Nepal’s Multi-sector Plan of Action for Nutrition, 2013-2017 (MSNP) provides a unique opportunity to understand how nutrition policy is translated into action. SPRING’s two-year Pathways to Better Nutrition study drew on qualitative and quantitative data to provide a 360-degree view of Nepal’s MSNP process, including the policy, enabling processes and drivers, prioritization, and funding for nutrition described below.

Findings

SPRING found that Nepal’s MSNP has helped to create an identity for nutrition and increased priority and funding for nutrition programming in Nepal.

Click on the boxes below to read results for each category: policy, drivers, prioritization, and funding.

Understanding the MSNP

Those who didn't know about nutrition are now aware of the importance of nutrition. There is awareness among multi-sectoral partners of nutrition.

– National government stakeholder

The first step in implementing the MSNP was to make sure it was understood and used by all nutrition stakeholders in Nepal. This included not just an understanding of the purpose and content of the MSNP, but also of each stakeholder group's roles and responsibilities for supporting the policy. Finally, it was important for the MSNP to expand or increase knowledge of nutrition to a more multi-sectoral, nutrition-sensitive definition.

Understanding: At the beginning of the study, most stakeholder groups were aware of the MSNP but many were confused about whether it was a specific project, a plan, a set of guidelines, or a framework for planning. There was concern that a separate project would take away from existing sectoral nutrition actions.

During the course of the study, all government and several EDP stakeholder groups were involved in training-of-trainers (TOT) and regional TOTs and MSNP workshops, and most stakeholder groups also attended NNFSS meetings, which seemed to improve their general understanding of the MSNP and the sectors involved in the MSNP. In fact, one group worried there was too much time spent on training as compared to implementation of activities.

Across the three districts SPRING visited, there was good general understanding of nutrition in early 2015 (when the district interviews occurred). The MSNP and related trainings were cited as—

- increasing understanding that nutrition involves all sectors

- sharpening focus on the 1,000 days target groups

- improving awareness that regular inter-sectoral coordination is needed.

By the end of the study, there appeared to be greater agreement that the MSNP was intended as a guiding framework, though a minority (primarily from nutrition-sensitive sectors or EDPs) still misunderstood it to be a project with dedicated funding. Several academic stakeholders and at least one sector ministry also seemed to think NPC was implementing the MSNP and thought they should not do so as a planning ministry.

It appears as if NPC is trying to keep the resources and implement the MSNP, which is not their role. Other ministries should have been used to implement MSNP. Everyone has to play their own role.

– National government stakeholder

Concept of Multi-sectoral Nutrition: At baseline, traditional nutrition actors (such as in the health sector) were most knowledgeable about nutrition and multi-sectoral actions, while many of the groups that were newer to nutrition either thought of it only as a health-related issue or did not think of it at all. By the end of the study a significant improvement was seen in the number of groups talking about nutrition multi-sectorally, crediting the same trainings and meetings mentioned above for their change of thinking. Donors and UN groups indicated that the global nutrition agenda, not necessarily the MSNP, was increasing nutrition awareness in their organizations.

Roles and Responsibilities: At the start, academia, CSOs, and the private sector stakeholder groups asked for greater coordination and clarity on their roles and responsibilities in the MSNP structure. During the course of the study, NNFSS helped develop terms of reference (TOR) for each stakeholder platform. By the end, several groups specifically credited the NNFSS for improving their understanding of the MSNP and their roles, although academia seemed a bit frustrated with the stalled progress on establishment of the academia platform.

Taken together, this evidence points to widespread improvement in understanding of MSNP and multi-sectoral nutrition actions, and is the basis for the rest of our analysis. Knowledge of roles and responsibilities will need to continue to improve to cover all stakeholder groups.

Drivers of Change

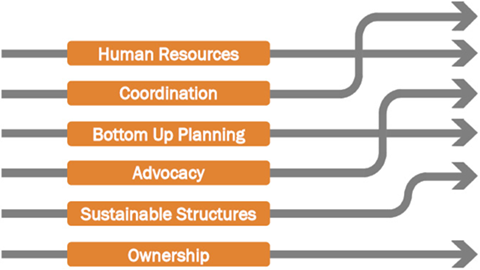

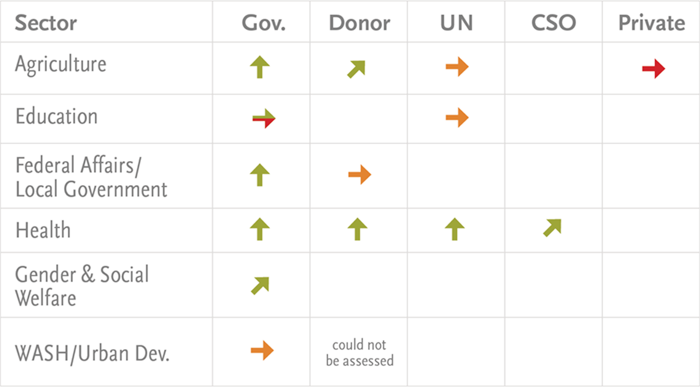

Figure 8. Drivers of Change for Nutrition in Nepal

Certain actions, or "drivers of change," help or hinder the influence of the MSNP on nutrition prioritization and funding. In our qualitative data analysis, we considered reasons given for why the priority and funding of nutrition did or did not improve over time, as well as responses to specific questions about what challenges or enablers stakeholders faced in their efforts to conduct their nutrition activities. Some of these drivers of change aligned with what we hypothesized as key factors at the beginning of the study, e.g., sustainable structures. Others, such as the influence of effective coordination, emerged from the data.

From these data, we identified a set of drivers that were most critical to prioritizing and funding nutrition in this context. In this section, we describe the weight of evidence for changes in each driver that were a result of the MSNP. Figure 8 is a summary of the drivers and the direction of change (no, some, or much improvement) that we observed over the course of the study.

While this list is not exhaustive, it highlights the primary enablers and barriers that effected stakeholders' ability or desire to increase the priority and funds allocated to nutrition activities.

Human Resources

An important driver of change in how nutrition is prioritized and funded is the human resources committed to nutrition. Human resources include all people engaged in nutrition, including clinical and community providers, clinical, policy management, and support staff at every level in every stakeholder group.

Multi-sectoral Coordination of Nutrition Activities

Coordination of nutrition planning, funding, and implementation across sectors, stakeholders, and government levels was also identified as critical to the scaling up of nutrition. This is a "soft" driver in that there may not be concrete signs of change, but changes in behaviors and perceptions as a result of improved coordination can make a large difference when it comes to what is prioritized and funded.

Bottom-Up Planning

The foundation of MSNP planning is the 14-step Nepali bottom-up planning process, defined by the Local Self Governance Act of 1999 (GoN and Ministry of Law and Justice 1999). One of the aims of the MSNP was to create a system at the grassroots level where people from all sectors work together with a district-level nutrition officer to coordinate the process of understanding nutrition problems and identifying sector roles to mitigate them. This system must function if the MSNP is to succeed at the community level.

High-Level Advocacy for Nutrition

Advocacy for nutrition and the MSNP is a very important driver of change because, without it, government and EDPs will not prioritize or allocate funds for nutrition.

If there has been a massive [and convincing] advocacy…that factor will work a bit, otherwise, if [advocacy] has been [inadequate] then the budget funding will not be there.

– National government stakeholder

Sustainable Structures

To maintain momentum for nutrition (or to accelerate progress), structures and processes for planning, funding, implementing, and monitoring nutrition activities must be in place. MSNP stakeholders have an important role in ensuring that nutrition is embedded into existing local and national policy and work planning structures, budgeting processes, and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) systems for the sustainability of commitment to nutrition.

Ownership of Nutrition

Collective national ownership of nutrition via the MSNP goes beyond understanding this plan. It means that each stakeholder group feels responsible for nutrition activities and is invested in the success of the movement. For the government, ownership also means nutrition remains a priority regardless of shifts in national plans and international donor priorities.

From this set of drivers, our evidence suggests the MSNP has had the most effect in improving coordination, advocacy, and sustainable structures. Details are provided below.

The MSNP's Influence on Drivers of Change

Human Resources

From the beginning of the study, three main issues related to human resources for nutrition persisted: inadequate staffing of the MSNP national support structure (within ministries, NPC, and NNFSS), turnover of nutrition focal positions, and lack of and overburdened nutrition implementation staff.

Staffing of MSNP National Support Structure

At the national level, we heard about shortages of staff in the ministries and in the NNFSS and NPC secretariats. We heard that there were not enough nutrition technical staff to keep up with need. For instance, during the time of the study, the Nutrition Unit under the MoH's Child Health Division had only three or four staff. The MSNP called for a national nutrition center; at baseline there were plans for establishing a nutrition center with 50 staff, but by the end of the study there was no progress on this.

There has been some shift in perceptions since 2014, with ministry stakeholders now clearly stating the need for a resource person (within their respective ministries) with technical knowledge on nutrition. The private sector stakeholder group also stated increased interest in gaining technical knowledge on nutrition.

Within the NNFSS (which provides direct support to NPC), a majority of stakeholders stated concern about the lack of government-appointed positions and what that meant for the sustainability of the secretariat. At the end of the study, most stakeholders felt strongly that there has to be government-appointed staff at the NNFSS or at least one full-time government staff whose role is exclusively in support of the MSNP.

There should be permanent secretariat to support MSNP; donors support NNFSS, it is not permanent.

– National UN stakeholder.

Over the course of the study, the NNFSS lost two positions (meaning the staffer had left and there were no plans to replace him/her).

Turnover of Nutrition Focal Positions

From the beginning and throughout the course of the study, staff turnover at almost every level and in every group was identified as one of the biggest barriers for the effective implementation and coordination of the MSNP. The negative effects of this frequent turnover were:

- The new staff do not have the same level of understanding of the MSNP and institutional memory is not transferred to new staff

In the government, those who are assigned in the position will not have known anything, not even an "n" of the nutrition. Then again by the time you make them aware, understand, they will get transferred and you have to restart all over.

– National CSO stakeholder

- New staff may not show the same level of commitment and interest for the MSNP.

- Vacancies and transition in decision-making positions limit what lower-level technical staff can achieve in support of the MSNP. This was noted specifically as an issue that delayed the approval of spending of nutrition funding (Kathmandu Post 2015c).

The frequent turnover of government and some donor and UN positions is due to many factors, including the civil service6 cycle and the reliance on short-term donor-funded staff to support some MSNP components. A number of MSNP focal positions changed over the course of the study. By the end, 43 percent of the ministry nutrition focal positions had turned over, and 5 percent were vacant.

Lack of and Overburdened Nutrition Staff at the Level of Implementation

At the national level and in the three study districts, we heard that availability of staff at the level of implementation was a key constraint. By the middle of the study, stakeholders noted that the district development committee (DDC)—which is responsible for overseeing the MSNP at the district level—was overburdened with multiple priorities. At the end of the study, some national stakeholders even said that the district and VDC staff had been complaining about the extra workload that MSNP placed on their already hectic schedules. During the annual performance review meeting of the Child Health Division (CHD) (FY 2013–14), participants expressed concern that there was no district-level person whose sole designation was to oversee nutrition activities (Paudel 2014).

National government staff stated that there were staff shortages (for nutrition and other activities) in all districts, but particularly in hard-to-reach districts. In Achham, which is just such a district, we heard from district and VDC staff that high turnover, shortage of staff, and lack of desirability for posting were human resource issues relating to the MSNP.

Multi-sectoral Coordination of Nutrition Activities

Multi-sectoral is always good to think about but is always challenging to make it happen.

– National government stakeholder

Coordination is not easy even within the same project or ministry, let alone across sectors and levels. Nevertheless, we saw much progress in this area over the course of the study. In mid-2014, many stakeholders indicated that they were used to working in isolation and that, particularly for EDP and newer government stakeholders, coordination for MSNP was not enough to bring busy people together. In particular, stakeholders highlighted coordination between departments (within the same sector) and inter-ministry coordination as most challenging. However, by the end of the study (late 2015), the perception was that coordination for MSNP and nutrition had improved.

Examples of improvement in coordination during the course of the study:

- By the end of data collection, government, donor, and CSO stakeholders said that they are now working in a consolidated form, especially when finalizing manuals and guidelines related to MSNP.

- During the study period, the three NNFSS MSNP working groups (advocacy and communication, capacity development, and M&E) became more active with regular meetings and follow-up activities.

- Government and donor stakeholder groups felt that coordination at the national level had improved over the course of the study, and many attributed it to the MSNP structures, particularly the placement of NNFSS in NPC and NNFSS's efforts to create active coordination platforms (working groups) across a wide range of stakeholders.

We also heard about areas that need further improvement. Stakeholders remained concerned that because high-level NFS committees did not meet regularly, coordination at the cabinet and parliamentary level was insufficient. Stakeholders were also concerned with the lack of engagement of academia and the private sector, whose involvement remained relatively unchanged over the course of the study.

All of the above generally refers to the horizontal coordination at the national level. But lack of vertical coordination (from national to district and below) was noted as a barrier to implementation of nutrition activities. Some would like to see more coordination during work planning to help prioritize which project to fund. In the three districts that SPRING visited, stakeholders generally had a positive view of the district nutrition food security steering committee (DNFSSC), but the village nutrition food security steering committees did not seem to meet as regularly, mainly due to human resource issues (too few people who could sit on committees, too many committees, and no incentive for them to meet). Concerns about VDC coordination was echoed by national-level stakeholders, who also noted that it depends on the commitment and motivation of the VDC secretary. As of late summer 2015, DNFSSCs had not yet become active in many of the other districts in Nepal (Bhandari 2015).

Bottom-Up Planning

The MSNP calls for a bottom-up planning approach, but several stakeholders were concerned that this did not happen in practice.

14-step planning is there but it is not in practice.

– National government stakeholder

Over the course of the study, sector ministries, NPC, donors, and UN agencies all made several efforts to strengthen the capacity for bottom-up planning for MSNP. Trainings throughout the study period and district support workshops during the first half of the study were conducted to help districts develop their plans for the MSNP. Additionally, sector ministries also provided trainings to their respective district authorities on how to plan for the MSNP. Similarly, UN agencies helped ward, VDC, and districts plan and incorporate nutrition issues into their plans.

Proposals come from the districts but that does not completely get approved because there is political influence at the [national] level. We have to accept that there is a political influence.

– National government stakeholder

Despite these efforts, we noted few measurable changes in perceptions, behaviors, structures, or implementation related to bottom-up planning. By the end of the study, the perception seemed to be that further work is needed in this area. The key constraints related to bottom-up planning for the MSNP that we identified through our qualitative data analysis are listed below.

- Toward the middle of the study, we heard in SPRING's three study districts that DNFSSCs made plans and sent proposals to national ministries but felt that selection of programs was highly influenced by national politics. On the other hand, some of the national stakeholders felt that the districts did not make realistic plans.

- During the same set of lower government interviews in early 2015, various stakeholders from the three VDCs SPRING visited told us that they were not given enough time to make the plans and send up their proposals.

If you visit the people and ask them to prepare a plan in two hours, what can we expect the plan to be?

– District government stakeholder

- Toward the end of the study, some ministry stakeholders mentioned that there were enough general discussions with the local stakeholders, but a lack of nutrition knowledge and lack of access to information (such as routine nutrition data and budgetary information) meant bottom-up planning was still not possible.

Due to limited data, we were unable to assess the perception of the execution of bottom-up planning within the private sector and CSOs.

Advocacy for Nutrition

Over the course of the study, we saw steady improvements in advocacy for nutrition. The diversity of stakeholder groups involved in the improvements was notable. The placement of the NNFSS within NPC signaled leadership by government since early in the rollout of the plan. Further developing high-level advocacy for nutrition was emphasized at the start of and reinforced throughout the study period. By the end of the study, nearly all nongovernment stakeholder groups (except private sector) felt that they had encouraged government to allocate resources for the MSNP, and at least half the stakeholders said that the MSNP had a role in their nutrition advocacy efforts.

Tangible markers of improvement in advocacy found in our analysis during the course of the study include the following actions:

- Government, academic, and UN stakeholders successfully advocated for the budget line item to support the MSNP in 2014.

- The communication and advocacy strategy for MSNP was finalized toward the middle of the study and will be the guiding document for all MSNP advocacy activities.

- The Civil Society Alliance for Nutrition, Nepal (CSANN) started forming district chapters in four of the six MSNP districts toward the middle of the PBN study to advocate for and raise awareness on nutrition and to ensure effective participation of all CSOs in nutrition. They also launched a set of talk shows to spread awareness on the MSNP and nutrition (CSANN 2015).

- The MSNP communications and advocacy working group had discussions about how to mobilize key parliamentarians and policy makers and increase their commitment to the MSNP.

- Stakeholders felt that UNICEF in particular played a key role nationally in advocating at the ministry level and above to strengthen coordination for the MSNP (both national and district) and to understand the constraints related to implementation of MSNP activities.

- Although occurring after the end of the official data collection for this study, a major improvement to ensure district-level advocacy for the MSNP was the development of the TOR for the district support agency.

District stakeholders have also realized the importance of advocacy. During the district support workshop in Kathmandu, which was held soon shortly after our PBN case study baseline, a participant from Achham underscored the importance of advocacy for the MSNP, saying,

Every accomplishment in the district has been because of advocacy campaigns.

– (NPC 2014)

Some remaining barriers to improved advocacy relate to solidifying channels and partners at the highest levels. At the end of the study, some stakeholders were concerned that people who best understood MSNP were often mid-level officers who did not have decision-making authority. Throughout the study, the majority of government and nongovernment stakeholders were convinced that commitment at the parliamentary and cabinet levels was needed to ensure adequate and sustained resources for the MSNP.

Advocacy is major part because it is about high- level authority. If we are able to advocate the situation then it will facilitate to allocate the money.

– National government stakeholder

Sustainable Structures

Building nutrition into existing planning, financial, and monitoring structures is difficult, but our analysis indicates that this is an area in which MSNP stakeholders made significant improvements during the course of the study.

Planning Structures

The big question is of sustainability. Huge resource has come. If the ultimate result will be zero or if it gets back to normal or gets worse after remaining good for some time, then, that's a matter to worry about.

– National government stakeholder

Most of the improvements in this area were at the national level. At the beginning of the study, several national ministry and EDP stakeholders noted that they primarily followed their own sector documents for making decisions about work planning.7 By the end of the study, many ministry stakeholders indicated that nutrition was more institutionalized into sector planning structures and documents. Several EDPs also noted behavioral changes in their organizations that were leading to greater inclusion of nutrition into strategy documents, though they cited the global nutrition agenda as the main reason for this. Tangible markers of institutionalization of nutrition into planning structures include the following actions:

- By the end of the study, four of the six ministries had revised their own sector policies in consideration of the MSNP. Several ministries also included nutrition in their training programs.

- Just after the end of the study, TOR for the district support agency to support MSNP were developed.

At the district and below, however, we heard that further guidance on how to build nutrition into the work planning cycle was still needed.

Financing Structures

At the start of the study, stakeholders had already been advocating for dedicated financial resources for the MSNP. In addition, during our baseline KIIs, several government stakeholders emphasized the need to improve planning, build capacity, and increase transparency for funding. By the end of the study, we saw significant structural and implementation changes related to both of these areas. Tangible markers of institutionalization of nutrition into financial structures include the following actions:

- The institution of the MSNP line item soon after the baseline interviews was a major boost to the financial sustainability of the MSNP.

From this year, separate code for MSNP will be allocated in Red Book

– National government stakeholder

- During the study, several stakeholders mentioned progress toward donor alignment with government priorities (not just for nutrition). The cabinet approved MoF's development cooperation policy, which emphasizes channeling aid through on-budget mechanisms and makes reporting of off-budget funds to AMP mandatory (MoF trends in on-budget aid, 2014/10/24).

because of the policy document the government can now say where they stand in terms of prioritization of different types of aid.

– National government stakeholder

- By the end of the study, stakeholders from both sides felt that there had also been improvements in donor reporting to the AMP8, which gives a more complete picture of support for nutrition and other priority areas:

The reporting is more systematic and donors do more regular reporting.

– National government stakeholder

There have been improvements from the both sides. MoF is more active and we do more regular reporting. It is more systemized.

– National donor stakeholder

Throughout the study, we heard of challenges relating to utilization of nutrition financial resources, due to issues such as late release of budgets and the lack of human resources in the districts. By the end of the study, spending for several projects had improved. At the district level, despite approval of the MSNP line item, some questioned whether it might be more efficient or sustainable to have some percentage of funds set aside for nutrition within the VDC budget itself –

It's like this - there is no need to give separate budget for MSNP. Give it from the budget given to the VDCs. Increase their capacity.

– National government stakeholder

M&E Structures

Less change was seen in M&E structures. We heard from a wide range of stakeholder groups that there was an unmet need for feedback mechanisms and a monitoring system for the MSNP. Although feedback mechanisms have improved via coordination structures (including the new Nutrition and Food Security Portal), the lack of effective reporting mechanisms for MSNP persists.

Key barriers identified by the stakeholders include the following:

- While some ministries (MoAD and MoH) said that they have incorporated some MSNP indicators into their regular management information system (MIS), there is no clear system for regular monitoring and review of all MSNP indicators across sectors.

- Although the draft common M&E framework for MSNP has been finalized, it took a long time to be finalized and even by the end of the study was not fully operational.

- Many government, donor, UN, and academic stakeholders expressed concern during follow-on and end-line interviews that it is difficult to attribute change due to the MSNP, in part because there was no baseline or analysis plan.

It's always anecdotal, OK, MSNP came and then we improved, but [how] much did MSNP improve?

– National UN stakeholder

- At the end of the study, ministries indicated additional concerns about monitoring at the district level because progress reports for MSNP activities go through only MoFALD.

Ownership of Nutrition

At the start of the study, there was wide variation in MSNP and nutrition ownership levels across stakeholder groups. While we did see some positive changes in perception relating to ownership, overall we found little change in this area.

At the beginning of the study, stakeholders emphasized the need for national ownership for MSNP.

If we can internalize the MSNP activities as part of our regular jobs, then we can enhance the ownership

– National government stakeholder

This was reinforced throughout the study. In the final national interviews, several of the more traditionally nutrition-engaged stakeholders said that the government now owned the MSNP as a national document. Keeping in mind relatively limited data for this group, it also appeared that CSO stakeholders were able to establish ownership of nutrition issues via the establishment of CSANN. However, many stakeholder groups that expressed less ownership or engagement at the start of the study continued to express a lack of ownership, because of several barriers.

Key barriers influencing the lack of ownership from different stakeholder groups include the following:

- Sector ministries noted that it was difficult to engage in district activities implemented with MSNP funds, since funding and reporting lines go through MoFALD only. By the end of the study, we heard very mixed responses on this issue: some non-ministry and EDP stakeholders expressed satisfaction with MSNP funds running through MoFALD, while others felt that it should have gone through the line ministries.

NPC should have given the policy guidelines to line ministries and the funds should have been channeled through the line ministries to their respective district offices.

– National UN stakeholder

- Academicians and stakeholders from the private sector also felt that they were unable to have a bigger role in the MSNP because of the delays in setting up official platforms9 for them and because their roles were not explicitly defined. Academicians saw their role in developing an evidence base for implementation, but felt they had not been utilized.

- By late 2015, some national-level stakeholders felt that the lack of government positions on the NNFSS signaled lack of ownership of nutrition at that level.

NNFSS is externally funded by the donors, because of which there is limited ownership from the government.

– National UN stakeholder

- In the three districts we visited, we heard that lack of government ownership is influenced by heavy donor involvement, lack of mandatory objectives and reporting, and lack of nutrition staff.

- Although the private sector signed the MSNP document, all stakeholders including the private sectors themselves felt that they have not owned the MSNP.

We have not been able to do anything and we are staying idle and passive, yet, we are also worried about what we can do, and if you can tell us this is how you should be going ahead, go this way, this is the area where you can work, saying so if you show us the path or create an environment, then next time when you come for a follow up, we can also show some concrete results.

– National private sector stakeholder

The six drivers described above helped us to follow if, how, and why prioritization and funding shifted over the course of the study. The next two sections describe these shifts.

Prioritization

Prioritization is the process of deciding which topics, programs, or activities are most important. Within any organization, prioritization helps administrators determine what will, and will not, be programmed and funded. The level of priority that nutrition receives relative to all other interests determines whether nutrition will receive any attention, and if so, if that attention and corresponding funding will be adequate.

We looked for the following evidence to determine the extent to which nutrition was prioritized by each sector and stakeholder group within a given sector:

- Inclusion of nutrition as a named priority in the sector's strategy documents (or organizational strategy and investment documents for EDPs).

- Creation of a nutrition and/or food security unit, division, or department, or addition of a major nutrition initiative or program.

- Creation of, or increased leadership role in, a nutrition review process within a sector.

- Explicit discussion of or planning for nutrition that would imminently result in one of the above.

Table 1 summarizes the changes we found. Some groups, like the MoH and UNICEF, started with nutrition as a high priority, so even though we didn't see huge change over time, they were continuing a positive trajectory. We also noted the status of nutrition in each government sector strategy at the end of the study.

Table 1. Change in Priority of Nutrition, by Sector (direction of arrows indicates change, color of arrows indicates relative level of priority by endline)

*EDPs work in multiple sectors, but for this analysis they were categorized into those for which they explicitly discussed their involvement in the work planning process. This means responses from some EDPs (such as USAID and the World Bank) are included in the group analysis for multiple sectors.

When compared to responses from earlier in the study, we saw tangible markers of improvement in the priority of nutrition in four of the six ministries, among donors in two sectors, and among UN and CSO partners within the health sector. Within the government, it was notable that three (MoAD, MoFALD, and MoH) of the six government sectors had nutrition as a named priority in the official sector strategy by the end of 2015, and an additional sector (MoE) had named nutrition as a core theme.

At the end of the study, we asked all stakeholders if they noticed any changes from the previous year's work planning in the way in which nutrition-relevant activities were prioritized, and the drivers they thought most influenced that change (or inhibited change, if that was the case). Government stakeholders in all but one of the ministries identified increased coordination as a positive influence on their prioritization of nutrition. MoAD, MoH, and MoFALD variously mentioned factors related to the building of sustainable structures to support nutrition planning, though MoH and MoFALD noted barriers in this driver as well. Increased ownership was also mentioned by MoFALD, MoH, and MoWCSW as influencing nutrition's level of priority in yearly work planning.

Human resources and bottom-up planning were more often described as barriers to increased priority for nutrition. Four ministries mentioned that inadequate number of staff and insufficient nutrition training were barriers, while three ministries mentioned bottom-up planning. Surprisingly, bottom-up planning was most often mentioned as a barrier in cases where the process itself was working fairly well, but the lower level government did not demand nutrition activities, which relates to advocacy.

Among donors and UN groups, we saw an overall increase in the level of priority for nutrition in health. Among donors, nutrition in agriculture also gained status. However, donor and UN groups cited the global nutrition agenda—not the MSNP—as the primary reason for this. We saw no change in donor and UN priority for nutrition in education and local development or in agriculture (among UN groups only). Lack of coordination and ownership appeared to be the primary reasons for this.

Among CSOs, we only had sufficient evidence on those working in the health sector. In that group, we found positive changes in their prioritization of nutrition, and they mentioned that the MSNP had been influential, primarily via its influence on CSO's feeling of ownership over nutrition.

For the private sector, we only had sufficient evidence on those working in the agriculture sector. Here we saw intention to engage at the beginning of the study, but efforts receded by the endline, due to a lack of coordination with the MSNP structure and a lack of nutrition capacity (human resources in the private sector).

In addition to the verbal descriptions, we also documented projects that were being planned specifically to support MSNP, or were being updated with the intention of aligning with the MSNP. Although the majority of the nutrition-related activities were continuations of regular nutrition-related work within each ministry or EDP, or were developed in response to the earthquake, a solid minority of new and continuing activities were related to the MSNP.

Ongoing Projects That Are Working To Align Activities with MSNP

2011–2016 - Suaahara & Suaahara II

Funded by USAID and coordinated with MoH. This community-focused project aims to improve the health and nutritional status of pregnant and lactating women, and children under two years of age. It supports the MSNP and the Hygiene and Sanitation Master Plan 2011-2015, and over time has strengthened support to and alignment with MSNP structures in the districts and below.10

2012–2017 - Sunaula Hazar Din (Golden Thousand Days)

Funded by World Bank and managed and implemented by MoFALD. This project is designed to address the risk factors for chronic malnutrition while aligning with the MSNP.11

2013–2018 – Agriculture and Food Security Project (AFSP)

Funded by the World Bank and managed and implemented by MoAD in coordination with MoH. The project objective is to enhance food and nutritional security of targeted communities in selected locations of Nepal.12

Suaahara mirrors MSNP; it's a huge program with the funding of 72 million. The activities under the upcoming EU funding will be driven by the MSNP. The Golden Thousand Days program is also driven by MSNP. It is clear that MSNP is guiding nutrition programming and planning in Nepal.

– National UN stakeholder

Projects Designed in Support of MSNP

2013–2015: Scaling Up Nutrition Multi-partners Trust Funds (SUN MPTF) for Civil Society Mobilization

Funded by United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and World Food Programme (WFP) and implemented by CSANN. The project focused on assessment and strengthening the capacity of CSOs on the MSNP and the SUN movement for policy advocacy, budget analysis, and monitoring and evaluation in coordination with NPC and NNFSS.13

2014–Ongoing: Multi-sector Nutrition Program (MSNP line item)

Funded by GoN and implemented by MoFALD. Our interviewees described this line item as direct support to roll out the MSNP in the six priority districts in 2014–15 and to expand to 10 districts in 2015–16. A portion of these funds (3 million Rs in 2014–15) were held back for NNFSS support.

2014–Ongoing: Supplementary MSNP Support for Health Sector

Funded by UNICEF and implemented by MoH (comes out of existing UNICEF line item). From budget documents, it appears that the above MSNP line item did not cover health. Instead, UNICEF extended its regular budget support for MoH to cover these MSNP district activities. A portion of these funds was held back for NNFSS support.

Various: Ad Hoc Support for NNFSS Positions and Nutrition and Food Security Portal

Funded by the European Union (EU) and the UN (REACH, WFP, UNDP, UNICEF) in support of NPC. From the interviews we heard that various funders supported all the positions on the NNFSS, with a combination of one- and two-year contracts. These positions are critical to the coordination of the MSNP structure, and also allowed the NFS portal to be built.

2015–2019: Poshan Ko Laagi Haatemalo

Funded by the EU and implemented by UNICEF in coordination with all MSNP ministries. This new project was officially funded in December 2015 (just after the end of our study). Stakeholders and meeting notes described this project as direct support to all MSNP outcomes to combat chronic malnutrition and to foster socio-economic development in Nepal.

In sum, we saw major improvements in the priority of nutrition in all but one government ministry, and among many EDP groups in the health and agriculture sector. In four of the ministries, nutrition is now a named priority or a core theme in the official sector strategy. We documented several major new projects that support MSNP and its goals, and three major on-going nutrition-related activities have aligned themselves with MSNP.

SPRING has followed all funding for the above activities, as well as the continuing regular nutrition-related work within each ministry or EDP. The next and final section describes these funding totals.

Funding

The previous section showed that Nepal has been relatively successful at getting new nutrition activities prioritized and approved. But this alone does not guarantee that these activities will be fully implemented. After a work plan is approved, ministries and EDPs need to ensure that funds are allocated. After allocation, funds must be released to each sector (and sent from each sector to lower government) and these allocations must be spent (spending is otherwise known as expenditure). For each step, bottlenecks may reduce or even eliminate financial support for a given activity.

A negotiation process happens within ministries each year for on-budget nutrition activities (though donors and UN groups also provide on-budget funds, meaning they would also be part of that process). This process starts in September with work planning for local governments, and submission of initial budgets and programs in December and January. The process resolves with the submission of the final national budget by June and authorization by mid-July (Ghimire, Dahal, and Ghimire 2015).

Activities planned by EDPs (donors, UN groups, CSOs, and even the private sector) outside the government Red Book structure (off-budget) are supposed to be coordinated with MoF and relevant sector ministries. This process is primarily the responsibility of the EDP. Off-budget planning and funding may or may not align with the GoN budget calendar, and may in fact follow the fiscal calendar of the donor, UN group, or other EDP. The MoF has increased donor reporting into the Aid Management Portal since the start of the study, with what appears to be regular updating of the projects included. By our measures, about 80 percent of listed projects did not include actual yearly commitments or disbursements, which makes it difficult for the related ministries to incorporate this information into their work- and budget-planning. Fortunately, SPRING was able to extrapolate commitments from total project commitments and length of the project where those data were available.

We will describe the budget estimates and provide the qualitative feedback we received for on- and off-budget allocations, and then on- and off-budget expenditures.

Nepal Date Conversion

In this English version of the final report, we will use the Gregorian (Christian) calendar. For easy conversion, here are the corresponding years in the Vikram Samvat (Hindu) calendar:

| Gregorian | Vikram Samvat |

|---|---|

| 2013–2014 | 2070–2071 |

| 2014–2015 | 2071–2072 |

| 2015–2016 | 2072–2073 |

Allocations

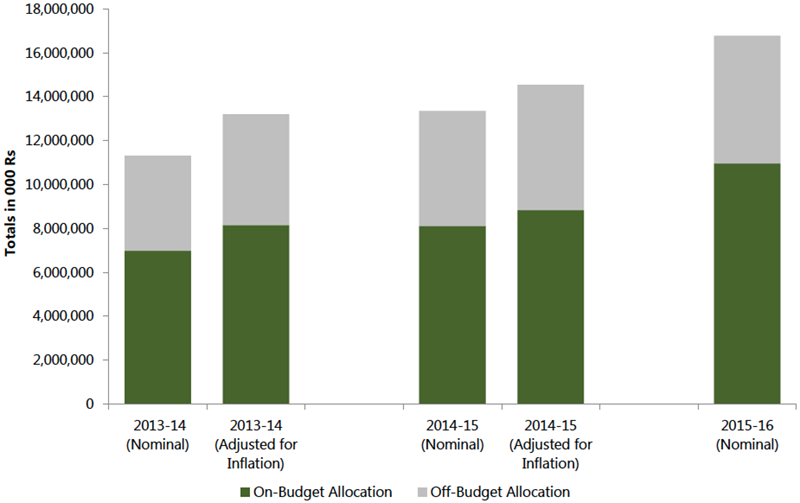

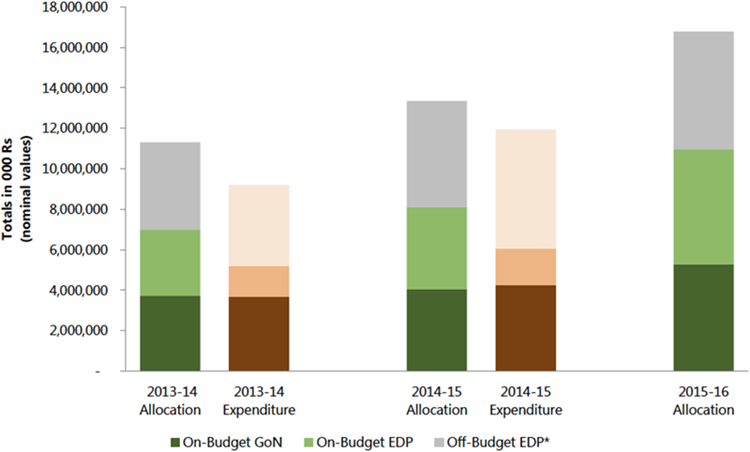

Figure 9 shows the total (on- and off-budget) allocations for the three years included in this study. Combined allocations for nutrition in 2015–16 totaled Rs 17 billion (USD 169 million).

Figure 9. Total On- (Government and EDP) and Off-Budget (All Other EDP) Allocations for Nutrition, 2013–14 to 2015–16

On-budget (green segments) allocations steadily increased between each year. After adjusting for inflation, the real increase was about 17 percent per year, or ~35 percent total between 2013–14 and 2015–16. GoN funds make up about 30 percent of all nutrition allocations over time, but it is important to note that this amount will vary depending on how much of the sub-national grants are counted toward nutrition.

Off-budget funding (grey segment) also grew, though one should be cautious of these figures, given the previously mentioned data issues. From our interviews, it seems that government staff time is used to administer some of these off-budget activities, even though on-budget funding will not record this personnel time. Figure 10 shows how all nutrition funding flows by sector.

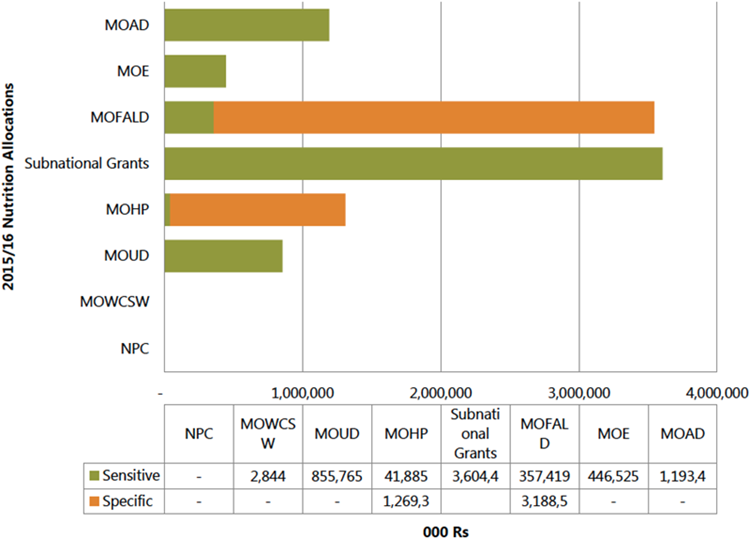

Figure 10. 2015-16 On- (Government and EDP) Budget Allocation for Nutrition, by Sector

* Nutrition activities categorized as specific if they included one of the 10 Lancet nutrition-specific interventions. All other MSNP activities were considered nutrition sensitive.

Sub-national grants were the largest contributor to total GoN allocations. These grants run through MoFALD to all municipalities, districts, and VDCs and provide unconditional funding at that level. These grants were the only on-budget items SPRING was unable to validate, so we used a conservative figure of 20 percent for these three line items. Changing that percentage will create significant changes to total GoN allocations. Since 2013–14, subnational grants have risen steadily, resulting in a 20 percent real increase in this type of funding.

In 2015–16, MoFALD still had the highest nutrition-related allocations, even when sub-national grants were split. The nutrition-specific funding (orange) in MoFALD comes from the Sunaula Hazar Din project and to the MSNP line item for districts. Both of these activities grew over time, Sunaula Hazar Din project exponentially so, resulting in a real increase of about 150 percent between 2013–14 and 2015–16.

MoH provided the next-largest contribution to nutrition-related funding, with about 1.3 billion Rs in 2015-16. Ninety-seven percent of this funding was nutrition-specific. The remainder of the funding was nutrition-sensitive and came from the Integrated Women Health Reproductive Health program and the National Health Education, Information, and Communication Centre. Funding fell over time, with a real decrease of 25 percent, mostly driven by decreases in the Integrated Women Health Reproductive Health program and the Integrated District Health program.

The MoAD is third with just over 1 billion Rs going to 10 nutrition-related activities, which were 100 percent nutrition-sensitive. The largest portion of these funds came from the Agriculture and Food Security Project and the cooperative farming heading. Increases in the Agricultural Research Program, Livestock Development Service Program, and the Agriculture and Food Security Project combined for a real increase of just under 40 percent over the three study years.

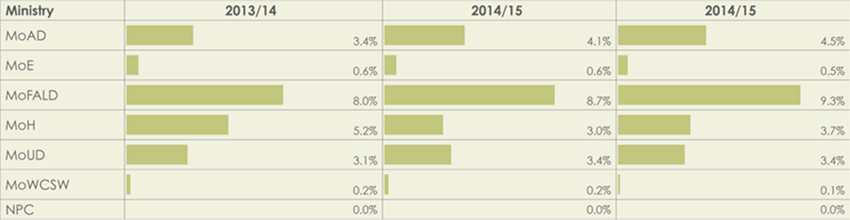

Often advocacy groups will refer to the percentage of total ministry allocation as a benchmark for support to nutrition and other sub-sector priority areas. Table 2 provides these percentages for both years.

Table 2. 2015-16 Nutrition Allocations as a Percent of Total Ministry Allocation

We generally see increases over time in nutrition-related funding as a percent of total ministry allocation for most of the ministries, though MoE and MoWCSW had slight decreases over time. MoFALD (including sub-national grants) again ranks highest in percent of allocation, with about 9 percent of all MoFALD funds going toward nutrition in 2015–16. MoAD had 4.5 percent of funds for nutrition-related activities. 3.7 percent of all MoH funds went to nutrition in 2015–16. SPRING was unable to find any line items related to nutrition for NPC.

Returning to the MSNP-specific projects listed in the prioritization section, we can see their financial contribution to these totals. They supplied Rs 5.3 billion (USD 53 million) to the 2015–16 total, or about 28 percent.

Table 3. Summary of Funding for MSNP-related Projects

| Project Name | Type of Funding* | Est. 2015–16 Allocation, USD | Est. 2015–16 Allocation, Rs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suaahara | Off-budget | $11,000,000 | 1,094,390,000 |

| Sunaula Hazar Din (Golden Thousand Days) | On-budget (MoFALD) | $31,044,195 | 3,088,587,000 |

| Agriculture and Food Security Project (AFSP) | On-budget (MoAD) | $4,212,333 | 419,082,000 |

| Multi-sector Nutrition Program (MSNP line item) | On-budget (MoFALD) | $1,005,133 | 100,000,000 |

| MSNP support for Health Sector | On-budget (MoH) | $162,832 | 15,042,000 |

| Poshan Ko Laagi Haatemalo** | Off-budget | $6,000,000 | 596,940,000 |

| REACH support for NNFSS Positions & NFS Portal | Off-budget | Unclear | Unclear |

| % of total 2015–16 allocation | 28 | Total Allocation | 5,314,041,000 |

*Off-budget is designated by AMP, not by SPRING

**Just approved in December 2015, year allocation is estimated from the average yearly commitment

Only the MSNP line item originates from GoN funds. Sunaula Hazar Din, AFSP, and MSNP support for the health sector are administered by MoFALD, MoAD, and MoH, respectively, but are funded by the World Bank and UNICEF. Suaahara is funded and administered by USAID (with significant involvement from MoH), while UNICEF will implement the EU-funded Poshan Ko Laagi Haatemalo. This means much of the growth in MSNP-related funding is externally funded, which appears to follow a trend across Nepal for the most recent fiscal year (Himalayan Times 2015b). For the remaining ~70 percent of nutrition-related activities, ministry and EDP stakeholders in our qualitative interviews noted that they were not necessarily adjusting activities to align with MSNP, but rather continuing priorities for their own organizations.

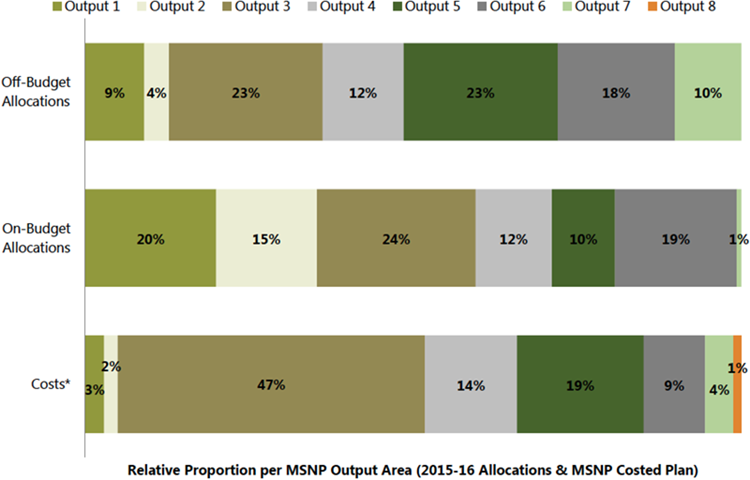

This last point relates to how the balance of funding aligns with MSNP output areas (figure 11). Because the MSNP has projected costs for each output area, we can compare allocations to costs to identify any gaps in, or over-allocation of, funding by area. This information can be used in planning to ensure that ministries and EDPs are aligning priority activities with the MSNP. Overall, allocations exceeded the projected cost for each year. For the last year we tracked, the MSNP projected Rs 1.7 billion would be needed (Rs 1.9 billion once adjusted to 2015–16 dollars). In comparing this to the Rs 10.9 billion allocated on-budget and Rs 5.8 billion allocated off-budget, there appears to be no gap in funding for MSNP.

Figure 11. Total On- (Government and EDP) and Off-Budget (All Other EDP) Allocations for Nutrition by MSNP Output Area, 2015-16

*Source for projected costs: GoN, and NPC (2012).

Recap of Activities in Each MSNP Output Are

Unless an age group is specified, all activities relate to those in the 1,000 days window.

Output 1 activities relate to nutrition policy and planning functions.

Output 2 activities relate to multi-sector coordination mechanisms.

Output 3 activities relate to maternal and child nutritional care.

Output 4 activities relate to adolescent girls' education, life-skills, and nutrition.

Output 5 activities relate to diarrheal diseases and ARI.

Output 6 activities relate to availability and consumption of appropriate foods and women's workload.

Output 7 activities relate to capacity building for nutrition.

Output 8 activities relate to updating multi-sector nutrition information platforms.

Source: Multi-sector Nutrition Plan (GoN and NPC, 2012)

However, this does not mean that allocations by MSNP output area match the cost projection. For output areas 7 and 8, the amount of allocations were neither sufficient to meet costs nor equal in emphasis to the costed plan. Meanwhile, the relative proportion of funding for output areas 1, 2, and 6 was much higher than the expected proportion in the costed plan. For output area 3, allocations were a much smaller percentage (or emphasis) as compared to the costed plan. How much of these funds are spent will also affect how well activities line up with the MSNP output areas.

From this evidence, it appears the allocations are mostly sufficient (as compared to the costed plan) and growing steadily each year, but rely heavily on off-budget EDP funding for some nutrition-related activities, such as those in health and women and social welfare.

Expenditures

We found that for the three years examined, average yearly on-budget spending (green segments) was about 75 percent of total allocation. (Off-budget expenditure cannot be assessed with much accuracy, but some rough estimates are provided in the striped grey bars). Figure 12 shows the comparison of allocations to expenditure for each year.

Figure 12. Total On-(Government and EDP) and Off-Budget (All Other EDP) Allocations and Expenditure for Nutrition, 2013–14 to 2015–16

On average, GoN sector ministries (dark green) spent all of their nutrition-related allocations, though this belies ministry variation. On-budget EDP spending (light green) rates were much lower; just under 50 percent of allocations were spent. Table 4 shows how the average yearly spending rates vary by ministry for all on-budget (GoN and EDP) nutrition-related funds.

Table 4. Expenditure of Nutrition-Related On-Budget (GoN and EDP) Allocations

| 2013-14 | % External | % GoN | 2014-15 | % External | % GoN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoAD | 43 | 70 | MoAD | 64 | 83 |

| MoWCSW | N/A | 88 | MoWCSW | N/A | 67 |

| MoUD | 69 | 55 | MoUD | 54 | 85 |

| MoE | 94 | 67 | MoE | 43 | 69 |

| MoFALD (incl. sub-national grants) | 42 | 112 | MoFALD (incl. sub-national grants) | 41 | 116 |

| MoH | 38 | 83 | MoH | 35 | 63 |

| Avg. national expenditure rate for nutrition allocations | 47 | 99 | Avg. national expenditure rate for nutrition allocations | 45 | 105 |

In both years, sub-national grants were overspent, which contrasts with reports of development funds being frozen for district activities (Himalayan Times 2015a; Jha 2016). These grants are overseen by MoFALD, so they inflate that ministry's spending rate. Without them, MoFALD had one of the lowest expenditure rates, because of low spending on three EDP-funded activities: Rural Community Infrastructure Development Program (WFP), Linking Local Initiatives to New Knowledge & Skills (Helvetas), and Sunaula Hazar Din (World Bank). MoH has the lowest expenditure rates for EDP on-budget funding. This is not limited to nutrition; it appears that expenditure and reimbursement of on-budget EDP funding may be an issue elsewhere (Kathmandu Post 2014).

From our interviews and the news content analysis, two primary reasons appear to be causing the gap in on-budget spending for both GoN and EDPs.

- Delayed release of funds: On the first day of the fiscal year, the finance secretary authorizes spending for all line ministries. The sector ministries authorize spending thereafter, but in some cases this can be delayed for two months or more, reducing the time available to complete the work. This issue appears to effect much of the Nepali budget, so much so that GoN was considering declaring a "budget implementation year," which means that development projects currently underway will not need to get budgets authorized or approved by the NPC, as they attempt to get timelines back on track (Kathmandu Post 2015c). We heard that frequent staff transfers also slowed release of funds.

- Procurement delays: For community-led projects in particular, any given project can be delayed during the bidding and proposal process. For capital projects, this can also be delayed if the detailed project reports have not been developed prior to allocation (Kathmandu Post 2015a). This delays spending, and reduces the amount of time to spend those funds within the fiscal year.

- Earthquake: The effect of the earthquake on spending is unclear. We heard that it impeded implementation of some routine activities, but we heard in other interviews that funds were shifted from under-spent activities to be utilized for disaster relief (Shrestha 2015).

This evidence indicates steady increases in allocations for nutrition across most sources and sectors, although more work could be done to improve utilization and spending of these funds, in particular for on-budget EDP funds. As one national government stakeholder put it,

Resource is not a problem, resource management is the problem.

This problem needs to be addressed at the levels of approval and implementation, and improvements to some key drivers such as human resources and coordination (between GoN and donors in particular). Bottom-up planning will be critical to improving utilization.

Recommendations

What follows are recommendations to overcome barriers and sustain the positive developments past the end of the current MSNP. SPRING developed these recommendations based on the findings from this study and advice and suggestions from the stakeholders.

Click on a recommendation for details.

Although we documented significant progress in understanding of the multi-sectoral causes of malnutrition at the national level, significant gaps in understanding remained in the three districts and VDCs we visited. We heard from the national ministries that some VDC sector officers did not demand nutrition activities following the bottom-up process, e.g., in the urban development and education sectors where physical infrastructure was more desirable.

GoN and partners can continue investment to increase awareness of multi-sectoral nutrition through multiple channels (mass media, household, etc.) for all target groups at the community and local levels. Local-level policy and decision makers are key assets to help increase understanding of the importance of nutrition across multiple sectors, especially related to urban development and education. Their increased awareness will help generate demand for nutrition in the local planning process.

During the course of the study, more than half of the national-level nutrition focal staff people who we interviewed turned over. By the end of 2015, four positions at NPC and NNFSS went vacant. Turnover also affected EDP nutrition staff. This turnover, combined with low technical capacity in nutrition among some ministries, strained national efforts to convene for the MSNP. In three districts and selected VDCs, government staff reported that nutrition activities were hard to support because of staff shortages, especially in hard-to-reach areas.

The GoN (and EDPs) should ensure continuity and institute handover protocols to keep institutional MSNP memory in each ministry and organization. The GoN could do this by building nutrition curriculum into the civil servant training period. NPC began working with the Ministry of General Administration and the Ministry of Finance to reduce transfers and create new positions for nutrition officers, and this could result in concrete guidelines in this area. At the district and VDC levels, we suggest creating a designated focal person for nutrition activities; GoN can discuss the feasibility of financial incentive schemes to keep those positions filled in hard-to-reach areas.

Educating parliamentarians, lawmakers, and other high-level leaders about the importance of nutrition should be a prime agenda items for MSNP. In the original support structure plans, provisions for parliamentary and cabinet-level sub-committees and a high-level (Ministry Secretary-level) nutrition and food security steering committee (HLNFSSC) were made. Yet we were told that the parliamentary and cabinet-level sub-committees may not have ever met, and the HLNFSSC only met once or twice in the last two years.

Revitalizing the HLNFSSC and activating the sub-committees for advocacy on the MSNP could increase government ownership within the sector ministries. This could also motivate EDPs and the private sector to increase alignment of activities with the MSNP, especially if advocacy by these committees could link nutrition to the country’s future economic development. In addition, creating better communication among all levels of nutrition and food security committees will help unify advocacy efforts from the HLNFSSC down to the VDCs

The MSNP support structure must include all stakeholders at every level. In our interviews, we were told that academia and the private sector had, so far, had much less engagement in MSNP coordination activities. Formal recognition of the academic coordination platform within the NNFSS had stalled, and a coordination platform for the private sector had not yet been formed by the end of the study.

Efforts to activate the academic platform should restart. In addition, academic stakeholders sit on the HLNFSSC, so restarting this convening mechanism means academia could provide the evidence needed to fuel advocacy at the highest level. The private sector will need a clear business case for engaging, which could be developed by reframing the argument for nutrition in terms of increased labor productivity and improved market opportunities for products that align with the national nutrition standards. Creating a private sector coordination platform would facilitate this discussion.

By the end of the study, an MSNP monitoring and evaluation (M&E) framework was in final draft after review by all sector ministries, but approval stalled, possibly due to vacancies in the national MSNP support structure. Yet stakeholders at every level reinforced the need to coordinate monitoring data and evidence on the impact of the MSNP on nutritional indicators.

The GoN will need to approve and implement the draft M&E framework as soon as possible. The NPC may want to consider including nutrition financing indicators in this final plan. National ministries, districts, and below need an accompanying set of implementation guidelines to define exactly how sectors and districts are to collect this information. Technical assistance may be needed to pull all sector nutrition indicators into a national reporting structure.

Bottom-up planning is not unique to nutrition, but it is critical for understanding which nutrition programs will work best in each community. While some stakeholders felt that bottom-up planning was working for MSNP activities, others felt that bottom-up planning had been in name only and not in practice. Indeed, various stakeholders from three VDCs told us that they were not given enough time to make the plans and send up their proposals.

Central ministries, CSOs, and EDPs should build capacity to strengthen the planning process at the community level. This includes creating clear implementation guidelines on how to plan, budget, and conduct MSNP-related nutrition activities. As capacity is strengthened at the local level, the national ministries need to consider the local plans and proposals seriously. Where possible, the districts should be given some unconditional funding to help them fulfill local needs. Within the districts, the district development committee should lead efforts to plan for MSNP activities. Bottom-up planning schedules should give the VDCs sufficient time to assess community needs.

While the GoN—via the MSNP line-item funding—and EDPs (for example, USAID, the World Bank, and UNICEF) have made significant progress in rolling out the district nutrition and food security steering committees in the six MSNP priority districts, much work is still needed to ensure that every VDC in those districts has an operating nutrition and food security committee. In addition, the new MSNP expansion districts—28 are listed in the MSNP—will need to develop nutrition and food security committees. We heard from every level that this was both a serious challenge and an absolute necessity for the long-term success of the MSNP. These committees are excellent platforms for all stakeholders to share data, generate evidence-based programming, and coordinate bottom-up planning for nutrition.

To move beyond the initial creation of the local committees, the human resource constraints noted in recommendation #2 must be reconciled. In addition, committee membership should be spread out to ensure that the same people at the VDC level are not overburdened with multiple meetings for different programs. EDPs should also engage and support VDC committee members—we heard from stakeholders in one VDC in Parsa that the Sunaula Hazar Din project has recently made progress in activating the VNFSSC. Finally, we heard anecdotally that the proposed district support agency could be another channel to support these committees.

Evidence indicated that while EDPs—particularly donors and UN groups—gave substantial support to nutrition activities, they seemed to primarily follow their own global agenda for nutrition. While many referred to the MSNP for planning, it was often a secondary or tertiary document. This was also true of many (but not all) EDPs in the districts and VDCs we visited. Some partners, like the private sector, did not make any reference to the MSNP.

We heard from donor and UN stakeholders that they see increased coordination as the biggest potential benefit of the MSNP. Because of the amount of funding coming from these sources in Nepal, it is essential that these organizations communicate their plans, not only with the government but also with other EDPs. Increased coordination of nutrition activities is just as important for ministries, the private sector, and CSOs. It is, therefore, critical to embed all stakeholders into the MSNP coordination structure to ensure they are active and engaged.

At the national level, GoN could use the existing national nutrition secretariat and the national nutrition group (NNG) to encourage regular sharing of the draft sector and EDP plans for nutrition activities early in the budget cycle. At the local level, EDPs could work closely with the district and VDC committees to decide how to add more activities based on locally identified needs to their programs.

MSNP support structures—such as the NNFSS, other steering committees, and NPC—are essential for oversight and management for nutrition planning in Nepal. These committees operate from the national to the VDC level. The evidence demonstrated that these structures were well received at the national and district levels—for instance, many stakeholders cited the NNFSS as helping them understand the MSNP, increasing their knowledge of multi-sectoral nutrition, helping them coordinate with other stakeholders, and learning how to prioritize nutrition. Currently however, all NNFSS positions are externally funded. At the time of our interviews, the nutrition and food security committees in our three VDCs had been formed but had never met.

Nationally, the GoN must start providing dedicated funds for NNFSS to ensure its continued existence, and/or greater funds for NPC staffing and involvement in coordination activities. GoN could provide additional dedicated nutrition funds to the VDCs (via the VDC block grants or another mechanism), or require that some percent of existing VDC block grants be used for this purpose to activate the below-district-level nutrition and food security steering committees.

Footnotes

6 Civil servants are entitled to a transfer after two years. In reality, however, turnover occurs before the two years are over, sometimes as soon as three or four months.

7 This was also attributed to differences in the timing of planning cycles across the sectors.

8 Some stakeholders noted issues of double reporting in AMP when donors give to UN agencies (both UN and donors would report).

9 The academia platform has not received official recognition and their TOR has not been endorsed.

10 https://www.usaid.gov/nepal/fact-sheets/suaahara-project-good-nutrition

11 MoFALD. Community Action for Nutrition Project: Sunaula Hazar Din. Project flyer.

12 http://www.foodandenvironment.com/2013/10/agriculture-and-food-security-project.html

13 UNDP, FAO. 2014. MPTF Office Generic Annual Programme 1 Narrative Progress Report – Year 2014.