Executive Summary

SPRING, in collaboration with staff from HKI Sierra Leone, conducted four Barrier Analysis (BA) surveys in fifteen communities across three chiefdoms in Tonkolili District, Sierra Leone to identify behavioral determinants of consuming fish and pumpkin by pregnant women and children 6-23 months old. The BA was intended to inform social and behavior change communication (SBCC) efforts promoting dietary diversity. The BA team used the CORE Group’s Barrier Analysis Facilitator's Guide1 using survey questionnaires to identify differences between Doers (those who engage in the targeted practice) and Non-doers (those who do not) on a set of key behavioral determinants.2

While pumpkin is widely consumed during the rainy season while plentiful, Non-doers reported low consumption during the dry season when it is scarce. Lack of availability, high price, and poor access to preferred quality of pumpkin were reported much more frequently by Non-doers than by Doers. Low perceived action efficacy of feeding a child pumpkin is an important barrier as Doers were 2.7 times more likely than Non-doers to say that giving a child pumpkin to eat prevents malnutrition. Non-doers were 4.7 times more likely to say that feeding a child pumpkin can cause rashes (Perceived negative consequences).

Among pregnant women, Non-doers were more likely than Doers to report eating pumpkin “only when it is plentiful”. Barriers included poor availability, high cost, and the perception that it is difficult to store pumpkins. Doers were 3.2 times more likely to list good taste/texture of pumpkin as an advantage (Positive consequence). Non-doers were more likely to say that pumpkin was not always available in their village during the dry season (p < 0.005). One-third of Doers grew their own pumpkin rather than purchasing it. Non-doers were more likely to purchase whole pumpkins (possibly limiting the frequency of purchase) while many Doers purchase pumpkin in small slices. Doers were 8.5 times more likely to say that health workers approved of pumpkin consumption while pregnant (Perceived social norms) (p < 0.005).

Although fish is widely consumed daily in sauce, the amount consumed per person is low. Low availability and affordability, and limited access to the varieties desired were the biggest barriers to daily and year-round consumption of a beneficial quantity of fish. Another barrier is poor access to safe, quality (smoked/frozen) fish. Fish is sold many days or even weeks old with maggots being seen on occasion. Perceived action efficacy also plays a role as Doers were 4.8 times more likely to say that fish consumption prevents malnutrition in children and 3.9 times more likely to say that it prevents anemia in pregnant women.

These results informed the development of SBCC materials to promote dietary diversity and also speak to the importance of improving access to affordable, good quality fish and pumpkin.

Introduction

The SPRING project and Helen Keller International (HKI) in Sierra Leone embarked on an eight-month learning project in Sierra Leone to investigate how to 1) improve feeding practices of pregnant women and infants and 2) increase household access to nutrient-rich foods for year round diverse diets. The strategic objective of the learning agenda is to improve collaboration, learning, and adaptation related to social and behavior change (SBC) approaches for maternal, infant, and young child nutrition (MIYCN), and nutrition-sensitive agricultural practices. The overarching goal of the effort is to contribute to improving dietary diversity among households with pregnant and lactating women and children 6– 23 months old, specifically in the target area of Tonkolili district, Sierra Leone. The types of foods that can improve dietary diversity in this context are many. In order to provide focus and sufficient depth of analysis the study selected two commodities fish and pumpkin based on nutrients needed during the “first 1,000 days.”

Objectives

The barrier analysis survey aimed to investigate and identify behavioral determinants associated with the consumption of fish and pumpkins using the CORE Group’s Barrier Analysis Facilitator's Guide. In addition, it aimed to capture current issues, including cultural practices, associated with year-round access to and utilization of these two nutrient-rich foods in order to improve dietary diversity of the first 1,000 days among households in select communities.

Methodology

The survey was conducted in 15 selected communities in the three chiefdoms in Tonkolili district: Kafe Simiria, Kholifa Rowalla, and Tane. The survey used purposive sampling to yield a mixture of size and access to roads, markets, and health facilities and was also based partly on ease of access by the survey teams. Three teams of two interviewers and a supervisor each conducted the survey of doers and non-doers with mothers/caregivers of children 6–23 months (referred to as Teams A, B, and C). The remaining team with three interviewers and one supervisor conducted the survey for doers and non-Doers targeting pregnant women (referred to as Team D) within the same communities surveyed by Teams A, B, and C. Mothers/caregivers of children aged 6–23 months old were interviewed regarding feeding both fish and pumpkin to the child and pregnant women were interviewed regarding their own consumption of fish and pumpkin during pregnancy. All teams administered the behavior questionnaire on fish for a total of three days, and then administered the behavior questionnaire on pumpkin for a total of three days. Teams A, B, and C interviewed approximately 5 doers and 5 non-doers of behavior per day who were caregivers/mothers of children ages 6–23 months, for a total of 10 interviews of doers and non-doers a day per team. Approximately 21 pregnant women were interviewed each day by Team D.

All responses were collected as hard copies and double checked by supervisors in the field, and later coded for analysis. Comparison was made for responses provided by “doers” (people that actually "do" the desired behavior according to criteria outlined per questionnaire) versus “non-doers.”

Questionnaire Development

HKI staff in consultation with SPRING technical advisors developed the questionnaires in English for both pregnant women and children from 6–23 months of age for both fish and pumpkin. The survey questionnaires were designed to identify differences between doers and non-doers on a set of key behavioral determinants, as listed in Figure 1.3 Reviews of the questionnaire were conducted prior to and as part of training. The questionnaires were pretested on different groups of respondents to ascertain the flow of the questions, criteria for categorizing doer versus non-doer, and the suitability of a “prompting” word/phrase in Krio, Limba, and/or Themne, the most commonly spoken local languages. On the basis of the pretest results, questionnaires were modified and finalized for data collection prior to the survey. Of note, over the first half day of fieldwork no women were found who did not eat fish every day, so the questionnaire was modified in the field to relax the criteria for a non-doer, allowing the team to classify a woman as a doer or a non-doer according to the quantity of fish consumed.4

Figure 1. Important Determinants That Influence Behavior

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Training of Interviewers

HKI conducted a three-day training for hired interviewers (Figure 1). The nine hired interviewers (three women and six men) were recruited based on their ability to speak Krio and Themne, read and write in English, and their previous work experience on surveys and assessments. Training topics included determinants of behaviour, doer versus non-doer, good interview techniques, and familiarity with the questionnaires (both for pregnant women and for caregivers/mothers of children aged 6–23 months). Interviewers practiced administering the questionnaires first through role play and then pretesting in the field, and provided feedback.

Training included all survey materials, including hard copy of questionnaires. Materials were pretested through simulation exercises and tools were then finalized and printed.

Selection of Households

The first house visited in each community was randomly selected according to the following steps:

- The approximate geographic center of the community was identified.

- A random direction was chosen from the center using the spin-the-pen technique.

- All houses from the center to the edge of the area were counted and assigned a number.

- A random number table was used to select a number (between one and the total houses counted). The house assigned the corresponding number was the first visited.

- The next house to be visited was to the immediate left of the previous house visited.

Selection of Eligible Child and Pregnant Women in the Survey

At each house, all eligible households (those eating from the same cooking pot) were identified and the participants selected randomly as follows:

- The enumerator asked the head of the household or a caregiver how many caregivers/mothers with children between 6–23 months were present in the household.

- The names of all eligible children were recorded on pieces of paper, and someone in the household was asked to draw one piece of paper to select the child.

- If the mother/caregiver of the selected child was available, the enumerator sought consent and proceeded to interview her.

- If the mother/caregiver was not available or not willing to be surveyed, the enumerator recorded it and moved to the next eligible mother/caregiver.

- The enumerator continued according to these steps, moving on to the next house to the left until they had interviewed five caregivers/mothers of children aged 6–23 months per day.

Estimating a Child’s Age

The enumerators confirmed a child’s age by referring to its immunization/yellow card or other written document with the child’s date of birth. When households did not have any reliable document, surveyors were required to estimate age of child using a pre-agreed local calendar of events.

Selection of Pregnant Women at the Health Facility

The nearest health facility for each community was selected for interviewing the pregnant women and continued at households through random selection until the daily quota was met. Pregnant women were randomly selected using the table of random numbers.

Data Cleaning, Entry, and Analyses

All the questionnaires were brought to national level for data verification. Data were entered and coded before analysis. Data was cleaned; double checked against the hard copies, and then analyzed. Statistical significance between doers/non-doers was tested by chi tests at p < 0.05 significance level.

Ethical Clearance

HKI applied to the Office of the Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee at the Ministry of Health and Sanitation for ethical approval to conduct this study. Ethical clearance was granted following a review of the statement of purpose, components of research, design and procedures of research, and curricula vitae of implementation team members. Throughout the study, ethical standards were maintained with all respondents granting consent prior to participation and all data being anonymized.

Results

A total of 96 mothers/caregivers were interviewed for the behavior of fish consumption (49 doers and 47 non-doers) and 101 (48 goers and 51 non-doers) for pumpkin consumption by children 6–23 months old (Table 2). Sixty pregnant women were interviewed on behavior associated with pumpkin consumption (33 doers and 27 non-doers) and 42 for fish consumption (17 doers and 25 non-doers). All the significant differences between doers and non-doers are reported at p < 0.05 unless stated otherwise. A full list of significant responses to questions/prompts will be found in Annexes 1–4.

Table 1. Criteria for Doers versus Non-Doers

| Fish consumption, children, aged 6–23 months | |

|---|---|

| Doer | Non-doer |

| Fish consumption pregnant women | |

| Doer | Non-doer |

| Pumpkin consumption, children aged 6–23 months | |

| Doer | Non-doer |

| Pumpkin consumption, pregnant women | |

| Doer | Non-doer |

| Child fed fish at least 2–3 times a week | Child fed fish once a week or less frequently |

| Pregnant woman with approximately one hand palm of fish per person in her household yesterday (rough estimate from graphic on questionnaire) | Pregnant woman with less than one hand palm of fish per person in her household yesterday (rough estimate from graphic on questionnaire) |

| Child fed pumpkin in past month | Child not fed pumpkin in past month |

| Pregnant woman who has eaten pumpkin in past month | Pregnant woman who has not eaten pumpkin in past month |

Fish Consumption in Children 6–23 Months Old

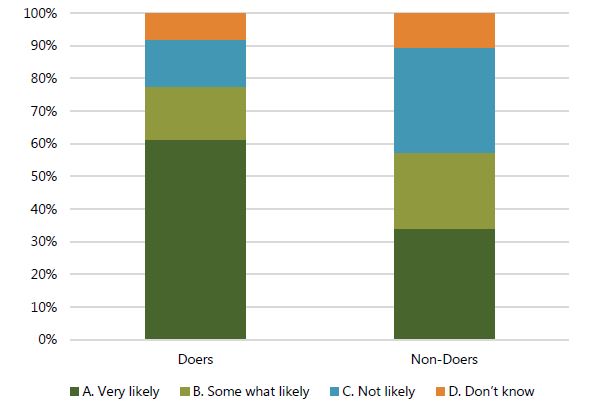

While conducting the surveys, it took much longer to find non-doers than doers, categorizing a doer as having a child fed fish more than once a week, and a non-doer once a week or less frequently. While various factors make it “very difficult” to give children fish every day, the most significant factor was economic barriers, as vocalized by non-doers, including high cost and money problems. The responses from mothers/caregivers highlighted differences of perceived consequences as key determinants. Doers were 4.8 times more likely to include health benefits as an advantage of fish consumption for their children than non-doers: “Child grow strong /smart/faster rate/ good baby/fit/healthy/active/grows well /fresh/good looking /weight.” Doers were also 3.9 times more likely to vocalize an advantage of fish to be “prevent sickness anemia/ diarrhea/malnutrition” than non-doers. As illustrated in Figure 3, just over one-third of non-doers believe fish is critical to preventing malnutrition.

Figure 3. How Likely Is It That Your Child Will Become Malnourished if You Do Not Give Your Child Fish to Eat Every Day?

A commonly perceived negative consequence was the poor quality of fish (smoked / re-smoked, frozen / thawed / refrozen),5 with both doers and non-doers listing worms as the most common disadvantage. Probing self-efficacy, doers were 8.1 times more likely to report quality of fish availability as good and not problematic (p < 0.005), while non-doers reported that good quality fish was available, but expensive.

Excluding worms, the majority of doers reported “No disadvantages” of their child consuming fish (p < 0.005), while non-doers shared a variety of reasons, including issues with bones, frequent stooling, vomiting, and fever. Interestingly, non-doers were 9.8 times more likely to state “witchcraft” as a disadvantage than doers, while both non-doers and doers had heard from traditional elders that a child could become a “thief” as a negative consequence of eating fish. Overall, the majority of mothers/caregivers reported not knowing any cultural taboos against children eating fish when directly asked (p = 0.607). Responses across doers and non-doers related to perceived social norms were significantly different regarding “no-one disapproves of them giving fish to their child” and regarding “their mothers disapprove of them giving fish to their child.”

Lastly, non-doers are 3.5 times more likely than doers to respond that it is “very difficult” to remember to give fish daily to children.

Fish Consumption by Pregnant Women

Among pregnant women surveyed, all reported year-round access to and daily consumption of fish, although in limited amounts, and all understood the importance and health benefits of consuming fish. Moreover, all women responded that they did not know anyone who disapproves of them eating fish. Over 90 percent of both doers and non-doers also responded “Yes” when asked if eating fish every day while pregnant is good in the sight of God (“Perception of divine will”).

A major determinant of fish consumption was perceived access and self-efficacy, with 24 percent of non-doers responding it is “Very difficult” to get enough fish to eat every day, and no doers providing this response.

All respondents except one doer (who responded “Don’t know”) believed anemia to be a “Very bad/severe” problem, with the majority of both doers and non-doers believing that fish consumption prevents anemia (p = 0.573). Interestingly, doers were divided over perceived susceptibility to anemia, with “Very likely” and “Not likely at all” each receiving 41 percent of the responses (see Figure 4). Nevertheless, doers were 12.9 times more likely to respond that anemia would affect the development of their baby, stating “Poor child development/important for baby/ important to be healthy when pregnant” (p < 0.005). A limited number of both doers and non-doers understood that anemia could lead to a difficult delivery or put a baby at risk (p = 0.208).

Figure 4. How Likely Is It That You Will Become Anemic if You Do Not Eat Fish Every Day while Pregnant?

Pumpkin Consumption in Children 6–23 Months Old

At the time of the survey, mothers and caregivers reported that pumpkin was scarce, as it was the peak of the dry season. However, a limited number of households currently had pumpkins in their possession or a source for purchasing pumpkins. Significant differences in frequency of consumption between doers and non-doers were observed for both time periods explored. Doers all said that they normally fed their child pumpkin either monthly or more frequently. By contrast, almost all non-doers reported that they only fed their child pumpkin when it is plentiful/during the rainy season or that they never fed their child pumpkin shown in Table 3. Moreover, during the season when pumpkin is plentiful doers fed their children pumpkin much more frequently than did non-doers. The frequency of consumption of pumpkin by children aged 6–23 months is much lower than consumption by pregnant women, even when pumpkin is plentiful, suggesting that mothers may be unaware of the value of pumpkin as a complementary food for young children. Comparing Tables 2 and 3, consumption of pumpkin by children aged 6–23 months is much lower than consumption by pregnant women, even when pumpkin is plentiful, further suggesting the value of pumpkin as complementary food for young children is not well known.

Table 2. Frequency Child Is Fed Pumpkin in the Past Month versus When It Is Plentiful

| Responses | Doers | Non-Doers |

|---|---|---|

| Normally during this month of the year how often do you include pumpkin in what you feed your child?* | ||

| Normally, how often do you feed your child pumpkin when it is plentiful? | ||

| At least once a month | 100% | 8% |

| Only when it is plentiful or in the rainy season | 0% | 63% |

| Never | 0% | 30% |

| At least once a week | 73% | 36% |

| Once every two weeks or once a month | 27% | 40% |

| Never | 0% | 25% |

*These questions were asked both of doers and non-doers.

Table 3. Frequency with which Pregnant Woman Has Consumed Pumpkin in the Past Month versus When It Is Plentiful

| Responses | Doers | Non-Doers |

|---|---|---|

| Normally during this month of the year how often do you eat pumpkin?* | ||

| How often do you eat pumpkin when it is plentiful? | ||

| At least once a month | 94% | 19% |

| Only when plentiful | 6% | 78% |

| Never | 0% | 4% |

| At least once a week | 63% | 53% |

| Once or twice a month | 36% | 45% |

| Never | 0% | 4% |

* These questions were asked both of doers and non-doers.

Issues of availability and access were reported as the limiting factor of consumption, with few differences between doers and non-doers. When asked about ease of feeding their child pumpkin once a month, the majority of both doers and non-doers report providing pumpkin to be “Very difficult” or “Somewhat difficult.” Probed answers centered on money problems, difficulty in finding pumpkin during the dry season, unsuitable soil, being difficult to plant, and poor yields (grasshoppers). Moreover, storing pumpkins was identified as a challenging factor for most respondents; issues included spoilage, lack of a storage facility, rats, maggots, flies, and other bush animals. When pumpkins are plentiful they are traded between households and brought to villages by petty traders. At the time of the survey, pumpkins were harder to find outside the large markets or “lumas” in Magburaka and Matotoka. Mothers/caregivers reported that the price of pumpkins increases in the dry season compared to the rainy season (harvest).

Perceived social norms6 were not observed as influencing consumption, with the majority of both doers and non-doers feeling that “No one/nobody” disapproves of them giving pumpkin to their child (p = 0.817). In addition, the percentage of doers versus non-doers who believe God approves of them giving pumpkin to their child was statistically significant.

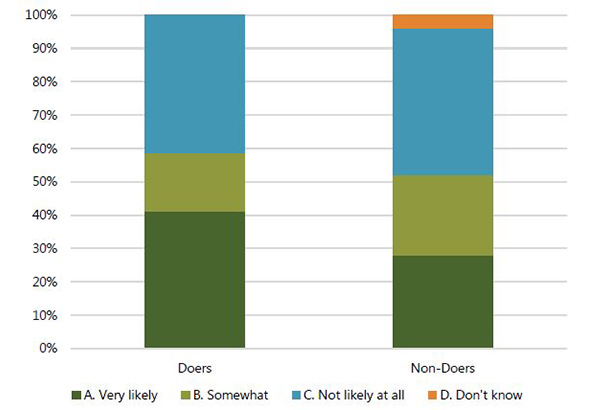

Another significant difference between doers and non-doers was the perceived action efficacy of feeding a child pumpkin, as illustrated in Figure 5 Doers are 2.7 times more likely than non-doers to believe that giving a child pumpkin to eat every month will prevent the child from becoming malnourished. Repeated responses volunteered from non-doers include “Other foods provide the same goodness,” “Child is not sick without pumpkin,” or simply “Child has never tried pumpkin.” When asked which other foods provide the same “goodness” or nutrients as pumpkin, the most common responses from all respondents included banana/plantains, papaya, rice, green leaves, beans, fish, and egg. (See Annex 1).

Figure 5. Do You Believe That Giving Your Child Pumpkin to Eat Every Month Will Prevent Your Child from Becoming Malnourished?

Non-doers were 4.7 times more likely than doers to list “rashes/scratches the body or skin” as a disadvantage. Furthermore, doers were more aware of the benefits of pumpkin than non-doers, with perceived advantages including “heals rashes” and “freshens skin,” along with “prevents constipation” and “encourages normal stooling,” and “clears the stomach” and “clears stomach sicknesses.”

Pumpkin Consumption by Pregnant Women

Over three-quarters of non-doers reported only eating pumpkin “when it is plentiful,” compared with 6 percent of doers (p < 0.005), as illustrated in Table 3. During the season when pumpkin is plentiful both doers and non-doers consumed pumpkin with essentially the same frequency.

Interestingly, doers were 3.2 times more likely than non-doers to list the good taste/good feeling of pumpkin as an advantage.

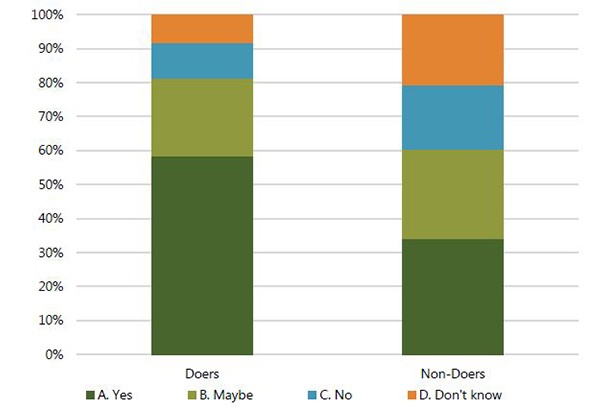

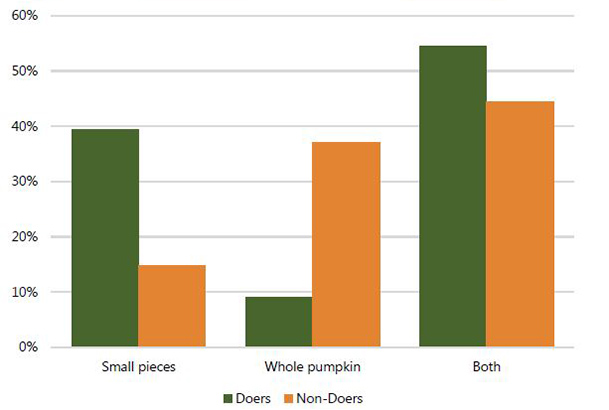

The most significant distinction between doers and non-doers was access. The majority of both doers and non-doers vocalized issues of availability at time of survey. When probed regarding perceived access, most non-doers reported pumpkin was not always available in their village or was unavailable unless they traveled to the lumas (markets) at Magburaka or Matotoka (p < 0.005). One-third of doers stated that they did not purchase pumpkin, but rather relied on growing their own pumpkin, which no non-doers reported. Non-doers were 3.7 more likely to than doers to answer it is “very difficult” to get enough pumpkin for them to eat it every month, identifying “limited availability/seasonal access” as the major restriction (p < 0.005). In addition, non-doers were more likely to purchase whole pumpkins (possibly limiting the frequency of purchase) while many doers reported purchasing small pieces/slices of pumpkin (Figure 6).

Figure 6. How Is Pumpkin Sold/Purchased?

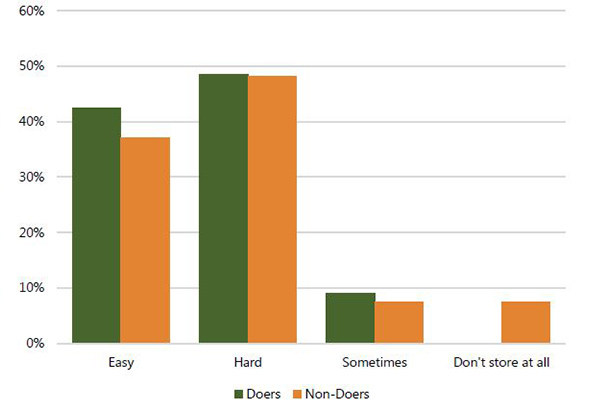

The pregnant women respondents identified storage problems corresponding to those indicated by mothers/caregivers of children aged 6–23 months, including lack of a storage facility and issues of rats. Approximately one-half of both doers and non-doers believed pumpkin is hard to store (see Figure 7). Notably, within the same village a large number of respondents stated that storing pumpkins was not difficult, indicating a gap in knowledge sharing.

Figure 7. Is Pumpkin Hard to Store?

In terms of perceived social norms, there was no statistically significant difference between doers and non-doers reporting relatives and neighbors who disapprove of pregnant women eating pumpkin, although doers were 8.5 times more likely than non-doers to share that health workers/nurses approved of pumpkin consumption while pregnant (p < 0.005).

Conclusions and Recommendations

The team discovered pumpkin not only plentiful in the rainy season, but also popular. However, at the time of the survey, general scarcity, prohibiting year-round consumption by both pregnant women and child 6–23 months, was evident. The key determinants for pumpkin consumption included accessibility, cost, and storage. The issue of storage requires further investigation to understand the potential for year-round availability and reduced spoilage; various methods of storage were proposed, but knowledge sharing between neighbors was poor. Additionally, some traders must have good storage techniques since they are able to maintain effective storage for off-season sales, and thereby earn higher prices. Knowledge sharing within communities should be promoted to encourage improved yields and effective storage.

The importance of pumpkin was not widely communicated within these communities, with predominantly doers (both pregnant women and mothers/caregivers) perceiving nurses and health workers to approve of eating pumpkin. In particular, pumpkin needs to be further promoted as a beneficial complementary food; it is currently undervalued for children aged 6–23 months, even when pumpkin is plentiful and widely consumed by pregnant women and other household members. Numerous households that grew, and apparently knew how to store, pumpkins deplete their stocks early in dry season due to low quantity produced. Increasing knowledge on the benefits of pumpkin through mother support groups and other channels could eventually increase demand and motivate farmers to increase production.

Although fish is widely consumed daily within a sauce, the quantity consumed per person is low. Overwhelmingly, both pregnant women and mothers/caregivers believed that fish is good for a healthy life. Limited access and availability, affordability of the preferred varieties of fish, along with poor quality, were the biggest barriers to daily and year-round fish consumption. The purchasing power of mothers, caregivers, and pregnant women is constricted not only by the price, but also limited by lack of access to safe, quality (smoked/frozen) fish.

Fish is sold many days or even weeks old, with maggots being seen on occasion. Most mothers fear giving their children fish because of the poor quality and/or improper handling of traders. Addressing gaps in research and innovation mitigating concerns of sanitation and hygiene would have significant impact not only at the household level but also for traders and others who lose fish to spoilage. Furthermore, the health benefits and safety of powdered fish (produced on a large scale) needs further investigation to determine the potential of increasing year-round access to fish for children aged 6–23 months. This could address major safety concerns of mothers/caregivers, specifically those who avoid giving their babies fish for fear of bones. Against this current backdrop, caution should be exercised when advising mothers/caregivers to mix fish into complementary food.

Lastly, numerous caregivers encountered did not understand when to start complementary feeding, thus giving their children only breast milk and water past six months, including some cases with children over 11 months of age. This could be addressed by supporting mother support groups and conducting refresher trainings for those responsible for home visit and counseling, while also promoting wider participation at the household level. Alternatively, multimedia messages could successfully address issues of conflicting or confusing messaging, potentially by designing and showing Pico videos at the community level.

To view the annex, please download the full report above.

Footnotes

1 Davis Jr., Thomas P., (2004). Barrier Analysis Facilitator’s Guide: A Tool for Improving Behavior Change Communication in Child Survival and Community Development Programs, Washington, D.C.: Food for the Hungry. View here.

2 Taken from: Kittle, Bonnie. 2013. A Practical Guide to Conducting a Barrier Analysis. New York, NY: Helen Keller International. View here.

3 Determinants taken from: Kittle, Bonnie. 2013. A Practical Guide to Conducting a Barrier Analysis. New York: Helen Keller International. View here.

4 Results from the first half day were excluded from the analysis.

5 SPRING. 2016. Barriers and Facilitators to Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture Focusing on Fish and Pumpkin Value Chain in Tonkolili. Arlington, VA: Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project.

6 The perception that people important to an individual think that he /she should or should not do the behavior