A Recipe for Policymakers, Planners, and Program Managers

Introduction

Poor nutrition is one of the most important challenges to the development and growth of nations and communities. In its recent Global Nutrition Coordination Plan 2016–2021, the U.S. Government committed to “improving nutrition throughout the world in order to enhance health, productivity, and human potential” (USAID 2016).

There is broad agreement that nutrition is a multi-sectoral problem, yet nutrition-related services are often still delivered in sector-specific silos. Recognizing the many factors affecting nutrition, countries around the world have developed multi-sectoral strategies, policies, and plans for addressing malnutrition. Translating such policies into action at the community level will require a capable workforce from across a range of disciplines. However, not enough has been done to engage, empower, coordinate, or support all of the community workers who do—or could—impact nutrition, growth, and development.

The SPRING project is committed to creating an environment where nutrition, growth, and development is possible. We believe that program designers, planners, and implementers must work together with a range of stakeholders to create a shared vision of what is needed, who will do it, and how. Throughout this document, we have envisioned this harmonized approach as a “recipe” for good nutrition, growth and development, with community workers responsible for making sure all the “ingredients” are available to families and communities.

Who Should Use This Recipe

SPRING developed this recipe—including the guidance, graphics, and other resources—for government and nongovernmental program designers, planners, and implementers, state- or district-level food and nutrition committees, nutrition secretariats, or other nutrition champions charged with working multi-sectorally.

Why Use This Recipe

There are typically many resources, organizations, and activities at the community level that touch upon, enable, constrain, or profoundly impact family nutrition. By using this recipe through a facilitated process, a picture emerges for the whole of the community about how those resources and activities can be aligned for better nutrition and all that it can foster. Engaging in the recipe process means that stakeholders will be encouraged to think beyond their narrow niche or focus area and to develop together a shared vision for good nutrition, growth, and development in the community. This shared vision can then guide efforts to strengthen systems and design programs.

How to Use This Recipe

We recommend the following tips for using this recipe:

- Identify actors who have the power to convene key stakeholders and skilled facilitators to guide the process.

- Cast a wide net to engage those involved in designing, implementing, monitoring, and managing community-based nutrition-related interventions that aim to improve food security, household resources, resilience, care practices, and/or health services, including those for water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH). It is critical that the right participants are in the room for the workshop.

- Remember to leverage what is available, including human resources. Communities have many resources already.

- Think beyond activities that directly improve nutritional status to include those that indirectly support good nutrition or, at the very least, “do no harm.”

- Give community members a voice in designing and implementing nutrition interventions adapted to community needs and limitations, including those related to gender bias and wealth dynamics. This will build ownership and ensure mutual accountability.

You can use the resources in this recipe during one 2-day workshop or in a series of workshops or meetings, each tackling a different topic and undertaking different activities. Additional suggestions on how to use each resource are provided in the sections that follow.

Regardless of how the resources are used and who is invited, a skilled facilitator who is familiar with community-based nutrition activities should help guide discussions. Using these resources in a workshop context will take a number of days and may require adapting the resource to the local context and group of participants.

When to Use This Recipe

SPRING recommends using this recipe during planning and program design; however, the process might also be useful as part of iterative annual work planning to reassess and modify interventions or as part of a district assessment to strengthen coordination of human resources during planning and budgeting.

Regardless of when you use the recipe and plan the workshops, they will be most productive after an initial context assessment has been completed. In addition, if participants have a basic understanding of key concepts related to nutrition in the community, they are more likely to benefit from a recipe workshop. Tools such as SPRING’s Workforce Mapping Tool can be useful for assessing the context and SPRING’s Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture Training Resource Package includes presentations and other resources for an orientation to the importance of nutrition to growth and development.

Identifying the Ingredients for Good Nutrition, Growth, and Development in the Community

Figure 1: Ingredients Families Need for Good Nutrition, Growth, and Development

To design a program for improving nutrition at the community level, program designers, planners, and implementers need to determine the context-specific determinants of nutritional status.

Session guidance: Workshop facilitators will print and distribute handout 1 (see annex 3) to all participants or and/or print and display it as a poster, then explain and discuss each ingredient and its relationship with nutrition. Facilitators will then ask participants to divide into small groups – one for each ingredient – and describe, based on available evidence and their own knowledge of the target “community,” the availability of each “ingredient” and its accessibility to all families and family members in the community.

Background: The recipe for good nutrition, growth, and development calls for a number of evidence-based ingredients (figure 1) that families will need. This recipe provides a simple way to think about and discuss multi-sectoral nutrition at the community level and includes:

Box 1: Priority and Essential Nutrition Actions (UNICEF 2013; WHO 2013; Bhutta et al 2013)

- Consuming multiple micronutrient supplements during pregnancy

- Consuming iron and iron-folate supplements during pregnancy

- Consuming vitamin A supplements and/or during pregnancy

- Consuming calcium supplements during pregnancy

- Initiating breastfeeding within the first hour after birth

- Breastfeeding exclusively for six months

- Continuing to breastfeed for up to two years

- Introducing safe and nutritious solid, semi-solid, or soft foods in addition to breastfeeding at about six months of age

- Feeding children micronutrient supplements

- Feeding children a diverse diet

- Feeding children with age-appropriate frequency

- Feeding iron-rich or iron-fortified foods to children 6 and 59 months of age

- Providing vitamin A supplements to children 6 and 59 months of age

- Providing preventive zinc supplements to children 12 and 59 months of age

- Consuming iodized salt

In addition, water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) practices as well as delayed pregnancy, birth spacing, deworming, and malaria treatment have often been included in this list.

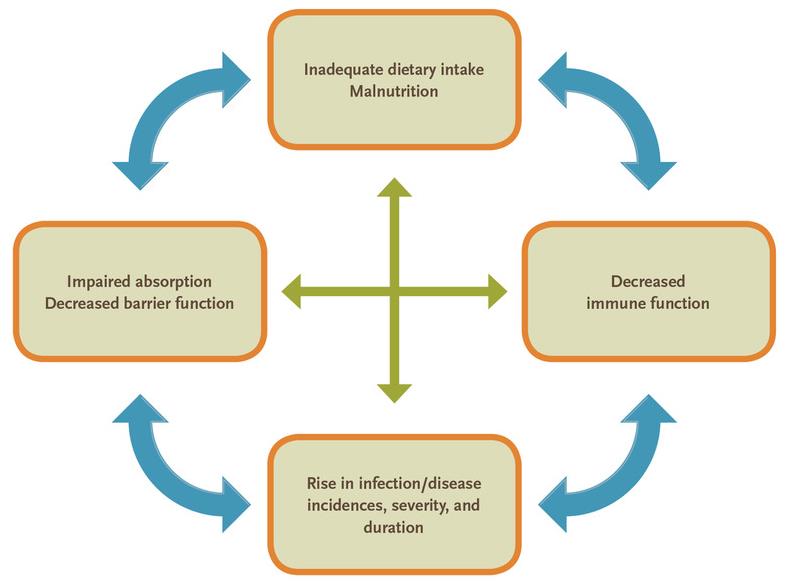

Figure 2: Links between Nutrition and Health

- Food: Food, including supplements and fortified foods, must be accessible and sufficient, safe, nutritious, and varied to support a healthy, active life. It must be free from contaminants that might cause illness, available year-round, and at a price people can afford.

- Caring practices: Improving nutrition requires the sustained adoption of optimal caring practices or behaviors (see box 1). Many of these are practices that women must adopt or are commonly viewed as the responsibility of women. However, it is important that the family (including men) support the sustained adoption of these practices.

- Health services: Health and nutrition are inextricably linked (see figure 2). All but a few of the priority nutrition interventions (see box 1) are provided by the health system (Bhutta, et al. 2013). Good nutrition requires access to quality health services, such as services to prevent disease, monitor growth, treat malnutrition, and support the adoption of caring practices.

- A clean environment: A clean environment means children drink safe water and learn good handwashing habits; latrines are available, safe, and clean; household and institutional waste is appropriately disposed of, and human and animal feces are kept away from children. Creating and maintaining a healthy environment requires infrastructure, equipment, and supplies, such as latrines, food storage facilities, supply, and water storage facilities.

- Income: Consistent and reliable income is needed to pay for nutritious food, water treatment, sanitation products and equipment, hygiene products, and health care. Household income may include loans and remittances. Evidence shows that additional income—from programs such as conditional cash transfers—can lead to positive effects on dietary diversity and stunting, as well as several intermediary outcomes, including greater food expenditures and higher quality of diet (Leroy, Ruel and Verhofstadt 2009). However, income generation does not always have a positive effect on nutrition (World Bank 2007). Households—ideally both men and women—will need to make nutrition-sensitive decisions regarding household savings and expenditures.

- Empowered women and engaged men: Evidence shows that when women have equal access to, and control over, household resources and income, agricultural outcomes improve, investments in education and health care for children increase, household food security is strengthened, and children’s nutrition improves (Mukidi and Oniang'o 2002; USAID 2014b). However, activities intended to improve women’s income or empowerment can sometimes have adverse effects on nutrition, such as adding to women’s already heavy workload, requiring strenuous labor during pregnancy, or leaving them with less time for infants and young children (SPRING 2014). While there is limited research on the impact of men’s support for maternal and child health outcomes, the available evidence suggests that engaging men can lead to improvements in spousal communication and support, more equitable treatment of children, and greater utilization of health services for men, their partners, and their children (Biratu and Lindstrom 2006; Danforth, et al. 2009; Mumtaz and Salway 2007; WHO 2007).

- Education: Through education, children, women, and men build the skills needed to make positive decisions concerning education, food, health, WASH, and care—and act on them. Education can, “through general improvements in literacy and specific health studies, increase desired and actual use of health services” (Ensor and Cooper 2004). Education can empower adolescent girls and women, giving them confidence and the capacity to adopt optimal care practices. It can encourage men to stay engaged in their wives’ pregnancies and their children’s care. Educated mothers and fathers are more likely to understand health and nutrition messages and to have the authority within their families to act on those messages and directions. In addition, according to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, nutrition education is “a key element in promoting sustainable healthy eating behaviours and should start from early stages of life” (Rao et al. 2006).

Creating a Shared Vision for Good Nutrition, Growth, and Development in the Community

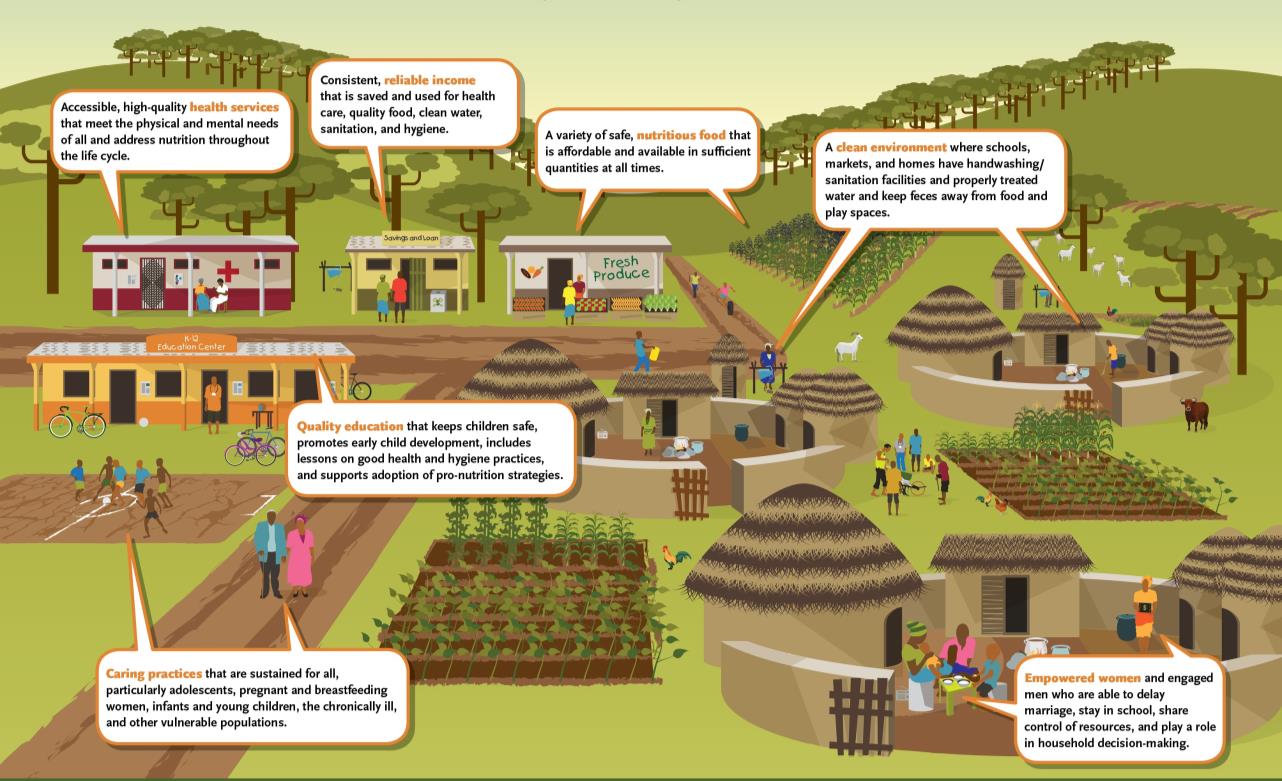

Having a shared vision of a community with the ingredients for good nutrition, growth, and development (figure 3) can help to motivate workers and to coordinate their efforts.

Session guidance: Workshop facilitators ask participants to work in small groups to draw their own community, paying particular attention to the ingredients that are or are not available. Facilitators can distribute handout 2 (annex 3) to all participants, as needed, as an example. Once participants are done with their initial drawing, facilitators will ask them to add to their drawings any additional ingredients needed, thereby creating a realistic shared vision.

Background: The illustration in figure 3 depicts an ideal community that has all of the ingredients for good nutrition, growth, and development.

Figure 3: Nutrition, Growth, and Development in the Community

Identifying the Community Workers Who Can Help Families Collect the Ingredients

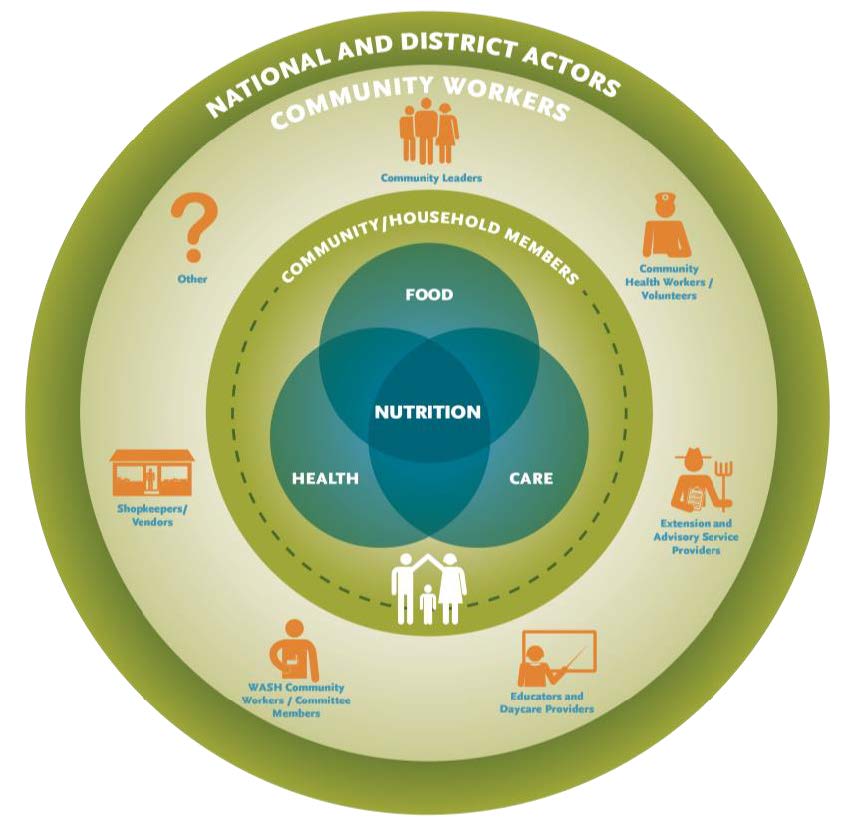

In addition to determining the availability and accessibility of ingredients for good nutrition, growth, and development, program designers, planners, and implementers need to identify the workers who can help families collect the ingredients. They will need to think beyond the health worker, who often is seen as the sole provider of nutrition services, to include a wider range of workers operating in each community (figure 4), and determine their current and potential nutrition-related roles and responsibilities.

Session guidance: During this session, workshop facilitators will build on their shared vision of a community with the ingredients for nutrition and their knowledge of the community in order to identify the community workers who can help families collect the ingredients and determine how they can do so. They will present figure 4 and discuss the types of workers that might work or volunteer in their community.

Figure 4: Community Workers Who Can Help Families Collect the Ingredients

Workshop facilitators will then distribute worksheet 1 (annex 3). They will ask participants, once again working in groups, to identify those who work or volunteer at the community level and how often they are actually in the community. Participants will record the cadres or titles of these workers, volunteers, or other actors in the “community workers” ring of the graphic. Workshop facilitators will need to explain that this should include those who work with the public and private sector and those who do not reside in the community, but regularly—even if rarely—visit the community.

Then, working in sector-specific groups, participants will discuss how workers in their sector could help families collect the recipe ingredients—what could they grow, sell, provide, promote, support, or model to improve nutrition in their communities? If participants are unsure of what workers in their sector could do to help collect certain ingredients, workshop facilitators can distribute handout 3 (annex 3), which is a list, organized by ingredient, of some of the activities that can be done to help families collect each ingredient. Participants will record their ideas in the first three columns of worksheet 2 (annex 3).

Note: The activities in this list were deliberately organized by ingredient rather than by type of community worker. This is partly because the roles and responsibilities of each type of worker can vary significantly from context to context, but also because responsibilities often overlap across different categories of workers.

Background: While there is global consensus on priority interventions for improving maternal and child nutrition, and countries are beginning to show progress in scaling up proven nutrition interventions, the responsibility for those interventions often falls on a select few. As described in USAID’s paper on local systems, “achieving and sustaining any development outcome depends on the contributions of multiple and interconnected actors. Building the capacity of a single actor or strengthening a single relationship is insufficient. Rather, the focus must be on the system as a whole: the actors, their interrelationships and the incentives that guide them” (USAID 2014a). Indeed, a wide range of community workers—many of whom are not traditionally considered part of the nutrition workforce—play a role in collecting the ingredients by growing or selling food; providing services; promoting or modeling practices; and ultimately supporting nutrition, growth, and development (figure 4).

These workers might affect nutrition directly or indirectly. It could be through providing food supplements, counselling women on breastfeeding, helping farmers grow nutrient-rich crops, vaccinating chickens, teaching adolescent girls and boys how to balance a household budget, modeling optimal behaviors, or simply not doing certain things that might negatively affect nutrition. For a list of some of the many activities that workers may conduct that contribute to nutrition see handout 3 in annex 3. In addition, more than one worker may be responsible for the same task or tasks.

The community workers who will likely be involved in collecting the ingredients for nutrition will vary from community to community or at least from region to region. Who they are will also depend on government structures, implementing agencies, and development programs. However, they will most likely include at least one cadre of worker in each of the following categories: community leaders (members of community groups, religious leaders, traditional leaders, and local government officials), community health workers and volunteers, teachers and daycare providers, extension and advisory service providers, WASH workers or committee members, and shopkeepers and vendors. What follows are descriptions of some, but not all, of these community workers.

We will strive increasingly to quicken the public sense of public duty; that thus . . . we will transmit this city not only not less, but greater, better, and more beautiful than it was transmitted to us.

-Oath of office required of council members in ancient Athens

Box 2: Reasons Why Schools Are an Ideal Setting for Promoting Healthy Eating

- “They reach most children, for a number of years, on a regular basis.

- They have a mandate to guide young people towards maturity. Given the vital role of nutrition in a healthy fulfilled life, nutrition education is part of this responsibility.

- They have qualified personnel to teach and guide.

- They reach children at a critical age when eating habits and attitudes are being established.

- They provide opportunities to practice healthy eating and food safety in school feeding programmes, and through the sale of food on their premises.

- They can establish school policies and practices – for example, sanitation facilities, rules about handwashing – that can improve health and nutrition.

- They spread the effect by involving families in their children’s nutrition education.

- They can be a channel for community participation, for example via school garden projects or school canteens, or through local intersectoral committees.

- They can provide cost-effective nutrition interventions (other than education).”

Box 3: Country Examples of Engaging Community Workers in Nutrition

SPRING/Ghana

In fifteen districts in northern Ghana, SPRING used an advocacy video on nutrition and stunting, “When a King has Good Counselors his Reign is Peaceful,” and a community-based quality improvement approach to engage local leaders, youth groups, water committees, and women’s groups to discuss priorities and develop action plans. SPRING’s multi-sectoral 1,000-Day Household Approach engaged health, education, environment, agriculture, and community development workers in improving the nutrition of pregnant women and children 2 years of age and younger.

Suaahara II / Nepal

As part of its Multi‐Sectoral Nutrition Plan, the Government of Nepal designed decentralized structures at all levels for multi-sectoral coordination and engagement. The USAID-funded Suaahara II project is working with those structures at the community level to help ward citizen groups conduct monthly multi-sectoral meetings and create a shared vision of a well-nourished household.

- Community leaders: Members of community organizations, including women’s groups, mother’s groups, religious entities, farmers’ cooperatives, school boards, parent-teacher associations, and local health committees support many of the basic ingredients needed for good nutrition, such as income generation, quality service delivery, behavior change. Local leaders, such as traditional leaders, religious leaders, local development committees, and elected government representatives, also play an important role in supporting and ensuring the delivery of nutrition-related services. These groups and individuals can exert substantial pressure on communities, and often make decisions regarding how government or local resources are used, or who benefits from development programs.

- Community health workers and volunteers: There are many types of community health workers (CHWs), recruited in different ways, with widely different training and assigned tasks, working or volunteering in the public and non-governmental sector, with and without compensation and incentive schemes. Some are paid staff, but the majority are volunteers or are given small incentives to do assigned work; some work at primary health care (PHC) facilities, others live and work in communities and visit families and women and children in their homes.

- Educators, including teachers and school administrators, exist in almost all communities. Daycare providers or early childhood educators, including informal childcare providers, are less common than teachers in these communities, since family members (including older siblings) often care for children. Where they do exist, they are usually unsupported and/or untrained. All of these education workers play an important role in helping to form and change behaviors to improve sustainable nutrition and health practices among children, adolescents, and adults (see box 2).

- Extension and advisory workers: Extension and advisory services exist in many countries to support farming practices, livestock rearing, and/or other income generation endeavors, but vary widely in their roles and responsibilities and their “reach” into communities. When active, extension and advisory service providers have “direct and sometimes extensive links to farming communities in rural and remote areas. These links are founded upon well-established structures and systems that cover most farming households” (Fanzo 2015). Regular contact with community members, particularly farmers, means that these service providers have established relationships within communities and good awareness of social norms and beliefs, as well as challenges and opportunities (Kuyper and Schneider 2016). Often focused on livestock, agricultural production, and income generation, they typically promote good agricultural practices during planning, planting, managing, harvesting, storing, preserving, processing, selling, and distributing.

- WASH committee members: Responsibilities for water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) often cut across ministries, with some holding responsibilities for infrastructure (e.g., ministries of public works, education, water, environment) and others holding responsibility for promotion and use of WASH facilities/services (e.g., ministries of health and education). While the latter may have staff at the community level, infrastructure activities are primarily managed at the district or sub-district level and often do not include community-based workers. This paper’s focus is on those who work at the community level from private companies and organizations, as well as community WASH committee members and community members themselves who take the lead in constructing latrines and maintaining water systems (Zakiya and Uwejamomere 2016).

- Shopkeepers/vendors: Shopkeepers and vendors provide critical inputs for nutrition and can be quite influential in the community at promoting, triggering, or facilitating behavior change based on their products and prices. Different types of vendors sell a range of nutrition-related products and agricultural inputs, such as food, seeds, and medicine, as well as irrigation tubing, supplies for construction of latrines and handwashing stations, soap, and other cleaning supplies. They can sell products that promote healthy behaviors, but can also create barriers or hinder improvements in nutritional status. Shopkeepers engage with larger retailers or wholesalers who can be influenced by nationally-set subsidies, tariffs, and taxes. It is in their interest to build trust with their customers to make a profit and sustain or grow their business. Aligning nutrition- sensitive actions with those incentives is a good practice for partnering with shopkeepers.

- Other workers: This list is not exhaustive and some communities may have other workers who do not fall into any of these categories. For example, micro-finance schemes sometimes have a strong presence in communities.

Examples of how community workers from multiple sectors have been engaged and mobilized for nutrition in Ghana and Nepal are presented in box 3 and in more detail in annex 1.

Supporting the Community Workers Who Can Help Families Collect the Ingredients

For community workers to bring about change in nutrition they need support. In some cases, support systems may already exist. In other cases, efforts will be required to clarify roles, train, provide resources, regulate, motivate, supervise, and support.

Figure 5: Factors Affecting Worker Performance

- Clear expectations

- Competence

- Timely feedback

- Incentives and motivation

- Adequate environment

Session guidance: During this session, the workshop facilitator asks participants to consider what they know of the support and regulatory systems that affect each worker and then to begin planning efforts to address the gaps. This may be tackled sector by sector and may benefit from the participation of the workers themselves. Participants record their conclusions in the final five columns of worksheet 2 (annex 3). It is important to keep in mind that this is only the first step in a long process of strengthening systems to better support community workers.

Background: Worker performance is affected by many things. These are often grouped into five distinct factors: clarity and shared understanding of roles, responsibilities, and expectations; competence; the provision of timely feedback; incentives or some intrinsic motivation; and the environment, including the availability of supplies and infrastructure (figure 5).

Having clear expectations of these roles and responsibilities—agreed upon or understood by all key stakeholders—can result in stronger relationships, better coordination, greater legitimacy and trust within the community, increased demand for services or products, increased linkages between nutrition-related roles and responsibilities and individual goals and objectives, and improved worker motivation.

Managers, supervisors, community workers, and community members need to agree on workers’ nutrition-related activities. Handout 3 in annex 3 contains a list of some of the nutrition-related activities that community workers may conduct. In each country or context, community workers’ roles and the activities for which they are responsible will vary. It is important to recognize that, in many cases, more than one worker might—and possibly should—play similar roles or undertake the same activities. For example, community health workers, WASH committee members, and teachers can all promote better sanitation and hygiene practices. In addition, since job descriptions do not exist for all community workers, such as vendors and distributors, facilitated discussions with district officials and/or community members and leaders will be particularly important.

Box 4: What is competence?

The term competence is often misused to refer to a specific skill area, such as communication or decision making, when it is actually a training approach that ensures that workers are competent to perform certain tasks.

- A skill (technical, communication, and decision-making) is about doing something well—your ability to choose and perform the right technique at the right time. It’s usually developed through training and practice.

- Technical knowledge (theory or technical content) is knowledge gained in a specific topic or expertise.

- An attribute is an inherent characteristic or quality and is often expressed through what you think, do, and feel. Among community workers, attributes can lead to trust, respect, and adherence to advice from community members.

However, a shared understanding of each community worker’s nutrition-related roles and responsibilities is only the first step.

In addition, to ensure that workers are competent (see box 4), they will need to understand their nutrition-related responsibilities and have the necessary knowledge, skills, and attributes to carry them out. Their competence will need to be built during pre-service and/or in-service trainings and reinforced during follow-up conversations, mentoring mechanisms, and/or supervisory visits.

Motivating a wide range of workers —including those with little interest or stake in nutrition—to take steps toward improving nutrition means helping them understand why such changes are important. They may need incentives such as remuneration—in cash or in kind (e.g., food, services, goods), but they may also be incentivized by demand for their services, respect, and recognition. Finally, to be able to carry out their roles and responsibilities, they will need adequate infrastructure, equipment, and supplies. Additional guidance and resources for addressing these performance factors can be found in SPRING’s guide, Raising the Status and Quality of Nutrition Services (2017) and in annex 2.

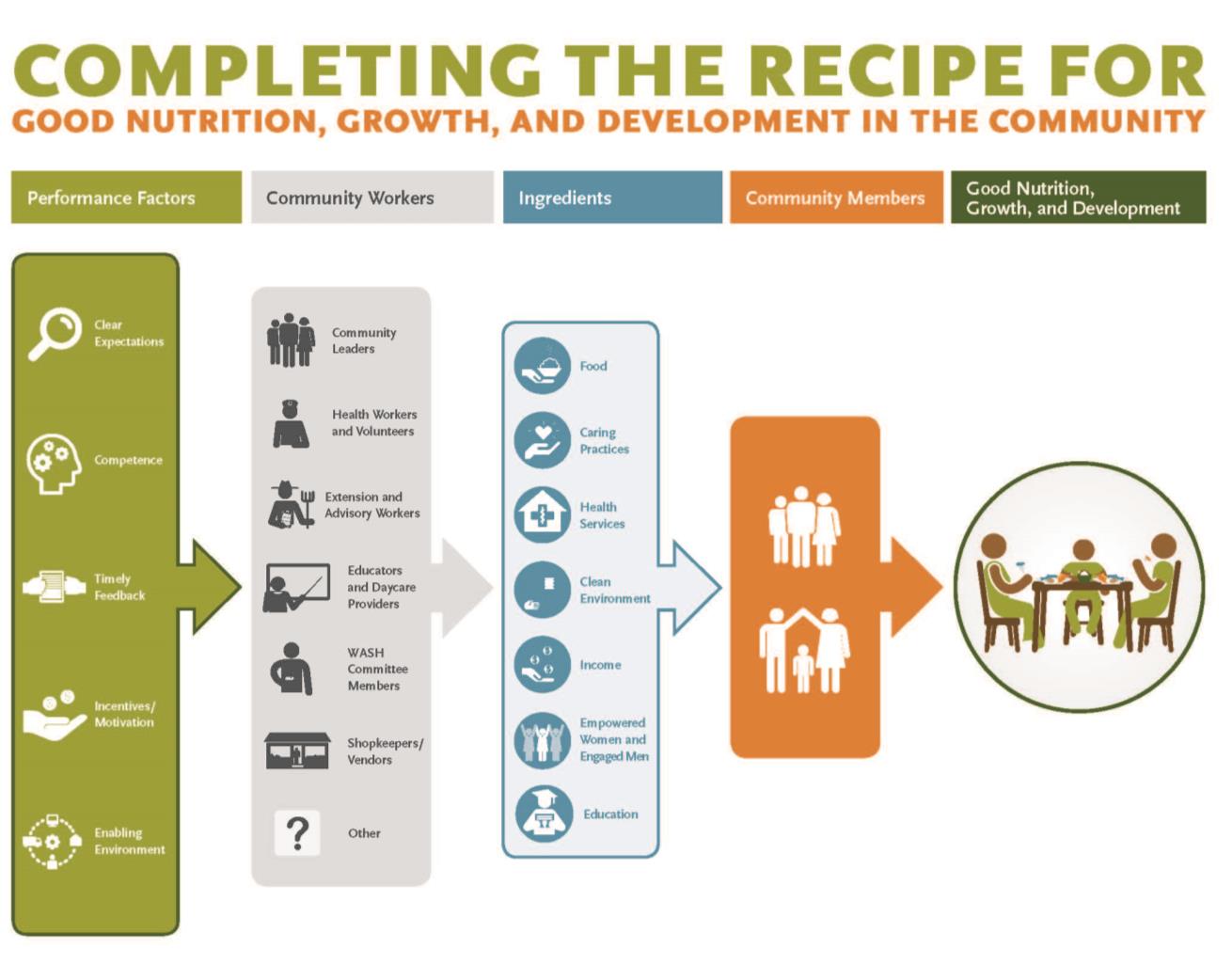

Completing the Recipe for Good Nutrition, Growth, and Development in the Community

In this document, we have presented our vision for good nutrition, growth, and development in the community, suggested some of the community workers who will need to be involved, and highlighted what workers need to effectively promote, support, and model nutrition in a coordinated and efficient manner.

We have included guidance on how to engage a multi-sectoral group of stakeholders in developing a shared vision, identifying the workers, and prioritizing next steps to support those workers. We have also included handouts and worksheets that we hope will be useful and adaptable for particular contexts and objectives. Figure 6 pulls it all together: the recipe is successful when a variety of community workers, with the right supportive performance factors in place and with access to the right local ingredients, remain accountable to community members as they work with each other toward a shared vision of good nutrition, growth, and development.

Figure 6: Completing the Recipe for Good Nutrition, Growth, and Development in the Community

To view the annex, please download the full report above.

References

Bhutta, Zulfiqar A., Robert E. Black, Parul Christian, Majid Ezzati, Sally Grantham-Mcgregor, Joanne Katz, Reynaldo Martorell, Mercedes De Onis, Ricardo Uauy, Cesar G. Victora, and Susan P. Walker. 2013. "Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries." The Lancet 382(9890): 427–51. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60937-x.

Biratu, B. T., and D. P. Lindstrom. 2006. “The influence of husbands’ approval on women’s use of prenatal care: Results from Yirgalem and Jimma towns, south west Ethiopia.” Ethiopian Journal of Health Development, 20(2): 84–92.

Danforth, E. J., M. E. Kruk, P. C. Rockers, G. Mbaruku, and S. Galea. 2009. “Household decision-making about delivery in health facilities: evidence from Tanzania.” Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 27(5), 696.

Ensor, T, and T Cooper. 2004. Overcoming barriers to health services access: influencing the demand side. Health Policy and Planning 19 (2):69-79.

Fanzo, J. 2015. “Integrating nutrition into rural advisory services and extension.” GFRAS Good Practice Notes for Extension and Advisory Services. Note 9. Lindau, Switzerland: GFRAS. https://www.g-fras.org/en/download.html?download=344:ggp-note-9-integrating-nutrition-into-rural-advisory-services-and-extension

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2005. Nutrition Education in Primary Schools. Vol. 1: The Reader. Rome: FAO. http://www.fao.org/3/a-a0333e.pdf

Franco, L.M., S. Bennett & R. Kanfer. 2002. “Health sector reform and public sector health worker motivation: a conceptual framework.” Social Science and Medicine 54: 1255–1266.

Kuyper, Edye, and Laina Schneider. 2016. “Conceptualizing the Contribution of Agricultural Extension Services to Nutrition.” Discussion Paper. Feed the Future and University of California Davis. https://agrilinks.org/sites/default/files/resource/files/ING%20DP%20Contribution%20Extension%20to%20Nutrition%20(Kuyper,%20Schneider).pdf

Leroy, Jef L., Marie Ruel, and Ellen Verhofstadt. 2009. "The impact of conditional cash transfer programmes on child nutrition: a review of evidence using a programme theory framework." Journal of Development Effectiveness 1(2): 103–129. doi:10.1080/19439340902924043.

Mukidi, Edith, Ruth Oniang’o. 2002. "Nutrition and Gender.” Nutrition: A Foundation for Development. Geneva: ACC/SCN. http://www.ifpri.org/publication/nutrition-foundation-development

Mumtaz, Z., and S. M. Salway. 2007. “Gender, pregnancy and the uptake of antenatal care services in Pakistan: Gender, pregnancy and antenatal care in Pakistan.” Sociology of Health and Illness, 29(1): 1–26.

Rao, GM Subba, D Raghunatha Rao, K Venkaiah, Anil K Dube and KV Rameshwar Sarma. 2006. “Evaluation of the Food and Agriculture Organization’s global school-based nutrition education initiative, Feeding Minds, Fighting Hunger (FMFH), in schools of Hyderabad, India.” Public Health Nutrition: 9(8), 991–995 DOI: 10.1017/PHN2006974

SPRING. 2017. Raising the Status and Quality of Nutrition Services. Arlington, VA. Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project.

----. 2014. Understanding the Women’s Empowerment Pathway. Improving Nutrition through Agriculture Technical Brief Series. Brief #4. Arlington, VA: Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2013. Improving child nutrition: the achievable imperative for global progress. New York: UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/publications/index_68661.html

----. 1990. Strategy for Improved Nutrition of Children and Women in Developing Countries. New York: UNICEF.

United Nations. 2017. "Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning." Sustainable Development Goals. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/education/

United States Agency for International Development (USAID). 2014a. Local Systems: A Framework for Supporting Sustained Development. Washington, D.C.: USAID. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1870/LocalSystemsFramework.pdf

-----. 2014b. Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy 2014–2025. Washington, D.C.: USAID. http://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1867/USAID_Nutrition_Strategy_5-09_508.pdf

-----. 2016. U.S. Government Global Nutrition Coordination Plan 2016–2021. Washington, D.C.: USAID. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1864/nutritionCoordinationPlan_web-508.pdf

Shah, Anwar, and Sana Shah. 2006. “The New Vision of Local Governance and the Evolving Roles of Local Governments.” Local Governance in Developing Countries, edited by Anwar Shah, 1–46. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/PSGLP/Resources/LocalGovernanceinDeveloping.pdf

Vistaar Project. 2008a. Improving Complementary Feeding Practices: A Review of Evidence from South Asia. Evidence Review Series 2. New Delhi, India: IntraHealth International, Inc. https://www.intrahealth.org/sites/ihweb/files/files/media/improving-complementary-feeding-practices-a-review-of-evidence-from-south-asia/ER_Brief_CF%202.pdf

Vistaar Project. 2008b. Improving Performance of Community-Level Health and Nutrition Functionaries: A Review of Evidence in India. Evidence Review Series, 6. New Delhi, India: IntraHealth International, Inc. https://www.intrahealth.org/sites/ihweb/files/files/media/improving-performance-of-community-level-health-and-nutrition-functionaries-a-review-of-evidence-in-india/ER_Brief_PI%206.pdf

World Health Organization (WHO). 2007. Engaging men and boys in changing gender-based inequity in health: Evidence from programme interventions. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. http://www.who.int/gender/documents/Engaging_men_boys.pdf

----. 2013. Essential nutrition actions: improving maternal, newborn, infant and young child health and nutrition. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/essential_nutrition_actions/en/

WHO, UNICEF, AED, USAID, and Africa’s Health in 2010 Project. 2008. Learning from Large-Scale Community-Based Programmes to Improve Breastfeeding Practices. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44011/1/9789241597371_eng.pdf?ua=1

The World Bank. 2007. From Agriculture to Nutrition: Pathways, Synergies and Outcomes. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/241231468201835433/From-agriculture-to-nutrition-pathways-synergies-and-outcomes

Zakiya, Afia, and Timeyin Uwejamomere. 2016. Rethinking decentralisation of WASH services in Ghana: Strengthening local assemblies to deliver services for all. London: WaterAid. http://www.wateraid.org/~/media/Publications/WASH-and-decentralisation-in-Ghana.pdf