Just outside Jalalabad City in the town of Kok-Jangak, the future of the Kyrgyz Republic is getting its start at Raduga Kindergarten. But like many Kyrgyz children, these students are at risk of stunting, or short height-for-age, an indicator of malnutrition that can have lifelong physical and cognitive impacts. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), through its multi-sectoral nutrition project—Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING)—is empowering community volunteers to improve nutrition among women and children.

I only have a small budget of 770 soms ($11.16, a combination of government and caregiver contributions) per child each month, but I do my best to ensure the children are receiving a diverse diet.

-Elmira Alikeyenva, Director of Raduga Kindergarten and SPRING Activist

Led by Elmira Alikeyeva, Raduga Kindergarten serves close to 90 students between 2-6 years of age. Many come from military or migrant families, which means that they are often cared for by grandparents while their parents work in other parts of the country or abroad.

Elmira became a SPRING community volunteer (or activist) after hearing about SPRING’s work to improve nutrition at a community meeting in Kok-Jangak. As an activist, she receives bimonthly trainings on nutrition and hygiene and uses SPRING’s nutrition education materials when visiting homes in her community, holding community meetings, and encouraging improved nutrition practices at her school. Every three months, Elmira organizes seminars for the parents and caregivers of her students on improving dietary diversity and handwashing, and the prevention and treatment of helminth infections.

Going Above and Beyond

The kindergarten serves the children breakfast, lunch, and snacks daily, making it an ideal place to learn about and practice good nutrition and hygiene. Elmira worked with the kindergarten’s cook to incorporate recipes from a cookbook developed by SPRING that draws on locally available food to improve the nutrient content of traditional Kyrgyz recipes. For example, with the addition of lentils and kidney beans to the recipe for mash cordo, a popular local soup, the meal gains protein, vitamins, and minerals. The soup is affectionately called raduga or rainbow soup and has become the students’ favorite dish. Other favorite recipes include pumpkin porridge, carrot salad, and beet salad with walnuts.

Elmira acknowledges that changing behavior is hard, especially when it comes to dietary diversity. “The traditional Kyrgyz diet isn’t very diverse. People eat the same things – especially meat and starches – every day.” But despite the challenges, Elmira is committed to changing norms to improve the health of her community, drawing inspiration from the small changes she sees daily in the kindergarten and the households she works with.

Children at the school now routinely wash their hands with soap and water before eating and after using the toilet. Elmira reported that a recent medical review by health providers demonstrated that these small changes can have big impacts: Raduga Kindergarten reported fewer cases of anemia and infectious diseases than in the past.

Motivated Volunteers

Motivated volunteers like Elmira have helped to extend SPRING’s nutrition and hygiene messages beyond the target 1,000-day households – those with a pregnant mother or child under two years. By using Raduga Kindergarten as a platform, she is helping children not only learn healthy habits early in life but also share them with their parents, grandparents, and siblings at home.

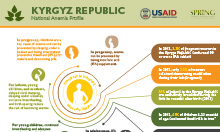

SPRING works to improve the nutritional status of women and children in the Kyrgyz Republic by improving nutrition-related behaviors, enhancing the quality and diversity of diets, and supporting evidence-based nutrition policies. By mobilizing and training activists like Elmira, SPRING is able to reach households with key nutrition and hygiene messages through household visits and community meetings. Each month, approximately 2,600 community activists reach more than 21,000 caregivers and more than 7,500 children under two from about 4,000 households throughout Jalalabad and Naryn oblasts.