SPRING/Mali officially launched in December 2014 with the support of our lead implementing partner, Helen Keller International (HKI). USAID/Mali tasked us with improving the nutritional status of women and children, with a special emphasis on building resilience in the Mopti Region through the prevention and treatment of undernutrition while targeting the critical "1,000 days" of pregnancy and a child's first two years. During the 15 months we were operational in Mopti, the project forged important partnerships with local government institutions and implementing partners (IPs) and provided nutrition-sensitive and nutrition-specific services to over 165,723 community members. SPRING/Mali developed an integrated program and received funding from USAID's health, economic growth, and water and sanitation sources.

Working across 20 focus communes in the Feed the Future zone of influence in the Mopti Region, SPRING utilized community platforms to promote improved agricultural practices, nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices, and key water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) behaviors to project beneficiaries. We employed an integrated approach to ensure that community members received practical trainings and thoughtful engagement that incorporated elements of agriculture, nutrition, and WASH with social and behavior change communication.

SPRING/Mali rolled out three distinct, multi-sectoral activities: farmer nutrition schools (FNS), trainings in essential nutrition actions and essential hygiene actions (ENA/EHA), and community-led total sanitation (CLTS):

- The FNS platform integrated improved behaviors in nutrition, WASH, and nutrition-sensitive agriculture into trainings for local farmers in improved vegetable gardening techniques. By the project's end, we completed four FNS modules, training 500 FNS leaders focused on improved practices for vegetable production and promoted nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices; these leaders in turn trained 5,000 additional farmers from their respective villages.

- To build facility-level and community-level capacity in nutrition and hygiene, we trained over 375 facility-based providers and community health workers and volunteers in ENA/EHA. SPRING supplemented the existing Ministry of Health and Hygiene (MOH&H)-approved ENA training curriculum used in Mali with the hygiene component, ensuring an integrated and comprehensive curriculum.

- SPRING/Mali staff, in coordination with the local sanitation department, helped to establish 4,894 handwashing stations with soap and, having assessed the sanitation needs of more than 50 villages, implemented CLTS in 26 villages, ultimately certifying 20 villages open defecation free (ODF) by project's end.

Our work included routine follow-up visits in each area of work—agriculture, nutrition, and hygiene—to ensure quality and reinforce behavior change. Additionally, each quarter we collected data for our nutrition and WASH indicators, and during the second quarter of FY16, we collected agriculture (Feed the Future) data for the rainy/cold season ending September 2015 and for the cool season through February 2016.

For FY16, USAID/Mali elected not to fund SPRING/Mali further and the project continued to spend carry-over FY15 funding through February 2016, with the final office closure planned for March 31, 2016. All our reports, tools, and data will be passed on to the successor projects identified by USAID, implemented by AVRDC and CARE.

SPRING in Mali

Country Background

According to the 2012-2013 Mali Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), 39 percent of children under five are stunted or suffer from chronic malnutrition and 13 percent of children exhibit low weight for height, or wasting.1 In Mopti Region, nearly half (47 percent) of all children under five suffer from chronic malnutrition, the highest rate in Mali. National statistics show that nearly two-thirds of children are not exclusively breastfeed and only 7 percent of children 6-23 months old receive a minimal acceptable diet. Prevalence of anemia among children aged 6-59 months is at 82 percent, and among women of reproductive age, 51 percent. To help improve agriculture and nutrition outcomes in Mali, the United States Government (USG) named Mali a Feed the Future focus country and reinstated direct foreign assistance to the country after the 2012 military coup. With Feed the Future support, the Government of Mali (GOM) places strong emphasis on building resilience of vulnerable households and making investments to address the high levels of malnutrition and low dietary diversity.2

Mali remains one of the least developed countries of the world:

- Ranks 179 out of 187 on the 2015 Human Development Index

- 39% of children under 5 stunted or suffering from chronic malnutrition

- 22% of households have their own toilets

Mali's lack of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure contributes to the population's poor nutritional status. Only 22 percent of households have their own, improved toilets (e.g., ventilated pit latrines or toilets connected to a septic tank); and without the proper disposal of feces, households are at a higher risk of exposure to pathogens. Handwashing with soap is low in Mali—only 26 percent of households observed in the DHS were found to have handwashing stations. In Mopti, only 21 percent of households had designated handwashing locations, and of those households, only 29 percent had both soap and water available.

To help achieve Feed the Future's goal of reducing the prevalence of stunting in children under five in the zone of influence by 20 percent,3 we complemented the work of existing USAID-funded projects by working with USAID/Mali to select target communes in Mopti that were not already working with other Feed the Future projects.

SPRING/Mali Approach

SPRING/Mali's goal was to improve the nutritional status of women of reproductive age (WRA), pregnant and lactating women (PLW), and children under two years of age (CU2) in the Mopti Region. We did this by promoting the adoption of essential nutrition actions and essential hygiene actions (ENA/EHA), improving delivery of nutrition in health services, increasing the availability and consumption of nutritious and diverse diets through community gardens, and mobilizing communities through community-led total sanitation (CLTS).

To achieve improved nutritional outcomes, we pursued three primary objectives:

- Objective 1: Increase access to diverse and quality foods

- Objective 2: Increase access to quality nutrition services

- Objective 3: Increase demand for key agriculture, nutrition, and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH)-related practices and services

We launched our activities in Mali in December 2014 following a series of stakeholder meetings and the approval of the FY2015 work plan by USAID/Bamako. Under the guidance of our lead implementing partner, Helen Keller International (HKI), the team established a project office in Sévaré, Mopti, and hired 25 staff members with expertise in agriculture, nutrition, and WASH. While our project office and staff were based in Mopti, the Chief of Party (COP) split his time between Bamako and Mopti to ensure strong relations with the Ministry of Health & Hygiene (MOH&H) and Bamako-based partners, while also overseeing operations in Mopti.

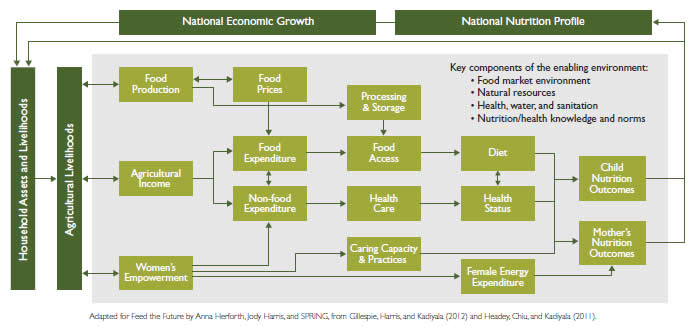

Our approach was based on using agricultural activities (objective 1) as an anchor for entering targeted villages. We integrated activities in nutrition and WASH (objectives 2 and 3) into the same target villages. This approach is grounded in the USAID Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy 2014-2025 and the widely adopted primary pathways for improving nutrition through agriculture: production, income, and women's empowerment.4 (See Figure 1)

Figure 1. Conceptual Pathways between Agriculture and Nutrition

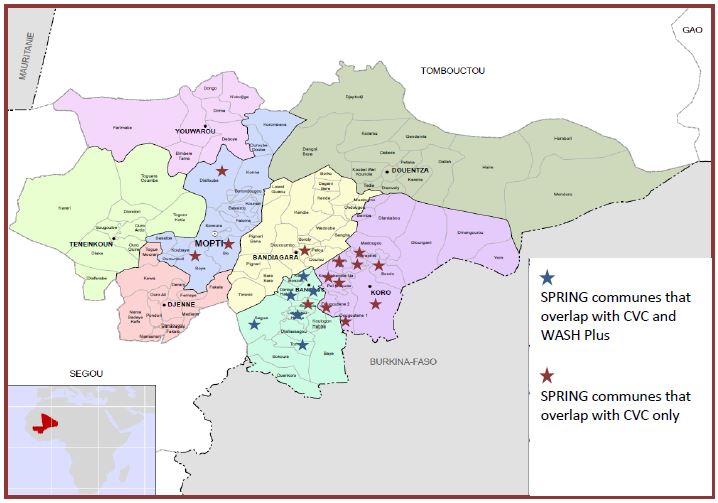

In collaboration with USAID/Mali, SPRING selected four of the eight cercles within the Mopti Feed the Future zone of influence in which to launch our FY2015 activities. The cercles were chosen, in part, on the basis of their relative security (Mopti was and remains insecure) and their proximity to one another.

Within the four targeted cercles, we selected 20 Feed the Future target communes (See Table 1. SPRING/Mali's 20 Target Communes by Cercle). USAID/Mali requested that we concentrate our programming in communes where the CAREUSAID Nutrition and Hygiene Project was not present, but where other relevant USAID Feed the Future investments, specifically the Cereal Value Chain (CVC) Project, the Livestock for Growth (L4G) Project, and the WASHPlus Project were operating (See Figure 2, Map of SPRING/Mali Target Communes).

Table 1. SPRING/Mali's 20 Target Communes by Cercle

| Cercles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communes | Bandiagara | Bankas | Koro | Mopti |

| Dandoli | Bankass | Barapireli | Dialloube | |

| Dimbal Habbe | Bondo | Sio | ||

| Kani-Bonzoni | Dougoutene I | Soye | ||

| Lessagou Habe | Dougoutene II | |||

| Segue | Koporo Pen | |||

| Soubala | Koprokendie Na | |||

| Tori | Koro | |||

| Pel Maoude | ||||

| Youdiou | ||||

Figure 2. Map of SPRING/Mali Target Communes

Within each of the 20 focus communes, we selected five villages (See Annex 3 for the GIS coordinates of all 100 project villages) based on a list of criteria related to our agriculture and nutrition activities. The selection criteria were:

- Criteria related to agricultural activities

- Community interest in agriculture activities and acceptance of SPRING/Mali in the village

- Existence of a water point for easy irrigation

- Existence of agricultural infrastructure (existing community garden)

- Existence of women groups in the village

- Criteria related to health and nutrition activities

- Accessibility to a Centre de Santé Communautaire/Community Health Center (CSCom) and availability of nutrition services in the CSCom

- Availability of community health workers and volunteers

Our catchment area included a total population of 165,723 (23,675 households) (DNSI 2011) and included 33 health facilities (29 CSComs and 4 Centres de Santé de Référence/District Referral Hospital (CSRefs). (See Annex 4 for a list of SPRING/Mali-supported health facilities.)

Approach to Objective 1: Increased access to diverse and quality foods

To improve dietary diversity and promote consumption of nutrient dense foods at the household and community levels, we implemented an integrated community gardening program called Farmer Nutrition Schools (FNS). Based on SPRING's highly successful implementation of FNS in Bangladesh, we adapted the FNS approach in Mopti to:

- Use a farmer field school methodology centered on increasing agricultural production of vegetable crops and income generation through strengthening existing community gardening practices and gardening groups.

- Target training primarily to pregnant and lactating women and women with children under two and their households, but also to include men and other women working in community gardens.

- Support FNS members to cultivate individual plots and to participate in a series of trainings aligned with the seasonal calendar throughout up to three vegetable growing seasons.

The FNS approach promotes good agricultural practices combined with nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices. Examples of this combined approach include growing and consuming nutrient-dense crops, increasing income through cash crops, promoting women's empowerment and integrating water resource management and WASH practices in an agricultural environment. The FNS approach also integrates social and behavior change communication (SBCC) with messages to enhance nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices that link to improved nutrition and WASH outcomes. FNS leaders take their learning back to their villages and, through demonstration and community mobilization, encourage others to adopt improved practices.

We began our effort to adapt the FNS approach for Mopti by taking an inventory of the existing literature related to community gardening in the region. We used the HKI/Mali community gardening manual, the SPRING/Bangladesh FNS curriculum, and materials from AVRDC and IER as the basis for our training modules. To address gaps in knowledge, our staff conducted a rapid assessment to determine local community gardening practices. The assessment5 identified existing varieties of nutrient-dense crops and cash crops that FNS members could produce through gardening activities (See Table 2).

Table 2. Crops Promoted through FNS

| Nutrient-Dense Varieties for Consumption | Cash Crops |

|---|---|

| Okra | Carrot |

| Orange squash (pumpkin) | Beet root |

| Dark leafy greens, such as spinach and cow pea leaves (originally planned as amaranths) | Shallot |

| Moringa tree leaves | Peppers |

| Baobab tree leaves | |

| Papaya tree fruit |

Although orange-fleshed sweet potatoes (OFSP) are a well-known, nutrient-dense variety, these are not currently grown, tested, or approved by the IER in Mali. Therefore, introduction of OFSP would have required importation of vines. Consequently, we chose not to introduce this variety in FY2015.

SPRING identified vendors of high-quality seeds for these varieties. The intent was to purchase seeds in FY2015 that would be provided to FNS participants during the first year. During FY2015, SPRING's strategy was to strengthen input supply systems for the improved varieties of nutrient dense crops through training seed multiplication groups andfacilitating linkages between input suppliers and FNS groups, and, over time, to phase out the input subsidy to FNS members. SPRING ultimately did not procure seeds (see the Challenges section below) and participants in FNS used their own available seeds. As noted in Table 2, we had planned to procure seeds for growing amaranth, which was not widely grown, but because we did not procure the seeds, we promoted continued use of other dark leafy greens.

Our FNS approach emphasizes production, consumption, and conservation of crops rich in vitamin A and iron to address the micronutrient deficiencies that contribute to malnutrition. Our approach also emphasizes income generation through the promotion of cash crops, which can generate income to produce and purchase nutrient dense foods and help cover non-food expenditures, such as health care. Women's empowerment is integral to both production and income pathways. FNS contributes to women's empowerment through targeting primarily female members, but also including men. When women are involved in gardening activities, they can wield greater decision-making power over food produced, consumed, and sold.

While encouraging greater women's involvement, our approach aimed to reduce women's share of physical labor, especially for pregnant and lactating women with children under 2 years of age, by promoting increased participation of men in land preparation and other physically demanding tasks.

To better understand the role of gender in gardening, we completed a literature review of gender,6 addressing the issues of women's empowerment and workload. A follow-up qualitative analysis through focus group discussions would have been implemented in FY16. We had set a target of establishing 25 village savings and loan associations (VSLA) in FY15 to improve women's access to credit. A local implementing partner was selected towards the end of the fiscal year, but SPRING did not award a contract due to the uncertainties of FY16 funding.

In May 2015, we convened a workshop in Severé with local partners, including the World Vegetable Center (AVRDC), l'Institut de l'Economie Rurale (IER), World Vision, Save the Children, and the Ministry of Rural Development (MRD), to exchange best practices and lessons learned on horticulture production and agriculture techniques and technologies. The training briefed p articipants on nutrition-sensitive agriculture concepts and trained them to apply the conceptual pathways to improving nutrition through agriculture. During the workshop, participants developed training materials to promote nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices during FNS sessions.

We created an integrated training package of improved production and nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices. The four FNS training sessions rolled out in Mali included the following topics:

Table 3. Integrated FNS Topics: Sessions 1-4

| Session | Agriculture Topics | Complementary Topic |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Crop selection, plot layout, row-making, planting, and transplanting and nursery management | Increasing knowledge of nutritious crops. Increasing production and consumption of nutrient dense crops. Reducing women's labor by increasing the role of men in land preparation, repairing fencing, etc. |

| 2 | Soil fertility management, pesticide management, water management, farming, and harvest | Handwashing with soap following handling of manure, biological pesticides and other phytosanitary products. Reducing women's labor by increasing the role of men in hauling manure and water. Installation of tippy taps. |

| 3 | Seed multiplication, storage, conservation, marketing, food diversity | Food hygiene during harvest and post-harvest processing Cooking demonstrations promoting preparation methods of a nutrient dense and diverse diet. |

| 4 | Planting and maintenance of tree saplings | Use of moringa, baobab, and papaya |

We implemented FNS sessions 1-3 during the rainy/cold season from July to October and session 4 during the cool season from November to February. In FY16, SPRING planned to develop additional modules covering marketing, business planning, farm management, and household budgeting for nutritional needs. The planned training package7 would have included additional topics, such as post-harvest conservation, utilization of income for food, maintenance of a healthy environment, and nutrition-specific behaviors (see Objective 2 below) during the hot/dry season from April to June when crop planting is limited.

Objective 2: Increased access to quality nutrition services

With Global Health/Nutrition funds from USAID/Mali, we rolled out trainings in ENA/EHA at both the facility and community level. The ENA framework is an integrated package of preventive and curative nutrition actions that includes IYCF, micronutrients, and women's nutrition. The framework promotes a "lifecycle" approach to nutrition and has been implemented across Africa since 1997 (CORE Group 2011). In light of new evidence linking WASH to nutritional outcomes, SPRING added hygiene education to the nutrition actions to create an integrated ENA/EHA package.

Before rolling out trainings to health facility staff and community volunteers, our staff coordinated with the MOH&H to update the GOM-endorsed 2008 ENA national training module for health facility staff and community volunteers to include EHA (See Annex 6 for SPRING/Mali training guides and reference manuals). The integrated curriculum includes the nutrition and hygiene actions listed below and provides health facility staff and community agents with the training and capacity to deliver quality nutrition and hygiene services and counseling.8 At the facility level, the integrated ENA/EHA curriculum helps to build capacity of facility staff, strengthen health service delivery and integrate quality improvement mechanisms for nutrition and hygiene. At the community level, the curriculum builds the capacity of community agents to use interpersonal communication and group facilitation techniques to promote and support the adoption of key nutrition and hygiene behaviors.

The Essential Nutrition Actions (CORE Group 2011)9 are:

- Women's nutrition

- Exclusive breastfeeding 0-6 months

- Complementary feeding 6-23 months

- Feeding during illnesses

- Prevention and control of Vitamin A deficiencies

- Prevention and control of anemia

- Prevention and control of iodine deficiency disorders.

The Essential Hygiene Actions (CORE Group 2015) are:

- Household treatment and safe storage of drinking water

- Handwashing at five critical occasions (after defecation; after cleaning child who has defecated; before preparing food; before feeding child; before eating)

- Safe storage and handling of food

- Safe disposal of feces through the use of latrines and promotion of open defecation free communities

- Creating barriers between toddlers and soiled environments and animal feces.

Objective 3: Increased demand for key agriculture, nutrition, and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH)-related practices

SPRING/Mali integrated WASH activities into both the FNS and ENA/EHA trainings, including education on handwashing with soap and other critical hygiene behaviors. Additionally, SPRING implemented community-led total sanitation (CLTS) activities in key project villages. CLTS is an approach that mobilizes community members to generate collective action in achieving open defecation free (ODF) status.

We followed the 2011 UNICEF CLTS guide, or Guide Pratique de l'Assainissement Total Piloté par la Communauté au Mali,10 to implement CLTS, which includes seven key steps (See Annex 7 for UNICEF CLTS guide):

- Overview/state of the community

- Mobilization/Pre-triggering

- Triggering

- Establishment of sanitation committees

- Identification and training of the local masons

- Post-triggering monitoring

- Evaluation and ODF certification.

We worked closely with local sanitation authorities, the Direction Régionale de l'Assainissement et du Contrôle des Pollutions et des Nuisances (DRACPN), to evaluate which SPRING communities fit the criteria for participation in CLTS. In selecting eligible communities, we evaluated the following criteria:

- Less than 60 percent coverage rate of latrines

- Population between 200-2,000 inhabitants

- Population concentrated rather than dispersed

- Absence of other CLTS partners

- Community has not yet received CLTS

- Community resides within the 100 SPRING target villages

- Community has no recent history of conflict

- Community does not exhibit difficult terrain (e.g., hard rock, flood zones).

In order to select communities that fit the specified criteria, we covered both entire villages and subsets of certain villages (or hamlets/hameaux). Because some villages are much larger than others and exceed the ideal population size for CLTS, we worked in village hamlets where appropriate.

Complementing the implementation of CLTS, we promoted handwashing with soap through the construction of handwashing stations called tippy taps. SPRING field agents and SPRING-trained agents de santé communautaire/community health worker (ASC) and relais communautaires/community volunteers (RC) conducted handwashing demonstrations throughout Mopti using tippy taps and encouraged community members to construct tippy taps at two key locations in the household—near the latrine and near the kitchen.

Interventions and Coverage

SPRING implemented nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive community level interventions across 20 Feed the Future communes in Mopti and supported 33 health facilities (29 CSComs, 4 CSRefs) to improve nutrition services through ENA/EHA trainings. We worked closely with directeurs technique du centre (DTCs) and nutrition focal persons to ensure integration of nutrition and hygiene messages into health contact points such as antenatal care (ANC) and routine visits for mothers of CU2.

Major Accomplishments

Integrated, Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture Approach

To implement our FNS approach in each of the 20 target communes, SPRING signed agreements with the garden's management committees in each project village and established 20 FNS community gardens (1 per project commune) to serve as demonstration plots during the FNS training sessions. The demonstration plots also doubled as individual gardening spaces for participants to practice their learned techniques and cultivate their own crops. Using specific selection criteria, we then identified 500 FNS leaders (418 women and 82 men) from the 100 intervention villages (5 leaders per 100 villages) to build the pool of lead farmers (See Annex 8 for Protocol for Selecting FNS Participants).

We trained all 500 FNS leaders in each of the four modules. Each of those FNS leaders then returned home and trained another 10 farmers in his/her respective village. Thus, the 500 SPRING-trained FNS leaders reached an additional 5,000 beneficiary farmers (4,824 women and 176 men) with nutrition-sensitive agriculture messages through the cascade approach, yielding a total of 5,500 participants trained between June 2015 and February 2016.

Table 4. FNS Training Participants

| Leaders/commune | # of Communes | Leaders Trained | Farmers Trained/Leader | Total Farmers Trained by Leaders | Total Participants Trainied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 20 | 500 | 10 | 5,000 | 5,500 |

The SPRING/Mali program also completed follow-up visits primarily focused on the production and post-harvest stages through two agricultural seasons (the rainy season and cool season). We distributed tree saplings (11,000 moringas, 2,750 papayas, and 2,750 baobabs) to all FNS beneficiaries as a follow-up to training in the fourth FNS module focusing on agro-forestry and the nutritional value of moringa consumption.

FNS Success: SPRING/Mali field agents stressed the importance of reducing women's workload to allow time for nursing children and physical rest. The sessions were well-received and staff observed families adopting the practice.

Although we were unable to conduct an evaluation of the impact of the integrated FNS approach, anecdotal evidence along with observations from follow-up visits suggest that several aspects of the training resonated with participants. Our staff noted that with the development of agricultural techniques, beneficiaries' production improved in both quantity and quality. Additionally, after SPRING agriculture field agents conducted awareness sessions for young boys and husbands about supporting women's work in the gardens, they noticed a positive shift in the families' distribution of work.

To evaluate progress against the Feed the Future indicators, in late January 2016, we developed a data collection methodology and visited a sample of FNS beneficiaries residing in all four districts of the zone of influence. The survey included questions for the rainy/cold season from July to October, as well as the dry season from November to March, and incorporated sections to inform Feed the Future indicators. Findings from this sample enabled us to extrapolate the results to all 5,500 beneficiaries within a 10 percent margin of error (See Table 5) and a 90 percent confidence interval (in line with the Feed the Future indicator guidelines).

FNS Success: Through the promotion of nutrient-dense vegetables, FNS members planted more orange squash. (Staff observation)

For the rainy/cold season, farmers grew the following crops widely: squash, okra, leafy vegetables (namely sweet potato, cowpea, and sorrel leaves), pepper, and eggplant. Of the nutrient-rich commodities planted, squash had the highest gross margin, at $7,137.68 per hectare. Gross margins for okra and leafy greens were $3,698.71 per hectare and $1,590.78 per hectare, respectively. Pepper and eggplant do not qualify as nutrient-rich but had high gross margins: per hectare, $9,401.97 for peppers and $6,558.70 for eggplant.

During the rainy/cold season, one or more improved technologies/management practices were applied on a total of 134 hectares of land. These included cultural practices, pest management, soil-related fertility and conservation, and irrigation. Cultural practices, soil-related fertility and conservation, and irrigation were applied almost universally (133, 132, and 133 hectares of land, respectively), while improved pest management practices covered 111 hectares.

Baseline sales for the rainy season have been established as follows: $82,431.79 for squash (1,386 farmers); $75,050.17 for okra (2,212 farmers); $1,373.64 for leafy greens (260 farmers); $105,200.49 for peppers (1,083 farmers), and $31,941.94 for eggplant (1,039 farmers). Overall, 351,008 kg of squash, 281,230 kg of okra, and 58,657 kg of leafy greens were set aside for home consumption.

FNS Success: « Les différentes formations reçu par le projet SPRING mon permis de connaitre d'avantage le rôle que jouent les différents produits dont nous cultivons et qu'on ignorait leur valeur nutritionnelle. » -- Denis Dougon, FNS leader

During the dry season, significantly fewer farmers planted around their home (12 percent compared to 88 percent in the rainy season). Activity in the community gardens, on the other hand, diminished only slightly, with 56 percent of farmers planting in the dry season in comparison to the rainy season's 67 percent. One or more improved technologies or agricultural management practices were implemented on a total of 31 hectares. Specifically, farmers applied cultural practices, pest management, soil-related fertility and conservation, and irrigation nearly universally: 31 hectares for cultural practices and irrigation, and 29 hectares for soil-related fertility and conservation and pest management.

While many of the farmers selected for the survey planted crops for the dry season, few had harvested and none had sold their yields at the time of data collection in late January. It was not possible, therefore, to calculate and extrapolate results for the gross margin, incremental sales, and nutrient-rich value chain commodity set aside for home consumption indicators.

Table 5. SPRING/Mali Feed the Future Outcomes

| Feed the Future Indicator | Rainy/Cold Season (FY15) | Dry Season (FY16) |

|---|---|---|

| Indicator 4.5.2(2): Number of hectares of land under improved technologies or management practices as a result of USG assistance | Cultural practices: 133 Pest Management: 111 Soil-related fertility: 132 Irrigation: 133 One or more: 134 | Cultural practices: 31 Pest Management: 29 Soil-related fertility: 29 Irrigation: 31 One or more: 31 |

| Indicator 4.5(16): Gross margin per hectare | Squash: $7,137.68 Okra: $3,698.71 Leafy vegetables: $1,590.78 Peppers: $9,401.97 Eggplant: $6,558.70 | N/A |

| Indicator 4.5.2(23): Value of incremental sales (collected at farm-level) attributed to Feed the Future implementation | Squash: $82,431.79 Okra: $75,050.17 Leafy vegetables: $1,373.64 Peppers: $105,200.49 Eggplant: $31,941.94 | N/A |

| Indicator (FTF 4.5.2(7)): Number of individuals who have received USG supported short-term agriculture sector productivity or food security training | 5,500 | 5,500 |

| Indicator 4.5.2.8 (TBD3): Total value of targeted nutrient-rich value chain commodities set aside for home consumption by direct beneficiary producer households. | Squash: 351,008 kg (3248 people) Okra: 281,230 kg (5197 people) Leafy greens: 58,657 kg (1992 people) | N/A |

Increased Access to Quality Nutrition Services

SPRING/Mali initiated ENA/EHA trainings with a training of trainers (TOT) for local government officials and health facility staff, namely directeurs techniques du centre (DTC) and nutrition focal persons. We followed-up the TOT with a training of community agents, including agents de santé communautaire/community health worker (ASC) and relais communautaires/community volunteers (RC). This training served as practice for newly trained trainers and was conducted under the supervision of master trainers. The main objective of the TOTs was to equip participants with the knowledge, skills, and tools to guide them to support MOH staff, health workers, and community actors on ENA/EHA.

Our staff and trained facility health workers, RC and ASC, continued to roll out ENA/EHA trainings via a cascade approach throughout the catchment area. Within SPRING-supported communities, SPRING-trained RC and ASC regularly engaged local support groups and led group discussions on a variety of ENA/EHA themed topics, such as exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding, handwashing with soap, and nutrition for pregnant and lactating women. Through the cascade approach, SPRING was able to go deep into communities and reach more beneficiaries with integrated nutrition and hygiene education than through direct trainings alone.

Facility Level

SPRING/Mali achieved the target of reaching 75 health facility staff from local CSComs and CSRefs in FY15 with training in ENA/EHA. SPRING staff conducted four five-day TOTs for 75 facility staff (24 DTC, 43 chargés de nutrition, 8 district focal persons) from April to August 2015 (Table 6). The TOT provided facility staff with the technical, action-oriented nutrition knowledge and counseling skills needed to support pregnant women, mothers with CU2, and other key family members in adopting optimal nutrition practices. The trainings emphasized the following themes:

- The essential nutrition actions and essential hygiene actions

- Nutrition for women: the intergenerational cycle of malnutrition

- Benefits, beliefs, and myths around breastfeeding and infant formula risks

- Breastfeeding practices from birth to six months

- Nutrition and family planning

- Using images for counseling/observing, reflecting, personalizing, and exploring action (ORPA)

- Negotiation with mothers, fathers and caretakers for the promotion of nutrition for women during pregnancy and optimal breastfeeding practices

- Prevention and management of micronutrient deficiencies

- Complementary feeding practices

- Child feeding when sick and danger signs

- Negotiation with mothers, fathers, caretakers for promotion of complementary feeding and nutritional care of the sick child

- Community support groups

- Integrated management of acute malnutrition (primarily through screening)

- Improved nutrition at community level

- Development of action plans.

Table 6. ENA/EHA TOT for Health Facility Staff

| Training Theme | Location | Number Trained |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Training of Directors and Nutrition Unit Managers in ENA/EHA | Mopti | 8 (6 male/2 female) |

| 2. Training of Directors and Nutrition Unit Managers in ENA/EHA | Bankass | 23 (13 male/10 female) |

| 3. Training of Directors and Nutrition Unit Managers in ENA/EHA | Koro | 24 (23 male/1 female) |

| 4. Training of Directors and Nutrition Unit Managers in ENA/EHA | Mopti | 20 (7 male/13 female) |

Community Level

We achieved our target of training 300 community agents (270 RC, 30 ASC) in FY15 through direct ENA/EHA trainings (See Table 7). Our ENA/EHA field agents led 16 three-day direct trainings to build the capacity of community health workers and volunteers to deliver nutrition and hygiene messages. The trainings emphasized the following key themes:

- Nutrition of adolescent girls and pregnant women and the importance of micronutrients

- Practice of breastfeeding from birth to six months

- Negotiation with mothers, fathers, and caretakers

- Women's nutrition and breastfeeding practices

- Complementary feeding practices and nutrition of the sick child

- The essential hygiene actions (including the construction and use of tippy taps and latrines)

- Homestead food production and nutrition

- Support groups

- Development of action plans.

Table 7. ENA/EHA Training for RC, ASC, and Community Group Leaders

| Training Theme | Location | Number Trained |

|---|---|---|

| 1. ENA/EHA training for RC and ASC | Bankass, Bankass | 20 (9 male/11 female) |

| 2. ENA/EHA training for RC and ASC | Lessagou, Bankass | 20 (12 male/8 female) |

| 3. ENA/EHA training for RC and ASC | Kopora-Na, Koro | 21 (13 male/8 female) |

| 4. ENA/EHA training for RC and ASC | Koporo-Pen, Koro | 22 (19 male/3 female) |

| 5. ENA/EHA training for RC and ASC | Barapirely, Koro | 21 (19 male/2 female) |

| 6. ENA/EHA training for RC and ASC | Dialloube, Mopti | 20 (12 male/8 female) |

| 7. ENA/EHA training for RC and ASC | Segue, Bankass | 20 (12 male/8 female) |

| 8. ENA/EHA training for RC and ASC | Kani Bonzon, Bankass | 20 (14 male/6 female) |

| 9. ENA/EHA training for RC and ASC | Dougoutene, Bankass | 22 (13 male/9 female) |

| 10. ENA/EHA training for RC and ASC | Pel Maoude and Bondo, Koro | 22 (17 male/5 female) |

| 11. ENA/EHA training for RC and ASC | Dandoli, Bandiagara | 20 (9 male/11 female) |

| 12. ENA/EHA training for RC and ASC | Koro, Koro | 26 (20 male/6 female) |

| 13. ENA/EHA training for RC and ASC | Bankass, Bankass | 26 (13 male/13 female) |

| 14. ENA/EHA training for RC and ASC | Sio, Mopti | 20 (14 male/6 female) |

| 15. ENA/EHA training of support group leaders | Bankass/Bandiagara/Mopti/Koro | 100 (4 male/96 female) |

| 16. ENA/EHA training of support group leaders | Bankass/Bandiagara/Mopti/Koro | 100 (2 male/98 female) |

SPRING/Mali-trained ASC and RC extended their reach by creating 200 ENA/EHA support groups in the project cercles. To build the capacity of the support groups, we also trained the group leaders in a direct ENA/EHA training. Through our work with support groups, we were able to reach an additional 12,094 men, women, and children with ENA/EHA practices.

The ASC and RC also organized a total of 1,800 meetings in their respective communities, where they reached 54,554 women of reproductive age (including pregnant and lactating women) and 6,418 children under five with messages on exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding, handwashing with soap, and nutrition for pregnant and lactating women.

We reached an additional 42,500 individuals through radio broadcasts of breastfeeding messages that we developed in collaboration with our partners during World Breastfeeding Week in Mopti. We collaborated with local elected leaders, WASHPlus, CARE-USAID Nutrition & Hygiene Project, the Regional Health Directorate, and health districts in Mopti, Bandiagara, Bankass, and Koro to develop breastfeeding messages to disseminate throughout the week. Our community-driven cascade approach enabled us to increase the number of individuals with access to quality nutrition services and counseling. (See Table 8).

Table 8. SPRING/Mali ENA/EHA Achievements

| Indicator | FY15 Achievement | FY16 Achievement |

|---|---|---|

| Number of individuals trained in child health and nutrition through USG supported programs | 375: 75 DTC; 300 ASC/RC | 200 support group leaders |

| Number of children under five reached by USG-supported nutrition programs | 8,223 | 14,355 |

| Number of women reached with education on exclusive breastfeeding | 55,057 | 49,151 |

Increased Demand for Key Agriculture, Nutrition, and WASH-related Practices

Open Defecation Free Villages

After identifying the eligible villages and hamlets and gaining buy-in from community leaders, SPRING and the DRACPN mobilized 50 villages in CLTS. We then selected the most engaged and motivated communities for triggering. The goal of the triggering process is to generate shared disgust among community members by mapping the defecation areas in the community through "transect walks" and identifying fecal pathways.

Our staff conducted "transect walks" and asked villagers about defecation practices to motivate the community to end open defecation. After the triggering process, SPRING staff made routine visits to CLTS villages to monitor their progress towards achieving ODF status.

Despite weather-related delays, SPRING successfully triggered 26 villages/hamlets in CLTS, ultimately certifying 20 of them (77 percent) open defecation free. Under the guidance of the DRACPN, we waited until the end of the rainy season (June-October) to begin triggering communities in CLTS. During the rainy months, we mobilized the 50 eligible villages and triggered the most qualified villages in September after the rains had passed.

We worked closely with the DRACPN and community leaders to monitor communities as they worked to build and rehabilitate their latrines. Between February 8 and February 21, 2016, a team of evaluators from the DRACPN visited each SPRING CLTS community to conduct a final assessment. In total, SPRING facilitated the repair and establishment of nearly 1,000 latrines across 2,285 households and declared 20 communities ODF (See Table 9 for list of ODF villages/hameaux and Annex 5 for the full list of CLTS outcomes by village).

Table 9. SPRING Villages/hameaux Declared ODF and Number of Latrines

| Cercle | Commune | Village | Hameau | # of Existing Latrines | New Latrines Achieved | Total Latrines |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bankass | Bankass | Sogou Toum | Fangadougou | 3 | 22 | 25 |

| Bankass | Bankass | Sogou Toum | Rakounda | 1 | 28 | 29 |

| Bankass | Bankass | Sogou Toum | Densagou | 3 | 30 | 33 |

| Bankass | Bankass | Kouyentombo | Sarale | 5 | 18 | 23 |

| Bankass | Bankass | Noumoudama | Noumoudama | 50 | 24 | 74 |

| Bankass | Dimbal Habbe | Kounsagou | --- | 20 | 105 | 125 |

| Bankass | Dimbal Habbe | Kounsagou | Badiaganda | 8 | 24 | 32 |

| Bankass | Dimbal Habbe | Kounsagou | Dianweli | 6 | 21 | 27 |

| Bankass | Dimbal Habbe | Kounsagou | Ongonbira | 2 | 39 | 41 |

| Bankass | Dimbal Habbe | Dimbal Habbe | Madina | 3 | 57 | 60 |

| Bankass | Dimbal Habbe | Dimbal Habbe | Manahody | 6 | 23 | 29 |

| Bankass | Dimbal Habbe | Dimbal Habbe | Flandana | 5 | 43 | 48 |

| Bankass | Dimbal Habbe | Sokanda | Sokanda | 10 | 25 | 35 |

| Koro | Koporo-pen | Gomou | Gomou-Kana | 3 | 32 | 35 |

| Koro | Koporo-pen | Koporopen | Komogourou | 21 | 53 | 74 |

| Koro | Pel-maoude | Sogourou | Sogourou-Kanda | 8 | 14 | 22 |

| Koro | Pel-maoude | Pel-maoude | Barakoun | 24 | 19 | 43 |

| Koro | Pel-maoude | Pel-maoude | Monibouro | 44 | 16 | 60 |

| Koro | Pel-maoude | Barali-Niongolé | Wilwal | 19 | 16 | 35 |

| Koro | Koporokendie-na | Temena | Temena | 22 | 26 | 48 |

Handwashing with Soap / Tippy Taps

SPRING helped construct 4,894 tippy taps across 2,447 households during the life of the project (see Table 10). Tippy taps were also established at the FNS community garden sites and at tougounas, public meeting places where villagers gather for storytelling and shared meals.

Additionally, we helped to commemorate World Handwashing Day on October 15, 2015 by organizing a celebration in Koro district in collaboration with WASHPlus and USAID-CARE Nutrition & Hygiene Project. The event helped us organize, mobilize, and sensitize 45 villages of Koro and reach an additional 8,500 villagers with critical hygiene information.

Table 10. SPRING/Mali WASH Outcomes

| Indicator | FY15 Achievement | FY16 Achievement |

|---|---|---|

| Number of households with soap and water at handwashing station commonly used by family members | 1,083 | 1,364 |

| Number of villages supported with CLTS activities | 50 pre-triggered | 26 triggered |

| Number of communities certified open defecation free as a result of USG assistance | 0 | 20 certified |

| Number of people gaining access to an improved sanitation facility | 0 | 5,215 |

Best Practices, Challenges, and Recommendations

Lessons Learned/Best Practices

Collaboration

- By collaborating with the DRACPN, SPRING/Mali more precisely and efficiently targeted and implemented CLTS activities. The DRACPN helped us identify which villages and hameaux were ideal for CLTS implementation. Many villages were ineligible for CLTS as they were already targeted by other projects; others did not meet the criteria the DRACPN recommends for participation in CLTS. Additionally, the DRACPN requested that we delay our CLTS implementation, correctly noting that the rainy season would prevent villages from undertaking construction of new latrines.

- SPRING leveraged AVRDC's knowledge of agricultural practices in the Mopti region by collaborating closely with them when creating our FNS curriculum.

Integration

- The process we used to identify and integrate nutrition-sensitive agriculture messages and ENA/EHA messages into the stages of the agricultural cycles enabled us to identify deeper barriers within agricultural systems and strategies to contribute to better nutrition outcomes through adoption of key nutrition-sensitive and nutrition-specific practices.

- Combining ENA with EHA and training both for facilities and community members through a cascade approach allowed us to promote ENA and EHA behaviors through multiple channels across our targeted communities.

- By involving men and boys in the FNS sessions, we were able to educate them on women's workload, which provided an opportunity to improve norms about gender balance in household work.

Challenges and Recommendations

- We underestimated the challenge of access to water for gardening at the commune level. Although our plans called only for minor improvements to existing wells, our initial assessment did not sufficiently detail the extent of the work needed. By working through the Service Hydraulique, we were able to complete a detailed assessment of the water point rehabilitation needs. Because the identified needs rose to the level of "construction," which is not permitted under the SPRING Cooperative Agreement, we learned only late in FY15 that we would not be able to provide the kind of water access needed to be successful in all of our target communes. Moreover, there was miscommunication with USAID/Mali about the level of support SPRING was to provide. We understood that our assistance was limited to the wells that provide water to the commune-level gardens and did not include potable water within each village.

- We did not procure seeds in time for the June/July planting season due to miscommunication about USAID regulations, which require an environmental mitigation and monitoring plan (EMMP), and due to a change in regulations on procuring seeds, which are a restricted commodity. We did not procure seeds for the October planting season due to delayed communication about FY16 funding; ultimately, permission to procure seeds arrived too late in the season to be useful. As noted above, for both seasons, we relied on seeds already available to farmers, and we substitute procurement of saplings, which could be planted later.

- SPRING missed opportunities to communicate more clearly with USAID/Mali. Unfortunately, our chief of party resigned after only eight months. Although our interim COPs were able to complete many of the project tasks and reach taragets and objectives, we failed to develop a mutually supportive, collaborative relationship with USAID/Mali.

- Based on SPRING's experience, and especially upon the challenges we faced, we recommend establishing project targets after conducting a more detailed initial assessment of the project's catchment area. Many of SPRING's five-year targets, such as declaring 180 villages ODF, were revealed as unrealistic once the project began implementation and learned of particular limitations (e.g., villages ineligible for CLTS, dynamic security considerations). Additionally, by establishing only five-year targets, the accomplishments in FY15 for the number of hectares improved, tippy taps established, and villages declared ODF seem less significant and under-represent the project's efforts and achievements.

Conclusion

In the 15 months that we actively worked to implement integrated programming in nutrition, agriculture, and WASH, SPRING was able to:

- Establish a presence in Mopti, hire 25 local staff, and assess the nutrition-related needs of 100 target villages in 20 communes in the Feed the Future zone of influence.

- Adapt and use the farmer nutrition schools (FNS) model implemented by SPRING in Bangladesh as the point of entry into each community and add nutrition-sensitive agricultural messaging to our training curriculum on vegetable gardening. Through the FNS training we were also able to promote behavior change in hygiene.

- Promote the ENA agenda, adding essential hygiene actions, at both the facility and community levels. For both FNS and ENA/EHA, we used a cascade training approach, leveraging training to 500 FNS leaders to reach an additional 5,000 FNS members. In the case of ENA/EHA, we trained 375 health care workers in facilities and the communities, leveraging these individuals to build a network of more than 200 ENA/EHA support groups, which reached more than 12,000 people.

- Meet our first-year targets for capacity building. In agriculture, WASH, and nutrition, our successes came not from one-off training, but in training over time accompanied by regular follow-up visits by staff.

- Use existing CLTS materials to pre-trigger more than 50 communities (whole villages or hamlets, which was the target for the year), trigger 26 of these, and successfully celebrate the ODF status of 20. Also in the area of WASH, we additionally promoted, through both ENA/EHA and FNS, the creation of tippy taps, resulting in the creation of more than 4,500 handwashing stations in our target villages.

Our primary challenge was the lack of access to water for gardening, so the selection of target villages by the follow-on projects under AVRDC and CARE in the current 20 communes and the 11 remaining communes will be critical. We recommend that it should be based on foreknowledge of the extent to which construction will be required to ensure that water for gardening will be available during two and preferably three planting seasons.

Despite the challenge of access to water for gardening, we made far more progress toward the Feed the Future indicator targets than anticipated during the first year. Our work plan indicated that 5 hectares of gardens would be influenced by our work each season (assuming that 5,500 gardens of roughly 9 square meters are established). But our data indicate that more than 130 hectares were under an improved technique in only the single season of FY15, nearly 25 times the expected number of hectares and our data indicate that farmers did implement what they had learned from the technical assistance SPRING provided.

Having not met all of USAID/Mali's expectations of the project in FY15, funding for FY16 was shifted to other USAID-funded partners. SPRING will provide the successor projects with complete project documentation and materials, so they can build off of the agenda we initiated, to include activites SPRING was not able to undertake, such as the establishment of VSLA groups, provision of quality seeds to promote nutrient-rich varieties, creation of seed multiplication groups, and the promotion of ENA/EHA behaviors through mass media, particularly community radio.

SPRING is grateful to the USAID Mission in Mali for the opportunity to begin this interesting and important work, and most especially we are grateful to our local colleagues and counterparts. We wish the Mission, AVRDC, and CARE every success in the continued déroulement of effective, coordinated efforts to link agriculture, nutrition, and WASH for the people of Mopti Region.

To view the annexes, please download the full report above.

Footnotes

1 Mali Enquête Démographique et de Santé 2012-2013 Rapport de synthèse régionale

2 http://www.feedthefuture.gov/country/mali

3 Feed the Future Country Fact Sheet: Mali

4 For a detailed introduction to the agriculture-to-nutrition pathways, please refer to the Improving Nutrition through Agriculture Technical Brief Series, 2014. Arlington, VA: USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project.

5 All agricultural assessments are summarized in an unpublished draft report, “Maraichage dans la Région de Mopti.” While the report was unpublished, the findings were used to define our agricultural activities. The final draft of the report will be provided to USAID, AVRDC, and Care-PHN as part of a package of SPRING final documentation.

6 SPRING will provide the gender assessment report to USAID, AVRDC, and Care-PHN as part of our package of final documentation.

7 SPRING will provide the FNS training package (which includes the FNS trainer’s guide and the FNS training modules) to USAID, AVRDC, and Care-PHN as part of a package of final documentation.

8 SPRING will provide the 4 ENA/EHA training guides and reference manuals to USAID, AVRDC, and Care-PHN as part of a package of final documentation.

9 http://www.coregroup.org/storage/Nutrition/ENA/Booklet_of_Key_ENA_Messages_complete_for_web.pdf

10 SPRING will provide the Guide Pratique de l’Assainissement Total Piloté par la Communauté au Mali to USAID, AVRDC, and Care-PHN as part of a package of final documentation.

References

CORE Group. 2011. Booklet on Key ENA Messages.

CORE Group. 2015. Understanding the Essential Nutrition Actions and Essential Hygiene Actions Framework.

Direction Nationale de la Statistique et de l'Informatique (DNSI)- Ministère de l'Economie, du Plan et de l'Intégration. 2011. Recensement Général de la Population et de l'Habitat 2009. Mali: Direction Nationale de la Statistique et de l'Informatique. DDI-MLI-DNSI- RGPH-2009-V01.