How Community Video Encourages Male Involvement for Better Nutrition and Hygiene Behaviors in Niger

Evidence from the SPRING Community Video Experience

Executive Summary

BACKGROUND

Previous studies that explored interventions aimed at improving maternal, infant, and young child nutrition (MIYCN) behaviors primarily focused on the mothers of young children. Interest is growing in understanding how nutrition practices can be supported by involving other household members who provide social support and influence these practices, specifically mothers-in-law and husbands. In Niger, where the Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project has worked to improve nutrition since 2015, MIYCN behaviors are influenced by cultural norms and practices, including polygamy and an emphasis on male decisionmaking. In addition, literacy levels are low and the people who influence MIYCN practices are also influenced by the surrounding cultural and social norms and practices.

In this context, the SPRING project, supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has implemented a facilitated community video project to promote high-impact MIYCN and hygiene behaviors. Produced locally, the videos feature community members performing as actors and focus on many key themes, such as dietary diversity, handwashing, exclusive breastfeeding, and complementary feeding practices. Field mediators (or volunteers) share the videos with community groups, lead interactive discussions following the videos, and conduct home visits to address any questions raised by participants. During the home visits, mediators also ensure that group members understand the practice correctly and promote the practice to others in their family or community. Husbands in the community are exposed to video messages when they attend the video disseminations, during home visits, or when they learn about the health messages from their wives.

RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

To promote continued program learning, this report explains how the community video approach can be used to strengthen spousal communication and improve male involvement in MIYCN behaviors. Its major objectives are:

Objective 1: To understand how community videos influence couples’ dialogue about MIYCN and husbands’ involvement and support for MIYCN behaviors.

Objective 2: To explore how the SPRING community video approach can be used to encourage spousal communication and husbands’ support for MIYCN behaviors.

Objective 3: To assess how community members and important influencers, such as mothers-in-law, perceive changes in spousal communication and husbands’ support for MIYCN behavior after being exposed to the SPRING community video approach.

METHODS

We conducted the study in five villages in the Maradi region of Niger where the community video intervention was delivered. The study team—which included staff from SPRING, a local research partner, and consultants—used separate in-depth one-on-one interviews with husbands and their wives to determine how the community videos influence husbands’ support for MIYCN behaviors. We also used in-depth interviews with mothers-in-law and focus group discussion (FGD) with community members to assess perceptions of changes in spousal communication. In total, 20 women, 20 men, and 10 mothers-in-law were interviewed. We also conducted 10 FGDs with community influencers.

RESULTS

We explored findings from the qualitative research across the three study objectives, which are summarized below.

Objective 1: To understand how community videos influence couples’ dialogue about MIYCN and husbands’ involvement and support for MIYCN behaviors.

Men were exposed to MIYCN messages when they attended the community video meetings and when they talked with their wives, who also watched the videos. Watching the videos helped the men learn new information; reinforced knowledge they already had; and, in some cases, gave them a visual example of behaviors they could mimic. Exposure to the videos also enabled the men to accept the information more readily because they could see how the behaviors lead to improved health.

Most couples noted that discussions on MIYCN issues occurred in the evening or when they were not busy. Both fathers and mothers initiated conversations about the information shared through the videos and they generally agreed on decisions related to MIYCN without involving others. The conversations most frequently centered around what food to prepare for the family, the types of food to feed the child, and the transition to solid foods.

Objective 2: To explore how the SPRING community video approach can be used to encourage spousal communication and husbands’ support for MIYCN behaviors.

The study revealed that the community videos have helped the husbands understand the behaviors, while the visual examples showed opportunities for couples to imitate behaviors. The videos encouraged couples to take more of a shared responsibility for child nutrition instead of each parent working independently.

Objective 3: To assess how community members and important influencers, such as mothers-in-law, perceive changes in spousal communication and husbands’ support for MIYCN behavior after being exposed to the SPRING community video approach.

Overall, mothers-in-law and community members said the community videos helped encourage conversations between mothers and fathers about child nutrition, and these conversations had not occurred previously. These changes also caused an overall increase in conversations between fathers and mothers. Fathers started providing a higher level of support to the mothers in caring for the child.

CONCLUSION

Study findings indicate that community videos aid spousal communication in support of MIYCN behaviors even if husbands do not attend the disseminations. The visual presentation of MIYCN messages improved the transmission of information, which then facilitated communication between the husband and wife. Community members and family members confirmed these findings; they indicated that community video is a promising approach for strengthening spousal communication on important health issues.

Introduction

Located in the Sahel, Niger is characterized by harsh climate conditions that contribute to structural food crises and high rates of severe acute malnutrition among children. In 2012, the under-5 mortality rate was 127 per 1,000 live births, and 43.9 percent of children under 5 years were stunted (INS and ICF International 2012). Many factors contribute to the high levels of child deaths and malnutrition, including childhood illness and inadequate dietary intake. Underlying determinants for these intermediate causes include household food insecurity, poor child care practices, insufficient health services, and an unhealthy environment (Black et al. 2008). Many underlying determinants are influenced by cultural norms and practices, including polygamy, an emphasis on male decisionmaking, and low levels of literacy (Moreaux 2015). According to the 2012 Demographic and Health Survey, only 21 percent of women were able to seek health care for themselves without prior consent from their husbands; only 20 percent of women could make decisions about important household purchases (INS and ICF International 2012).

In this context, the Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project, supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), in collaboration with Digital Green, implemented a pilot intervention from late 2014 through 2015 to test the use of facilitated community video to promote high-impact MIYCN and hygiene behaviors. The project collaborated with three implementing partner projects to test the community video approach in their respective intervention villages. These partners are the Resilience and Economic Growth in the Sahel– Enhanced Resilience Program (REGIS-ER) and two Food for Peace projects: the Livelihoods, Agriculture and Health Interventions in Action (LAHIA) and Sawki projects. These projects are led, respectively, by the National Cooperative Business Association CLUSA International (NCBA CLUSA), Save the Children, and Mercy Corps. Implementation began in January 2015, first identifying 20 villages in the Maradi region: 15 in the commune of Guidan Roumdji under REGIS-ER and Sawki, and 5 villages in the commune of Aguie under Save the Children. A mixed methods evaluation on the acceptability, effectiveness, and scalability of the approach was conducted in mid-2015, and it determined that the pilot was effective in achieving improvements in MIYCN and hygiene behaviors (Dougherty et al. 2016).

In 2016, SPRING focused on transferring community video production and dissemination capacity to local partners, and the project began a rapid scale-up of community video activities in Niger. Building on the first phase of community video programming in 20 villages in Maradi, we supported the expansion of programming to an additional 54 villages in Maradi and 61 villages in Zinder, engaging three new partners.1 As a result, activities were scaled up in 2016 from 20 villages to 115—61 villages in Zinder and 54 in Maradi— reaching 460 groups (9,200 beneficiaries) with a video once a month. During this phase, SPRING worked with Digital Green and local partners to establish four video production hubs—two in each region of Niger—and to establish two technical advisory groups that would prioritize video content.

The videos feature local women and men in their own environment demonstrating key behaviors and overcoming barriers discovered during formative research. Using local families allowed viewers to observe the practices in a familiar context, being conducted and promoted by people of similar means in their own language. By seeing a neighbor practice a behavior, viewers understood that they too could do this and that they have the appropriate resources.

As of August 2016, 10 videos had been produced and disseminated in all the villages. Table 1 lists the title of each video and describes the specific content focused on male involvement. Each video showed a supportive husband who listened and talked to his wife/wives and who engaged in childrearing, two behaviors that are rarely seen publicly in the Niger context. Every video was pretested in advance for acceptability. Field mediators (or volunteers) shared the videos with community groups established by implementing partner projects, led interactive discussions following the videos, and conducted home visits to address any questions from the participants. They also confirmed if the group members understood the practice correctly, or promoted the practice to others in their family or community.

Table 1: List of Community Videos Produced and Description of Male Involvement Content2

| No. | Title of Video | Gender-Related Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Importance of the first 1,000 days | Wasila is accompanied by her husband to go to the health center where she learns she is pregnant. |

| 2 | Men Support Handwashing in Maradi | Men build handwashing stations and ensure availability of water and soap at the household level. |

| 3 | Responsive Feeding is Possible | A man washes his baby’s hands and patiently encourages her to eat, because his wife has to prepare herself to leave the house. In another household, the father supervises the children while they eat. |

| 4 | A Good Start to Exclusive Breastfeeding | A woman who has just delivered, practices exclusive breastfeeding and is supported by her family, including her husband. |

| 5 | How to Exclusively Breastfeed? | Aicha’s family helps her so she can exclusively breastfeed and her husband ensures Aicha has enough healthy food. Her friend, Zaru, asks the village mediator, to talk to her husband and mother-in-law asking them to support Zaru in exclusively breastfeeding her child. |

| 6 | How can we ensure dietary diversity in the Sahel? | A mediator picks moringa leaves and tomatoes in his garden and dries and stores them. When his wife prepares enriched porridge with the dried ingredients, their neighbor’s wife watches the preparation. |

| 7 | How can working parents feed their young children frequently? | While Rakiya and her husband work in the field, their older son feeds the baby with a healthy snack they brought to ensure the young child eats frequently. |

| 8 | All women need good nutrition | Hassan is preparing to go on a journey. He educates his family members to take care of Maimouna during her current pregnancy and lactation while he is away. |

| 9 | How to prevent and treat all diarrhea in children | In the home with the healthy children, Koni finds a latrine, a handwashing device, animals separated from the family’s living spaces, and water treatment. The man is shown sweeping the courtyard. |

| 10 | Harvest planning for a better future | A community advisor tells the men that they should discuss food consumption with their wives and divide the harvest into four parts: domestic consumption, seeds, health purposes, and other. The video shows two men following his advice and discussing with their wives. |

Through the SPRING community video approach, husbands can learn about MIYCN behaviors in many ways. First, husbands can learn about MIYCN behaviors as participants in the Ecole des Maris (EdM) or “husband school.”3 The EdM groups include approximately 12–20 men from the community who participate in regular meetings with a trained moderator to discuss primarily reproductive health issues. When a video is disseminated, they also discuss MIYCN. Men also learn about proper MIYCN behaviors by talking with their wives who are currently participating in women’s groups. Both men and women participating in the groups may also benefit from a home visit from the mediator who reinforces information presented during the videos. Members of the women’s group participate in facilitated discussions during community video dissemination meetings where key MIYCN behaviors are promoted. After a group meeting, women may return home to discuss the information they learned with their husbands. The third way that husbands may learn about MIYCN behaviors is through informal conversations with their peers. Each mechanism can contribute to improved understanding of issues, enabling improved spousal communication and support to adopt MIYCN behaviors.

Male Involvement

A number of studies have explored the role of grandmothers in supporting improved infant and young child feeding practices; they found that grandmothers play an important role in determining child feeding practices (Aubel, Touré, and Diagne 2004; Kerr, Berti, and Chirwa 2007; McGadney-Douglass et al. 2005). However, existing literature on the role of men in supporting maternal and child health has been limited to antenatal care and voluntary counseling and testing for HIV and AIDS (Katz et al. 2009; Theuring et al. 2009). Few studies have explored the role of men in supporting maternal and child health behaviors. The literature available on this subject suggests that spousal support does lead to greater use of health services (Biratu and Lindstrom 2006; Danforth et al. 2009; Mumtaz and Salway 2007). More research is needed to understand how spousal communication and support from husbands can encourage MIYCN behaviors.

Study Objective and Research Questions

Previous studies exploring interventions aimed at improving MIYCN behaviors have primarily focused on the mothers of young children. Interest is growing in learning how to support nutrition practices by involving other household members who provide social support and influence these practices, specifically mothers-in-law and husbands (Aubel 2011). Evidence from an evaluation of the SPRING community video approach in India in 2012 suggested that communication between women and their husbands increased after they were exposed to community video. Considering the limited existing research in this area, and the importance of male decisionmaking and low levels of women’s empowerment in Niger, interest is growing in understanding how to strengthen spousal communication and improve male involvement in MIYCN behaviors.

Figure 2. Word Cloud Showing the Most Common Words Coded Under “Support”

This report informs future efforts using the SPRING community video approach. Specifically, this report aims to address the following objectives and research questions:

Objective 1: To understand how community videos influence couples’ dialogue about MIYCN and husbands’ involvement and support for MIYCN behaviors.

1. How did the husband receive information about MIYCN and what did they learn? How did men’s behavior regarding these MIYCN behaviors change after learning this information?

2. What conversations did husbands have with their wives since learning about these specific MIYCN behaviors? Who initiated the conversations? When did they talk and where did they talk? Was anyone else involved in the conversation?

3. What changes occurred since having these conversations after viewing the community videos (i.e., increased communication between husband and wife, more support from husband with household chores)?

Objective 2: To explore how the SPRING community video approach can be used to encourage spousal communication and husbands’ support for MIYCN behaviors.

1. What factors have enabled communication and understanding of the role of men in supporting these MIYCN behaviors? What are some barriers to communicating with wives and understanding the role of men in supporting these MIYCN behaviors?

Figure 3: How Community Video Changes Male Involvement in MIYCN

Objective 3: To assess how community members and important influencers, such as mothers-in-law, perceive changes in spousal communication and husbands’ support for MIYCN behavior after exposure to the SPRING community video approach.

1. How do mothers-in-law perceive changes in the behavior of couples (i.e., both spousal communication and adoption of MIYCN behaviors) who have watched the community videos on MIYCN?

2. How do other community members perceive the changes in the behavior of couples (i.e., both spousal communication and adoption of MIYCN behaviors) who have watched the MIYCN videos?

Although some husbands may hear the messages through multiple channels, the study focuses on how husbands respond to messages they heard directly through the community video, as compared to husbands who heard the messages from their wives who saw the videos.

Study Design and Methodology

Study Setting, Design, and Sample

We conducted the study in five villages in the Maradi region of Niger where SPRING and Save the Children have worked since late 2014 to develop and deliver community videos. The study team used separate in-depth one-on-one interviews with husbands and their wives in the pilot communities to explore how community video and other social behavior change communication (SBCC) channels influence their support for MIYCN behaviors. In-depth interviews with mothers-in-law and FGDs with community members assessed the perceptions of changes in spousal communication.

In each of the five villages, the study team purposively selected respondents based on whether the woman or her partners had previously viewed a video. In some instances, we looked for respondents who had seen the videos and, in other instances, we looked for men who had not seen them. The first round of data collection occurred in August 2016. After the initial analyses were completed, we determined it was necessary to conduct a second round of data collection among men and women to reach greater depth and saturation on themes. The second round of data collection was completed in January 2017.

A summary of the respondents interviewed is presented in table 2.

Data Collection and Management

Interviewers trained to administer the guide in Hausa used an audio device to conduct all the interviews for the study. Specific training sessions focused on translating the questions into Hausa. Interviewers pilot tested the guide in a local community and then discussed any changes or suggestions to the guide to ensure the questions would be understood.

The interviewers identified respondents and asked questions only after obtaining authorized consent forms and verbal consent. Conducting the discussions in respondents’ homes, interviewers used a semi-structured, open-ended guide to facilitate the completion of the tool, which took a maximum of one hour.

After the interviews were completed, interviewers translated and transcribed the audio recordings. The team then inventoried all audio and written transcript files and recorded them on a separate tracking form. Only members of the study team (SPRING and local research firm) had access to the files, which did not include names. They stored and backed up all files on password-protected file drives. Levels of access were established prior to data collection to minimize version control challenges.

Table 2: Number of Interviewees by Category of Communication Channel and Sex

| Method | Communication Channel Category | Respondent | Number of Respondents August 2016 | Number of Respondents January 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-depth interviews | Only wife attended video dissemination | Husband (of woman with a child under the age of 2) | 2 per village (10 total) | 1 per village (5 total) |

| Wife (with a child under the age of 2) | 2 per village (10 total) | 1 per village (5 total) | ||

| Husband is member of EdM, wife is part of women’s group where the videos were disseminated | Husband (of woman with a child under the age of 2) | 2 per village (10 total) | 1 per village (5 total) | |

| Wife (with a child under the age of 2) | 2 per village (10 total) | 1 per village (5 total) | ||

| Mother-in-law | 2 per village (10 total) | NA | ||

| FGDs | Community member | 2 FGDs per village (10 FGDs total) | NA |

Analysis

To develop inductive and conceptual codes, the study team actively read and made notes on the transcripts. A codebook was developed with clear names and definitions. Because of the short timeline, it was not possible to assess an inter-coder agreement.

Findings were described and compared across sub-groups. Information retrieved was categorized into emerging themes, and the study team analyzed the findings to provide an explanation of the detail, variation, meaning, and nuance.

Results

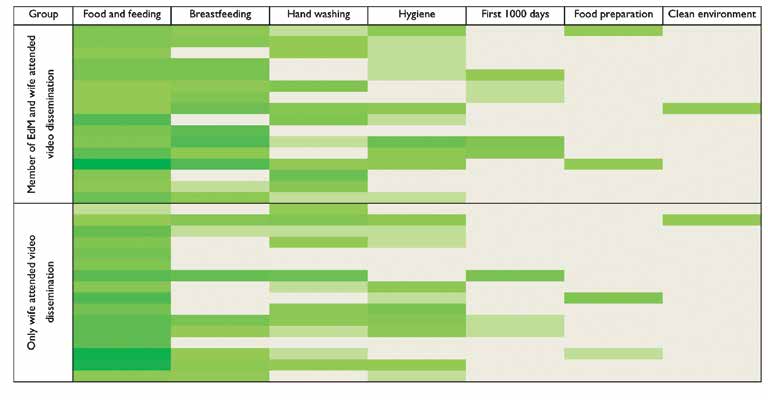

Figure 1. Heat Map of Common Maternal, Newborn, and Young Child Nutrition Topics That Husbands Learned About

Legend:

| Not mentioned | Mentioned a few times | Mentioned many times |

We organized the research findings by the three specific objectives outlined for the study.

Objective 1: To understand how community videos influence couples’ discussions about MIYCN and husbands’ involvement and support for MIYCN behaviors.

1. How did husbands receive information about MIYCN and what did they learn? How did men’s behavior regarding these MIYCN behaviors change after learning this information?

Husbands received information about the video content on MIYCN from their wives, who were participating in women’s groups where community videos were disseminated; from viewing the videos; or from discussions with their neighbors and friends, especially those whose friends are members of the EdM. They also received home visits from peer educators who talked to them about the videos and reinforced the messages. Through these channels, men reported that they learned about proper nutrition in the first 1,000 days of a child’s life—specifically, nutrition for pregnant/lactating women and children, handwashing and hygiene, food preparation and dietary diversity, and exclusive breastfeeding. There were no major differences in the MIYCN topics that the men reported learning about, regardless of how they received the information, but the most frequently reported themes were food and feeding (see figure 1). Although most respondents who saw the videos reported learning something new, a few said that they were knowledgeable about these topics before and were already practicing these behaviors; however, the videos reinforced these actions.

We talked about washing hands with soap and water. It’s a practice we’re already doing, but when we saw the videos, it reinforced us.

– wife

After viewing the community videos and learning this information, husbands were more accepting of these MIYCN behaviors and they acknowledged that the information benefits their families.

I think it’s a good thing if people understand these advices. They come to you and are told about these innovations for your good and your family [...] It [advice] must be copied in order to improve our living conditions.

– husband, seen video

Husbands who learned this information through their wives also appreciated the MIYCN behaviors and reported that the practice of the behaviors brought happiness to their lives and community because they now observe fewer sick children and have a healthier household. They acknowledged that these behaviors are important for achieving good health.

I am proud of these tips that help improve our health. My wife is going to her consultations and the people of neighboring villages appreciate this initiative very much. The children are in good health and our women give birth at the health center without complications.

– husband, not seen video

2. What conversations did husbands have with their wives since learning about these specific MIYCN behaviors? Who initiated the conversations? When did they talk and where did they talk? Was anyone else involved in the conversation?

Conversations between husbands and wives occurred mainly at night or early in the morning in the home. Some respondents reported that they had discussions whenever they were not busy. In general, either the husband or the wife initiated the conversations; in some couples, the husband and wife initiated the conversations equally. Most of the men who saw the community videos reported that they initiated these conversations with their wives, and a few said that their wives equally initiated the conversations. Men who did not view the community videos were more inclined to report that their wives initiated the conversations. A few men pointed out that their wives started conversations about the health of their children because they were the ones who were always with the children.

The mother [...] is always with the child. She knows more about him/her. You, the husband, it is only when you are at home that you inquire what happens and you ask.

– husband, not seen video

Both husbands and wives reported that they almost always agree whenever they discuss the health and nutrition of their household. Some acknowledged that it is normal to have disagreements, but they always agree or compromise in the end.

Couples discussed the nutrition of the household and the health of their children. More specifically, they talked about what their child had to eat or should be eating and how much, rationing food and money for groceries, complementary feeding and dietary diversity, exclusive breastfeeding, and how to keep their living space clean. One wife reported that she had a discussion with her husband about permitting her to continue attending dissemination meetings.

Some couples discussed the videos that both husband and wife saw or that only the wife saw. A husband reported that he and his wife discuss the videos and help each other understand the content.

Many times, when we come back from the video, we sit down and discuss what one of us has not understood, and we always [end up] [understanding].

– husband, not seen video

No other person was mentioned as being involved in these discussions between couples; however, separate discussions do happen between the husband or the wife and other members of the household—such as mothers-in-law or co-wives— about health and nutrition in the family, particularly the health and nutrition of the children.

3. What changes occurred since having these conversations after viewing the community videos (i.e., increased communication between husband and wife, more support from husband with household chores)?

Regardless of whether only the wife viewed the videos, both husbands and wives agreed that their conversations have improved greatly since the dissemination of the videos. One husband who viewed the community videos reported that he talked more often to his wife about health and nutrition, and these conversations were motivated by the community videos.

The conversation has been more motivated with the arrival of the video ... Since I started watching the videos, it’s me who brings the subject.

– husband, not seen video

In general, after we introduced the community video approach, couples had longer conversations about the health and nutrition of their household, discussed more topics, and both husband and wife were engaged in the conversations and could share their opinions. Many respondents reported that their conversations improved because they understood each other better. They functioned as a team when discussing the health of their household and when making dietary decisions for their family. Couples where both husband and wife viewed the videos were more inclined to report that their relationship was strengthened because they were more open, listened to each other, and had a mutual understanding. A wife who viewed the videos with her husband reported that he respects her more.

Before, I did not discuss with my wife, and we did not understand each other. But today we understand each other perfectly. When she returns after viewing the video, she gives me the account of all that she has seen and I apply it because of its advantages. It has contributed much to the strengthening of our bond of couple. Before, we could not discuss more than 10 minutes together. Now we spend over two hours chatting.

– husband, not seen video

We talk, my wife and I, to strengthen cohesion in the whole family. It’s mutual respect between everyone.

– husband, seen video

In addition to being more engaged in conversations about the health and nutrition of the household, husbands also provide more support to their wives since being exposed to MIYCN messages through the community videos (see figure 2). Husbands reported supporting their wives by encouragement, accompanying them or the children to the health facility, watching their children, participating in household chores, buying more varied food, buying products like cosmetics and soap, and providing money. One husband reported that women previously had home deliveries because the husbands opposed assisted delivery, but this was more expensive because of the complications that followed. So, now they are encouraging their wives to seek care for the health of their child. Another husband reported that he encourages his wife to maintain her antenatal consultations; while she is seeking care at the health facility, he stays home and takes care of their other young child.

I give her my full support. I encourage her to respect the schedule of her consultation, and I take care of the child while she is at the health center for her consultation. I’m proud of that.

– husband, not seen video

Many wives and husbands said that men were purchasing and bringing home more food, including more diverse and rich types of food. In addition to paying for groceries, several respondents said that husbands provided money to pay for medical fees and to cover the costs of consultations and medicines. Men were also said to have bought cosmetic products for their wives, including soap, perfume, and shea butter.

The support I give to my wife has evolved in the sense that I buy her cosmetics (soaps, perfume, oil). Before this project, I did not do it. I also bring her moringa leaves to improve and enrich her diet, and I do all the other domestic chores namely (transporting water, wood chore).

– husband, not seen video

There was no marked difference between the support provided by men who did not view the videos and those who did.

Objective 2: To explore how the SPRING community video approach can be used to encourage spousal communication and husbands’ support for MIYCN behaviors.

1. What factors have enabled communication and understanding the role of men in supporting these MIYCN behaviors? What are some barriers to communication with wives and understanding the role of men in supporting these MIYCN behaviors?

The reported behavior change among husbands after exposure to MIYCN topics was encouraged by the SPRING community video approach. Figure 3 presents a visual of how community videos enable behavior change. The tree graphic represents the themes and subthemes from the qualitative analysis that examined enablers for and barriers to encouraging or supporting MIYCN messages.

Using Nvivo, the transcripts were coded for “enablers” or “barriers” to encourage/support MIYCN references. Within these themes, references were grouped by subthemes. The results are further described in the following sections. First, the videos enabled behavior change because men saw the videos. Husbands affirmed that being able to see these behaviors in action during the videos made it easier for them to understand and helped them learn new topics in health and nutrition. One husband who saw the videos commented that the videos were “très cool,” so the observers mimicked the behaviors they saw.

The fact that we see images of real people on all aspects, and it’s easier to understand the tasks.

– wife

Other respondents who saw the videos confirmed the importance of everyone seeing these videos, including people such as co-wives, mothers-in-law, and community members. A mother-in-law recommended that the videos be shown to the men instead of having the women relay the information to their husbands, so that the men could see what the women were trying to explain. The videos would catch the attention of the men, just as they had the women. One community member suggested that the videos should be shared with anyone who had not viewed them. He also requested that the video production team increase the number of topics covered by the videos.

[I recommend] to show the videos to the men, to draw their attention also as they have drawn our attention. Instead of the woman explaining the video to her husband, it is better that the husband also goes to see the video. Also to create for the men their own videos.

– mother-in-law

Enable men to watch the videos so they can see what they are told so that they will be on the same page. And also if I forget, he can remind me.

– wife

Seeing a behavior being practiced in the home or community and recognizing its benefits was a second factor that encouraged behavior change.

What I have seen since the community videos project, my children have not fallen malnourished. On the contrary, they are in good health. I chat with my wife and we have a wonderful couple life with an enlightened mind. [There is] no problem with my family. Everything we do is positive.

– husband, not seen video

[Since] the dissemination of community videos, I advise my wife to seek consultation and I encourage her to go to the health center. We adopted birth spacing. As proof, you see this child playing, he is in good health.

– husband, seen video

A third factor that enabled communication and support for MIYCN behaviors was the open dialogue between husbands and wives. Many respondents confirmed that couples now agreed with each other when discussing the health and nutrition of their family. Conversations were more open and flexible, and couples agreed more. If a disagreement arose, they discussed it openly and agreed on a compromise. Even when one person was in charge of the health and nutrition issues in the home, the other person could be heard and could provide input through these conversations. Therefore, the videos facilitated increased dialogue among partners and the increased dialogue improved the learning about nutrition and hygiene behaviors in the household. The increased learning about the behaviors led to a shared responsibility in practicing the behaviors.

It is between the couple to take care of and maintain together the welfare of their children by improving service quality, state of health, and their food and [at the same time] taking together all the dimensions and burdens of having children. You see the responsibility is shared between husband and wife, which was not possible a few years ago.

– husband, not seen video

In addition, two respondents said they heard similar messages via radio; this helped them understand the topics better so they could engage in conversations with other family members. One husband, in particular, never saw the community videos but he heard similar messages on the radio about exclusive breastfeeding and the use of moringa. Hearing some of the same messages from another source, such as the radio, reinforced or validated to some extent the messages that he heard from his wife. Knowing a bit about the topics from the radio also enabled him to discuss these topics openly with his wife.

However, despite these enabling factors, some couples face barriers that may limit the practice of MIYCN behaviors in the home. A few couples mentioned that they rarely or never discussed family health and nutrition. One husband who viewed the videos reported that he leaves the decisionmaking to his wife and, therefore, does not ask questions because these topics are “pour la femme”(for women). Another husband who had not seen the videos said that he is away from the village for long periods of time as “marabout;” therefore, he did not have time to discuss these matters with his wife. A wife also reported that she does not discuss this with her husband at all, although they had both viewed the videos.

No, I did not discuss with my wife. But we copy all that we hear in public about awareness and she informs her co-wives on the same topics.

– husband, not seen video

Factors, such as money, also pose a barrier for families. One husband mentioning that the lack of money limited him in the frequency and amount of nutritious food that he could bring home to his family.

Every time that I have some money, I buy rich food as we were shown in the videos. I work within my means because it’s not always that I have money.

– husband, seen video

Objective 3: To assess how community members and important influencers, such as mothers-in-law, perceive changes in spousal communication and husbands’ support for MIYCN behavior after exposure to the SPRING community video approach.

1. How do mothers-in-law perceive changes in the behavior of couples (i.e., both spousal communication and adoption of MIYCN behaviors) who have watched the MIYCN videos?

From the perspective of mothers-in-law, the community videos brought health and nutrition topics, which were not often discussed, to the forefront of conversations between husband and wife.

There are also videos that have made a change because there are a lot of things that we did not know, and it was with the arrival of the videos that we became aware of all this.

– mother-in-law

Many mothers-in-law observed an increase in the frequency of communication between couples. They reported that both men and women were more engaged and interested in the health and nutrition of their families.

She [daughter-in-law] is interested in what I’m doing. Previously for anything, she would come to me only to bring me one of the children, but now she comes to see me herself. She is the one who washes the cups to put food.

– mother-in-law

They observed that couples practiced what they learned about MIYCN and confirmed that men supported their wives more by buying more food and taking part in household chores.

They take good care of their children. They buy essential and nutritious foods that they eat with their children. As soon as the woman is pregnant, they go to the health center and follow up as they have been told. They are having conversations more than before.

– mother-in-law

2. How do other community members perceive the changes in the behavior of couples (i.e., both spousal communication and adoption of MIYCN behaviors) who have watched the MIYCN videos?

Community members also confirmed the change in the behavior of couples, citing increased communication, couples being more involved in their children’s health and nutrition, and men being more supportive of their wives (see photos for visual image of change). Community of their wives (see photos for visual image of change). Community members observed an improvement in the health of children in the community, reporting that the children look healthier than before the videos were disseminated.

Mothers are very interested in the videos, and the evidence is that since these videos have started, children have become less sick.

– community member

Children who are exclusively breastfed are different from children who are not.

– community member

Discussion

It is increasingly recognized that to effect sustained improvement in household nutrition practices, we must use a wider approach that includes not only mothers, but also other influential household actors, such as men. Men often play a leading role in decisionmaking related to matters of the household; however, their involvement in promoting MIYCN practices is limited. They take a more indirect and supportive role by providing food and resources. In the context of Niger, this remains true, with men principally responsible for providing the food and financial support, while women have the daily responsibilities of caring for the child. The role of men in this shared responsibility makes them important influencers who need to be engaged when improving nutritional practices in the household.

Limited evidence is available on how to engage fathers and mothers to reinforce their roles in supporting improved child nutrition. Introducing the community video approach, particularly in a male-dominated society such as Niger, tests how men respond to new information on MIYCN. It also tests if exposure to new information, particularly when the behavior is modeled in a video, encourages improved spousal communication and support for MIYCN behaviors.

Through this study, we found that fathers responded favorably to the community video approach, which promoted a more family-focused approach to child nutrition—moving away from the mother-child group and to a more comprehensive form of care that includes the father. We found that the videos helped encourage spousal communication, which is uncommon in a traditional society such as Niger’s. Due to exposure to male involvement behaviors shown in the video, couples now see this type of behavior as something they would like to imitate.

Although the research showed no clear difference in dialogue between sets of husbands and wives who both attended the disseminations and couples in which only the/a wife attended, we still think it is necessary to show the videos to men because the society is patriarchal and the men have demonstrated considerable interest. They want to learn about child rearing, how to make life in the household more pleasant, and how to “discuss more with their wives.” For organizations that do not work with men’s groups, we recommend forming a group with male leaders to create social change. In addition, we recognize that multiple channels, including home visits by mediators, help to reinforce video messages with both the husband and wife.

Overall, the community video approach has had a favorable effect on increasing male involvement to improve MIYCN behaviors. Community videos, which show the contrast in behaviors when some husbands do not use proper behaviors compared to husbands who practice the desired behaviors, increases men’s understanding of the burdens mothers face in raising children and taking care of the home. This has encouraged men to take a more active role in managing the household and accepting childrearing responsibilities.

However, some barriers still need to be addressed. Although most couples talked about the issues more often, some couples said they did not discuss the behaviors, and some fathers said the issues around child nutrition were “women’s decisions.” Many men who live in the communities frequently work outside the communities for extended periods of time; this also limits the opportunities for men and women to focus on a shared responsibility for child nutrition. In these situations, it may be best to focus on other factors that can influence the husbands and provide support for mothers, including mothers-in-law and brothers-in-law.

SPRING should consider how videos can be made more widely available to these influencers—through cell phones or community disseminations, for example—and continue to disseminate new themes to increase their support. More research is needed to understand additional approaches that can be implemented to address these barriers. An approach that is more focused on community-based collaboration—involving other members of the community to ensure ownership and acceptability of the new gender norms—may help mitigate current limitations of the community video approach.

Conclusion

Study findings indicate that using community videos encourages spousal communication to promote MIYCN behaviors for most couples. The visual presentation of MIYCN messages facilitates the behavior adoption through imitation, enhances the transmission and comprehension of information, and increases knowledge of MIYCN topics. These factors facilitated communication between husband and wife. It is, therefore, important to continue to show supportive fathers and inter-couple discussions in future videos. Findings also show that men are the key influencers in the successful uptake of these MIYCN behaviors. Their active engagement in discussing nutrition practices with their wives—as well as their emotional, physical, and financial support—creates a sympathetic environment that encourages positive behavior change. These findings were confirmed by community members and family members, indicating that community video is a promising approach for strengthening spousal communication on important health issues.

Footnotes

1 IAOMD, PASAM-TAI, and la Direction de la Nutrition.

2 In fiscal year 2016, videos were disseminated in Maradi and Zinder in 115 villages with five partners. Three out of five partner projects implement EdM activities: LAHIA, Sawki, and REGIS-ER. In these 81 villages, one out of four groups were EdM, reaching approximately 1,215 men each month.

3 Videos are available for download at https://www.spring-nutrition.org/about-us/activities/improving-maternal-infant-and-young-child-nutrition-and-hygiene-through

References

Aubel, J., I. Touré, and M. Diagne. 2004. “Senegalese grandmothers promote improved maternal and child nutrition practices: the guardians of tradition are not averse to change.” Social Science & Medicine, 59(5), 945–959. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.044

Aubel, Judi. 2011. The roles and influence of grandmothers and men: Evidence supporting a family-focused approach to optimal infant and young child nutrition. Washington, DC: Infant and Young Child Nutrition Project.

Biratu, B. T., and D. P. Lindstrom. 2006. “The influence of husbands’ approval on women’s use of prenatal care: Results from Yirgalem and Jimma towns, south west Ethiopia.” Ethiopian Journal of Health Development, 20(2), 84–92.

Black, R. E., L. H. Allen, Z. A. Bhutta, L. E. Caulfield, M. De Onis, M. Ezzati, et al. 2008. “Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences.” The Lancet, 371(9608), 243–260.

Danforth, E. J., M. E. Kruk, P. C. Rockers, G. Mbaruku, and S. Galea. 2009. “Household decision-making about delivery in health facilities: evidence from Tanzania.” Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 27(5), 696.

Dougherty, L., M. Moreaux, C. Dadi, and S. Minault. 2016. Seeing Is Believing: Evidence from a Community Video Approach for Nutrition and Hygiene Behaviors. Arlington, VA: Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project.

Institut National de la Statistique (INS) et ICF International. 2012. Enquête Démographique et de Santé et à Indicateurs Multiples du Niger 2012. Calverton, Maryland, USA: INS et ICF International.

Katz, D. A., J. N. Kiarie, G. C. John-Stewart, B. A. Richardson, F. N. John, and C. Farquhar. 2009. Male Perspectives on Incorporating Men into Antenatal HIV Counseling and Testing. PLoS ONE, 4(11), e7602. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0007602

Kerr, R. B., P. R. Berti, and M. Chirwa. 2007. “Breastfeeding and mixed feeding practices in Malawi: timing, reasons, decision makers, and child health consequences.” Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 28(1), 90–99.

McGadney-Douglass, B. F., R. L. Douglass, N. A. Apt, and P. Antwi. 2005. “Ghanaian mothers helping adult daughters: the survival of malnourished grandchildren.” Journal of the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement, 7(2). Retrieved from http://jarm. journals.yorku.ca/index.php/jarm/article/ download/4987/4181

Moreaux, M. 2015. Informing video topics and content on MIYCN and handwashing: Situational analysis and formative research in Maradi, Niger. Arlington, VA: USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project.

Mumtaz, Z., and S. M. Salway. 2007. “Gender, pregnancy and the uptake of antenatal care services in Pakistan: Gender, pregnancy and antenatal care in Pakistan.” Sociology of Health and Illness, 29(1), 1–26. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.00519.x

Theuring, S., P. Mbezi, H. Luvanda, B. Jordan- Harder, A. Kunz, and G. Harms. 2009. “Male Involvement in PMTCT Services in Mbeya Region, Tanzania.” AIDS and Behavior, 13(S1), 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9543-0