A Report on the Key Findings of the Formative Research Conducted at the Initiation of the Project in 2012

Executive Summary

SPRING is working in India in collaboration with Digital Green, a U.S.- and India-based organization, spreading across 30 villages in the Keonjhar district of Odisha state. This collaboration focuses on adapting Digital Green’s innovative community media model to address nutrition in the first 1,000 days, reaching new audiences through mobile video screenings and facilitated discussions, with adoption of key behaviors verified through home visits.

In November 2012, SPRING and Digital Green completed a qualitative study in purposely selected villages in Keonjhar district to identify current social and cultural determinants, practices, and knowledge on maternal, infant, and young child nutrition (MIYCN). The information was collected to help guide the development of community-based videos promoting optimal nutrition practices to improve the nutritional status of pregnant and lactating women and young children.

The specific objectives of the qualitative research were to:

- Identify existing family relationships in terms of decision making. (Who makes decisions regarding nutrition? Who makes decisions regarding health? What are some of the relationships linked to gender and/or caste?)

- Identify the current MIYCN practices and barriers that need to be addressed, such as food misconceptions (taboos); knowledge related to the nutrition and health of pregnant and breastfeeding women and children under two years of age; and influencing individuals.

- Identify the major nutritional issues adolescent girls and women face, including societal structures, taboos, barriers, as well as promising practices to build upon.

- Understand the current hygiene practices with a focus on handwashing with soap.

- Identify sources of information currently used by adolescents, pregnant women, and breastfeeding mothers, and also how current services and providers are perceived (Integrated Childhood Development Services [ICDS], Anganwadi workers [AWWs], accredited social health activists [ASHAs], and auxiliary nurse midwives [ANMs]).

- Identify the perceptions of community members and video production and dissemination teams regarding the Digital Green videos.

This report is comprised of five distinct parts: Part 1 presents the current nutrition situation in India; part 2 reviews the formative research methodology; part 3 shares the key findings of this qualitative study; part 4 is a discussion of those findings; and part 5 summarizes the conclusions and recommendations.

Summary of Findings

As identified in this formative research, many factors affect optimal MIYCN practices in Keonjhar district, underscoring the fact that improving MIYCN practices goes far beyond increasing knowledge. These factors include the following:

- Many women have limited agency to decide when to eat, how much to eat, or when to rest, due in part to the traditional gender-related social norms. It is key to get a better understanding of how to ensure that breastfeeding mothers have enough food to eat while breastfeeding and have access to a healthy diversity of foods.

- Family organizational structures can also create confusion, especially when a mother-in-law’s advice contradicts that of the ASHAs and AWWs.

- Although lack of knowledge of optimal MIYCN practices is not the clear driver behind current MIYCN behaviors, this research indicates that there are areas where knowledge, information sharing, and skills need to be strengthened, such as exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding.

- It is important to reiterate that there are many traditional practices and food taboos (some harmful and some essentially harmless or neutral) that dictate what women can eat while they are breastfeeding, specifically for the first six months of the life of the child.

- Another important consideration for prioritizing nutrition video content is the strongly held belief that iron–folic acid (IFA) supplements, if taken during pregnancy, lead to bigger babies, with negative consequences. With high rates of anemia in India, this is a key misconception to address.

- Health workers are critical in supporting optimal nutrition for women and children; at times they are trusted by the community but at other times they are not. Some AWWs are perceived as actually using some of the government schemes for their own benefit. The ASHAs can be a reliable source of information but only if they provide outreach services.

Key Recommendations

The research was also able to highlight key behaviors that seem “ripe for change” and that could be further explored through the development and use of community videos:

- Promoting exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months of life, explaining that breast milk provides sufficient liquid to the baby even during the hot months; that women make more milk when the child breastfeeds; and that when a child is ill, she/he needs to be breastfed more often.

- Promoting the health of breastfeeding mothers while encouraging the reduction of women’s workload during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

- Developing videos that address nutrition-related issues focused on the first 1,000 days and strengthening support for mother/child pairs following the first 21 days.

- Addressing maternal nutrition during pregnancy and postpartum (promoting iron-rich foods), promoting one extra meal, promoting rest, and strengthening adherence to recommended IFA supplementation by addressing some of the misconceptions identified (e.g., the fear of having too big a child).

- Developing videos teaching mothers about how critical complementary foods are and how to improve their quality with locally grown foods.

- Strengthening the role of husbands and fathers as supportive partners and engaging them in video viewing and discussions.

- Targeting mothers-in-law when developing nutrition videos, recognizing their roles in childcare practices, since they are powerful decision makers and gatekeepers in the households.

- Engaging community health agents (ASHAs and AWWs) in reviewing the content of the videos and perhaps featuring them as “stars” in the videos given their specific role in the community.

- Promoting handwashing with soap as a critical hygiene practice.

1. Introduction and Background

1.1 Overview of the SPRING/Digital Green Collaboration and Feasibility Study

SPRING is a five-year USAID-funded Cooperative Agreement to strengthen global and country efforts to scale up high-impact nutrition practices and policies and improve maternal and child nutrition outcomes, with a focus on the first 1,000 days. SPRING has committed to identifying and testing proven or highly promising social and behavior change communication (SBCC) tools and models to promote optimal maternal, infant, and young child nutrition (MIYCN). In October 2012, SPRING entered into a formal partnership with Digital Green, a U.S./India-based nongovernmental organization (NGO), to test the adaptation of an innovative “human-mediated digital learning approach” currently being used by Digital Green to promote the diffusion of improved agricultural practices.

In November 2012, SPRING and Digital Green completed a qualitative study in purposely selected villages in Keonjhar district to identify current social and cultural determinants, practices, and knowledge on MIYCN. The research findings also informed the development of a community nutrition training package for use in sensitizing a range of community agents involved in the production of context-specific nutrition and hygiene-focused video content. Furthermore, the aim of the SPRING/Digital Green collaboration and qualitative study was to establish whether or not the current Digital Green agricultural extension platform could be adapted for nutrition content, and to document the process for use in other settings. The nutrition-focused videos feature mothers and other community members, speaking in their own language, about their individual experiences with selected key nutrition and hygiene practices. The approach uses a “dialogue” or “reflective” process among peers, rather than a traditional nutrition education approach of outside “experts” informing clients. When possible, the approach uses positive deviants from the communities who are already practicing the recommended behaviors as the main actors for the videos. Data on intention to adopt and verification of adoptions or promotions of key behaviors are then collected and organized using a near-real-time analytical dashboard, which facilitates informed decision making and the improved design of subsequent videos.

The adaptation of the Digital Green model was piloted in 30 villages in two blocks of Keonjhar district of Odisha state: Patna and Gartageon. This pilot was also supported by the Voluntary Association for Rural Reconstruction and Appropriate Technology (VARRAT), the local community-development NGO partner working with Digital Green in Odisha.

1.2 Maternal and Child Health and Nutrition Situation in India

Although India is among the top five countries in terms of absolute numbers of maternal deaths, encouraging progress has been made in reducing the burden of maternal and child death. During the last decade, child mortality rates have dropped by 45 percent in India. In 1990, when the global under-five mortality rate was 88 per 1,000 live births, India also carried a high burden of child mortality: 115 per 1,000 live births (Office of Registrar General, 2013). Two decades later, in 2010, India’s child’s mortality rate of 59 per 1,000 live births was close to the global average of 57. At the national level, the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) dropped from 212 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2007–2009 to 178 in 2010–2012, a decline of 16 percent (Maternal Mortality Bulletin 2013). Nevertheless, much remains to be done to improve child and maternal health and survival in India. There are still 56,000 maternal deaths each year and about two-thirds of these occur in six states, one of which is Odisha. With the current under-five mortality rate, about 1,580,000 children in India do not reach their fifth birthday. Of these, 56 percent of children die in the first month of life (880,000 children), and 79 percent (1,250,000) die within their first year, including the neonatal period (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, January 2013).

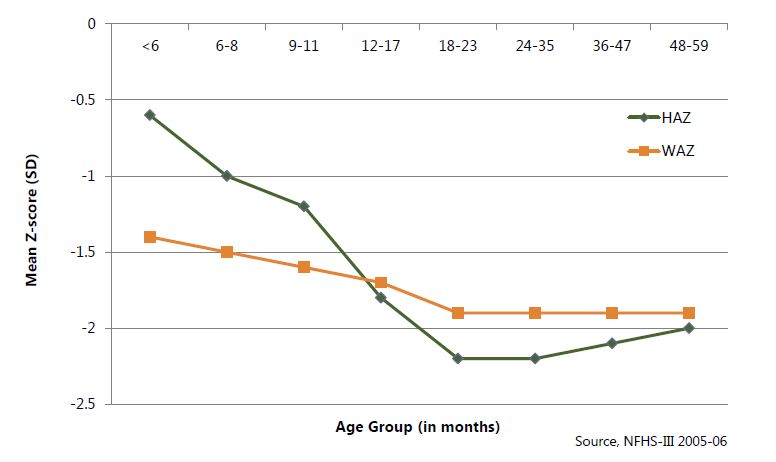

In terms of nutrition, of the 150 million undernourished children worldwide, more than one-third live in India (UNICEF 2013). The most recent National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), conducted in 2005–2006, indicates that 48 percent of children under five are stunted and 20 percent of children under five are severely malnourished, as measured by wasting (IIPS and Macro International 2007). The prevalence of wasting in India is twice as high as the average prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa and seven of 10 children in India are anemic. Undernutrition occurring in the first two years of life is particularly difficult to overcome later in life. The NFHS-3 survey data show that during the first six months of life 20–30 percent of Indian children exhibit signs of undernutrition, peaking at 20 months of age (IIPS and Macro International 2007). In India, 56 percent of severe wasting occurs before a child reaches the age of two years, which underscores the importance of adequate nutrition in the first 1,000 days of a child’s life (Coalition for Sustainable Nutrition Security in India 2008). Figure 1 shows the weight-for-age and height-for-age of Indian children through 35 months of age, illustrating the severe nutritional deficits that occur in this critical window.

In India, one-third to one-half of child deaths can be attributed to undernutrition (Naandi Foundation 2011). When not resulting in child deaths, undernutrition causes stunted physical growth and cognitive development, deficits that result in economic losses equivalent to an estimated 3 percent annually of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) (Naandi Foundation 2011).

Figure 1: Weight-for-age and height-for-age, Indian children up to 35 months of age

Source: IIPS and Macro International 2007

Additionally, among underweight women, 44 percent are moderately to severely underweight.

Anemia in India

Globally, India ranks high in the prevalence of anemia, with a national prevalence of 74.3 percent, making it a severe public health problem (WHO n.d.). Fifty-nine percent of pregnant women in India are anemic, and it is estimated globally that anemia is the underlying cause for 20–40 percent of maternal deaths (Viteri 1994). The NFHS-3 shows that anemia is widely prevalent among all age groups, as illustrated in Table 1. The prevalence of anemia among adolescent girls (Hb < 12 g/dl) and boys (Hb < 13 g/dl) is alarmingly high; with girls being most at risk (56 percent of adolescent girls aged 15–19 years versus 30 percent of boys aged 15–19 years). Anemia prevalence among children aged 6–35 months has actually increased between the two most recent NFHS surveys from 74.3 percent (NFHS-2) to 78.9 percent (NFHS-3), indicating that seven of 10 children aged 6–59 months in India is anemic (IIPS and Macro International 2007).

Table 1: Prevalence of Anemia among Different Age Groups in India

| Age Group | Prevalence of Anemia (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| Adolescent Girls | |

| Children (6–35 months) | 78.9 |

| Children (6–59 months) | 69.5 |

| All women (15–49 years) | 55.3 |

| Ever-married women (15–49 years) | 56.0 |

| Pregnant women (15–49 years) | 58.7 |

| Lactating women (15–49 years) | 63.2 |

| 12–14 years | 68.6 |

| 15–17 years | 69.7 |

| 15–19 years | 55.8 |

Source: IIPS and Macro International 2007

Undernutrition in Odisha

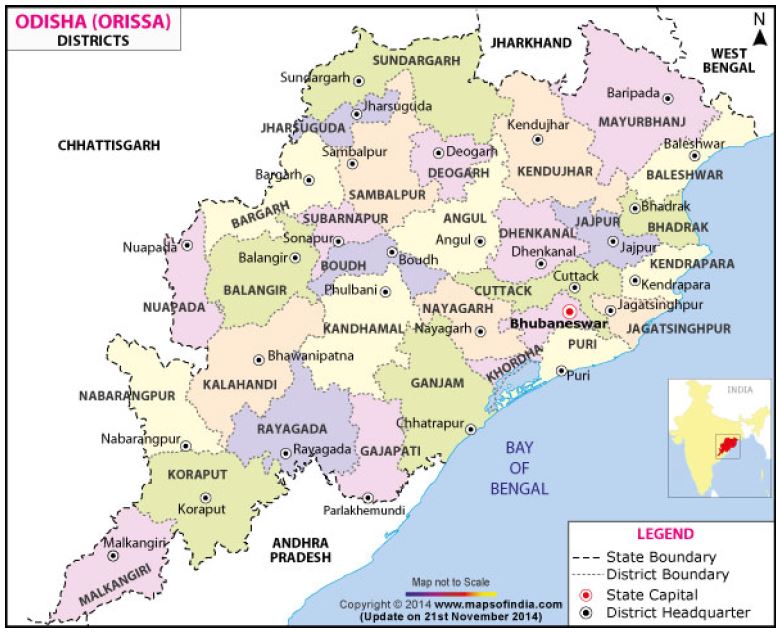

On the eastern coast of India lies Odisha, one of the country’s least-urbanized states (Figure 2). In the last few decades, however, the state has benefited from growing industrialization, with an average income that has almost tripled; however, Odisha has the highest percentage of its population living below the poverty line among all India states (UNICEF 2012). Odisha’s per capita income and household income are significantly lower than the national averages. While average household income at the national level is 27,857 Indian rupees (INR), it is INR 16,500 in Odisha. The national average capita income is INR 5,999; in Odisha it is INR 3,450. Based on the percentage of rural population consuming less than 1,890 kilocalories per day, Odisha has moved from being classified as low food insecure (11.1 percent) in 1999–2000 to moderate food insecure (15.4 percent) in 2004–2005. In the same time period, national levels of food insecurity fell from 15.1 percent to 13.2 percent (MSSRF/WFP 2008).

Over 80 percent of the workforce in Odisha is employed in the agricultural sector, and 50 percent of the GDP of India comes from Odisha. Twenty percent of households in Odisha belong to a scheduled caste (SC), 23 percent to a scheduled tribe1 (ST), and 27 percent to other backward classes (OBCs) (IIPS and Macro International 2008).

Figure 2: Map of Odisha’s districts

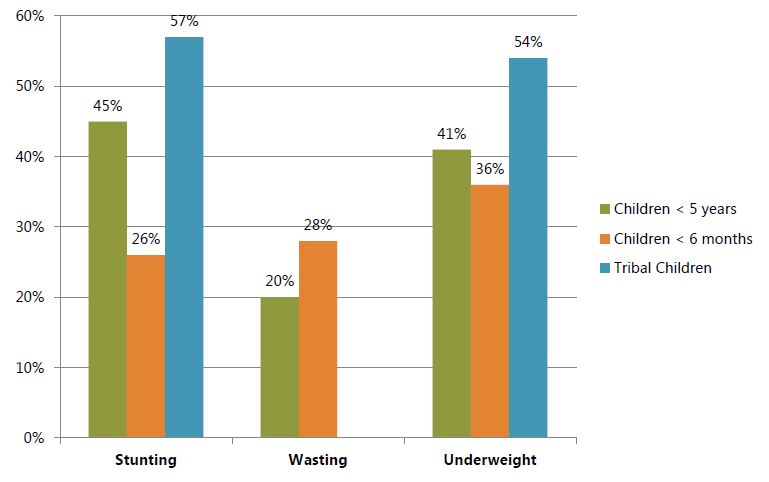

Odisha’s infant and under-five mortality rates, at 65 and 91 per 1,000, respectively, are higher than the national averages. Despite declining rates in mortality in the past few decades, one in 11 children in Odisha will die before reaching the age of five (IIPS and Macro International 2008). As seen in Figure 3, children in Odisha, particularly children of STs, exhibit alarmingly high rates of undernutrition. Tribal groups in India are among the most underprivileged and comprise about 8 percent of the population. The STs in Odisha, also known as Adivasi (the Sanskrit word for indigenous) communities, have double the unemployment rate of non-Adivasi people, and only one-third of children from STs receives a primary education. Data indicate that nearly 75 percent of the tribal population in Odisha is below the official poverty line (Mehta 2011). Tribal communities characteristically have higher mortality and morbidity rates and poorer access to health services than non-Adivasi communities (IIPS and Macro International 2007, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare 2013). Children from STs are about 1.5 times more likely to die before their fifth birthdays than those from SCs (Mehta 2011). Nationally, 57 percent of ST children are malnourished, 28 percent are severely stunted, and 54 percent are underweight (Mehta 2011). In 2005–2006, under-five mortality rates for children from STs were almost twice as high as those of nontribal children. This under-five mortality rate was also 1.5 times higher than for children from SCs.

Figure 3: Children's nutritional status in Odisha

Source: IIPS and Macro International 2008

NFHS-3 shows that only one-half of the children under six months of age are exclusively breastfed, although the average breastfed child is breastfed for 34 months. Fifty-five percent of babies are put to the breast within the first hour of life to receive colostrum; however, there is a significant prevalence (42 percent) of supplemental feeding within the first few weeks of life. About 56 percent of children aged 6–23 months are fed the recommended minimum times per day, but only 44 percent are fed from the minimum number of food groups per WHO recommendations (IIPS and Macro International 2008). Anemia is a serious health issue in Odisha, with a prevalence rate among women of reproductive age at 62.8 percent, compared to the national average of 56.1 percent (Panigrahi and Sahoo 2011). Additionally, close to 65 percent of children 6–59 months in Odisha are anemic and this prevalence has risen since the previous NFHS (IIPS and Macro International 2008).

Health in Keonjhar District

The SPRING/Digital Green project site is located in Keonjhar district, which is comprised of 2,132 villages. Eighty percent of the population in Keonjhar lives in rural areas and engages in traditional agriculture, and more than three-quarters of the population live below the poverty line (Government of Odisha 2012). The infant mortality rate in Keonjhar is 58 per 1,000 live births, and the under-five mortality rate is listed at 85 per 1,000 live births in the latest official data (Ministry of Home Affairs 2011). Keonjhar has a high rate of undernutrition compared to other districts in the state, with moderate to severe undernutrition at a rate of 20.46 percent. Only 24.6 percent of children are exclusively breastfed for six months, meaning that the remaining almost 86 percent receive supplementation of breast milk with water and other fluids during the first six months. On average in the district, children are not fed vegetables or fruits until 8.5 months or solid foods categorized as “adult” foods until 9.4 months (Ministry of Home Affairs 2011).

2. Formative Research Methodology

2.1 Goal and Objectives

In November 2012, SPRING and Digital Green completed a qualitative study in purposely selected villages in Keonjhar district to identify current social and cultural determinants, practices, and knowledge on MIYCN. The information was collected to help guide the development of community-based videos promoting optimal practices to improve the nutritional status of pregnant and lactating women and young children, with a focus on the first 1,000 days. The specific objectives of the study were to:

- Identify existing family relationships in terms of decision making. (Who makes decisions regarding nutrition? Who makes decisions regarding health? What are some of the relationships linked to gender and/or caste?)

- Identify the current MIYCN practices and barriers that need to be addressed, such as food misconceptions (taboos); knowledge related to the nutrition and health of pregnant and breastfeeding women and children under two years of age; and influencing individuals.

- Identify the major nutritional issues adolescent girls and women face, including societal structures, taboos, barriers, as well as promising practices to build upon.

- Understand the current hygiene practices, with a focus on handwashing with soap.

- Identify sources of information currently used by adolescents, pregnant women, and breastfeeding mothers, and also how current services and providers are perceived (Integrated Childhood Development Services [ICDS], Anganwadi workers [AWWs], accredited social health activists [ASHAs], and auxiliary nurse midwives [ANMs]).

- Identify the perceptions of community members and video production and dissemination teams regarding the Digital Green videos.

2.2 Selection of Research Sites

For the formative research, a total of six villages (three in each block) were selected from the 30 priority villages that were selected to participate in the one-year feasibility study. The six villages were purposely selected based on the percentage of scheduled tribe. The population rate of STs in the program villages ranges from 100 percent to 40 percent; thus, three villages in each block were identified to represent this range: one village having a high ST population, one with a medium ST population, and one with a smaller ST population. In addition to representing the cultural diversity, these six villages were selected from various Gram Panchayats (village councils) to also capture information about Panchayat systems and their effectiveness. The team of researchers agreed to select villages where the Panchayat had already been actively addressing nutrition in their communities, as it was agreed from the start that the pilot would be conducted in villages that showed promising leadership in health promotion. Further, as the pilot was limited in time (one year), it needed to quickly show evidence indicating that integrating nutrition within an agricultural SBCC platform might be feasible. See Table 2 for names of selected villages for the qualitative research.

Table 2: Selected Villages for Formative Research in Kehonjar District, Odisha State, Including Percentage of Households from Scheduled Tribes

| Name of Block | Name of Panchayat | Name of Village |

|---|---|---|

| Patna | Dumuria | Baidabaja (100% ST) |

| Erendei | Begunakhaman (34% ST) | |

| Palanghati | Kumulabahali (71% ST) | |

| Ghatagaon | Santarapur | Chatia (74% ST) |

| Santarapur | Raghubeda (92% ST) | |

| Manoharpur | Gandasila (74% ST) |

2.3 Research Team

The nine-person research team was made up of lead researchers, including a Senior Nutrition Advisor from Save the Children India, the Nutrition Program Manager from Digital Green, a Global Advisor from Save the Children US, and key interviewers with extensive experience at the community level in agricultural, health, and social sciences. Interviewers were divided into three teams, with an equal gender representation on each team. Two of the teams were primarily responsible for conducting 12 focus group discussions (FGDs), while the Global Advisor conducted 16 in-depth interviews (IDIs) with the local NGO partner, VARRAT’s Program Director as a translator. SPRING trained the research teams on the objectives of the research, the tools, data collection, and recording of information. The data collection was conducted for four days in the field. At the end of each day, the teams met for two hours to debrief, highlight findings, and review questions or issues.

2.4 Research Methodology

The methodology was developed in collaboration and extensive consultation with the local partner (VARRAT), and Digital Green. The research protocol was submitted to the internal review board (IRB) at John Snow, Inc. (JSI), for approval and to ensure that the research objectives and tools met all ethics criteria and would not create harm for respondents and communities involved in the research. Expedited IRB approval was received under category 7 after a formal review of protocol and tools. The tools were developed in English and translated into Odia. All teams had native Odia speakers; the only person not speaking Odia was the Global Advisor, who worked with a translator.

Data collection was organized around two phases. During the first phase, in-depth interviews were conducted with key informants to inform the research questions and tools. Key informants included the Director of Programs of VARRAT, the UNICEF Regional Coordinator, one ANM, one AWW, and members of the VARRAT video production team.

The second phase included a mix of IDIs and FGDs, all conducted in Odia (Table 3). All participants signed consent forms before each FGD or IDI began. Extensive verbatim notes were taken in Odia and then translated into English. FGDs and IDIs were conducted with primary target respondents, secondary targets, and representatives of community systems. Specifically, the research included nine groups of participants:

- Pregnant women

- Breastfeeding women with children less than six months old

- Breastfeeding mothers of children between six months and two years old

- Mothers-in-law

- Fathers of children less than two years old

- VARRAT community service providers and other staff

- Anganwadi workers

- Nutrition Committee members

- Gram Panchayat leaders

Table 3: Summary of FGDs and IDIs Conducted during the Second Phase of Qualitative Research

| Focus Group Discussions: 6–15 People | No. Held |

|---|---|

| In-Depth Interviews | |

| Pregnant women | 2 |

| Breastfeeding mothers/child < 6 months | 2 |

| Breastfeeding mothers/child 6 months to 2 years | 2 |

| Mothers-in-law/grandchildren < 2 years | 1 |

| VARRAT community service persons | 1 |

| Anganwadi worker | 1 |

| Village Health Committee member | 1 |

| Nutrition Committee | 1 |

| Gram Panchayat leader | 1 |

| Pregnant women | 4 |

| Breastfeeding mothers/child < 6 months | 4 |

| Breastfeeding mothers/child 6 months to 2 years | 4 |

| Fathers/children < 2 years | 4 |

| Director of Programs, VARRAT | 1 |

| UNICEF Regional Coordinator | 1 |

| Auxiliary nurse midwife | 1 |

| Anganwadi worker | 1 |

| Members of the VARRAT video production team | 1 |

3. Study Findings

The research findings have been organized by the six specific objectives outlined for the study.

3.1 Objective 1: Identify Existing Family Relationships in Terms of Decision Making

FGDs and IDIs were conducted with pregnant women, lactating mothers, mothers-in-law, and husbands to understand how families are organized, and which individuals in the family are decision makers, gatekeepers, and/or influencers to target for the promotion of key behaviors. From the interviews, it is clear that most families provide a source of comfort and support to women and children and ensure that children are never left alone, even though women have to go back to work very soon after giving birth. The families interviewed are clearly organized around some power and labor sharing responsibilities and are both a source of support and advice, though at times erroneous. Additionally, it was evident that the dynamics within families are evolving in India. This research focused on villages within a traditional rural setting in Keonjhar, but even in this setting, an increasing number of women have access to education, which is influencing women’s agency and decision making regarding their health and children. The Government of India (GoI) is also focusing on strengthening primary care systems and community health programs to ensure that families have access to education and services at the community level—so, although family members play an important role in deciding what women and children eat, community health workers such as ASHAs, AWWs, and ANMs are playing an increasing role in building understanding among families about optimal MIYCN practices.

3.1.1 Role of Mothers-in-Laws (Sassous): A Source of Authority, Expert Advice, and Support

In traditional Indian culture, after marriage, many women live with their husband’s parents, and at times with their husband’s brothers and their wives. It is not unusual to see nine to 12 people across three generations living under one roof. During the IDIs and FGDs, most women, including pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers, and mothers-in-law, reported that their families were organized around this extended pattern, where daughters-in-law move in with the husband’s parents. Both sets of respondents (mothers-in-law and pregnant and lactating women) shared that within this extended family structure, there is a nonformal division of labor; that this structure provides support to pregnant women and women who have just given birth; and where mothers-in-law and elderly parents play an active child caring role while the younger generation goes back to work in the fields.

In terms of labor distribution in the household, usually the youngest daughter-in-law has an overwhelming burden of work. She is expected to cook and serve meals, and in most cases eats last, after everyone else has been fed. All pregnant and breastfeeding mothers reported that they really don’t have any decision-making power within the extended household, and that their mother-in-law is the one who makes decisions for them. However, for most of the respondents, they also shared that they trusted the advice of their mother-in-law, as someone with years of experience raising families. The mother-in-laws were seen as the main authority, a source of expert advice and support to the other women and children in the family, playing an active role in organizing the labor distribution within the home.

My mother-in-law is very good. I did not feel frightened when I was in the hospital as my mother-in-law was there. My mother-in-law supports me the most. She helps me with cooking and cleaning utensils.

-IDI with mother with child less than six months old

The caregiver of the lactating mother is very powerful, it is usually the mother-in-law and husband, but the mother-in-law is more powerful than the husband. The mother-in-law is the primary caregiver of the pregnant and lactating mother. The mother-in-law is usually preparing the food for the lactating mother when she returns home.

-KII [key informant interview] with ANM

3.1.2 Role of Mothers-in-Law Specifically Related to Nutrition during Pregnancy and Also for Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices

Many pregnant women and breastfeeding women reported that at first they were not sure what to eat during their pregnancy and postpartum period. They reported following the guidance of their mother-in-law in terms of deciding which foods they should eat while pregnant and when breastfeeding the new child. Many pregnant women reported that their mother-in-law decides which foods they can eat during pregnancy, and more importantly, it appears from the interviews that mothers-in-law decide what lactating mothers can eat until the time the child crawls.

Many pregnant and breastfeeding mothers reported trusting their mother-in-law and seeking her advice for rearing their children, specifically in terms of feeding the infant and young child. Others reported, however, that times were changing and that they, themselves, decided what to eat. Although in many households mothers-in-law appear to decide what pregnant and new mothers eat, one has to also take into consideration that many young women are seeking advice from others, such as ASHAs and ANMs, in caring for themselves and their children.

My mother-in-law decides what I can eat, and how often. My mother-in-law tells me the child will get sick if I eat different foods. If I eat more, she says I cannot digest the food and the child will have digestive problems. I believe my mother-in-law, I won’t be able to digest the food. I believe my mother-in-law, she knows. I will tell my children this later when I am a mother-in-law.

-IDI with mother with child less than six months old

My mother-in-law told me to take two meals a day because the baby eats small amounts, since the baby is small. When the baby grew a bit more, then my mother-in-law said I could eat more times, three times a day.

-FGD with mothers of children less than six months old

During the first month, I can only eat twice a day, once in the morning and once in the evening. At first, I feel hungry, but then it becomes a practice. There is a ritual, this is part of my family, it takes three to five days to get used to the food and being hungry, it takes some days to settle, but even if we are hungry we cannot do anything, this is what is decided by the elders. [What does your husband think?] He goes by his mother. This is a family tradition.

-IDI with mother with child less than six months old

I don’t know what to do but the elders tell me what to do and I do what they say to do. The elders tell me what to eat. Everyone says I need to eat the tablets [referring to iron folate tablets], so I eat the tablets. I take them and go to sleep so I have no problem with the tablets.

-IDI with pregnant woman

Mothers-in-law reported that their role is to support their daughters-in-law, as they have been mothers before and know from previous experience what women and children require to remain healthy. Mothers-in-law reported that they give nutritional advice to the pregnant and lactating mothers and they are trusted within the home, because they have experience. However, during the FGD discussion with mothers-in-law, it was clear that mothers-in-laws’ beliefs differ, with some stating that pregnant and breastfeeding mothers need to eat less to ensure that the new baby does not grow too big or to ensure that the breastfeeding baby can digest the food the mother eats. Some mothers-in-law reported fearing that “taking the IFA would make the baby too big for delivery.” Others reported that pregnant and breastfeeding mothers should eat more often and take their IFA regularly.

Pregnant women should eat more so that it would help the child be stronger and better. Yes, it is better for them to eat more, and also to take the good tablets from the hospital.

-FGD with mothers-in-law

All of the mothers-in-law during the FGD reported that some foods (referred to as “cold foods”), when consumed while breastfeeding the child, might make the child sick. They also reported that ripe raw papaya, okra, and white eggplant, if consumed by the lactating mother before the child is six months of age, would give a cold to the child.

Similar beliefs exist about certain foods that can give the baby a fever.

My mother-in-law tells me that I cannot eat other foods, because if I eat them the body of the baby will get hot, the baby will have a fever.

-IDI with mother with child less than six months old

It is also important to note that although all mothers-in-law reported that their daughters-in-law were exclusively breastfeeding, when probed, they explained that in fact the newborn received some additional liquids, or foods, based on traditions. The mothers-in-law listed honey, gripe water, and cow’s milk as expected to be given to the newborn when visitors come to welcome the new child.

3.1.3 Role of Mothers-in-Law Regarding Delivery and Postpartum Care

In addition to giving advice to pregnant women within their households, mothers-in-law play a critical role in decisions around delivery and postpartum care. It appears from the interviews that although ASHAs and ANMs are consulted during the pregnancy, the final decision for delivery is made in consultation with the mother-in-law. During the FGD with mothers-in-law, three of four reported that they knew that hospital delivery is better but they also shared that they felt that nowadays women go to the health center to deliver as they don’t know how to endure pain. “Woman go to the clinic as soon as there is pain.” Although the mothers-in-law did not clearly state that enduring pain can be a sign of pride for the household, they did report that “in [their] times [they] delivered at home and could endure the pain.” Although there is a need for more research, mothers-in-law might also be influencing where women give birth. Many of the lactating mothers interviewed reported having given birth at home.

The baby was born at home. This is my first baby, home is good. Lots of people in my family talked about where the baby would be born. My mother-in-law decided where the baby would be born.

-IDI with woman with child less than six months old

Once the child is born, new mothers who deliver at the clinic often come back the same day to the house. They are generally confined to one room in the house for the first 21 days. This is a time of rest for the new mother and the child. The mother-in-law moves into the room and takes on the responsibility to care for the newborn and the mother. The mother-in-law washes both her grandchild’s and daughter-in-law’s clothes so that the mother and child do not catch a cold. The mother-in-law also prepares food and feeds her daughter-in-law. Some respondents shared that in their community, they make a fire in the room where the mother and child are staying and warm up a cloth to wipe the baby. The mother also massages herself with oil during this period. The baby is given an oil massage twice a day, called bhumi shek, which involves pressing down the navel with a clean piece of cloth that is first pressed to a clean portion of the floor, which has been specially cleaned for this purpose during this period. The baby is given a bath with turmeric and warm water seven days after the initial period of confinement. Mothers are also restricted from taking a bath during their confinement. They are allowed to change clothes and wash hands and feet regularly. This 21-day period is an important period for the new mother as it gives her an opportunity to rest and be with her child. After this period, she is expected to go back to work, and her mother-in-law, with the help of other women in the household, takes care of the infant.

During the 21 days, our mothers-in-law sleep with us and the child in the same room. The mother-in-law does the work for the child. After 21 days, everybody can touch us.

-FGD with breastfeeding women

When the mother and child come back to the house, we (sassous) take care of them. They rest for nine days. The mother does not go out, and someone (mother-in-law, sister-in-law) stays with her. There is a fire in the room. We massage the child, and we warm the cloth by the fire. We put the cloth on the baby’s body so the baby’s body is warm. We warm up the child with the fire and massage with turmeric.

-FGD with mothers-in-law

3.1.4 Role of Husbands

Though husbands were not reported as playing such an active role in decision making regarding maternal and child health as the mothers-in-law, many pregnant and breastfeeding mothers reported confiding in their husbands when they were in conflict with their mother-in-law—for example, if they were still hungry and wanted to eat more or wanted a certain type of food that the mother-in-law was not approving. Thus, in many cases, the husbands were seen as the trusted member of the family, the last resource for the woman when/if in conflict with her mother-in-law. Many women reported that they could ask their husbands to buy some foods at the market if they needed something. In these situations, it seemed that the husband was the trusted partner, who ensured that his wife had what she wanted to eat. Some of them played a vital role by insisting that their wives took the IFA tablets and by ensuring that they were taken at the right time. Other husbands did not know about the importance of IFA. Regarding infant and young child feeding (IYCF), all of the four husbands interviewed reported very limited knowledge, and they felt that for their child to be healthy, it was better to give infant formula. One also reported that giving colostrum was not good for the child.

I really don’t know until what time my child should be breastfed. My wife had insufficient breast milk so immediately after birth we had to start Amul powdered milk as complementary food, and until now, we are continuing partly mother’s milk and partly Amul powdered milk. We did not give the colostrum. It was thrown out because we feel that the baby will not able to digest it and it will lead to loose motion of baby.

-IDI with father of children less than two years of age

My wife has never taken iron tablets during all the pregnancy times. I don’t know these tablets. I know that hot food should be served to the lactating mother after childbirth. Greens should be eaten. My wife had a lump in the breast so she could not give milk to baby in one breast.

-IDI with father of children less than two years of age

During pregnancy, my wife has taken all the iron tablets and other medicines as prescribed by the doctor. During her pregnancy, there were no restrictions on what she could eat...but after the child’s birth there is restriction of eating black eggplant and broiler chicken for six months, and fish for one month. My wife used to eat hot food till two to three months after childbirth.

-IDI with father of children less than two years of age

Within six months of childbirth, I gave gripe water to the child, and bonnison, and water apart from mother’s milk. My wife takes the decision on what the children will eat and whenever they go outside they carry some biscuits with them. No one in our village has ever given us some advice of what our children should eat. I am not sure what should be given to eat after six months...I don’t know. I believe they should be given everything to eat after six months, anything that is available within the house, but not sure when and what.

-IDI with father of children less than two years of age

After two months, we started formula food for the child as our relatives suggested us to do so. Our baby was weak so our relatives also suggested giving powders. Now our daughter is weak but I don’t have sufficient money to buy vitamins for her...My wife took a few iron tablets after I insisted; otherwise, she was not interested due to bad taste.

-IDI with father of children less than two years of age

All pregnant and lactating mothers interviewed were positive about the support they received from their husbands during the pregnancy. They shared that their husband tries to help them and also assures that they have access to the foods the women want to eat. Husbands were seen as trusted partners, although with limited influence regarding childrearing and maternal nutrition, as compared to mothers-in-law.

In our mother-in-law’s house, when we want to eat something we tell our husbands and they bring it from the market. If they bring the raw material in the morning, we cook and consume in the evening.

-FGD with pregnant women

My husband helps me if no one is there. He helps me in cooking and if I am ill, he helps me.

-IDI with pregnant woman

In addition to husbands, other family members, such as sisters-in-law, were reported as a source of advice and support.

I plan on only giving him my milk until he is six months old and then he will have rice and dhal. I don’t know how often to feed my child rice and dhal. I don’t know, but my sister-in-law will help me, she has children.

-IDI with mother with child less than six months old

3.2 Objective 2: Identify the Current MIYCN Practices and Barriers That Need to Be Addressed

3.2.1 Timely Initiation of Breastfeeding

Timely initiation of breastfeeding was found to be a common practice: most women (95 percent of lactating women) reported breastfeeding their child within one hour of birth. All women reported giving colostrum, although one man reported that his wife discarded the colostrum. Giving colostrum is now explained as being part of the traditions around birth. First, the new child is washed and massaged with turmeric, the mother is also cleaned, and then the baby is put to the breast. Many mothers reported that they knew they had to give the first milk, referred to as kasakheer. Most women reported giving the child colsotrum, but they did not know the importance of giving this first milk to the child, and it appears that this is not actually the decision of the mother, but rather something done by the birth attendant—the ASHA or mother-in-law. There is generally no prior explanation during pregnancy about the importance of feeding the newborn colostrum.

After the birth, definitely the child and mother are cleaned, then my child was put to my breast, I started breastfeeding within two minutes. I am not sure why I need to breastfeed immediately but I know I have to, I think it is required...It will keep the body warm for the child. It will give me stimulation for my breastfeeding. I know this by experience, after my first child. I give the first milk. It helps make the baby healthy; it always keeps the baby well. The child is well, everything goes well. I still only give breast milk. I know to give breast milk, when the child cries. I usually give breast milk every two or three hours. If the child cries, I immediately give her breast milk.

-IDI with mother with child less than six months old

After bathing the mother and child with turmeric powder and soap, I gave breast milk. After completing the bath, I gave my first milk—thin milk.

-IDI with mother with child less than six months old

When the baby was born, first they cleaned my child and me. Then they gave the baby to me to breastfeed. They keep it like this and I don’t know why...only feed the baby mother’s milk. I don’t know how often I feed my baby, I only breastfeed my baby, I don’t know how many times, but I breastfeed him whenever the baby is crying, I don’t count.

-IDI with mother with child less than six months old

3.2.2 Exclusive Breastfeeding up to Six Months

Although mothers and mothers-in-law reported that exclusive breastfeeding was the best food for the child, when probed, many of these same women reported that soon after birth, the newborn was introduced to other forms of foods and liquids, especially when neighbors came to visit, as this is part of tradition. Also, when the child is born during the hot season, there is a popular belief that the baby needs more water. If the baby is crying, this is seen as an indication for needing gripe water. Respondents widely shared that newborns and very young children were introduced to other liquids and foods early on. Several women reported being worried about the quantity of milk they were making and the inability to feed their children. A few reported thinking that their breast milk was causing the child to cry, because it was “bitter milk.” No woman reported knowing that a breastfeeding mother makes more milk as the child suckles.

Mothers breastfeed at first, and they give the colostrum. That is not the problem. Now women know to give the colostrum, but it is more about women giving other foods. Some women give honey, some women give water and sugar, and some women buy gripe water from the store. When the baby cries, they give the baby gripe water. Some women, in addition to the breast milk, give milk powder. They do both breast milk and milk powder. When the baby cries, the mother thinks the baby has not enough breast milk so she gives more food, she gives milk powder. Some mothers think they don’t make enough milk. Some mothers and caregivers (mothers-in-law) don’t know that the more the child breastfeeds the more milk the mother makes.

-KII with nutrition focal person of Panchayat

I am bottle feeding the baby from two months. No milk comes from my breast, from two months the milk decreased. My mother-in-law told me that I do not have sufficient milk. My mother-in-law advised me to start bottle feeding.

-FGD with breastfeeding mothers with children less than six months old

I think my milk is bitter, I don’t think my child likes my milk, I don’t think the child is drinking enough milk so I decided to give bottle feeding.

-FGD with breastfeeding mothers with children less than six months old

In addition, many respondents shared that although they knew about exclusive breastfeeding, they were not sure how often and how long the baby should be exclusively breastfed. Some mothers reported feeding the child when the child was crying; others reported feeding the child when the child was brought to them, while they are working in the field, as most women reported having to return to fieldwork after the first 21 days of rest. Many mothers reported leaving their child either in the home with an elderly caregiver (often the mother-in-law) or bringing the child to the field and leaving him/her by the edge of the field with a “minder.” Often, by the time the child is brought to them, the child is crying and hungry and has been soothed with biscuits. Some mothers reported introducing complementary foods around the fourth month, whereas mothers from some tribes reported that delaying introduction of complementary foods until after the ninth month was the tradition.

After 21 days, we can go back and work in the field. When I go to the field, I leave the child at home with the mother-in-law and the child is hungry until I come back home.

-FGD with mothers with child less than six months old

3.2.3 Continued Breastfeeding up to Two Years

Most mothers reported that they continue breastfeeding during the first two years, and some up to the third year.

The child will have the mother’s milk, what else will the child have? The small child will have the mother’s milk.

-FGD with mothers with children less than two years

A few breastfeeding mothers, although not giving formula, reported that they would prefer to give it. Many mothers reported that being able to give formula was associated with status and having enough money to feed one’s child well. Several women reported being influenced by their husband in choosing to introduce baby formula.

My husband gives importance to baby food for having a lovely child. My husband visits everywhere. He saw a picture of a healthy baby on the baby food packet. If my baby gets this food, my baby will be a lovely child, so my husband bought the food packet. I gave the food to the child, and I am also breastfeeding.

-FGD with mothers with children less than two years

3.2.4 Complementary Feeding

From the IDIs and FGDs with mothers-in-law, pregnant women, and breastfeeding mothers, it appears that families have very limited knowledge of when to introduce complementary foods. The practice varies from introduction of foods by the second month to past nine months. In addition, when asked what types of foods were first introduced to the child, all women reported “watery dhal and rice biscuits.” Based on these discussions, it appears that there are no special foods made for the child who is older than six months and less than two years old, other than the dhal that is usually eaten by the family, diluted for young children. There was no concept of introducing snacks and feeding the child more frequently than the meals consumed during the regular family mealtimes. All respondents shared that giving rice cakes to a crying child was common practice. Based on discussions with the UNICEF Regional Advisor and the ANMs, it appears that there is a critical need to focus on the appopriately timed introduction of complementary foods, as well as the consistency and frequency of feeds.

Complementary foods are critical to address; there is a lack of understanding of the need to diversify foods and there are so many inappropriate foods given, such as dhal kapani (watery dhal). Mothers are breastfeeding up to the fourth month in general, but they don’t know when to introduce complementary foods and what types to introduce.

-KII with UNICEF Regional Advisor, Keonjhar district

Introduction of Complementary Foods

Most women reported not being sure when to introduce complementary foods, and the practice varied across respondents. Some reported introducing “solids” (watery rice) by the second month, others by the fourth to fifth month, which seemed the most common practice. Many reported delaying the introduction of complementary foods until the seventh or eighth month. The common thread across all respondents was that women were unsure when to introduce new complementary foods and thus followed the advice of their mothers-in-law.

Before introducing any kind of food, I ask my mother-in-law what foods I can introduce. After eight months, I introduced foods. There was sufficient milk until eight months, and even now I still breastfeed.

-IDI with mother with child less than two years

My mother-in-law has told me to mix boiled rice with milk and sugar and give it to my child. This is good for my child. I give my child foods two to three times a day. I give it by myself. I don’t ask anybody. At seven months, my child started to have other foods than breast milk. I think I want to get Horlicks (a malt milk drink) for my child to make her strong.

-IDI with mother with child less than two years

Some families, in the scheduled tribes, don’t give foods to babies until the baby is one year old. Some families wait until the seventh month. This is tradition. In other families, members of the families eat the food given for the children from the Angwandi center. The child does not get the food, as the families are very poor and the adults eat the food.

-KII with ANM

Chatua and Other Foods Used as Complementary Foods

The GoI has put in place a scheme to provide food rations once a month to families below the poverty level. This food ration, known as chatua—a mixture of peas, green chickpeas, sugar, and peanuts—is calculated based on the number of family members and is targeted to pregnant women and children older than six months. There is often confusion, however, about when the chatua should be introduced to the child. Many respondents explained that the chatua is shared among family members, but also used as a complementary food. Some women explained that they give chatua only once a week to their child, while others give it daily.

We give chatua. We get two kilograms per month from the Anganwadi worker. We give it twice a day, two spoons mixed with water in the morning and in the evening. We increase the amount depending on what the child can take. We mix it with water or milk depending on what we have. We still continue with breast milk until three years old. In addition to this, we give kitchuri at noon, once a day. We mix vegetables, rice, dhal, papaya (cooked green papaya), potato, carrots, and beets. We mixd it and make kitchuri. We mix chura (flattened rice) with water and make rice cake and give in the morning and in the evening.

-FGD with mothers with children less than two years

I have introduced chatua after the seventh month. The chatua given by the Anganwadi worker gets finished in 15 days. I increase or decrease the quantity of chatua depending on what my child wants to eat. At eight o’clock in the morning, I give chatua to my child. Around 10 or 11 o’clock, I give Cerelac, and around two o’clock I give a regular lunch of rice, dhal, vegetables, or whatever is cooked for the family. At five o clock, I give another feed, and in-between I give breast milk. In the evening I give my child dinner—six to seven meals. I don’t give spicy food to my child. I give boiled foods to my child as spicy food will cause diarrhea. Sometimes instead of chatua, I give pita (the rice cake) and I make it soft by crumbling it to give to the child. Whenever I give rice with dhal to the child, I dilute it with liquid to make watery dhal.

-IDI with mother with child less than two years

Types of Foods, Consistency, and Frequency

Most women reported giving watery rice with dhal, sometimes giving only the cooking water of the dhal with salt. Many women reported giving chura—rice cake—as a morning and evening food. Mothers reported that they were aware of cold foods (foods associated with giving a child a cold) and hot foods. Fruits such as ripe bananas, papayas, mangos, and jackfruits were seen as cold foods and were not given to young children.

Children have their own food, and the food is on its own plate. There is no problem, the young child has its own bowl, but the problem is the food, it is very watery, mashed dhal, potato, rice, but not much dhal, very watery. The mother often mashes rice and potatoes, she also prepares rice cakes and that is what the child eats. Rice and potato, three or four times a day. But in very traditional families, most children eat only twice a day. Most women don’t give vegetables, only rice and potato or rice cake. Eggs are strictly prohibited. Eggs are not digestible. They are afraid their children will have diarrhea. No fish up to one year—the child cannot eat fish. The mother also does not eat fish for a year after she gives birth. Nobody takes ripe papaya, this is a cold food. We have many cold foods that cannot be given to the child or mother. If they eat cold foods, they will have a fever or a cold. For the first six month to a year, children only eat rice and dhal, after they start increasing other vegetables. Mothers continue to breast feed during two years.

-KII with Nutrition Focal Person of Panchayat

I plan to breastfeed for more than a year, not less than that. I plan on breastfeeding, it will continue and then I will give additional foods. This will start seven months onward. I will give rice, boiled potato, boiled papaya. We can give a little bit of eggs by the eighth or ninth month. We don’t give ripe papaya to the child, the baby will catch a cold. Dahl, rice, potato, and cooked papaya, that is what we know and that is what we give...I think the child needs to be fed three times when the child starts eating, that is what I think, three times a day.

-IDI with mother with child less than six months

After six months I gave some food, boiled vegetables, dhal water with small amount of rice to make it like a cream. I did not purchase packaged food, but I give papaya (cooked), eggplant, beans, and it is all mixed and mashed by hand. It’s hard to explain how much I give, a pinch full [she shows by holding her fingers together]. I give this six to seven times a day. At first, I often give her small quantities. Past one year, she can eat a little bit of egg, but I don’t give papaya not cooked or banana, because these foods give a cold to the baby. If we give some, we have to give in small quantities. My child eats everything. She even eats fish and chicken and sometimes liver and mutton.

-IDI with mother with child less than two years

Other Practices Related to Feeding

Feeding During Illness: Most, but not all mothers, reported continuing to breastfeed their children during illnesses. Many said that they stop giving all other foods, and reduce the amount of breast milk given, because they think that giving more food will lead to the child having more problems with digestion during the illness.

Mothers reported that it seems obvious to breastfeed the child when the child is ill, as this is a way to comfort the child. as most mothers continue to breastfeed for about two years, when the child is ill, they often see breastfeeding not only as a source of food but also as a source of comfort. When breastfeeding mothers are ill themselves, however, it appears that they stop breastfeeding, as they fear that the illness will come through the breast milk.

When the child is ill, the child prefers breast milk more than any other foods, but the amount reduces.

-IDI with mother with child less than two years

When she is ill, she likes to eat green leafy vegetables and soft rice, biscuits, and bread. If she has diarrhea, she likes rice and sagh (leaves).

-IDI with mother with child less than two years

When ill, mothers don’t go to the doctor, they prefer to go to the “quack.” Mothers stop breastfeeding when the child is sick. Mothers stop breastfeeding when they are sick as they think the illness goes with the milk.

-KII with nutrition focal person of Panchayat

Eating Out of Their Own Bowl and Hygiene

Children have an individual bowl, katori. If a bowl is not available, mothers reported using bowls made of banana leaves or putting the food on a leaf. Although very young children have a spoon, they are often fed by hand by the caregiver, and are soon encouraged to eat with their own hands. Although respondents explained that they knew that it was important to wash hands before eating, many reported that in their community “handwashing is a problem.”

Mothers reported knowing that to feed the child, they had to use clean water and would boil well water. However, although mothers reported cleaning their hands to prepare foods, or after defecation, when other key informants were interviewed, they highlighted the limited practice of handwashing as a key factor driving children’s diarrheal diseases in the community.

I have a separate bowl and spoon for my child. When I feed my child I don’t make it very thin or lumpy I just make it right. I don’t crush the food, I let the food be. (I don’t crush the rice.) I give water from the well but I boil it first. On average, I breastfeed my child five to six times a day.

-IDI with mother with child less than two years

3.3 Objective 3: Identify the Major Nutritional Issues Women Face, Including Societal Structures, Taboos, Barriers, and Promising Practices to Build Upon

3.3.1 Differences in Family Practices Due to Tribal Traditions and Socioeconomic Factors

It should be noted that this research was conducted in a small sample of rural villages in Keonjhar district, and thus the findings from this rapid assessment are reflective of the contextual realities of these villages in remote rural areas, with a predominance of ST inhabitants, a group of people who over centuries in India have been deprived of equitable access to education and health care. These findings are not specifically representative of India, but are representative of the contextual realities of the sampled villages. It is also important to understand that society is rapidly changing, as illustrated by the FGDs with pregnant women and other women who have had access to education. Despite the differences among tribes and within families, one recurring theme that came through strongly during the research was the limited agency of the pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers who live in the extended family context, where the mothers-in-law are still the major decision makers in the home.

Through this formative research, several factors affecting the lives of women and their children were identified. Families’ contextual realities vary within Keonjhar, due in part to the different tribal traditions, but also due to various other socioeconomic factors within individual families. Higher levels of education have been identified as a positive and protective factor for maternal and infant nutrition. In households where someone had attended school, respondents reported exclusively breastfeeding the child for the first six months and women reported facing fewer taboos. They also reported being well treated, eating enough, and having a chance to rest during the first six months of the life of the child.

The Munda (tribe) women have to work a lot, until they give birth and then they have to go back to work nine days after giving birth.

-FGD with mothers-in-law

In our community, there are a lot of women who give sugar, honey, and have pre-lacteal practices but for me, in my family, I am well taken care of because my family is well educated. My brothers have a good level of education and are working outside of the village. My father-in-law is a teacher, so he also knows what is good for the child and mother. All my family is making sure I can take care of myself.

-IDI with pregnant woman

Families are different—my family treats me well because of the level of education. It differs because of the level of education of family…My mother-in-law knows. Everyone in my family knows.

-IDI with mother of child less than two years old

3.3.2 Practices Are Changing: Fewer Food Taboos and Greater Understanding of the Need to Rest During Pregnancy and During the Postpartum Period

Change Might Not Be Happening Fast Enough for the Newer Generations

During the FGD with the mothers-in-law, the older women compared their lives during pregnancy and motherhood with the lives of their daughters-in-law, and reported that now, although there are still food restrictions, they are fewer in number, which generally don’t last more than six months, as compared to the one year that they had to endure.

You know, in our communities, some families restrict fish and chicken for daughters-in-law. There are still some food restrictions in limited families, but most people have started allowing them to eat foods, but there are still some restrictions. During our time, when we were pregnant, it was all restricted, but now it’s less. Before we had restrictions until the child was up to one year old. You should have seen how weak and tired the mothers were! But now, in most families, we don’t have these restrictions, but still some families have them.

-FGD with mothers-in-law

There are no traditional practices preventing the woman to eat anything during pregnancy. After the child is born, burnt things are given to the new mother. We give more of eggplant and garlic. We don’t give spicy food, sour foods, poi, and lady finger is not given. Earlier, when a child was born, mothers were given food and water only once, now the mother is given food three times a day.

-FGD Panchayat leaders

Greater Understanding of the Need to Rest during Pregnancy

The mothers-in-law reported that there is a better understanding of the need for pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers to rest: “This is a must for the child and women to remain healthy.” Mothers-in-law reported that, during pregnancy, to help their pregnant daughters-in-law, they themselves take on some of the daughter-in-law’s tasks, mostly the outside activities such as fetching water and cleaning the shed. After delivery, the new mother is expected to rest for the first 21 days, and the mother-in-law moves into her room to help with the child.

It was the practice for us to work until we deliver. It was to make us strong. But now it has been changed. Pregnant women should take rest—two hours a day, they should take rest…Sometimes we divide the work, we share the work with our daughters-in-law, and we give them relaxation. Our daughters-in-law share the work with us. We divide inside the house, the daughter-in-law after giving birth stays inside the house and does inside work, and we do the outside work. We clean the cow shed, we fetch water. Our daughter-in-law does the cooking, and serving of foods and clearing. Outdoor work we do. Rest is a must, but after lunch. She must take rest after lunch, even if someone comes to the house, then the mother-in-law must take care of the guests, she cannot be disturbed.

-FGD with mothers-in-law

However, it is interesting to note that during the FGD with pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers, many reported that they still faced a heavy workload during their pregnancy, such as fetching water and wood, cooking and serving meals, and cleaning the outside courtyard and cow shed. Many women described their daily tasks and the family expectations for them to continue to work until delivery, from a belief that this would make them strong.

Many mothers-in-law recommend us to work hard, so that the delivery will be easier. There is a chance of early delivery, sometimes the pain continues for a long time, so the pain period will be less if the pregnant woman works hard during pregnancy.

-FGD with pregnant women

One change that seems to be almost universal is that during the harvesting season, most pregnant women don’t go to the field in their last months of pregnancy, and don’t return to the field after the first month of giving birth (the first 21 days after birth). As illustrated by the discussions with the mothers-in-law and younger women, the concept of rest is understood, but the realities of workload put many demands on the pregnant woman and new mother. It is important to highlight that in many cases, the workload shifts to more fieldwork taken on by the mother-in-law or other sisters-in-law, husbands, or even parents of the woman, and the housework remains with the pregnant woman or new mother.

In terms of work, I have a lot of work. I clean the cow shed, the courtyard needs to be done with cow dung. My husband gives me some support by providing some help, but now everything is going on, this is the time of the harvest for the paddy...So my parents come to help my husband. My mother-in-law cannot help. I have a lot of housework. Three or four times a day I sweep the courtyard, I need to wash the house inside daily. Before being pregnant I was helping my husband with the paddy, but now I am not helping, I am working in the home. I go to the field to bring food to my husband.

-IDI with pregnant woman

Families as Supportive Entities

All women reported that within the families, there are a lot of supportive systems, where women share work, including responsibilities for caring for the new mother during the first 21 days after birth, and for the young child when the mother needs return to the field to work. Women are not isolated, as they have a built-in support system within their families, which includes mothers-in-law, sisters-in-law, and husbands when they return from fieldwork.

The First 21 Days Postpartum

After giving birth, the mother and newborn stay in one room, and the mother-in-law moves into this room to help care for both the new mother and baby. She is the primary contact with the outside world, as the new mother is not supposed to go out, and is not supposed to be touched by others. During this period, the mother-in-law decides what the new mother can eat, prepares her food, massages the new mother and newborn, and also decides, in most cases, if the child will be given gripe water, water, and/or honey. During this period, the mother-in-law is continuously there, providing advice and caring for the new mother and child.

After giving birth, I don’t go anywhere for 21 days, I have to stay inside the house. I don’t do any work for one month, I take rest. During the one-month period, I stay inside the house, maybe I do some small housework, but I do not do much for the first month. I rest. I have my mother-in-law and she takes care of the baby with me.

-IDI with mother

Going Back to Work and Childcare Practices

All women interviewed reported that after the first 21 days of rest, they had to get back to work, and “shoulder their responsibilities.” Childcare practices seem to differ greatly. Some mothers reported taking the child with them to the field while others reported leaving the child in the care of the mother-in-law. Mothers reported that the mother-in-law is in charge of taking care of the very young child, and if the child “cries too much” the child is brought to her when she is working in the field. The common thread of all these stories is that women after the first 21 days have to go back to work in the paddies (rice field). Many women reported being tired from having to go back to the field work right away, but really have no choice because the family needs their help.

We would like to look after our children and we think of their welfare, but our mother-in-law gives us a lot of work, then we are not able to take care of the children. We don’t have the time.

-FGD with mothers with children less than six months

3.3.3 Maternal Nutritional Practices During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Period

Enabling Factors

Good Understanding of the Need to Eat High-Quality Foods: Most women reported knowing that they “have to eat a balanced diet,” with different foods, but actually they shared that during their pregnancy, they eat the same food as the family eats, because the household lacks the income to buy diverse, higher-quality foods.

I know that I should eat eggs, milk, and fruits. Our in-laws suggest that we eat this, but it’s very difficult to afford. Whatever the family eats, I eat. I eat the same food as the family.

-FGD with pregnant women

Although there is a high awareness of the need to eat vegetables, eggs, fish, meat, and pulses, most women reported eating only dhal and rice, as this is what the family is able to purchase. Many pregnant women (80 percent) reported that their mothers-in-law believe that during pregnancy women should eat less to avoid having the fetus growing too big, which would lead to complications during delivery. However, as described above, some beliefs and traditions are changing. Many younger pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers reported that although their mothers-in-law advise them about the type of foods to eat and the quantity, these younger women also receive advice from the ANM and ASHA and are therefore becoming more empowered to make their own, informed choices.

Our mothers-in-law suggest to eat less so that the baby will not grow so big...We believe we should eat less times but more quantity, when we are hungry. But our mothers-in-law suggest to eat less...but that does not happen, we feel hungry and so we eat as much as we want. Now we eat more times and more food.

-FGD with pregnant women

Other pregnant women reported knowing that “good food is necessary during pregnancy,” but were unclear for which reasons and stated that food would help them to deal with the pains of giving birth and also would ensure that their newborn was healthy. Although the information might be limited, most pregnant women could explain that eating higher-quality foods during pregnancy would help them and their child.

Good food is required. It lessens the pains when we give birth. I will have the stamina to give birth and I will have the stamina to register for the pains. There might be many other things that I don’t know much, but I think the child will be in good health also.

-IDI with pregnant women

Barriers Affecting Optimal Maternal Nutrition

Gender Role within the Family: Pregnant women also reported instances of “going to bed hungry” once or twice a week, especially if there were guests, or if food ran short. Almost all of them ate only after they had fed the other family members, including their children, husbands, mother- and father-in-laws, brother- and sister-in-laws. The women also reported that mealtimes were likely to change based on the amount of housework. The first meal of the day was reported at 10 or 11 AM, while the next meal was around 4 or 5 PM. Pregnant women started their day at around 5–5:30 AM.

Food Taboos: Food taboos were reported mostly during the postpartum care period, for the first six months of life of the new child. As mentioned previously, the food taboos are changing as mothers-in-law reported that “during their time, there were food taboos until the child walked, for the first year of the child.” Many of the food taboos are linked to the quantity of foods a breastfeeding mother can consume. Many breastfeeding mothers reported that their mothers-in-law advised them not to eat too much, because if they did, the newborn child would face an increasing risk of not being able to digest the breast milk. In most communities, women reported eating only rice, kulthi dhal, and burnt brinjal (eggplant) during the first 21-day period. Most women reported having only two meals a day, while some reported eating only once a day. Drinking water was also restricted to the same number of times.

My mother-in-law said that the mother should take rice twice per day for up to three months after giving birth, and after three months she should take rice more than three times. At the beginning, she needs to take two meals a day…My mother-in-law told me to take two meals a day because the baby eats small amounts, the baby is small, when the baby grows a bit more, then my mother-in-law said I can eat more times, three times a day.

-FGD with pregnant women

Up to 21 days, we are given garlic, boiled eggplant, khulti dhal, mashed potato to eat, and that’s it. We have meals at two times, once at 10 AM and once around 21 to 22 hours in the evening. Our in-laws have asked us to stop eating more times because the child will not be able to digest…During this period, I can only drink water twice a day. We don’t have biscuits or any other thing. We feel tired and weak.

-FGD with breastfeeding women

My mother-in-law tells me the child will get sick if I eat different foods. If I eat more, the mother cannot digest the food and the child will have digestive problems. I believe my mother-in-law. I won’t be able to digest the food, I believe my mother-in-law, she knows. I will tell my children this later when I am a mother-in-law. I eat different foods than the rest of the family. I can only eat boiled rice, pumpkin, potatoes, but I am not feeling hungry, I am okay. I am not sure how long I will have to eat these different foods. My mother-in-law did not tell me yet, so I don’t know. Everyone else in my family is eating different foods, some kind of spinach, sometimes also chicken, sometimes eggs also, but me, I eat different foods and I don’t know for how long.

-IDI with mother with child less than six months

There are other taboo foods, with many classified as hot or cold foods (which may be based on or attributed to ayurvedic principles). These taboos are quite specific to the different tribes and families. Some foods are believed to help the breastfeeding mother produce more milk, such as the bitter gourd and brinjal (eggplant); other foods are believed to be “cold foods,” such as ripe papaya and pineapple, which if consumed by the mother, will cause the child to become sick. Some foods, such as eggs, are totally prohibited by some tribes. Since the taboos vary according to tribe, clearly understanding the contextual realities of the villages is necessary.