Fiscal Years 2015-2017

Executive Summary

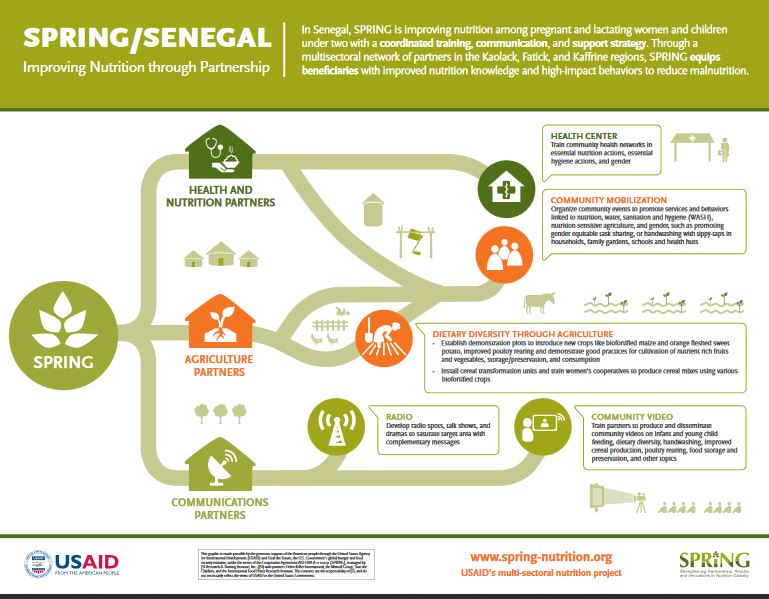

The Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project launched a two-year program in Senegal in November 2015 focused on creating, testing, and learning from local partnership approaches to improve the nutritional status of pregnant and lactating women and children under two years of age. SPRING/Senegal employed a multi-sectoral approach to tackling malnutrition, conducting activities across agriculture, health, hygiene, and gender. The project worked closely with established organizations, platforms, and networks in our target regions of Kaolack, Kaffrine, and Fatick. We fostered partnerships and opportunities for collaboration with U. S. Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded programs and other organizations working across sectors to increase demand for and access to improved nutrition inputs and services, by promoting both nutrition-specific practices and nutrition-sensitive agriculture.

SPRING used a variety of capacity building and social and behavior change communication (SBCC) approaches to raise nutrition awareness among partner organizations and their clients. To accelerate adoption of essential nutrition and hygiene actions and promote good nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices, we developed a set of practices and behaviors aligned with partner programs and tailored to local conditions and needs. In addition to directly building program partners’ capacity, we also introduced a range of SBCC activities to reinforce work with collaborators and reach a broad audience across the target regions.

We worked with six community-based radio stations to create 15 radio spots that were broadcast over 14,000 times. We developed 30 interactive radio programs to encourage good nutrition-related practices and stimulate demand for nutrition services. SPRING reached over 900,000 people with nutrition messages through radio. We also trained local radio station staff to produce 10 local community videos and formed 3 local video production teams capable of producing community videos over the long term. We drew the content of the videos, radio spots, and radio programs directly from findings of our formative research to promote more nutrition-sensitive agricultural practices, proper hygiene, and more gender-sensitive behaviors. We also trained producer network field agents and community volunteers to disseminate these locally produced videos across 100 villages and facilitate discussion sessions on the topics featured in the films.

To meet the demand created through the SBCC interventions, we helped local agricultural partners increase their capacity to pursue nutrition-focused agricultural practices. SPRING accomplished this by providing partners with a combination of workshops on nutrition-sensitive agriculture for members of community-based producer networks. In addition, SPRING utilized demonstration plots to promote the cultivation, harvest, storage, consumption, and marketing of nutrient-rich crops such as Obatampa maize, bio-fortified millet, orange-fleshed sweet potatoes, and diverse nutrient-rich vegetables. We also collaborated with partners to increase protein intake through improved village poultry practices to increase consumption of chickens and eggs. In addition, we installed model micro-gardens, complete with tippy-tap handwashing stations, and trained 240 women and 25 field agents, who in turn trained and supported approximately 2,700 women to plant and maintain their own micro-gardens across 90 villages. SPRING strengthened the coverage and capacity of agricultural suppliers by mobilizing community-based service providers to increase access to inputs (such as seeds, saplings, fertilizers, and protective gear).

SPRING’s work in the health sector centered on a collaboration with the Senegalese government’s Cellule de Lutte contre la Malnutrition (CLM). The CLM is attached to the Prime Minister’s Office and is charged with articulating and coordinating a multi-sectoral strategy to reduce malnutrition in Senegal. Through this relationship with the CLM, SPRING worked with some of CLM’s implementing agencies, including Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Être Familial (ASBEF), ChildFund, and Plan Senegal.

Evidence indicates that increasing women’s decision-making capacity, coupled with an increase in income and free time, positively influences family nutrition. As such, SPRING promoted gender-sensitive best practices throughout its project activities. SPRING identified households where husbands demonstrated greater involvement in household chores and included their wives in decision making to serve as role models, or “champion couples” within their communities. These champions were recognized and celebrated in their community for their progressive initiative, which served as a model for others to consider adopting these behaviors. Further, to reduce the amount of time women spent husking and grinding cereals manually, the project donated cereal processing machinery to agricultural partners, which not only reduced women’s workload but also provided them with the ability to earn income. The project focused on improving hygiene in communities by promoting handwashing and the use of simple, water-saving handwashing stations called tippy-taps. These tippy-taps increased handwashing at significant points around the compound, including near latrines and kitchens and at the entrances to household gardens, chicken coops, or sheep pens. SPRING also facilitated the creation of hygiene monitoring units, which were groups of influential community members who monitor the state of hygiene within their communities and promote the uptake of good hygiene practices.

Our successful collaboration with value chain actors, the CLM, and women’s horticulture groups, among others, showed that they are willing to invest their own resources and engage as promoters of nutrition-sensitive agriculture in their communities. These partnerships were crucial to the successful implementation of the project. This report examines the ways SPRING collaborated with partners from different sectors and the lessons and recommendations drawn from these experiences. The infographic on the next page illustrates some of the key activities we conducted with our partners (see Figure 1).

SPRING in Senegal

Background

Despite the high levels of political and social stability that Senegal has enjoyed since independence, 46.7 percent of Senegalese people live below the poverty line, and Senegal’s rate of food insecurity stands at 17 percent. While the country has seen a drop in the prevalence of underweight, wasting, and stunting in recent years, these indicators still stood at 15.5 percent, 7.8 percent, and 20.5 percent respectively in 2015 (World Bank 2017). Poor nutrition and health practices play an important role in the etiology of stunting. Only 38 percent of infants are exclusively breastfed for 6 months; in rural areas, only 12 percent of children ages 6-23 months meet minimum dietary diversity, and only 7 percent receive a minimum acceptable diet (ANSD 2013). Lack of access to affordable, nutrient-dense foods is also a critical barrier to good nutrition.

Suboptimal health practices among women exacerbate undernutrition. Only 39 percent of rural women receive the recommended four antenatal visits, while only 20 percent are given deworming treatment. Fewer than half consume the recommended number of iron-folic acid (IFA) supplements to improve birth outcomes (ANSD 2013). Nationally, anemia affects 71 percent of children under 5 (CU5), 54 percent of women of reproductive age (WRA), and 61 percent of pregnant women (USAID 2016). Half of these anemia cases are likely attributable to iron deficiency.

Social norms and customs also dictate how children are fed. For example, colostrum—the first milk—which is rich in nutrients and immune system boosters, may not be fed to the newborn out of fear that it causes jaundice. It is also common practice to give infants water and traditional pre-lacteal foods, which reduces consumption of breastmilk and introduces pathogens that can cause diarrhea (62 percent of children receive other liquids in addition to breast milk, mainly water) (ANSD 2013). As a result of these and other poor practices, when complimentary foods are typically introduced around 6 months of age, the rate of stunting doubles every 3 months until the age of 24 months (ANSD 2013).

Poor hygiene practices in Senegal also contribute to stunting. Approximately one-third of rural households collect their drinking water from unimproved sources, and 62 percent of rural households do not take steps to purify their drinking water. Handwashing data are hard to find, but an observational study by the World Bank indicated that only 31 percent of the population practice handwashing after defecation (Urban Water and Sanitation Project 2010). Such poor practices lead to the high prevalence of illness and environmental enteropathies that contribute to stunting.

Project Overview

At the request of USAID | Senegal, SPRING worked from November 2015 through October 2017 to support the mission’s goal of reducing stunting by 20 percent in children in the Feed the Future zone of influence (ZOI) and improving the nutritional status of women and children (the Country Development Cooperation Strategy’s Intermediate Result 4) (USAID 2017). According to USAID, given the wide-ranging determinants of nutritional status, programs that seek to sustainably improve nutrition outcomes must tackle not only nutrition-specific factors related to immediate causes of malnutrition, such as infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices and micronutrient fortification, but also nutrition-sensitive factors related to underlying causes of malnutrition—for example, water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) and improved agriculture techniques (USAID 2016). Per the Mission’s guidance, SPRING approached the short implementation period with a focus on learning, capturing and sharing lessons learned about working in partnership with local organizations and programs across sectors to strengthen nutrition capacity and outcomes.

Figure 2. Map of SPRING Target Regions in Senegal

SPRING’s specific goal was to improve nutrition among households in target areas by increasing coverage of a package of nutrition-sensitive and nutrition-specific interventions. The project had two objectives to meet this goal:

- Increase awareness of, and demand for, good nutrition-related practices and services

- Facilitate access to key inputs and services essential for good nutrition

To achieve rapid results and build locally-owned sustainable solutions, SPRING worked closely with existing organizations, platforms, and networks in the target regions, and through them built capacity and momentum for improved nutrition in Senegal. SPRING sought partnerships and opportunities for collaboration with USAID-funded programs and others, in multiple sectors, to promote nutrition-specific practices and nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices.

Interventions and Coverage

SPRING prioritized three of Senegal’s fourteen regions for its interventions. The three regions, all within USAID Senegal’s Feed the Future ZOI, were Kaolack, Fatick, and Kaffrine (see Figure 2). These regions share several characteristics and conditions that made it logical for SPRING to work there: (1) similar agro-ecological conditions and growing seasons; (2) many of the same health and agriculture projects and collaborators; and (3) logistical feasibility and access. The nutritional status of CU5 in these regions is also precarious, with the following stunting rates: Kaolack (19.6 percent), Fatick (20.5 percent), and Kaffrine (26.8 percent). Table 1 below shows the population of each of the target communes within the three project regions (Feed the Future 2017).

Table 2. Prevalence of Anemia and ANC and IFA Coverage in DRC among Women 15–49 years, 2007

| Region | # of ZOI Target Communes | Estimated ZOI Communes Population | Est # House- holds | # of WRA | # of PLW | # of CU5 | % of CU5 Stunted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatick | 9 | 294,627 | 32,736 | 79,549 | 31,820 | 44,194 | 22% |

| Kaolack | 17 | 575,103 | 63,900 | 155,277 | 62,111 | 86,265 | 29% |

| Kaffrine | 16 | 424,421 | 47,157 | 114,593 | 45,837 | 63,663 | 38% |

| Total | 42 | 1,294,151 | 143,793 | 349,419 | 139,768 | 194,122 | - |

To calculate the estimated number of households, we divided the estimated ZOI communes population by nine people per household, based on 2010 census data. The number of WRA was estimated at 27 percent of the total ZOI commune population (Index Mundi 2014), while number of PLW was estimated at 40 percent of the WRA. The number of CU5 was estimated at 15 percent of the total ZOI communes population, also based on census data. We retrieved data on stunting of CU5 from the Senegal Demographic and Health and Multiple Indicators Survey (ANSD 2012).

Approach

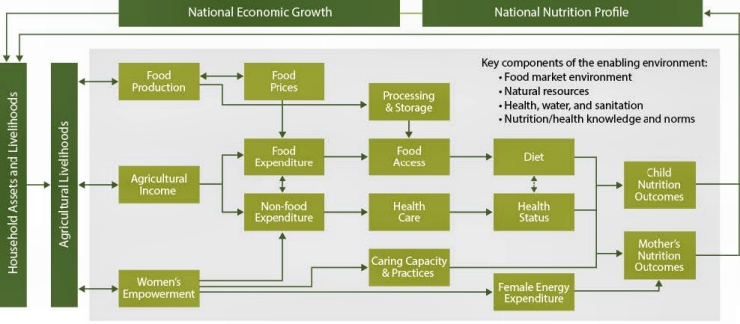

To reduce stunting and improve the nutritional status of women and children, SPRING implemented a dual strategy of scaling up proven nutrition-specific interventions, including essential nutrition actions (ENA) and essential hygiene actions (EHA), and promoting contextually appropriate nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices and access to related services and inputs. Together, the nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive activities implemented created synergies to contribute to a reduction in the rate of malnutrition in Fatick, Kaolack, and Kaffrine regions. At the onset of the program, SPRING conducted formative research to identify barriers to proper nutrition, gender- sensitive best practices, and good hygiene in communities. We used the information collected from this research to develop contextualized programmatic recommendations, which in turn informed activities to prioritize with partners from each sector. 4 | Senegal: Final Country Report Figure 3. SPRING’s Conceptual Pathways between Nutrition and Agriculture SPRING/Senegal’s design proposed two objectives toward reaching our overarching goal of improved nutrition among households in the SPRING intervention area:

Objective 1: Increase awareness of, and demand for, good nutrition-related practices and services

Objective 1 focused on implementing an integrated social and behavior change communication (SBCC) strategy to increase knowledge and uptake of desired practices using a range of communications and outreach mechanisms, including, but not limited to: 1) adaptation and use of education and/or extension approaches already being promoted by partners; 2) use of mass media; and 3) use of community video. SPRING worked to build the capacity of existing programs and collaborating partners to promote key nutrition-related behaviors identified as priorities through formative research conducted at the start of the program.

SPRING’s SBCC approach ensured that:

- the total number of improved nutrition-sensitive agriculture and nutrition-specific practices were realistic, and fit within collaborating partners’ activity plans and approaches;

- training, advocacy, media, and other communication materials were tailored to the project context, and the different audiences;

- target groups received consistent, clear messages and demonstrations that reinforced each other across project activities in an integrated and phased way;

- the project fostered an enabling environment for the improved practices to support desirable change.

Objective 2: Facilitate access to key inputs and services essential for good nutrition

SPRING’s activities under Objective 2 complemented the demand created in Objective 1. In line with the Conceptual Pathways between Nutrition and Agriculture framework (see Figure 3), the nutrition-sensitive agricultural practices promoted by SPRING aimed to diversify food production, increase

Figure 3. SPRING’s Conceptual Pathways between Nutrition and Agriculture

agricultural income, and increase women’s empowerment. We sought to build the capacity of existing service providers, networks, community-based organizations, and volunteers to promote the targeted practices appropriate to the area and audience. Because capacity building and training alone are not sufficient to ensure the ongoing use of many of the ENA, EHA, and nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices that were promoted, SPRING worked with collaborating partners to use a market-driven approach to increase availability of quality goods, inputs, and services. Activities were further enhanced through SBCC and existing information systems to sustainably embed nutrition-related messages where possible and to promote the value of adopting nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive practices. SPRING interventions were geared towards creating household demand and strengthening the knowledge and experience of collaborating partners, private sector networks, information, communication, and technology (ICT) partners, and community-based facilitators.

Box 1: In-Country Partners

Government of Senegal

- Office of the Prime Minister, Unit for Combating Malnutrition (CLM)

- Ministry of Agriculture

- Ministry of Health and Social Action

USAID Projects

- Yaajeende

- Naatal Mbay

- Strengthening Health Systems

Producer Networks

- FEPROMAS

- ADAK

- SYMBIOSE

- APROFES

- UGCPL

- YAKHANAL

Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs)

- Caritas

- ChildFund

- World Vision

- Plan International

Radio Partners

- Niombato FM

- Ndef Leng FM

- Kaffrine FM

- RIP FM

- Alfayda FM

- Koungheul FM

Building Sustainability through Local Partnerships

Working with and through local partners was critical to SPRING’s approach in Senegal. Early in the project, SPRING established formal partnerships with local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and community-based organizations (CBOs) in the agriculture, health, and communications sectors (i.e., producer organizations and farmer cooperatives, women’s groups, and radio stations). These organizations were all well-established in SPRING’s intervention areas and served as implementing partners on the ground for SPRING activities. It was clear from the outset that the Mission’s interest was in SPRING partnering with existing institutions and programs to advance nutrition, not creating parallel structures. SPRING chose to partner with these organizations to encourage local ownership, facilitate the uptake of nutrition-related behaviors, disseminate information to large numbers of people, and improve the likelihood of sustainable results. Our guiding principle was “batir sur l’existant” (building upon what already exists), so SPRING leveraged partners’ existing expertise and the trust they had earned in their communities to successfully introduce nutrition-focused information to community members.

SPRING used a variety of capacity building and SBCC approaches to drive organizational change through structured coordination, sensitization, and training to raise the nutrition awareness of partner organizations and their members and clients. To accelerate the adoption of essential nutrition and hygiene actions and the promotion of good nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices, we worked with collaborating partners to identify and focus on a set of practices and behaviors that were relevant both to partners’ program approaches and to local conditions and needs. In addition to direct capacity building, we employed a range of SBCC mechanisms (e.g., mass media, community video, nutrition messages and display of products at local agriculture and health fairs, etc.) to reinforce work with collaborators and reach a broader audience across the ZOI.

Key to SPRING’s approach in Senegal was to avoid providing direct financial support to partner organizations. Instead, SPRING committed to providing partners with capacity building on nutrition, hygiene, and gender-sensitive best practices which they could incorporate in their work with community members. We subsidized part of the inputs needed to demonstrate nutrition-sensitive agriculture and facilitate access to inputs for individuals by linking demand and supply.

The following section examines SPRING’s major accomplishments through the lens of these categories of partnership.

As fathers and mothers we felt called to act to change this situation and if partnering with SPRING could help then doing so must be a good thing.

-YAKHANAL Staff Member

Activities, Accomplishments, and Lessons

The following section describes the project’s main activities, achievements, and lessons learned, from our experiences as well as those of our partners. All project partners were interviewed at the close of the program to capture these lessons. Their candid feedback was recorded, and key excerpts are shared throughout this report.

Communication Partners

The popularity and evolution of community media in recent years has been heightened with the rapid expansion and reduced costs of information and communication technologies (ICTs). The application of ICTs has opened up new opportunities to exchange information and ideas and engage with the most remote and marginalized populations.

To increase awareness of, and demand for good nutrition-related practices and services, SPRING adopted a multi-faceted community media approach to convey key information through interesting and compelling stories. SPRING worked with local communication and media partners to create informative, engaging, and culturally appropriate content on nutrition-related practices, and disseminate this information to communities within our intervention areas. Working with these partners, SPRING developed and disseminated high quality locally contextualized content which took the form of radio spots and programs, community videos and information, and print materials (e.g., posters, handouts, etc.). By leveraging and maintaining the integrity of local experiences and narratives, while using innovative dissemination channels to reach large numbers of individuals, we sought to motivate and empower communities to improve their nutrition and health.

Radio

As in many parts of Africa, radio is a major source of information for communities in Senegal, and community radio is considered a powerful development tool through which to influence, educate, and mobilize a broad range of audiences. To capitalize on this platform, SPRING partnered with six local radio stations to produce and air fifteen 60-second spots on high-impact nutrition and hygiene practices. The radio stations—Niombato FM, Ndef Leng FM, Kaffrine FM, RIP FM, Alfayda FM, and Koungheul FM—broadcast from Nioro, Foundiougne, Koungheul, Kaffrine, Fatick, and Kaolack, with a reach that covered SPRING’s entire intervention area. Program messages focused on the key areas of nutrition-sensitive agriculture, hygiene, nutrition, and gender.

I really appreciated how SPRING’s team was constantly in the field, close to the community members. All the contextualized messages in the spots and programs were the fruit of things that SPRING’s staff had learned from their experience interacting with the communities in the field. The things that they learned informed the messages that were broadcast. The SPRING team didn’t just stay in their offices but went to the field and understood the target. This was great and not many projects we have worked like this.

-Radio Partner

Some radio spots took the form of jingles, while others had voice-overs delivering succinct messages on topics ranging from the importance of handwashing to the importance of consuming a micro-nutrient rich diet. To maximize saturation, radio spots were broadcast seven days per week, up to 10 times per day, over nine months.

Box 2: Radio Messages Resonate with Listeners

To better understand the impact and reach of our approach, SPRING interviewed 95 randomly sampled men and women between ages 18 and 65 years who lived in villages reached by our radio partners (65 women and 30 men). Radio listeners reported learning about hygiene, the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding, the importance of complementary foods for children ages 6 to 24 months, and the link between gender and nutrition from our radio programs.

Of the interviewees, 78 percent could state the critical moments for handwashing, the benefits of a tippy tap handwashing device, and the importance of keeping the bathroom clean. Further, 71 percent reported learning the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding from the radio programs.

A mother from Koungheul department said: “My five-year old girl repeats this radio spot to me, ‘ayo nene’ (part of a jingle meaning “all day long”), and that’s what attracted my attention to this message. Now, I understand that everything a child needs in their first six months is contained in breastmilk and that exclusive breastfeeding protects against diseases.”

SPRING and radio partners also worked together to create 30 radio programs. These were produced using a talk show format and aired twice a week. Community voices were central to these programs. The invited guests who provided nutrition-related messages during the talk show were influential community members, local government unit health workers, and representatives from agricultural partner networks. The radio animator served as the talk show host and was coached by SPRING staff prior to each interview. The themes for the radio programs were selected to complement and reinforce other SPRING SBCC interventions to further reinforce the messages being shared at community mobilization events, in print, or via community video.

Some of the themes covered during radio programs included ‘the role of men in reducing women’s workload in the household’, and ‘vegetable gardening to improve nutrition and household income.’ While some radio programs were pre-recorded and aired at a later time, others were aired live and listeners were encouraged to call in to ask questions. These programs were extremely popular as they allowed for direct dialogue with community members in real time.

Extrapolating from population distribution data, radio station reach, and data on radio listenership in the region, SPRING reached approximately 918,310 people through these radio spots and programs.

Through community radio, SPRING also rapidly and effectively disseminated key nutrition messages to a large proportion of the population at a relatively low cost. These messages served to reinforce our SBCC work during community video and community mobilization events, saturating the intervention areas with the same target messages.

In addition, through our partnership approach, which focused on building the capacity of radio and programming staff by strengthening their knowledge in nutrition, we fostered a shared commitment to imparting this knowledge for the benefit of their communities. As a result, even as SPRING came to a close, radio stations all pledged to continue airing the nutrition spots and programs, and some even expressed plans to continue to host talk shows on the key nutrition-related themes that SPRING promoted.

We did not limit ourselves to what was found in the contract. For instance, if the contract said we are to play a spot 10 times a day, we would sometimes decide to play the spot even more times than that because we understand the importance of the message and our responsibility to our communities.

-Radio Partner

What We Learned

Community engagement, capacity building, and contextualization: Ensuring relatability of messaging is critical for the adoption of new behaviors or practices. SPRING achieved success using an inclusive process with community members, radio staff, and SPRING staff all contributing ideas and providing feedback to improve the content of the radio spots and programs that were developed. Both radio staff and community members remarked that they enjoyed the spots and programs because of how well they were reflective of the specific needs and contexts of the local communities. Live broadcasts were particularly popular, and radio partners recommended that future projects seeking to share messages should consider focusing at least as much on live shows as pre-recorded messages.

Listeners want to interact and ask their questions, and this is a good thing. The few times there were live broadcasts, there were very lively discussions. When people call in, people understand better. It is good to have live programs with an expert answering questions from callers during a live broadcast.

-Radio Partner

The community-based listening groups SPRING established to monitor the broadcasts and verify that communities understood and adopted the messages revealed that stations consistently broadcast spots and programs more frequently than what was contractually required. Radio staff explained that they were committed to contributing to their communities, and having received training from SPRING on these nutrition-related topics, they were happy to take it upon themselves to capitalize on their platform to further spread these life-saving and well-being promoting messages. Taking the time to build the capacity of radio staff—viewing them as partners rather than contracted agents—fostered greater engagement and encouraged them to play a larger role than expected in affecting change within their communities.

Community Video

As part of our work to promote the uptake of positive nutrition behaviors, we introduced a community video approach in Senegal that had previously shown some success when tested by SPRING in India, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Guinea.

SPRING’s “Community Video for Nutrition” approach involves the community during the design, production, and dissemination stages to create contextualized videos that promote a variety of multi-sectoral nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive behaviors. Our formative research identified practices as well as emotional drivers relevant to target communities to ensure messages would resonate with community members. Video development then drew on these key drivers (i.e., status in the community, recognition by community members, self-fulfillment, and achievement) to incentivize change in both behavior and beliefs. The videos promoted optimal nutrition and hygiene practices while also addressing underlying gender considerations, such as portraying couples’ communication around use of household resources to achieve better nutrition for all family members.

SPRING facilitated the creation of community-based video production teams (or “hubs”) composed of members of partner organizations that showed interest and skills in developing video production. In partnership with Digital Green, we trained these video production hubs how to shoot and edit videos, with sessions on pre- production (creating storyboards and scripts); production (filming and working with actors); and post-production (editing and subtitling). These teams scripted videos based on findings from formative research conducted earlier in the project that helped identify barriers and facilitators to behavior change. They also completed concept testing, which involved working with groups of community members to solicit ideas for videos, choose preferred storylines, and tailor information based on the target community’s experience and reality.

Box 3: The Added Value of Community Videos

Through storytelling, people pass on important knowledge by evoking imagery and triggering emotions, sentiments, and physical responses that make the narrative resonate with an audience. To explore and evaluate the role and effectiveness of community video to share stories that are both interesting and compelling, while also conveying appropriate health and nutrition information, SPRING conducted a study to examine the uptake of key behaviors in villages where community videos were disseminated (compared to neighboring villages that had benefited from SPRING’s radio messaging only).

Study outcomes included dietary diversity of children ages 6-23 months and handwashing practices. Villages exposed to the videos showed a dramatic increase in minimum acceptable diet (MAD) in these children, from 36 percent to 64 percent. Handwashing results were more nuanced, with the percentage of women who knew at least one critical moment for handwashing declining in the comparison villages (80 percent to 69 percent) and remaining the same in intervention villages (83 percent and 81 percent).

As a whole, the survey results demonstrated the effectiveness of community video in improving or sustaining desired nutrition- and hygiene-related practices in Senegal. The full findings from this study can be found in The Value Add of Community Video: Evidence from a Comparative Study in Senegal forthcoming on the SPRING website here.

To further ensure buy-in from local villages, a key aspect of SPRING’s approach was to identify respected members of the community to be featured in starring roles. These community members were known to practice the nutrition-related behaviors being promoted and were eager to model these behaviors. Engaging local villagers as the “star actors” in these films built trust and made the content more relatable and captivating, to support the uptake of promoted behaviors.

SPRING trained local women and men from community-based partner organizations working in agriculture, horticulture, animal husbandry, agro-processing, and health to disseminate the community videos during community gatherings and women’s group meetings. SPRING trained these mediators how to facilitate conversations about nutrition in their communities. They used handheld battery-operated mini-(pico) projectors to show the videos during community events and women’s group meetings, and led group discussions on the topics highlighted in the videos to ensure the audience understood key messages and could share concerns, ask questions, and discuss how they could potentially adapt the suggested practices within their households. In addition, facilitators conducted home visits after video disseminations, helping to reinforce behavior change and providing an opportunity to collect program monitoring data on behavior adoption.

SPRING ultimately created 10 community videos that were disseminated throughout 104 villages. Video topics ranged from the importance of maintaining household hygiene, to the advantages of growing and eating orange-fleshed sweet potatoes (OFSP), to proper storage and preservation of cereal crops. To better understand how these community videos influenced knowledge and practices, SPRING carried out a survey with a sample of approximately 500 women with children between the ages of 6 months and three years at baseline and endline. Both surveys were conducted in 30 villages in the departments of Nioro du Rip and Ida Mouride. Twenty of the villages received the full package of SPRING interventions, including community video dissemination, while the remaining ten villages did not receive the community video intervention (but benefited from hearing SPRING messages through radio and print). Findings from the comparison group showed that the use of community video improved uptake of key behaviors, including consumption of a minimum acceptable diet (MAD) and handwashing (see Box 3).

To help ensure the sustainability of our community video approach, SPRING also trained nine members of the three video production teams on business planning, accounting, and grant writing so that their video production skills could be used as part of broader enterprise activities. These hub members later met with a Dakar-based TV station and communications agency that expressed an interest in the idea of them working as field correspondents. In addition, other USAID-financed projects, including GOLD, Lecture Pour Tous, and Cultivating Nutrition, have expressed an interest in working with our video production hubs.

What We Learned

Our experiences have shown that community media is an exciting, feasible, and effective SBCC approach for nutrition programs. When implemented thoughtfully and based on formative research—ensuring that the intervention engages the community, is suited to the local context, focuses on local capacity building, and is designed with sustainability in mind—community media has the power to change social norms and behaviors. Using video as a communication channel showcased positive role modeling of recommended behaviors to help stimulate behavior change. This innovative storytelling model facilitated communication among peers at the village level, and addressed multi-sectoral factors (nutrition, health, hygiene, and gender) in a single presentation.

Community engagement, capacity building, and contextualization: Community participation and context-specific content are cornerstones of community media. These approaches allow communities to tell their stories and stimulate behavior change through their own perspectives, while ensuring that the information that is given is technically accurate and uniform (compared to traditional interpersonal communication, where messages can be easily left out, misinterpreted, or poorly communicated).

For our community video approach, partners, local authorities, and staff all credited the project’s success to the fact that community videos were contextualized and used community leaders as stars. Community participation and ownership as a principle of community media helps ensure that the content is appropriate and the behavior or practice being promoted is feasible. The actors chosen to act in the videos were well respected members in their villages. Seeing neighbors and familiar faces delivering messages about nutrition promoted trust in the information being shared, allowing community members to easily accept the messages and recommendations shared. Community members need to hear and see people like themselves, and identify with the environment and characters to believe that they can experience a similar change or impact in their lives. The element of fun, to grab attention, is also key. Community members loved seeing their fellow villagers on screen and explained that videos created “with actors from the big cities or from other countries would not have had the same impact.”

Having built the capacity of project partners to develop and disseminate community videos, they are now poised to expand to additional villages, continue to disseminate existing videos, and produce new content as needed, in collaboration with the video production hubs. In sum, community engagement, capacity building, and contextualization are all key to ensure sustainability.

One of the things I find the most successful was the community video. It shows that people need to see a behavior practiced to believe it. The videos were so useful that we have committed to continue dissemination them in different communities even after the project ends.

-YAKHANAL Staff Member

Expanding viewership platform to meet generated interest: The use of video sparked far greater interest and curiosity than more traditional SBCC materials, such as counseling cards alone. The combination of video as a novel communication channel, as well as getting community members involved in video production, drew community members to attend screenings. We had not anticipated such attention and excitement, and only planned to disseminate the videos among the SPRING target audience (PLW and women with CU2). After watching the videos with groups of women, these women insisted that their husbands and other men in the family should view these videos as well, in order to have full family buy-in for a behavior change. To capitalize on this platform, that generated such community interest in the promoted behaviors, some disseminators improvised and screened certain videos to the broader population, but this was done in an ad hoc manner. Future programs considering the use of community video may want to plan for these broader disseminations (at schools, or ‘movie nights’ in the village center) to bring other household members (men, mothers-in-law, and children) into these conversations and create a shared commitment towards adopting new behaviors and practices.

Scalability of approach: The increasing use of portable, digital tools provides an opportunity to expand reach and share information in a standardized way while also encouraging feedback, dialogue, and interaction, even in remote communities. However, community media is typically distinguished by its hyper-local content, commonly defined by the geographic location in which it was produced and for whom it was intended. This is a challenge for scale-up. That said, community media produced in one locality could have an impact on viewers from another region if the content can evoke trust and identification with the participants/actors on screen. Role modeling is an important behavior change concept reflected in community media programs, and when individuals see someone of similar means successfully try something new, they feel like they too can adopt the new behavior. This concept is not as effective when the content is not contextualized and/or when the viewer cannot identify with the person who is role modeling, especially when attempting to change behaviors strongly related to cultural and social norms, as are many health and nutrition behaviors.

In considering the scalability of this approach we should remember that videos can be disseminated through a number of formats. We used pico projectors to test this approach at a small scale, given the rapid growth and saturation of the mobile and smart phone markets, even among remote and marginalized populations, the use of mobile phones, or video-sharing websites on social media is pertinent for a more widespread dissemination. While this approach may not promote the same type of discussion as the traditional dissemination model, the communication platform and dialogue channels that social media facilitates between social groups, policymakers, institutions, and individuals can also elevate local voices to reinforce social and behavior change.

Logistical considerations: Working through existing local partners and procurement processes (for pico projectors and associated equipment) are key considerations when developing a community video dissemination strategy. Challenges with partner and resource coordination reveal a strong need for defining roles and responsibilities of all partners early on in the implementation process. For example, SPRING’s traditional community video approach typically includes household visits by trained mentors to reinforce messages from the videos, but it was not clear to partners from the beginning that follow-up visits were needed for the activity, which hampered planning for adequate resources. Given that the household visits were conducted by unpaid volunteers, these visits were not conducted as systematically as intended. SPRING capitalized on this challenge, though, and designed a comparative study to assess the difference in message retention and behavior uptake between individuals who received follow-up household visits, and those who did not. This could help determine the extent of the value-added of household visits. Findings from our endline survey showed strong recall of the messages from the videos, as well as uptake of the key behaviors promoted whether or not participants received a follow-up household visit which is particularly encouraging when considering the scale-up of community video, since home visits can be resource intensive.

Video development was also a longer process than expected, taking time away from other activities. Community video production is typically a fairly rapid process. Shooting a video usually takes two days (one day of preparation and one day of shooting), and editing adds an additional day. However, production required more direct support in Senegal, partially due to a large number of stakeholders, different levels of baseline knowledge, literacy levels of volunteers, and experience/capacity of local staff and partners. When working with stakeholders from many sectors, it may be necessary to build additional technical capacity in health, agriculture, and other domains, in addition to video production training. It proved initially challenging to find a balance between supporting production teams and allowing them to work autonomously to ultimately enhance the sustainability of the approach and allow it to be more community led.

Before the trainings we didn’t understand the link between nutrition and agricultural practices. We asked ourselves, how we would be able to solve the problems of nutrition through changing our agricultural practices. Now we understand clearly the gateways to improved nutrition.

-YAKHANAL Staff Member

Box 4: Nutrition-sensitive agriculture addresses the underlying causes of malnutrition by—

1) improving food production, availability, nutrient density, quality, and diversity of the food a household consumes;

2) providing agricultural income for food and non-food expenditures, such as health services; and

3) empowering women, which can promote household spending on food and health care as well as save women’s time and increase their capacity to care for themselves and their young children.

Agricultural Partners

Agricultural partners were an important part of SPRING’s work to help facilitate access to key inputs, information, and services for nutrition, specifically the improved production, trade, and consumption of highly nutritious foods that contain vitamin A, zinc, iodine, and iron. Specifically, SPRING sought to make agriculture more nutrition-sensitive by supporting agriculture partners to identify, prioritize, and promote nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices. Using a multi-sectoral approach and the conceptual pathways framework, SPRING identified several key nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices within the context of each partner network (see Box 4). We then promoted those nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices through our SBCC approaches and encouraged our producer networks to adopt them.

SPRING partnered with six local producer networks promoting cereal value chains (millet and maize), horticulture, and poultry farming within our intervention zones. We also formalized our collaboration through memoranda of understanding (MOUs), as SPRING did not provide financial incentives to the partners. These producer networks were our primary point of entry to introduce nutrition-sensitive and nutrition-specific practices. The MOUs laid out how we would collaborate, described the value added to both parties, with SPRING agreeing to provide training and capacity building to partner members, and partner organizations committing time and agricultural inputs. For example, if the partner was willing to provide the human power and initial resources (i.e., land and seeds) to cultivate a new crop, we would provide training on how to grow, store, and market it.

To establish a common framework with our partners, SPRING provided a comprehensive training on nutrition-sensitive agriculture and included modules on the different pathways to link nutrition to agriculture, the seasonal calendar and its effects on nutrition, and different nutrition-sensitive agricultural practices (NSAP) that networks could choose to promote within their communities. Training sessions with farmer networks enabled us to analyze practices in the different stages of value chains, and identify NSAP (and messages) that could be prioritized, based on the context of each network and the relevant value chain. The practices and nutrition-sensitive messages were then disseminated through community video, radio, field demonstrations, exchange visits, and community mobilization events.

SPRING allowed us to have a perspective on nutrition and health that we didn’t have before. Before we were only focused on production and now in addition production we want to make sure the crops we cultivate are very nutritious. We wouldn’t have this perspective without SPRING.

-FEPROMAS Staff Member

The table below shows SPRING partner networks, their areas of intervention, and the value chains of focus.

Table 2: Networks, Value Chains, and Zones of Intervention

| Network | Value Chain | Department | Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fédération des Producteurs de Maïs du Saloum (FEPROMAS) | Obatampa maize, horticulture, poultry farming, OFSP | Nioro du Rip | Kaolack |

| Association Pour la Promotion de la Femme Sénégalaise (APROFES) | Horticulture, poultry farming, OFSP | Kaolack, Foundiougne | Kaolack and Fatick |

| Union des Groupements de Producteurs de Céréales Locales (UGPCL) | Bio-fortified millet, horticulture, poultry farming, OSFP | Kaolack | Kaolack |

| Association pour le Développement de l’Agriculture à Kaolack et Kaffrine (ADAK) | Millet, horticulture, OFSP | Koungheul | Kaffrine |

| Association pour le Développement de l’Agriculture à Kaolack et Kaffrine (ADAK) | Bio-fortified millet, horticulture, poultry farming, OSFP | Nioro du Rip | Kaolack |

| YAKHANAL | Maize, horticulture, poultry farming, OFSP | Foundiougne | Fatick |

The nutrition-sensitive agricultural practices promoted by SPRING aimed to diversify food production, increase agricultural income, and increase women’s empowerment, in alignment with the Conceptual Pathways between Nutrition and Agriculture framework.

Diversifying Food Production for Consumption and Income

To diversify food production for improved dietary diversity and increased income, SPRING sought to strengthen coverage and capacity of input suppliers and service providers to support nutrition-sensitive agricultural production and practices. Orienting our crop selection toward addressing priority health concerns, promoting indigenous foods, encouraging dietary diversity, and generating revenue, as well as building on Yaajeende’s (our partner and another USAID project), success with its nutrition-sensitive interventions, SPRING worked with partner networks to promote more nutritious variants of common crops such as bio-fortified millet (which is rich in iron and zinc), Obatampa maize (protein-rich) and OFSP (which is high in vitamin A).

We began the project with only 2 hectares of Obatampa maize and today we have over 200 hectares. We didn’t know much about orange-fleshed sweet potato (OFSP) at the beginning and we began with only 2 plots (parcelles) now we have 47.

-YAKHANAL Staff Member

SPRING established demonstration plots and organized field exchanges to promote NSAP and share best practices with network members on growing, harvesting, storing, and marketing the crops, as well as fruit and vegetables in micro-gardens outside their compounds, or in shared community gardens. We demonstrated how to create a micro-garden featuring peppers, chili-pepper seeds, tomato, squash, carrots, onions, cowpea, cabbage, hibiscus, okra, OFSP vines, banana saplings, moringa, and papaya. In all departments, we installed model micro-gardens (complete with tippy-tap handwashing stations) and trained 240 women and 25 field agents, who in turn trained and supported approximately 2,700 women in installing micro-gardens in 90 villages.

The cereal processing machines have been beneficial for the community members because they reduce women’s workload and also increase their revenue.

-ADAK Staff Member

SPRING provided technical assistance to its cereal producer partners by teaching post-harvest handling of cereal crops to ensure quality grain and minimize losses through optimal storage techniques. We also introduced, through demonstration sessions, systems of mechanized threshing of cereals using locally developed and inexpensive technology. This threshing system reduces women’s workload by accomplishing in hours what would otherwise constitute a week’s work.

Box 5: Agriculture Partnership Accomplishments in Numbers

- 96 network members trained in agricultural conservation techniques

- 9 exchange visits conducted for a total of 354 participants, including 214 women

In the project's last quarter alone:

- 600 kg of Obatampa maize seed and 150 kg of bio-fortified millet seed distributed

- 5.6 tons of Obatampa maize seeds sold by one agriculture partner network (enough for 280 hectares) to member producers

- Another partner sold 300 kg of biofortified millet seed to the PAFA project

- 366 bags of OFSP—i.e., 183,000 vines—accessed by agricultural partner networks for a planting of 60 demonstration plots of 1,000 m² each.

It is important to remember that farmer networks used their own funds to procure all seeds, OFSP vines, and fertilizers used for these demonstration plots, which demonstrated their commitment to the collaboration with SPRING and to promoting good nutrition practices and nutrition-sensitive agriculture. SPRING, in turn, offered animal-drawn rippers for conservation agriculture to the farmer networks promoting the bio-fortified cereals.

Improved village poultry production was also promoted to partner networks to encourage the consumption of protein-rich chickens and eggs. SPRING trained partner cooperative members how to construct chicken coops, and how best to feed, vaccinate, and breed chickens. We also donated two Holland Blue roosters, selected for their genetic characteristics which allow them to grow fast, large, and produce a lot of eggs, along with twenty local hens, starter feed, and vaccinations to each of the six agricultural partner networks. In turn, the networks pooled resources from members to pay for the construction of the chicken coops and the upkeep of the chickens.

To generate enthusiasm around consuming these new foods, SPRING also developed and disseminated a series of recipe cards featuring OFSP, bio-fortified millet, Obatampa maize, as well as the fruit, vegetables, and poultry promoted. These cards explained the nutritional benefits of each key crop and provided recipes on how to prepare dishes using them. Additionally, we produced community videos that promoted cultivation, processing and storage of these new products and showed different uses of these foods in household meal preparation for improved nutrition.

SPRING also trained partner networks how to sell a portion of the crops and vegetables cultivated as well as some of the eggs hatched from village poultry to generate additional income. With increased access to agricultural inputs, we created a network of community-based service providers (CBSP) by contacting reliable vendors of quality products at the national level, and identifying CBSPs from within the membership of our six producer partners. We trained the CBSPs in key service areas including land preparation, crop spraying, irrigation services, grafting, and livestock vaccination, and facilitated meetings between vendors and CBSPs with the objective of facilitating the sale of inputs (i.e., fertilizers, improved seeds, tools, iodized salts, and enriched flours) and creating a circuit of demand and supply. The system is functioning well, and by the time SPRING ended, vendors had already supplied and resupplied CBSPs.

Micro-gardens are brilliant because they are simple and they do not require that much work but they allow you to increase your family income and have nutritious foods. [You are] able to watch over your little plot because it is within your compound and you don’t have to worry about it getting accidentally destroyed or eaten by animals.

-YAKHANAL Staff Member

Now other cooperatives are asking us for seeds and inputs and we are in a position to give them advice. We tell them about what we have learned from SPRING. This is very good for us.

-ADAK Staff Member

What We Learned

SPRING explored how to address the underlying causes of malnutrition through nutrition-sensitive agriculture by training local agriculture agents in tailoring nutrition sensitive agriculture approaches to their local contacts. Across our activities and partnerships, we found that successful cross-sectoral training is key for developing the collaboration that nutrition-sensitive activities require. Understanding how and why to make agriculture practices nutrition-sensitive can be challenging. However, once practitioners understood why they should care about nutrition, and realized the opportunities they held to make a difference within their communities—to improve household diets and the overall well-being of their families—we found that engagement and buy-in was intrinsic, and didn’t require financial incentives to spark motivation to participate in proposed activities. The incorporation of nutrition-sensitive agriculture approaches into the training of agriculture extension agents was embraced by every one of SPRING’s agriculture partners who saw value in considering nutrition in their work.

A lot of our members did not mind paying out of pocket because they were inspired by SPRING. They looked at all that SPRING had been able to do for the community and they saw that even though SPRING wasn’t paying them salaries or per diems, they were nevertheless heavily investing in the community so we don’t mind sacrificing a little as part of our own contribution.

-YAKHANAL Staff Member

Introducing new techniques and learning by doing: The approach of creating demonstration sites to introduce NSAP and further sharing best practices through exchange visits received a lot of positive feedback from partners and was documented by local radio stations. Demonstration plots—reinforced with exchange visits, radio coverage, and community video—galvanized a lot of enthusiasm, and early adopters of improved NSAP were rapidly identified among the members of partner organizations to further champion promoted initiatives. This is particularly encouraging because SPRING did not pay for the required inputs in the first year. Instead our partner’s commitment was evidenced by their willingness to purchase all required inputs for demonstration plots (seeds, cuttings, fertilizers); while SPRING only provided technical assistance and the transport for these items.

The cascade model used for propagating the use of micro-gardens was also particularly successful. SPRING installed a total of 90 model micro-gardens complete with tippy-tap handwashing stations. In each area covered by one of our partner organizations, we targeted 15 villages, thus reaching 90 villages across all departments within our area of intervention. Each demonstration was attended by about 30 women and at least 4 field agents who committed to replicating the micro-garden demonstrations in 14 other villages. In each of these villages, women received seeds and saplings to install a micro-garden and tippy-tap in their own backyards. By the end of the program, a total of about 2,700 micro-gardens were created from this investment.

The tippy taps were also brilliant because we had so many cans and bottles lying around that we had no use for but we now use them to install tippy taps and wash our hands at key moments of the day.

-YAKHANAL Staff Member

We ran into challenges with promoting improved poultry practices. Soon after introducing the ‘improved’ chickens, an outbreak of an epizootic disease occurred, resulting in the deaths of entire coops of chickens. To help protect participants’ chickens from disease in the future, we strengthened the capacities of CBSPs in veterinary services by putting them in contact with a veterinary office. Many beneficiaries who lost chickens remained so committed to trying out the improved poultry rearing approach that they pooled their funds to buy replacement roosters and hens. In one village, Sénala Keur Abdou, the group opted to replace the chickens with turkeys, as they are less prone to disease.

Box 6: Shifting Social Perceptions with Gender Champions

In Wolof, the term gooru mbotay means “a man who accompanies women,” or a man who assists his wife. Prior to introducing the Gender Champion Approach, this term was considered derogatory in the target communities. Indeed, a major obstacle to greater uptake of good gender practices were existing social norms. While many men expressed a desire to help their wives with domestic tasks, they worried about their neighbors’ opinion of them, since Senegalese society associates household tasks with women. This perception changed considerably by SPRING’s use of the Gender Champion Approach. After champion couples were trained and elevated as role models, via community events, radio and video, the champions affirmed that being called “gooru mbotay” was now a source of pride.

As Arame Wilane, wife of one of our champions from Koungheul summarized: “Before, there were some men who helped their wives with household tasks, but they did it in secret because they didn’t want the neighbors or their family members to see them. But ever since people started hearing about champions, these men don’t feel embarrassed when they go fetch water or wood, or help clean the house. Plus, even those who didn’t used to do these things have started imitating the champions. It’s really a wonderful thing, especially for us women.

Increasing Women’s Empowerment

Women play an essential role in family nutrition, and research shows that income controlled by women is more likely to be spent on food and health care for the family (UNICEF 2011; Smith et al. 2003). Pursuing women’s empowerment involves increasing women’s decision-making ability related to household income, as well as freeing up women’s time and energy to focus on family nutrition, child and infant care, and self-care. Since in many cases women’s time is spent on taxing household chores, this is not often possible. With this knowledge, SPRING worked with partner networks to pursue women’s empowerment within our target areas of intervention by 1) increasing their potential income (for food and non-food expenditures), 2) identifying solutions to improve efficiency and reduce their energy expenditure, and 3) improving their knowledge and awareness of how to care for themselves and their families from a nutrition standpoint.

Each of the partner networks we collaborated with included a women’s group. SPRING prioritized partnership with women’s groups to ensure that women were the primary beneficiaries of the agricultural activities we supported. SPRING’s activities with micro-gardens and improved poultry-raising, for example, were all carried out by the female members of our partner networks. SPRING also purchased and donated 12 multi-function cereal processors and distributed two to the women’s groups of each agricultural partner network. The 3-in-1 machines husked, ground, and crushed cereals such as maize and millet. These tasks are traditionally completed by women who spend hours at a time using a mortar and pestle. Providing the women’s groups with this machinery aimed to reduce women’s post-harvest workload, increasing the time, energy, and money they have to devote to good maternal and child nutrition. In addition to training these women’s groups how to operate, clean, and maintain the machines, SPRING provided training on the business-related aspects of selling processed cereal and renting out the machines to help generate additional income.

In the past we had difficulty getting inputs, especially bio-inputs. Through SPRING we were able to get access to bio-fortified millet. We also learned a lot about OFSP. We had other vegetables but this was new to us. For the cereal processing machines, it has really had an impact in terms of reducing workload and increasing income. So, our partnership with SPRING has really born fruit.

-APROFES Staff Member

“One thing I am very proud of is that because of this partnership with SPRING our network was able to produce so much Obatampa maize that we were able to donate 200kg of it to ChildFund so that they could use it to help malnourished children. We’ve done a similar thing with the enriched flour that our women’s groups have been able to produce with the help of the cereal processing machines that SPRING donated. We sell this enriched flour at a very low price to community health agents who use it to help feed malnourished children in the community.

-YAKHANAL Staff Member

As part of SPRING’s SBCC strategy, we piloted the Gender Champion Approach (see Box 6), which aimed to transform sociocultural beliefs around gender roles and increase male-female partnership and distribution of workloads within the household to improve family health and nutrition outcomes. We did this by encouraging women’s participation in household financial and nutrition-related decision making, as well as men’s involvement in care, nutrition and hygiene-related tasks to reduce women’s heavy workloads. The Gender Champion Approach identified men who were already well known in their communities for performing desired gender-equitable practices, and equipped them with knowledge and tools to become advocates for gender equality. These men and their wives became outspoken advocates for gender equality in their communities, speaking to community members about the importance of shared chores, and dispelling cultural taboos about traditional gender roles in society. Champions were publicly recognized during our community mobilization events, and a video starring several gender champions was disseminated across target villages. The champions spoke to audiences about their behaviors and the positive effects they were experiencing, especially better health, higher income (due to women having more time to pursue income-generating activities), and greater peace in the household. As champion couples became recognized as leaders, they began to influence others to follow their example.

What We Learned

I particularly liked SPRING’s gender champion approach because it addresses ideas that are often taboo in communities. For instance a man fetching water for his wife is taboo. But these actions were promoted and celebrated in such a participatory way that it was not taboo and now many men assist their wives by fetching water for them.

-YAKHANAL Staff Member

Gender sensitization: Empowering women improves nutrition for women, their children, and other household members. The pathway from women's empowerment to improved nutrition is influenced by many factors, including social norms, knowledge, skills, and how decision-making power is shared within households. In Senegal, we sought to support women’s empowerment by tackling each of these factors in unison to ensure they mutually reinforced one another. It was imperative, for example, to train male and female partners on gender equity, and sensitize communities to challenge social norms on gender roles, prior to favoring women’s networks for interventions (e.g., homestead garden and poultry rearing promotion, or the distribution of the cereal transformation units). Galvanizing support from all parties and avoiding unintended negative consequences, such as jealousy towards beneficiaries, or creating additional work and labor for women without task alleviation elsewhere, was critical.

Sparking dialogue: Topics surrounding gender roles and cultural norms are often difficult to discuss and even more difficult to change. The project’s various community media interventions also served as conversation starters between couples, to encourage men to help with child care beyond providing financial support, and to lead couples to adopt the positive behaviors viewed in the videos. Gender issues and deeply entrenched cultural norms could be portrayed in a safe community setting to open a discussion with community members, enabling them to share experiences through stories.

Celebrating role models: Our Gender Champion Approach showed how small actions by one individual can influence the actions of others within a group, holding the potential to influence further individuals, and eventually affecting the entire community. Transforming a community’s perception of an individual or a couple from outliers to champions, whose behavior is worthy of replicating, takes time and requires that they have the appropriate tools to be effective. The combination of 1) training champions to effectively advocate for gender equity and model desired behaviors with 2) public recognition for communities to witness these key influencers being lauded as ‘champions’ was well received and proved to be an effective strategy. Community members were receptive to discussions of gender roles and the possibility of challenging traditional norms, indicating that the time may be ripe to consider scaling the Gender Champion Approach.

SPRING provides the following recommendations for any program considering these activities:

- SPRING did not just consider gender a cross-cutting theme. We made gender a priority and deliberately planned and budgeted for gender-focused activities, capacity building of local organizations and communication around gender to ensure this was given the attention needed.

- SPRING developed a gender training manual (which was subsequently adapted for use in Ghana and Guinea) that can be re-purposed for any future training. While we provided a one-day training to champions and partner staff, we recommend this be extended to two days, to allow participants more time to reflect on concepts and tools.

- Seizing every opportunity for public recognition was critical, and developing a community video featuring champion couples as stars proved to be a great catalyst for discussion and behavior change. The power of film to turn people into ‘stars’ that others seek to emulate is quite remarkable, as evidenced through the impact of all of the SPRING community videos.

- Leveraging the position of community-based organizations, local NGOs, and farmer/producer networks to promote a Gender Champion Approach, and conducting follow-up visits and refresher trainings to allow champion couples additional contact with program staff and one another to share successes and receive support to overcome identified obstacles, is also critical. Leveraging the capacity of local institutions in this way would improve effectiveness and efficiency, and help ensure the sustainability of the intervention.

Health Partners

SPRING also sought to partner with stakeholders from the health sector. While we initially planned for Programme de Santé-Santé Communautaire (PSSC2) and Renforcements de prestations de services (RPS) to be our primary nutrition/health collaborative partners, these two USAID-funded programs began to prepare for closeout shortly after the launch of SPRING, leaving an awkward transition period before the next generation of health projects was to commence. To keep our objectives moving forward, we identified government health networks (i.e., health workers at local health posts and clinics) that worked with PSSC2’s partners within the health districts in our intervention zones, with the intent to train them on nutrition-related best practices to share with community members.

I have learned so much from working with SPRING. The SPRING approach of working through partners is very much like the CLM’s approach since we also work through several different partners. I call CLM’s approach “doing by doing” [faire faire], as we do not directly do activities, but we work through implementing agencies.

-CLM Staff Member

Box 7: Hygiene Monitoring Units (HMUs): A Local Approach to Improving Hygiene

One of the innovative ways SPRING sought to increase awareness of good hygiene practices and influence the behavior of community members regarding personal and household hygiene was by supporting the creation of hygiene monitoring units (HMUs) that regularly monitor hygiene practices within their communities.

These groups, also known as “Dynaset-setal” groups (a Wolof phrase meaning “I commit to a clean environment”) consisted of 6-10 highly engaged and influential community members, often community health workers, village heads, local government unit representatives, and Koranic schools.

SPRING conducted workshops for HMU members, providing instruction on the critical moments of handwashing, the different steps to properly wash hands, and the benefits of using a tippy-tap. The members conducted household visits around their communities to inspect households and assess how many had functional tippy-taps and/or drying racks, track the number of people aware of at least three critical moments of handwashing with soap, and provide support to households that had questions or were not following all guidelines.

However, because of a change to the per diem policy applied by USAID Senegal, certain syndicates of health workers were unable to collaborate with SPRING. Despite consultations with the district and regional medical officers, no solution was identified to address this problem other than to target and work through health actors that were not affiliated with the Ministry of Health. SPRING therefore adjusted plans and leveraged an unexpected yet fruitful relationship with the Cellule de Lutte Contre la Malnutrition (CLM). The CLM is attached to the Prime Minister’s Office and is charged with articulating and coordinating a multi-sectoral strategy to reduce malnutrition in Senegal. One of the CLM’s projects, the Programme de Renforcement de la Nutrition (PRN), was implemented through NGOs referred to as implementing agencies.

Through the relationship with the CLM, SPRING worked with some of the implementing agencies operating within SPRING’s intervention areas, including PLAN, ChildFund, and Association pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF). Community-based staff from these agencies worked in local health huts and provided health information. SPRING organized workshops on maternal infant and young child nutrition as well as hygiene for staff from these implementing agencies. These staff members also attended nutrition-sensitive agriculture trainings organized for agricultural partners, which allowed health workers to incorporate key nutrition-sensitive messages into their daily work in their communities. They informed women who visited the health huts about the importance of exclusive breastfeeding and reminded them to attend their pre-natal and post-natal visits. They actively participated in community mobilization activities, such as weekly markets, and local technology fairs to promote key nutrition, hygiene, and gender messages through activities such as ‘quiz-show’ contests, tippy-tap installation demonstrations, live interactive talk shows, and drama performances. They also conducted home visits to give advice on how to construct tippy-taps and encourage community members to keep their compounds hygienic.

What We Learned

Identifying the right partnerships: Establishing partnerships within the health sector proved to be the most challenging for SPRING, largely due to the fact that SPRING did not provide partners with financial assistance and community health workers are used to some form of compensation from implementing agencies and donors. The unexpected partnership with the CLM opened new doors within the health sector, as the organization helped advocate to community health workers on our behalf. Since CLM is well established and linked with the Senegalese government, it is our hope that the project’s most successful approaches and legacy will live on through the CLM and their partners.

Best Practices, Challenges, and Recommendations

Best Practices

Multi-sectoral approaches and activities: People in communities don't live their lives siloed in health or agriculture sectors but in families and villages, where all the constraints and opportunities of life converge and are intertwined. Acknowledging the range of determinants that affect nutrition, we recognize the need for continued programming and research that focuses on multi-sectoral approaches to improve health outcomes. While multi-sectoral programming can be challenging, our experience has shown that building the capacity of varied partners from different sectors, in order to “connect the dots” and promote optimal nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive behaviors in their programs and the communities they serve, is efficient and effective.

Our community video approach strengthened multi-sectoral programming by encouraging collaboration from partners representing different sectors as well as specialists within the same organization (agronomists, nutritionists and communication specialists). Videos covered topics that naturally intersect in community members’ daily lives (not separated by programming silos), to help viewers easily relate to the content and catalyze behavior changes. We also found that agriculture and health partner staff could share videos about nutrition without having to become nutrition experts themselves. Indeed, community video provides a tool for implementers to develop context-specific and technically accurate content that can be disseminated through various partner-led efforts. Because the community video model can be adapted to a number of platforms and sectors, allowing programs to share nutrition information with or without nutrition experts on staff, it could be integrated readily into partner programs.

Local partnerships to build on what already exists: SPRING demonstrated that much can be accomplished in a short timeframe when working with established local partners. We recognized an opportunity to improve nutrition outcomes by leveraging the reach of existing programs which had extensive reach into communities to strengthen the nutrition sensitivity of the information they provided. By working with and through these partners, who were well trusted by their communities, SPRING was able to quickly mobilize and begin implementing in a relatively short time period.