frameworks: "Seven Key Pathways between Agriculture and Nutrition" (Gillespie, Harris, and Kadiyala 2012), and "Guiding Principles for Linking Agriculture and Nutrition" (FAO 2013; see also Appendices 3 and 4). These pathways and principles were identified to guide the landscape analysis because they were based on the best available global evidence of the linkages between agriculture and nutrition.

Agriculture–Nutrition Pathways

The seven pathways linking agriculture and nutrition (Box 1) developed over time and listed in Gillespie (2012), reflect ideas on the agriculture–nutrition connection advanced by earlier writers.5 The emphasis on women in pathways 5–7 is supported by the global evidence that shows income controlled by women has a greater positive effect on children's nutrition than that controlled by men (Herforth, Jones, and Pinstrup-Andersen 2012). Empowering women through targeted agricultural interventions can have a strong positive effect on child nutrition and household food security (Hawkes and Ruel 2008).

Although the agriculture–nutrition pathways served as one analytical framework for the landscape analysis, they were not developed prior to the design of Feed the Future strategies, activities, or proposals under review. The landscape analysis did not attempt to rate activities and strategies against the pathways; it used them to guide analysis of the Feed the Future activities.

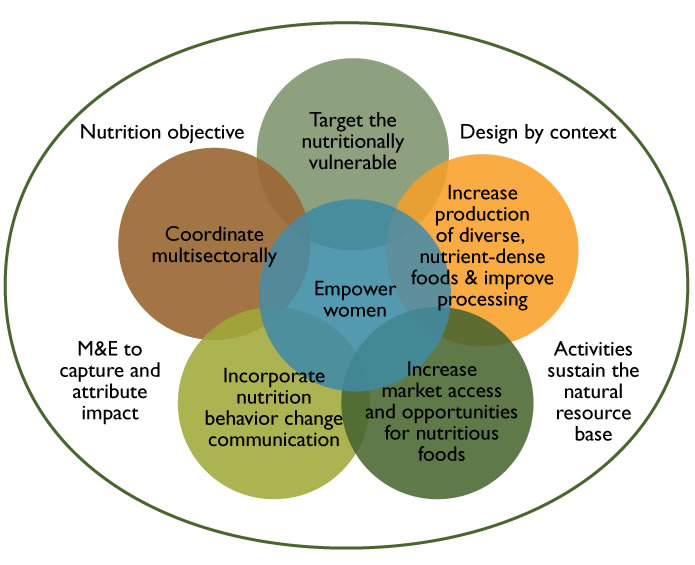

Guiding Principles

The guiding principles, synthesized by FAO (2013), are based on review of a number of organizations' guidance documents on improving nutrition through agriculture. The principles represent the emerging global consensus on how to link agriculture and nutrition, and were finalized through an extensive consultative process with multiple stakeholders, including nongovernmental organizations, academic organizations, United Nations food and nutrition agencies, and donors. Six of the twenty principles were determined to be most relevant to the scope of this landscape analysis (Ag2Nut Community of Practice 2013); these six principles covered the agriculture–nutrition program planning phase (targeting and multisectoral coordination) and action phase (production of diverse foods, increasing market access, incorporating SBC, and women's empowerment), per Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. SIX KEY GUIDING PRINCIPLES TO IMPROVE NUTRITION IMPACT THROUGH AGRICULTURE

Limitations of Landscape Analysis

The landscape analysis had several limitations. First, the exercise had a tightly defined scope to focus on linkages between agriculture (economic growth) and nutrition, and to inform AgN-GLEE workshop agenda and discussions. The landscape analysis did not attempt to assess activity design and implementation details or indicator selection or monitoring and evaluation plans. Second, the landscape analysis relied primarily on documents supplied by the Missions, which were often not up to date because of regulations on sharing procurement-sensitive information and lead time between action and reporting. In addition, field research was limited in scale as many Feed the Future activities had only just commenced implementation at the time of this review. Therefore, the country-specific activity analyses and this report may not capture the most current situation on the ground. Finally, staff turnover in some Missions affected the completeness of the information collected, especially pertaining to the initial design phase of Feed the Future activities and strategies.

Cross-Country Findings

Implementation Status of Feed the Future Activities

Feed the Future activities are relatively young, with implementation timeframes often less than two years (except in the case of activities that were retrofitted; see "Activity Approaches"). By the end of 2012, at least one Feed the Future activity had been underway for more than a year in each of the 12 African focus countries. Within the LAC region, the Guatemala Mission awarded all activities in 2012. In Haiti, all activities had started a year before the landscape analysis research, with the exception of one nutrition initiative that had not yet been awarded. The Honduras Mission's portfolio focuses on one activity that completed its second year of implementation in April 2013. In the four Asian countries, the Cambodia Mission's flagship activity and all of the Tajikistan Mission's activities were in their third year of implementation. The Nepal Mission's activities had completed more than a year, except for one major Feed the Future activity not awarded until February 2013. In Bangladesh, all but one activity had been operational for more than a year.

BOX 1. PATHWAYS FROM AGRICULTURE TO IMPROVED NUTRITION

- Agriculture as a source of food.

Production → Consumption - Agriculture as a source of income to affect food purchase.

Income → Food Production - Agriculture as a source of income to affect health care purchase.

Income → Health Care Purchase - The link between agricultural policies and food prices.

Food Prices → Food Purchase

Woman-Specific Implications of the Increased "Feminization" of Agriculture

- Women's own nutritional status due to workload changes.

Women's Workload → Maternal Energy Use - Women's ability to manage the care, feeding, and health of young children given their time constraints.

Women's Time Use → Care Capacity - Women's socioeconomic status and ability to influence household decision making and intrahousehold allocations of food and other resources.

Women's Control of Income → Resource Allocation

Source: Gillespie, Harris, and Kadiyala (2012)

Activity Approaches

The landscape analysis found that Feed the Future was promoting three different approaches for implementing agriculture and nutrition interventions; a number of Missions used more than one.

Three Main Approaches

- Integrated and/or flagship activities: Where the Missions take this approach, a leading activity spearheads a Mission's Feed the Future work. Such activities may provide both agriculture and nutrition services through an integrated delivery platform; they may also focus on providing services that are either primarily agricultural or primarily nutrition related. Examples of this approach are found in Honduras and Cambodia.

- Co-locating activities: This approach involves placing multiple activities—each usually focusing on a single intervention type (e.g., health and nutrition, agriculture, or economic growth)—in one geographic area. The level of overlap in areas and target population among activities is different. In Bangladesh and Guatemala, all activities work within the same units in the ZOI. Activities in Uganda and Zambia have only partial overlap in geographic area within the ZOI.

- Retrofitting ongoing activities: Activities following this approach modified activities that were designed and implemented before Feed the Future's inception by incorporating new or strengthened nutrition interventions, indicators, or geographic targeting to respond to the new Feed the Future mandates.

Approaches by Region and Country

- Asia: Both the Cambodia and Nepal Missions designed a flagship activity. The Bangladesh Mission co-located Feed the Future activities in its ZOI. The Tajikistan Mission retrofitted several existing activities and moved them into the ZOI.

- Africa: Nine of the twelve African Missions co-located multiple activities in the Feed the Future ZOI; eight Missions designed flagship nutrition and other health and/or agriculture and economic growth activities; and six Missions adopted both approaches.

- LAC: The Guatemala Mission co-located all Feed the Future activities in the same 30 municipalities. The Haiti Mission is planning to co-locate several activities (but not all) within a designated development corridor. The Honduras Mission designed an integrated activity, which is also the flagship activity of the Mission's Feed the Future work.

Selection of Zones of Influence and Target Populations

According to the documents reviewed, the selection of Feed the Future ZOI and target populations was most commonly based on poverty and undernutrition rates, although a number of other factors listed here were also taken into account.

Regional Variations in Selection of Zones of Influence

There are regional variations. For example, the availability of natural resources, such as arable land and water, were considered in Asia when establishing the ZOI. In Africa, Feed the Future strategies tended to emphasize agriculture and income growth potential and alignment with the priorities of national governments, the U.S. Government, or other international donors. All LAC countries focused on levels of food insecurity and hunger. One LAC and three African Missions considered the proximity of the proposed ZOI to major trade roads and markets, and two Asian and two LAC Missions considered demographic issues (e.g., population density, male migration) in ZOI selection.

Target Populations

The documents reviewed clearly stated that the primary targets of Feed the Future agriculture and economic growth interventions are smallholder farmers, including women farmers, whereas direct nutrition and health activities under Feed the Future mostly target women and young children.

Gender: Nearly half the activities specifically target women of reproductive age, pregnant and lactating women, and children under two (e.g., in Bangladesh, Nepal, Tajikistan, and Zambia) or under five years (e.g., in Haiti, Ethiopia, and Ghana) with nutrition and health interventions. Uganda's Feed the Future portfolio stands out with a broad range of nutrition and health activities that focus almost exclusively on children up to 18 years of age and women. Little information was found on men's participation and responsibilities relating to nutrition, except in a few activities that focus on all household members (e.g., HARVEST in Cambodia, ACCESO in Honduras).

The vulnerable: Activity documents and multiyear strategies often refer to "vulnerable farmers" as target beneficiaries. Most activities' actual beneficiaries appear to be smallholder farmers who possess or have access to some productive assets—such as farmers who own less than one hectare of land and live at or near the country-defined poverty level—and often exclude the most destitute population in the ZOI. A few activities (e.g., in Honduras and Nepal), developed strategies to work with the "most vulnerable" populations, such as landless agricultural laborers. These activities include specific interventions designed to prepare people to participate more readily and successfully in agriculture and economic growth interventions. In a few other locations, Feed the Future is coordinating with activities that target the poorest of the poor and most food insecure, such as Food for Peace programming.6

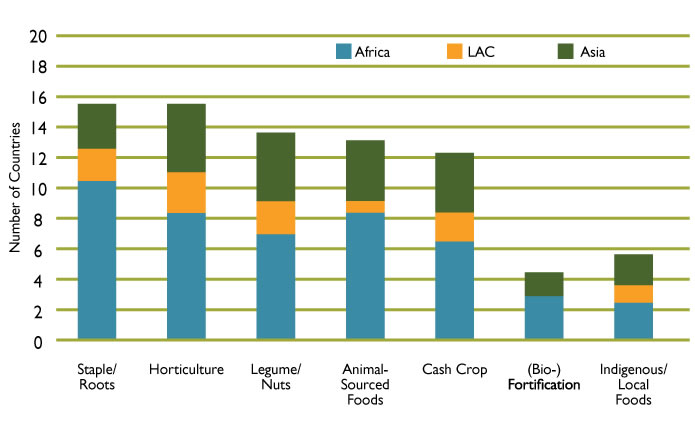

Value Chains and the Selection Criteria

Feed the Future emphasizes a value chain approach to advancing broad-based growth through development of the agriculture sector. A value chain is "a supply chain in which value is added to the product as it moves through the chain…described by the series of activities and actors along the supply chain and by what and where value is added along the way for and by these activities and actors," per Hawkes and Ruel 2011. In the documents reviewed, Feed the Future activities identified many potential crops for value chain development (Appendix 5). In this report, they are grouped into seven categories that are not mutually exclusive (Figure 2), based on:

- Relevance to health and nutrition: Four categories— grains, roots, and tubers; legumes and nuts; animal- sourced foods (i.e., dairy, eggs, and flesh meats from mostly small animals and aquaculture); and foods from horticulture (i.e., fruits and vegetables)—were created to capture the food groups used to measure minimum acceptable diet (MAD) for children ages 6 to 23 months and women's dietary diversity, as listed in the Feed the Future Indicator Handbook (USAID 2013).

- Relevance to agriculture and economic growth: Three categories (cash crops; conventionally fortified and biofortified crops; and indigenous foods) were created to capture the interest of Feed the Future investments in agriculture and economic growth, specifically income generation, agricultural technology, and sustainability.

FIGURE 2. FEED THE FUTURE VALUE CHAINS BY GROUP

Value Chains

Sixteen of the nineteen Feed the Future Missions opted for staple/root crops and horticultural value chains. Maize, selected in 11 Feed the Future portfolios, was the most commonly chosen crop. In-depth review revealed that although nine African Missions selected horticultural value chains, the available documents do not often clearly state the types of crops, level of funding priority, or ultimate use of produce (e.g., for domestic sales and export versus for consumption). No definitive findings on this critical issue could be located, likely because Feed the Future activities were still in the early stages.

On the other hand, documents from Honduras and all four Asian Missions clearly listed the wide variety of fruits and vegetables that were selected for both sale and consumption, and annual reports for selected activities have shown some initial results. For instance, Cambodia's HARVEST activity increased the commercial horticulture income of 6,000 targeted households by an average 250 percent. The horticulture activity in Bangladesh increased daily per capita vegetable consumption in the ZOI to 110 grams, twice the national average.

Meanwhile, regional differences were found in value chains involving legumes and nuts, and animal-sourced foods; both of these value chains were selected by all Asian Missions and in many African Missions. Four African Missions also chose to invest in growing biofortified crops or fortifying select processed staple crops. LAC and Asian Missions focused heavily on conventionally fortified crops, aside from small-scale development of the orange-flesh sweet potato.

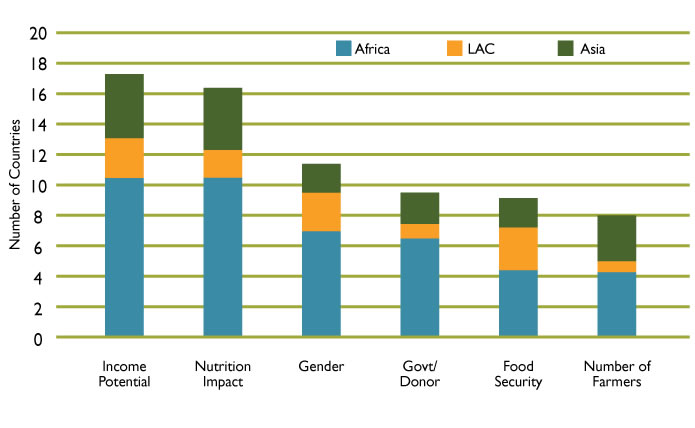

Factors Behind Value Chain Selection

Documents reviewed for the landscape analysis, especially those outlining the multiyear strategies, cited numerous factors considered in determining which value chains would be developed under Feed the Future activities. These factors can be grouped into six distinct categories (Figure 3). Globally, nutrition impact and income growth potential were cited by almost all countries, supporting the twin goals of reducing poverty and eliminating hunger. And because gender is a cross-cutting theme of Feed the Future, many countries were explicit about the intention to involve women in value chain activities or to invest in crops traditionally tended by women.

FIGURE 3. FACTORS CONSIDERED IN FEED THE FUTURE VALUE CHAIN SELECTION

Regional Emphasis

Regions have varying considerations when selecting value chains:

- Africa: Missions commonly cited the interests and opinions of the U.S. Government, the host country government, external experts, and donor organizations as influential.

- Asia: Missions were consistent in combining considerations of poverty, undernutrition, and number of farmers already involved in production of specific types of food items when selecting target value chains.

- LAC: All three focus country Missions selected value chains based on their potential contribution to food security.

Multiyear strategies and activity documents described other factors that influenced value chain selection, among them, availability of land and water; demographic trends and characteristics; climate issues; and biodiversity threats. A few activity documents also described considering unmet domestic demand for certain crops, including vegetables, and the potential for technical improvement relating to a certain crop or farming type (e.g., seeds and farming technologies for rice and aquaculture).

Integration of Nutrition Activities in Feed the Future

Most multiyear strategy papers and activity documents incorporated or plan to incorporate nutrition and/or health education and communication messages into proposed agriculture and economic growth activities of Feed the Future. These messages are often adapted from the essential nutrition actions or the community feeding package for infants and young children; in a few cases, the education packet also includes materials outlining essential hygiene actions or messages about water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH). A few documents described plans to include agricultural extension workers in delivering basic nutrition messaging (e.g., in Ethiopia, Haiti, and Nepal). Other activities are already putting such cross-training and joint training interventions into place (e.g., in Bangladesh, Liberia, Tajikistan, and Senegal).

According to the documents reviewed, several Missions attempted to adapt these essential messages to local contexts to enhance uptake of messages and promote changes in behaviors that have nutritional benefits. The adaptation of these messages was most often facilitated by context analyses carried out by Missions or individual activities as they examined current programming in health, nutrition, or agriculture. Such analyses, done in varying levels of scope and depth, sought to understand government and private sector capacities, gender concerns, and undernutrition and demographic trends. Recommendations from these assessments—particularly in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Honduras, Kenya, Rwanda, Senegal, Tajikistan, and Uganda—often become the basis for interventions that:

- Aim to change people's decisions and behaviors relating to crop production and marketing and to food purchase and consumption.

- Address the various barriers to adopting behaviors that are known to improve nutritional outcomes.

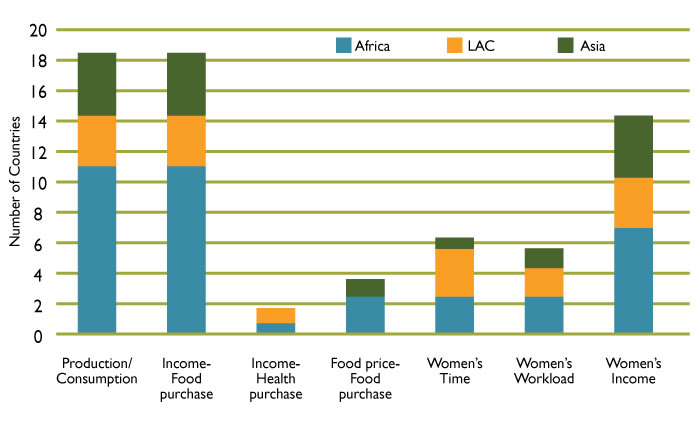

Agriculture-Nutrition Pathways

Feed the Future multiyear strategies and activities were developed before the publication of the agriculture–nutrition pathways (Box 1). Ex-post analysis found that one or more of these pathways was adopted in Feed the Future multiyear strategies, either explicitly or implicitly (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. EXPLICIT AND IMPLICIT AGRICULTURE–NUTRITION PATHWAYS ADOPTED

Own Production → Food Consumption and Income → Food Purchase

The landscape analysis review found that all USAID Missions assumed that two pathways would turn gains from the agricultural interventions into nutrition outcomes: Own Production → Food Consumption and Income → Food Purchase.

Overall, in the Feed the Future documents reviewed, the Own Production → Food Consumption pathway appears to emphasize mostly the consumption of horticultural crops produced in smaller-scale home and community gardens. Activities promoting value chains for staple crop production assumed the commodity would contribute to households through both home consumption and sale to generate income.

BOX 2. ILLUSTRATIVE INTERMEDIATE RESULTS TO BE MONITORED ALONG AGRICULTURE–NUTRITION PATHWAYS

Production → Consumption Crop yield, number of animals raised and butchered for home consumption, varieties grown in gardens, quality (varieties) and quantity of foods stored at home, varieties and quantity of foods prepared and served.

Income → Food Purchase A viable market accessible to target population where local producers sell nutritious foods.

Income → Health Care Purchase Availability of and access to quality facility- and community-based health services, types of services provided and used by target population, stock management, care-seeking behaviors (time waited before taking children to care, demand for preventive services).

Food Prices → Food Purchase Supply and demand statistics, food price information.

Women's Workload → Maternal Energy Use Women's body mass index, micronutrient status, weight gain, resting time during pregnancy, birthweight.

Women's Time Use → Care Capacity Time spent on farm and non-farm labor and child care (hygiene, interaction, playtime), feeding practices (breastfeeding, complementary feeding frequency, kinds and quantities of food fed to children, feeding styles), contribution of other caregivers to child care demands.

Women's Control of Income → Resource Allocation Income controlled by women, food intake of women and children versus men (sequence, variety, quantity).

Income → Health Purchase Pathway

Very few activities focus on the Income → Health Purchase pathway. Activities in Uganda and Honduras are exceptions. One document from the Honduras ACCESO project states: "Improved household income should increase choices with respect to food purchases, access to health care…" Uganda's multiyear strategy describes the rationale that farmers will sell maize (depending on price) or coffee to purchase other foods and/or health products.7

Food Price → Food Purchase Pathway

This pathway was described in documents from only a few Missions (Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Liberia). Bangladesh's multiyear strategy hypothesizes that increasing demand for diversified crops will raise farmer incomes and reduce food prices. Because previous assessments found that production increases in productive areas would ultimately increase overall food availability, Ethiopia's multiyear strategy assumes that spillover effects from more productive regions (i.e., ZOI) will benefit people living in more vulnerable regions. Liberia's documents predict that Feed the Future activities will improve food transport, processing, and marketing; generate lower food prices; and increase the entire population's ability to purchase foods.

Pathways Concerning Women

Most LAC activities explicitly emphasized the Women's Workload → Maternal Energy Use and the Women's Time Use → Care Capacity pathways in their multiyear strategy and procurement documents. In particular, when mentioning the need for labor-saving technologies (e.g., drip irrigation, eco-stoves, multiple-use water systems), it was implied that women would benefit from these technologies. However, activity design documents did not always reflect these same ideas, revealing some disconnect between theory and implementation.8 All Asian and LAC Missions have reasonably clear statements and have planned and implemented explicit actions to strengthen the Women's Control of Income → Resource Allocation pathway. In African multiyear strategies, the discussions about this pathway were more implicit, with less-detailed descriptions of the actions needed to empower women and to adjust women's roles and responsibilities within agriculture and nutrition activities.

Observations and Discussion

The landscape analysis identified several challenges and practices common to Feed the Future activities, which could affect the nutritional outcomes of agricultural investments. Following is a discussion of these key issues and recommendations.

Inclusion of Nutrition Objectives and Indicators

The landscape analysis found that all multiyear strategies clearly recognized nutrition as a key component of Feed the Future, with all objectives sections and results frameworks including explicit statements on nutrition. However, the statements are often qualitative.

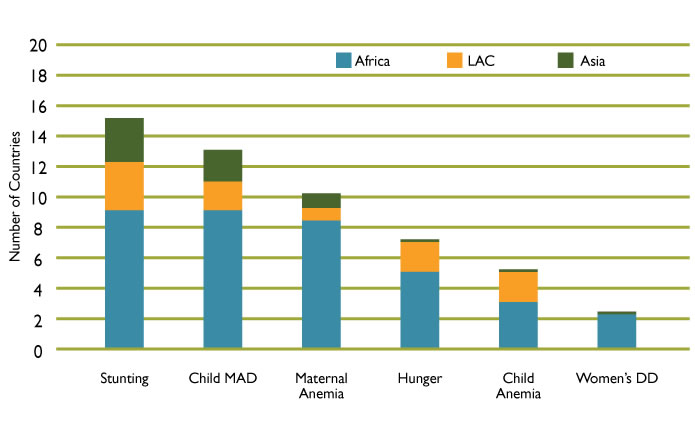

Most countries' multiyear strategies, with the exception of Bangladesh, Rwanda, and Tajikistan, include several standard nutrition indicators chosen from the Feed the Future Indicator Handbook (Appendix 6). Many activities use both standard and custom nutrition indicators; the most commonly used standard indicator is the prevalence of stunting (n = 16; Figure 5). Some agriculture and economic growth activities that claim to work toward nutrition outcomes have no nutrition-specific activities or indicators.

FIGURE 5. COMMONLY SELECTED NUTRITION INDICATORS IN FEED THE FUTURE ACTIVITIES

Two Feed the Future portfolios rely on activities initiated under Food for Peace9 to deliver nutrition interventions. In these cases, the non-Food for Peace activities tend not to have nutrition indicators. In general, activity documents did not describe the rationale for indicator selection. Perhaps the apparent absence of justification is because many activities were still in the early stages of indicator development at the time of this review. As long as indicator development is ongoing, it might be relevant for each Feed the Future activity to reevaluate why certain standard indicators were selected or custom indicators created and whether these indicators are appropriate.

MONITORING INTERMEDIATE STEPS ALONG PATHWAYS

Review of Feed the Future monitoring and evaluation plans was beyond the scope of the landscape analysis. Nonetheless, a few documents reviewed discussed the monitoring of intermediate steps along the agriculture–nutrition pathways (Box 2). A number of Missions proposed measuring not only the production outputs of the selected value chain crops but also the quantities sold and consumed. Notable examples include the Horticulture Project in Bangladesh, the Integrated Improved Livelihoods Project (IILP) in Rwanda, and the Maternal and Child Health Project in Tajikistan.

Monitoring intermediate steps is critical because such documentation has the capacity to generate much-needed evidence on how agriculture actually contributes to nutrition and to help track progress on whether and how Feed the Future investments in agriculture are having nutritional outcomes. Because of the existence of non-Feed the Future activities and of small catchment areas that cannot be expected to influence national-level measurements, nutrition improvements in Feed the Future ZOI are unlikely to be attributed solely to interventions under this initiative.10 Building a broad evidence base along the agriculture–nutrition pathways will help establish the plausibility argument that observed nutrition impacts are indeed due to Feed the Future investments. In-depth research is needed to develop indicators that will measure progress along the pathways and ascertain the technical, human, and financial resources and capacities needed to plan, conduct, report, and respond to these monitoring activities and results to maximize Feed the Future's impact.11

Tackling Women's Roles and Gender Norms

Gender is a cross-cutting theme of Feed the Future and is mentioned in documents from all Missions, in terms of both control of resource allocation among household expenses and of women's time use, labor burden, and access to income and resources. Observations on gender statements in the documents reviewed are as follows:

Women's Time and Workload Constraints

Women's time and workload constraints are widely recognized determinants of undernutrition. Nearly every Feed the Future activity targets women's participation in nutrition education sessions and other interventions, regardless of the demands on their time laboring in home food production and on other household and value chain activities. A number of Feed the Future activities have proposed and/or implemented activities to mitigate these constraints. In Honduras, eco-stoves were introduced to eliminate time and labor of fetching fuel. In Uganda, Feed the Future activities introduced composite flour mixes made with locally available ingredients which can be quickly cooked as complementary foods. Nepal's multiyear strategy paper stresses the importance of specific "female-friendly" farming practices and explicitly considers child care, transportation, and labor-saving technologies (e.g., corn huskers and small tractors) to promote women's inclusion in activities.

Gender Roles and Norms

In order to improve nutrition by increasing women's participation in agricultural activities and control of income and resources, a sound understanding of current gender roles and norms is critical. Several Missions have demonstrated efforts in this area. For instance, activities in Honduras and Bangladesh have created on- and off-farm income-generation opportunities (e.g., sales of handicrafts and home garden produce), to allow women to work close to home, thus accommodating their childcare duties. This approach also acknowledges the importance of cultural and social norms that may limit women's ability to work outside the homestead. In Bangladesh, the Horticulture Project capitalizes on established gender roles by working closely with women to improve their skills in areas where they already have significant responsibilities, such as seed production, crop management, cropping systems, and grafting. Nepal's Suaahaara activity applied a gender equality and social inclusion framework that led to modifications of the homestead food production model within one year. In Tajikistan, Feed the Future activity staff have worked to include husbands and in-laws in SBC activities to empower women by changing intrahousehold decision-making and power dynamics.

In addition, several African Feed the Future activities selected value chains based in part on their potential impact on women, notably, crops in whose cultivation women were already involved, including ground nuts and soy in Malawi and horticulture and maize in Tanzania. The Tanzania Mission's procurement documents specifically require implementers to consider how interventions will improve women's control of resources without negatively impacting infant and young child feeding and care.

Targeting Geographic Areas and Beneficiaries

Feed the Future countries considered a number of factors when selecting ZOI. Commonly cited were prevalence of poverty, food insecurity, and child undernutrition; agricultural output and potential for growth; U.S. and national government and donor priorities; and water and land resources and infrastructure.

Reaching New Areas

Ethiopia and Ghana exemplify how Feed the Future is being used as a catalyst to reach regions, communities, and farmers that have not been focused on by past USAID programming. The Ethiopia Mission has traditionally invested in the most vulnerable regions and people, but devotes a large proportion of Feed the Future resources to the relatively better-off productive zone. Potential for significant gains in agricultural production is highest in this area, and the nutritional status of women and children is poor. The Ghana Mission sited its Feed the Future flagship activity in the poorer northern region, previously underserved by USAID activities.

Achieving Better Coverage in Co-Located Activities

The landscape analysis found that many co-located activities have not yet established information-sharing mechanisms or coordinated work plans to ensure coverage of beneficiaries in the same targeted geographic area. Lack of such coordination undermines the co-location approach and may reduce the impact of activities.

Using one promising model, the Bangladesh SPRING project leads both homestead food production and nutrition training for field agents in the government service delivery systems and agents of other USAID-funded activities operating in the ZOI. SPRING also shares information on land and water access of beneficiary households with other activities that work on aquaculture and horticulture. The Guatemala Mission is creating department-level bodies to facilitate coordination between partner activities and is also supporting cross-sector coordination and communication within and across relevant Mission offices.

Working with More Vulnerable Beneficiaries in Zones of Influence

Although primary Feed the Future agriculture and economic growth activities focus on value chain development and strengthening, Feed the Future activities rarely target the most vulnerable populations—people who are landless, ultra-poor, and without the basic resources to invest in commercial activities. Documents from Guatemala and Malawi explicitly place ultra-poor farmers lacking the resources needed for participation in value chain activities outside the scope of Feed the Future agriculture interventions. Instead, this group would be targeted by health and nutrition activities and Food for Peace-funded activities (if they exist). Different Feed the Future activities take different approaches to this challenge:

- Some work closely with activities funded by Food for Peace to ensure U.S. Government investment coverage of the entire population in the ZOI.

- Some use Food for Peace to implement the nutrition component of the Feed the Future activity. For example, in Mozambique, according to the Mission, a number of nutrition and health concept notes were under development or out for procurement. (However, nutrition funding under Feed the Future is significantly less than that of Food for Peace, which will be terminated in Mozambique after the current round.)

- The Honduras and Nepal Missions had designed specific activities, such as basic literacy and numeracy training (Nepal) and basic health and nutrition education and home improvements (Honduras), to help the most-vulnerable households in the ZOI participate in Feed the Future activities.

Inclusion of Both Men and Women in Agriculture and Nutrition Interventions

Male farmers traditionally receive greater benefit from agriculture and economic growth services and opportunities than female farmers. Although Feed the Future activities aim to reach smallholder farmers of both sexes, documents reviewed demonstrate that a gender bias persists in current activities, as demonstrated by the fact that direct nutrition interventions target women and children almost exclusively.

Separating gender roles in agriculture and nutrition may narrow the benefits that a family could draw from the full range of Feed the Future interventions. If activities are not responsive to intrahousehold dynamics on agriculture and food activities (e.g. information sharing and decision making), planned outcomes from Feed the Future may be diminished. A whole-household approach (e.g., as envisioned and implemented in Cambodia, Honduras, Tajikistan, and Bangladesh) helps integrate activities aimed at increasing production and income with those aimed at improving knowledge and practices relating to food purchase and consumption. Such household-level integration ultimately benefits the entire family—women and children as well as men.

Value Chain Selection

The landscape analysis yielded two key observations on value chain selection.

Investing in Nutrient-Dense Value Chains

The documents reviewed cited nutrition content as among the most common considerations in value chain selection. Yet starchy staple crops that have lower nutrient density are promoted in 18 of 19 strategies, and of those, maize is the most popular (selected by 8 of 12 Feed the Future portfolios in Africa and 11 overall). It is understandable that staple crops are needed to help meet dietary energy requirements. However, the emphasis on staple crops in these areas inspires the question as to whether other value chains should also be invested in and promoted to ensure dietary diversity and to better supply bioavailable micronutrients and high-quality protein. Such investment toward crop diversity may better assist Feed the Future to meet nutritional goals with the limited resources available. Lessons might be learned from Feed the Future activities in Asia, which focused on more diverse and nutrient-dense crops than their LAC or African counterparts. Of all 19 Feed the Future countries, only the portfolio in Bangladesh invests in all seven value chain categories: staple and root crops, horticulture crops, legumes and nuts, animal-sourced foods, cash crops, biofortified crops, and indigenous and local foods.12

Potential Unintended Consequences on Market Prices

Aside from nutritional concerns, focusing value chain development on a limited number of crops may affect their supply, demand, and pricing. These potentially unintended consequences do not seem to be of great concern or explored at the local market level, as only a few Missions' activities proposed or carried out market analyses. An exception is the ACCESO project in Honduras, which regularly assesses market demand and constraints to determine the number of farmers targeted to grow a particular crop. Another example is Rwanda, where activities also reported having analyzed supply and demand for beans and maize before they were selected for value chain development.

Market Access to Diverse, Nutrient-Dense Foods

Feed the Future activity documents in all countries commit to promoting improved market linkages that will help targeted farmers sell their produce. Typically, this promotion involves linking producers of value chain crops— staple grains, horticulture crops, cash crops, or animal products—geared for sale to local or regional markets to generate income. These producer-market links are often achieved by creating farmer co-ops, providing market and price information, and improving transportation and other infrastructure.

Activity documents do not explicitly state plans to link those producing more diverse and nutrient-dense value chain items (often grown at smaller scale) to markets accessible to targeted activity beneficiaries. This raises the question of the availability of diverse, nutritious, locally grown foods in local markets. A primary assumption of Feed the Future is that agricultural income will enable target households to improve nutrition through purchase of nutritionally dense and diverse foods via the income– food purchase pathway. If the link between nutritious food production and local market sales is not made, this key premise may never be realized, hence undermining nutritional goals.

Supporting local markets to keep value chains for diverse, nutrient-dense products closer to both producers and consumers creates livelihoods for smallholder farmers, energizes the economic system in activity areas, and supports sustainable agricultural practices. Healthier dietary options are also made more accessible and consumption of nutritious foods may increase the likelihood that maternal and child nutrition will improve.

Social and Behavioral Change Communication along Agriculture-Nutrition Pathways

Target Behavioral Changes

Nutrition education activities are included in all Feed the Future activity designs. These activities often focus on teaching basic nutrition and target knowledge appropriate for maternal and child health and nutrition. However, in the documents reviewed, nutrition education is generally not distinguished from SBC programming, which focuses on changing behaviors that affect nutritional outcomes, such as dietary practices. Based on all activity documents reviewed, the best efforts to change behaviors attempt to guide nutrition-related behaviors of all household members (e.g., Bangladesh, Cambodia, Honduras, and Tajikistan), and/or tie the educational messages directly to selected Feed the Future agriculture value chains (e.g., Malawi and Kenya).

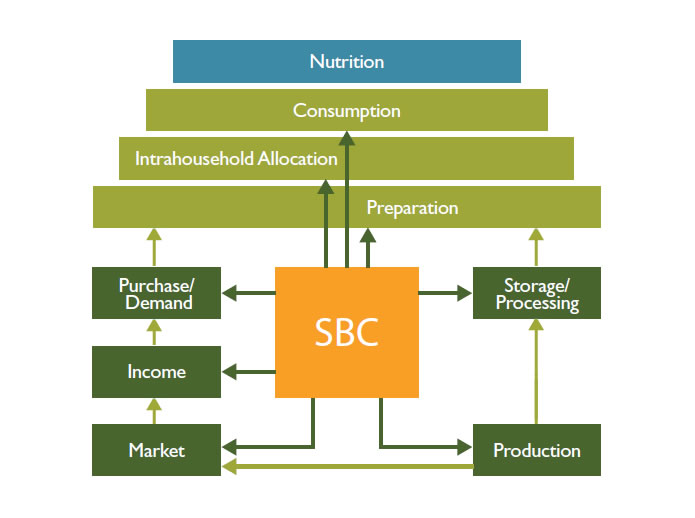

Social and Behavioral Change along the Pathways

Social and behavior change programming can be useful through the whole spectrum of activities along the agriculture– nutrition pathways, from production to consumption (Figure 6). Traditionally, SBC interventions focus on the individual and household levels to promote equitable intrahousehold food distribution among family members, healthy maternal nutrition, appropriate feeding practices for infants and young children, and food preparation techniques that conserve nutrients.

Within the two most commonly adopted pathways (Own Production → Food Consumption and Income → Food Purchase), SBC programming has the potential to achieve better household nutrition. It can do this by improving households' ability to identify and decide what to produce for home consumption and how to store and process foods to minimize spoilage and safety threats. It can also influence food purchasing, which is particularly important where agricultural activities are increasing household incomes. In turn, this consumer demand for nutritious foods can shape what the market supplies by signaling smallholder farmers to produce such foods and become more competitive in the marketplace.13

FIGURE 6. SOCIAL AND BEHAVIORAL CHANGE LINKING AGRICULTURE AND NUTRITION

Social and Behavioral Change along the Value Chains

Social and behavior change activities may also be used to address behavioral barriers in value chain development. In Senegal, for example, USAID's Yaajeende Project targets all community members with SBC activities promoting local food production and supporting linkages to markets through local private sector players. Rwanda is addressing financial barriers by linking farmers and women's groups to microfinance organizations. Clearly, some current activity designs extend the reach of SBC to agricultural behaviors.

In summary, SBC strategies can be designed to target all steps along the agriculture-nutrition pathways, as well as the value chains, to promote changes in farming practices, crop selection, and diversification; changes in decisions about food purchase, preparation, and utilization; changes in intrahousehold food distribution; and changes in post-harvest storage and processing.

Multisectoral Coordination

Why It Matters

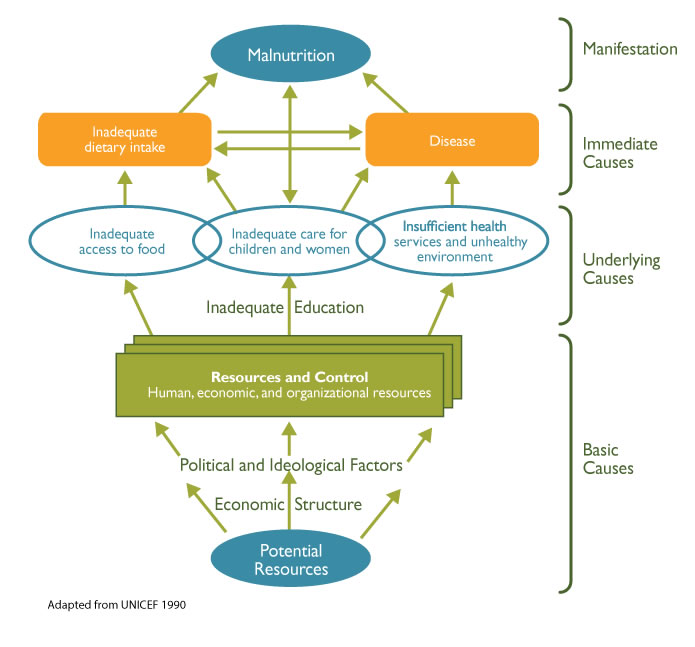

Feed the Future should avoid singling out food availability and access as the causes of malnutrition and its solutions. Consensus is growing that Feed the Future activities should further integrate agriculture, care, health, and WASH interventions, aligning with the UNICEF conceptual framework for malnutrition (UNICEF 1990; Figure 7). Increasingly, consideration is being given to such issues as food safety and environmental enteropathy (Korpe and Petri 2012).14 Clearly, most Feed the Future–required nutrition indicators cannot be addressed by direct agricultural interventions alone (Appendix 6).

Lessons from Successes

Although difficult, innovation can make coordination across sectoral boundaries feasible. The landscape analysis facilitated two Mission-led field notes in Guatemala and Nepal that chronicled resources used and steps taken to establish a mechanism to nurture the design of a truly integrated activity and coordination of co-located activities. The essential lessons from the resulting two documents are:

- Cross-fund agriculture/economic growth activities and health/nutrition activities, and use budgets as contractual procedures to ensure that activities funded by different streams and awarded to potentially different organizations are integrally implemented.

- Create an internal Mission mechanism with regular membership and meetings to design common activity objectives, discuss progress and challenges, and build relationships across offices. Use this mechanism to establish similar avenues for communication and coordination among government stakeholders and activities.

- In procurement documents, include binding language that requires coordination among activities. Specifically, promote coordinated work plans.

FIGURE 7. MULTIFACETED CAUSES OF MALNUTRITION

Conclusions

The landscape analysis of the Feed the Future activities was conducted at an opportune time because implementation of most activities was in early stages, so modifications to technical approaches and remaining procurements might still be feasible. Informed by the findings from Mission-level landscape analyses and feedback provided by participants at the AgN-GLEEs, this report proposes strategic changes in seven areas to improve linkages between agriculture and nutrition in Feed the Future activities.

Design and Modify Interventions and Indicators Based on Context Assessments

No single strategy applies to all country contexts. Value chain crops, target areas, and SBC plans should be selected and developed after careful analyses of both quantitative and qualitative data, based on the epidemiology of undernutrition and grounded in a thorough understanding of local capacities, contexts, norms, and sociocultural dynamics—particularly constraints faced by women. The rationale behind these critical design and implementation decisions should be clearly documented and regularly revisited, for example as part of an annual activity review. Continuous monitoring of the context is critical in order to adjust implementation when needed.

Empower Women by Building a Supportive Family and Social Environment

Given the constraints of their time and work load, women's involvement should be shifted to the more profitable segments of the value chain process (not just production). Informal social norms and formal laws must support women's control of on- and off-farm income and decision-making power over spending. Male family members and mothers-in-law, as well as opinion and influence arbiters in the immediate communities and society as a whole, must be targeted with messages explaining that sharing resources and joint decision making with women benefits the entire family and, indeed, all of society. These messages need to be carefully designed and context-appropriate.

Target SBC Activities along all Agriculture-Nutrition Pathways

Feed the Future activities should consider expanding beyond the narrow focus on "nutrition education" (e.g., on knowledge of nutrients and cooking demonstrations) to change agricultural practices and push translation of agricultural production gains to better health and nutrition outcomes along the seven pathways. This requires investment in context assessments, including formative research, to identify and diminish barriers associated with food production, purchase, and preparation; intrahousehold food distribution; and family members' food consumption patterns. Optimally, these barrier assessments and subsequent interventions will take a whole-household approach.

Focus on Opportunities for Nutrition Throughout the Value Chains

More awareness of nutrition and supportive activities should be incorporated into all links of the value chain. Particular attention should be paid to ensuring that value chain crops are selected to respond to nutritional deficiencies; that appropriate harvesting techniques and improved post-harvest processing preserve nutrient content; and that demand exists (or is created) for diverse and nutrient-dense foods in local markets. Maximizing opportunities in these three areas will ensure that a wide variety of food is produced, preserved, and accessible to households.

Document Incremental Results to Build the Evidence Base

Emphasis on incremental results is currently lacking within Feed the Future. The provision of these results would strengthen the evidence base for how agriculture improves nutrition. Measuring intermediate results would enhance the ability of activities to refine approaches at the appropriate time and modify action points to have greater impact. For example, indicators that measure production, sales, and consumption of value chain crops can be used to inform actions that need to be designed and strengthened to ensure targeted households' access to these foods. Feed the Future monitoring and evaluation may need to examine ways to fund the collection and analysis of such indicators.

Strengthen Coordination and Collaboration within the Missions

Mission staff identified USAID procurement procedures, staff capacity, and organizational systems, as well as unequal funding for agriculture/economic growth activities and health/nutrition activities, as top challenges to working across offices. Guidelines and incentives may need to be developed and institutionalized to facilitate effective collaboration between agriculture and economic growth officers and those in charge of health, nutrition, and WASH activities. Such collaboration could facilitate procurement processes, develop more integrated activity designs and monitoring systems, and manage implementation of activities that have nutrition objectives.

Invest Strategically in Partnerships and Capacity Building for Sustainability

Most Feed the Future activities work with partners from multiple sectors at various levels, including public research entities and extension systems of the host country, international, and/or local NGOs, community volunteer networks, and the private sector. Partner mapping exercises might inform the selection of priority groups for long-term USAID capacity strengthening assistance and collaboration. This effort could capitalize on private-sector interests to help strengthen or rejuvenate outreach, extension, and service systems contributing to sustainability of Feed the Future investments.

Annexes

Please download the file at the top of the page to see the annexes.

Footnotes

1 The landscape analysis covered 19 Feed the Future focus countries: Bangladesh, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Nepal, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Tajikistan, Uganda, and Zambia.

2 SPRING also held an AgN-GLEE in Washington, DC in June 2013 to share key points of learning from the regional workshops with USAID/Washington staff,

implementing partners, and other relevant stakeholders.

3 Mali was unable to participate at the AgN-GLEE.

4 Access these field notes here.

5 Gillespie cites Derek Heady, Alice Chiu, and Suneetha Kadihala, IFPRI Discussion Paper 01085, "Agriculture's Role in the Indian Enigma: Help or Hindrance to the Undernutrition Crisis?" (Washington, DC: 2011) (PDF, 813 KB). Earlier significant publications include Corinna Hawkes and Marie T. Ruel, "Agriculture and Nutrition Linkages: Old Lessons and New Paradigms," in Understanding the Links between Agriculture and Health, Series 2020 Vision Focus Brief, series 13, no. 1 (Washington, DC: 2006) (PDF, 66 KB); and World Bank, From Agriculture to Nutrition: Pathways, Synergies and Outcomes (Washington, DC 2008) (PDF, 3.1 MB).

6 The Food for Peace program (P.L. 480), part of U.S. food assistance programs, was established in 1954. P.L. 480 comprises three different programs; Title II of P.L. 480 is the Emergency and Private Assistance Programs that are administered by USAID.

7 Maize and coffee are two of the three value chains the Feed the Future activity in Uganda selected.

8 There has been increased attention on the roles of women in these activities and indicators related to women's empowerment since the initiation of Feed the Future. In 2012, USAID partnered with IFPRI and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative of Oxford University to introduce the Women's Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI). The WEAI measures the empowerment, agency, and inclusion of women in the agriculture sector in an effort to identify ways to overcome those obstacles and constraints. The documents reviewed for this report did not include reference to the WEAI since it was introduced after the development of the multiyear strategies and the design of the Feed the Future activities included in the landscape analysis. The WEAI is now an important tool for Feed the Future to monitor and evaluate activities' impact on gender to ensure that Feed the Future empowers women and supports the essential role they play in reducing hunger and advancing prosperity.

9 The Food for Peace program (P.L. 480), part of U.S. food assistance programs, was established in 1954. P.L. 480 comprises three different programs; Title II of P.L. 480 is the Emergency and Private Assistance Programs that are administered by USAID.

10 The data sources for a number of Feed the Future nutrition indicators (e.g., stunting) include population-based baseline and endline surveys in the ZOI and official Demographic and Health Surveys.

11 The indicators in Box 2 are illustrative. Several are already collected under Feed the Future, such as crop yield, time use, time spent on farm and non-farm labor, feeding practices, and women's control over the use of income. Other indicators may be considered for process monitoring at the activity or project level.

12 Feed the Future has a global strategy to strengthen production and nutritional impact of diverse products. Through its Innovations Labs, Feed the Future is partnering with U.S. universities and developing country research institutes to support a range of solutions to increase dietary diversity and promote more nutritious foods. For more on the Innovation Labs, see: http://feedthefuture.gov/article/feed-future-innovation-labs

13 Case studies cited by the World Bank have shown that smallholder farmers are able to compete in lucrative markets for nutritious indigenous food, even providing dried local fruits for a national airline (FAO 2013).

14 Feed the Future activities in Kenya and Tanzania already highlighted food safety issues; Malawi and Zambia specifically mentioned the importance of addressing aflatoxin contamination.

References

Ag2Nut Community of Practice. 2013. Key Recommendations to Improve Nutrition Through Agriculture. (PDF, 381 KB)

Corinna Hawkes, and Marie T. Ruel. 2008. From Agriculture to Nutrition: Pathways, Synergies and Outcomes. Agriculture & Rural Development Notes 40 (January 2008): 1–4.

———. 2011. Value Chains For Nutrition. 2020 Conference Paper 4. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. (PDF, 1.7 MB)

Korpe, Poonum S., and William A. Petri. 2012. Environmental Enteropathy: Critical Implications of a Poorly Understood Condition. Trends in Molecular Medicine 18:328–336.

Recommended Citation

Du, Lidan, 2014. Leveraging Agriculture for Nutritional Impact through the Feed the Future Initiative: A Landscape Analysis of Activities Across 19 Focus Countries. Arlington, VA: USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project.