This process documentation identifies the successes and challenges of establishing a multi-sectoral anemia platform in Uganda, analyzes the key factors that led to outcomes, and identifies potential areas for making improvements to the process in terms of sustainability of efforts. This process documentation uses data from two rounds of semi-structured qualitative interviews with key informants and all NAWG members, and observations by technical assistance providers.

Executive Summary

Anemia, a widespread public health problem, affects nearly 25 percent of the world’s population and undermines countries’ progress in health and economic development. Recognizing the scale and complexity of this problem, global and national commitment to address anemia in an integrated multi-sector approach is increasing.

Since 2012, the Ministry of Health (MoH) and stakeholders in Uganda have accelerated the country’s progress in anemia reduction. The USAID SPRING project, which engages with countries to strengthen multi-sectoral anemia programming at the national level by supporting country-led processes to create evidence-based and context-specific strategies to address anemia.

The National Anemia Working Group (NAWG), a multi-sectoral anemia coordination platform, chaired by the MoH, was constituted in 2014. The NAWG provided a critical platform for bringing diverse sectors and partners together to define and advance Uganda’s anemia priorities.

This process documentation identifies the successes and challenges of establishing a multi-sectoral anemia platform in Uganda, analyzes the key factors that led to outcomes, and identifies potential areas for making improvements to the process in terms of sustainability of efforts. This process documentation uses data from two rounds of semi-structured qualitative interviews with key informants and all NAWG members, and observations by technical assistance providers.

The interviews gathered informants’ perspectives about the NAWG’s function and strategic direction, multi-sectoral coordination and collaboration, anemia strategy development, and sustainability of anemia efforts. The key findings include—

- The NAWG must have high-level endorsements to begin work on a formal plan and to hold regular meetings.

- Dedicated staff are critical for successfully managing the logistics and process for NAWG meetings.

- The NAWG members are positive about cross-sector collaboration for knowledge sharing, networking, and relationship building.

- Minimal reporting can lead to a lack of accountability and being unaware of anemia reduction efforts being undertaken.

- The Anemia Action Plan (AAP) allowed for sharing of activity ideas across sectors, but additional steps were needed to foster the integrated activity implementation, which led to a comprehensive, multi-sectoral anemia strategy.

- Funding is a major barrier to sustaining anemia efforts and implementing the anemia strategy.

- District-level engagement needs to be strengthened because it is essential to effectively implement the anemia strategy.

- To continue meeting its objectives, the NAWG needs funding, coordination, and technical support from the donor community.

Introduction

Anemia, a widespread public health problem, affects nearly 25 percent of the world’s population. Currently, few countries are on track to meet the World Health Assembly (WHA) nutrition target of reducing anemia by 50 percent by 2025. Women and children in resource-limited settings bear the highest burden for anemia-related morbidity and mortality. Children with anemia have long-term, irrevocable cognitive and developmental delays, and decreased worker productivity as adults (Walker et al. 2007). Iron deficiency anemia contributes to adverse birth outcomes and it is the underlying cause of 115,000 maternal deaths and 591,000 perinatal deaths each year (Stoltzfus et al. 2004). In recognition of the scale of this problem, global and national commitment to addressing anemia continues to rise, shown by the specific focus on anemia in WHA’s six global targets to improve nutrition (WHO 2017).

The causes of anemia are complex and overlapping, and they include nutritional deficiencies, infections and inflammatory conditions, and genetic disorders (Balarajan et al. 2013). Because of anemia’s multi-factorial causes, interventions to address it span across multiple sectors and involve multiple stakeholders. Collaboration across sectors—including agriculture; education; health; and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH)—is critical to establish effective anemia prevention and control efforts.

Momentum is growing globally for multi-sectoral and integrated approaches to nutrition and a revived focus on anemia. Reducing anemia among vulnerable populations is critical to improve nutrition outcomes and to have a positive impact on maternal and child health and survival. The Government of Uganda (GoU), with support from SPRING, has worked with national sectors and stakeholders to strengthen multi-sectoral anemia programming at the national level and has created unified, comprehensive strategies, and plans to address anemia.

This report documents the anemia programming experience at the national level in Uganda, from October 2013 to August 2017. This process documentation uses data from qualitative interviews and participatory observation to uncover critical factors, including enablers and barriers for strengthening multi-sectoral anemia coordination; the goal is to provide this information to country stakeholders. It develops lessons learned and recommendations for next steps in Uganda, and it can be a useful perspective for other countries who want to make similar efforts to address anemia.

Overview of the Uganda Multi-sectoral Anemia Platform

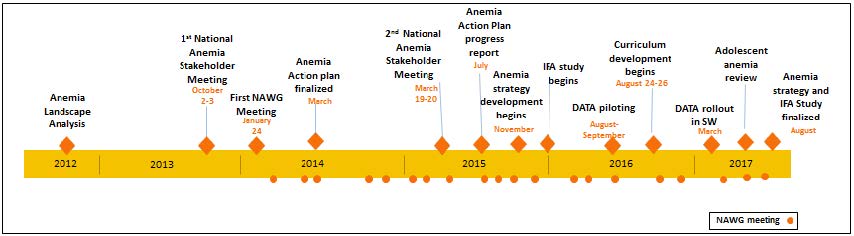

The multi-sectoral initiative to address anemia in Uganda, through SPRING support, spanned five years: 2012 to 2017 (see Figure 1). The effort started with a request from the GoU to SPRING to investigate the drop in anemia prevalence between 2001 and 2011 (shown by Demographic and Health Surveys). For women of reproductive age, the prevalence rate dropped from 36 to 24 percent; for children under 5, it dropped from 72 to 50 percent. Although the available data did not show exactly why they dropped, in 2012, SPRING worked with the GoU to identify several trends and potential areas where anemia-related programming could improve. They synthesized this information into a landscape analysis. With support from SPRING, the MoH organized the first Uganda National Anemia Stakeholder Meeting in October 2013. The meeting featured key points from the landscape analysis and presentations representing diverse areas of expertise and focus, including policies and programs for malaria, reproductive health, micronutrient supplementation in children, and biofortification. More than 100 people attended.

Figure 1. Timeline for the National Anemia Efforts in Uganda

After the stakeholder’s meeting, the MoH partnered with key sectors and stakeholders from that meeting to revitalize the NAWG, which was proposed in the National Anemia Policy of 2002, but was never constituted. The NAWG has representatives from different departments, divisions, and units within the MoH and other government ministries—Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF); Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development (MGLSD); Ministry of Education and Sports (MOES); Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development (MFPED); Office of the Prime Minister (OPM); and Ministry of Water and Environment, Ministry of Industry, Trade, and Cooperatives (MITC); and academia and research institutions; development partners (including United Nations agencies, civil society organizations, private sector organizations; including public and private not for profit entities, and health care institutions).

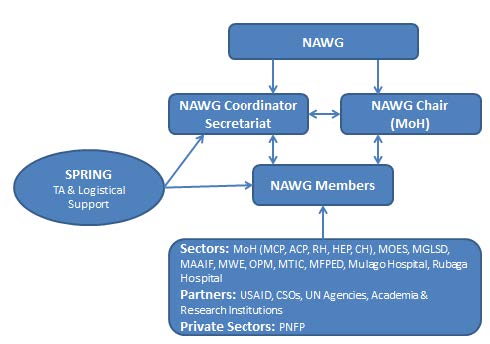

Members were nominated by the permanent secretaries of the key sectors (Figure 2). The Commissioner of the Community Health Department, under the MoH, accepted chairmanship of the group. The Senior Nutritionist and Micronutrient Coordinator from the Nutrition Division of the MoH formed the Secretariat, in addition to other officials within the Nutrition Division.

Figure 2: National Anemia Working Group Coordination Structure

During periodic meetings and with input from high-level officials and experts from multidisciplinary fields, the group established a list of key actions in the Uganda AAP to undertake from September 2014–2015. The AAP was finalized in March 2014, and the NAWG met almost monthly to share progress, as well as to discuss other anemia issues. In March 2015, SPRING and the MoH convened a second National Anemia Stakeholder Meeting to share progress on the AAP, to learn from a wider group of stakeholders, and to plan future activities. A progress report, based on the AAP, was developed in September 2015. The NAWG developed a national anemia strategy; they considered it important to set a collaborative platform to engage all sectors with a role in addressing anemia and to formalize this role with a comprehensive, multi-sectoral strategy for anemia prevention and control. The Uganda Anemia Prevention and Control Strategy 2017/18–2021/22 builds on past and continuing achievements in anemia reduction in the country, and it builds on the National Anemia Policy 2002. The strategy guides the implementation and monitoring of anemia-related interventions, and it is accompanied by a monitoring and evaluation plan and costed implementation matrix.

NAWG has also spearheaded many activities to contribute to efforts in addressing anemia. They supported the Mulago Health Tutor’s College (HTC) in developing a module that is included in the bachelor’s in medical education (BME) , which offers pre- and in-service teachers the knowledge and skills to train health professionals to address anemia. They also supported the integration of anemia prevention and control issues in the Functional Adult Literacy (FAL) curriculum in the MGLSD. Through the Mulago National Referral Hospital, they supported a study on iron-folic acid (IFA) supplementation for pregnant women. The study explored whether packaging of IFA supplements in a 30-tablet blister pack, instead of traditional loose packing in polyethene paper bags, would increase compliance with the recommended intake for IFA. Results from the study will inform national policy on IFA packaging and distribution to pregnant women in Uganda. The NAWG also conducted a situational analysis on adolescent anemia to document the best practices and gaps in implementing adolescent anemia interventions and to recommend policy and programming.

The adolescent review will be an advocacy tool to build awareness and commitment to focus on adolescent anemia in the country. At the district level, the NAWG has spearheaded the piloting and roll out of SPRING’s District Assessment Tool for Anemia (DATA) to strengthen planning for anemia.

Process Documentation: Rationale

Policy-making is a complex, dynamic process. As countries develop policies and plans to strengthen national nutrition programming, it is critical to understand the with respect to commitment, agenda setting, policy formulation, and implementation (Pelletier et al. 2012). Documenting the process, which identifies key challenges or constraints and enabling factors faced by policymakers and implementers, is useful for countries to plan and improve on policy formulation and implementation. This process documentation identifies the successes and challenges of establishing a multi-sectoral anemia platform in Uganda, analyzes the key factors that led to outcomes, and identifies potential areas for increasing sustainability. In addition, the NAWG and other stakeholders will use the documentation to support similar multi-sectoral approaches/platforms for cross-cutting issues, nationally and globally.

Methods

SPRING used a qualitative case study methodology for the process documentation in Uganda, which included in-depth interviews with key informants and participant observations by SPRING staff, who provided technical assistance. They conducted two rounds of semi-structured qualitative interviews. Round one was in March 2015, approximately one year after the AAP ended; it included 11 key informants. Round two was two years later, in March 2017, and included 12 key informants.

[The meeting] was a big eye-opener to many because…it has put forth how anemia is a multi-sectoral issue that cannot be addressed by one sector or one partner…the meeting has created awareness but also people understand what are the pragmatic areas, how the data that is available can be used to understand the issues or the gaps.

The key informants, all members of the NAWG, were selected to represent a range of sectors/institutions and different levels of involvement with the NAWG. The interviews gathered informants’ perspectives about the NAWG, including function and strategic direction, multi-sectoral coordination and collaboration, anemia strategy development, and sustainability of anemia efforts. The interview recordings were then transcribed and analyzed for emerging themes.1 To understand the background, context, and progress of the activities carried out by the NAWG, they also reviewed key outputs of the process. These documents included the AAP, Anemia Stakeholder Meeting workshop notes, AAP Progress Report, and the Anemia Prevention and Control Strategy. In this report, key findings are organized around the steps of the anemia platform building process.

Key Findings

The First Anemia Stakeholder Meeting: A Critical Agenda Setter

I think we realized that anemia involves teamwork. It is not an issue of one area.

For many, the Anemia Stakeholder Meeting was the first opportunity to convey the importance and the scope of anemia prevention and control. In Uganda’s first meeting, the group heard the anemia prevalence statistics, and heard speakers from a wide range of sectors and programs explain their relevance to anemia. Although the audience was diverse, the meeting imparted two key messages. First, for attendees less familiar with the subject of anemia, the process raised awareness on the severity of the issue in the country, as well as anemia’s underlying causes. Second, many interviewees (some familiar and some not familiar with nutrition) were convinced of the importance of using a multi-sectoral, coordinated approach to reduce anemia.

The importance of the stakeholder meeting for setting the tone and framework of the process was also shown in the resulting AAP. Participants at the NAWG meeting and some key informants, noted that additional areas should be included (e.g., WASH and hereditary sickle cell anemia) or further highlighted (e.g., gender and malaria); as well as additional implementing partners—at both the national and local level. Several NAWG members noted that the interventions in the AAP were largely based on the participants in the first stakeholder meeting. Thus, it was reflected that future anemia stakeholder meetings should, ideally, include all the relevant sectors and partners as early as possible, as well as define roles for each sector and partner to ensure a coordinated effort to address the multiple factors that contribute to anemia.

Establishing a National Anemia Working Group

The NAWG was established shortly after the stakeholder meeting. Several key informants noted difficulty in getting efforts launched, because the initial interim members had other responsibilities competing for their time; however, membership was later formalized through sector- and institution-nominated representatives. Informants identified many potential ways to support the sustained engagement of the NAWG:

There is a bit of team work at the personal level….that personal friendship that has developed over time… I think that will improve the working relationship between those ministries.

- High-level endorsement: In Uganda, although the first Anemia Stakeholder Meeting garnered several ideas for action items, developing anemia priorities was stalled for several months. Work started only after the Commissioner-Community Health Department in the MoH endorsed the process and directed the NAWG to work on a formal plan. High-level endorsement was also essential for the process logistically: the MoH provided the venue, and with the endorsement of the Commissioner and Director General Health Services, letters were written to permanent secretaries asking them to nominate an official to represent their sector on the NAWG.

- Having dedicated staff to manage the process: Conflicting schedules and competing priorities can pose challenges for managing planning meetings. Because the heads of the NAWG must be senior decision makers, they need assistance in managing meetings, compiling ideas for activities, tracking progress, and long-term strategizing. Many key informants expressed their gratefulness to SPRING for the smooth administration of meetings, frequent reminders, and follow up with individuals to prepare for and attend the meetings. Making sure the NAWG meetings have added value is probably tied to the NAWG members’ motivation to continue as part of the process, especially with the many competing priorities that were often cited.

Collaboration between NAWG sectors

Coordinating stakeholders across sectors is the central component of Uganda’s anemia platform. This multi-sectoral engagement is an opportunity for actors previously working independently to collaborate in the overarching goal of anemia prevention and control in Uganda. Despite a slow start at the beginning, the NAWG has become an active and participatory platform to coordinate anemia efforts. Between January 2014 and April 2017, the NAWG held 20 regular meetings, 31 secretariat and sub-group meetings for strategy development and review, 12 DATA pilots and rollout meetings and workshops, and 13 HTC curriculum development and review meetings.

Themes from stakeholder discussions involving cross-sector collaboration are as follows:

I was pleased because of that we managed to secure through SPRING, a strategy to incorporate anemia control in the curriculum of the teacher’s college. Which is our only college which trains all the people who are going to teach this midlevel healthcare workers.

- The NAWG members are positive about knowledge sharing collaboration; and, at times, believe that the integration of programs makes sense. Many key informants stated that the NAWG helped develop cross-sector working relationships and provided new and useful information. One informant believed that the working relationship between government ministries would improve over time because of the added cross-sectoral interaction that the NAWG provided. Several key informants went further to state that integrating programs across sectors would lead to improvements when the target population is the same (e.g., pregnant women, young children); it would increase cost efficiencies and quality.

- The NAWG collaboration led to beneficial informal relationships. Some key informants explained that the NAWG gave them potential resource persons outside their area of expertise. Stakeholders could use these new cross-sector relationships to support both anemia-related and other efforts. One informant mentioned efforts to produce and promote vitamin A-rich bananas, which was successful after collaborating with the MAAIF, MITC, and the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology.

- Formalizing sector reporting is important to capture informal activities. As NAWG members develop working relationships and increase their knowledge of anemia reduction efforts, some have implemented more integrated actions. To ensure the NAWG is aware of these efforts and reflects them in the strategy and implementation process, informants suggest establishing ways for sectors to formally report on efforts.

- Certain relationships were specifically identified as needing strengthening for the process; for example, between academia and various programmatic bodies (including the NAWG) to undertake research of particular relevance for implementation. In addition, the link between the NAWG and donors appears to need improvement.

- Curriculum development as an example of a formal collaboration from the NAWG. Through participation and coordination efforts by the NAWG, the MOES and the MoH collaborated to integrate anemia prevention and control modules into the HTC of Mulago's BME curriculum. The training package will give pre-and in-service teachers with the knowledge and skills to train health professionals to address anemia. This was a key first step in building capacity for anemia-related service delivery for health professionals. The NAWG also supported integration of anemia issues in the FAL curriculum with the MGLSD.

Implementation of Anemia Action Plan

I was pleased because of that we managed to secure through SPRING, a strategy to incorporate anemia control in the curriculum of the teacher’s college. Which is our only college which trains all the people who are going to teach this midlevel healthcare workers.

Compared with the results for raising awareness and improving cross-sectoral understanding of anemia, the process did not fare as well in implementing the AAP. Remembering the AAP only existed for one year, some reasons cited for this may improve over time, with experience. For instance, some key informants noted that the timelines included in the AAP were not realistic, and another noted that the plan needed a longer time span. Some also noted that the AAP was created with haste, although one key informant noted that “it is good we did it that way, because I felt that if we had to go through other processes, it would never start. But having started it, it has evolved.” They again noted that the AAP is a work in progress.

Many longer-term implementation issues emerged from the interviews and they should be considered as anemia efforts evolve in Uganda. These lessons learned were useful to the NAWG when they developed the national anemia strategy.

They were selected based on key sectors…we have an objective for disease control, for reproductive health, for nutrition, for education, for water and sanitation, and …not forgetting cross cutting areas like academia, monitoring and evaluation, advocacy, behavior change.

There may be a will, but…there may not be the necessary resources…It would have been a benefit if there was time and opportunity to be able to talk to my people in the planning department and my commissioner, and see how some of these proposed plans fit in with our budgeting framework.

- Balancing AAP tracking with other knowledge sharing. Several key informants noted the difficulty in tracking progress and disseminating information to the NAWG, perhaps partly because of the need to change and shift activities over time. For example, some key informants interviewed had differing information about the status of activities in the AAP. This probably impedes the problem solving and program learning within the NAWG. Moreover, changes to the plan, if not explained fully, may confuse the NAWG members who are not directly involved in implementation. On the other hand, key members of the NAWG may have issues with maintaining interest and variety in the meetings. The NAWG should ensure that information is regularly collected, yet is reported back to the NAWG efficiently and focuses on the issues that warrant group discussions or awareness. To that end, one key informant proposed that it may be useful to provide a summary progress update to NAWG members who are unable to attend.

- Concrete steps are needed to increase the integration of programs across interventions. While formulation of the AAP allowed for sharing of activity ideas across sectors, final activities still focus on the existing divisional mandates and working relationships. Additional steps should be taken to foster integrated activity implementation.

- Securing funding for new initiatives: Several key informants cited funding as a barrier to implementing AAP activities, which may be because they lack a dedicated budget line for anemia within governments, as well as lack donor involvement in the NAWG. Key informants cited additional efforts to attract funding for the AAP, such as advocating for specific activities to be added to sectoral government work plans, as well as clearly communicating to potential donors any underfunded priority activities.

- Integrating training and capacity building: Some key informants highlighted the need to develop and integrate training packages or curriculum to help build capacity at the intervention level, and to bridge the gap between policy and implementation.

Development of the Uganda Anemia Prevention and Control Strategy

Following the implementation of the AAP and tracking progress for one year (2014–2015), the NAWG began developing a comprehensive multi-sectoral anemia strategy. The strategy focused on fostering a multi-sectoral approach for all activities in the country without making major changes to the existing sectoral mandates. Key informants expressed that there was a strong multi-sectoral participation in developing the strategy. Each sector made significant contributions throughout the development process, making the strategy truly country owned. Because of this, informants felt all sectors were adequately represented and actions included were well situated in Uganda’s context. Key informant lessons learned from strategy development are as follows:

Especially when they brought in the element of costing, it has made us get more and more realistic, - the strategy still looks big, but we have thinned it down through the process – we [will] see [which] of the areas – may be too ambitious when we actually start implementing the strategy.

- Provide guidance on prioritization of actions. To help sectors prioritize what specific actions should be included in the strategy, informants expressed the importance of clarifying how each sector’s role related to anemia. While initially, some sectors suggested including all actions necessary to improve their general efforts, providing guidance on identifying those specifically important to anemia allowed the NAWG to create a more realistic set of objectives.

- Formalizing follow up helps keep stakeholders on the same page. Several informants expressed the importance of providing formal follow up after each meeting, including any strategy decisions or next steps. One informant explained the difficulty of moving forward with decisions when consistent attendance is uncertain. Keeping all NAWG members informed of both decisions, and the reasoning, was key to maintaining momentum to finalize the strategy.

- Consensus building was required to reach agreement on strategy. Developing the strategy through the NAWG provided the platform for different voices to be heard and to build consensus through discussion and then reflect this agreement in the final strategy.

- Political commitment will be critical. Key informants noted that the strategy was close to being final; the next step will be the formal approval and the government’s approval of the strategy. Some key informants were concerned that the strategy would not be approved by other sectors if it originates from the MoH; which was a different approach to the Uganda Nutrition Action Plan (UNAP), originating through the OPM. Others stated that the strategy is being shared with permanent secretaries, and they are confident that all sectors would give approval. After the strategy is approved, dissemination at all levels (national to district) and across all sectors will be required.

- Integration and funding are essential to implementing the strategy. As sectoral representatives of the NAWG have shared the strategy with their respective commissioners, informants stated that the sectors will commit and expect they will incorporate the strategy into their mandates. Several informants expressed that the strategy activities will need to be integrated within the implementation framework of each sector, aligning with annual work plans and budgets, and monitoring indicators.

Engagement at the District Level

I believe the districts are more important because they actually observe the anemia issues – they’re actually directly involved, so I think maybe to improve our structure of these meetings, we may need them.

Although the NAWG expressly operates at the national level, many key informants felt that engaging district-level stakeholders in anemia reduction efforts was important, both to sustain interest among working group members, as well as to ensure that the strategy will have impact. The NAWG has piloted DATA in three districts—Amuria, Arua, and Namutumba—and rolled out the DATA in several districts of the South Western region. To support planning and prioritization at the sub-national level, it continues to provide technical support to other partners rolling out the tool. However, key informants report that district-level engagement needs strengthening.

Themes involving district-level engagement include—

- District-level engagement enhances context specificity. Several informants explain that engaging stakeholders at the district level provides information about the local anemia situation and the barriers and enablers to programming for anemia prevention and control. It also provides information on the implementation context, including the availability of resources, like staff and funding, and the capacity of implementers. This allows for understanding the feasibility of implementing activities better at the district level, and it is essential for effectively implementing the strategy.

- Advocacy for the strategy activities can increase through district-level stakeholders. Informants suggest that district-level stakeholders are an important actor to engage in advocacy efforts. District-level stakeholders involved in anemia prevention and control efforts are in a key position to advocate for (1) inclusion of strategy activities in district work plans and budgets, and (2) sensitization of the public to demand the services that contribute to reducing anemia (e.g., IFA supplementation, deworming, iron-rich diet, etc.).

At this level it is issues of policy, guidelines…we need to be seen as moving away from these conference rooms to the field where the people are, so we can have an impact.

- District-level engagement requires strengthening links and sharing resources from the national to the district level. To successfully engage district level actors, it is important that NAWG meeting outputs and resources are accessible to district level counterparts. While it is not feasible to invite all district officials to the NAWG meetings, outreach and periodic visits to districts are possible. The District Nutrition Coordination Committee (DNCC) would be a logical place to begin and it is in line with their mandate of coordination across sectors. Further, using DATA has increased the collaboration between the national level and the district level actors, because the NAWG—with support from SPRING—has facilitated the workshops. Dissemination and support for implementation of the strategy will also strengthen this link between policy and programmers. Key informants have noted that after the strategy is rolled out, it will involve the lower levels of management at the district and sub-county level, which will create an enabling environment for sustainability using a participatory approach.

Sustainability

Political will enables all positives. It brings the financial aspects - and that is the enabling power[.] -from my assessment, we have the strategy, we have the interventions, we have the knowledge, we have the informed people on board, what we have left with are the finances.

Much of key informant discussions focused around sustainability of the NAWG and National Anemia Strategy as SPRING transitions out of its supportive role, and the next steps necessary to maintain momentum for strategy implementation and related efforts.

Common themes include—

- Implementation of the strategy also needs to be a multi-sectoral effort. While informants described the strategy development process as truly multi-sectoral, they expressed concern as to whether this would continue during implementation. One key informant explained the difficulty with implementing a multi-sectoral strategy as, “We seem to integrate and work well when it comes to identifying issues, planning, but [not] when it comes to implementation…which involves resources. The selfish element comes in.” Although the NAWG appears to have laid the foundation for collaboration by building cross-sectoral relationships, informants explained that more work is needed to clarify each sector’s role in the integrated activity implementation.

- Securing funding is a common concern among key informants. As with implementation of the AAP, many informants discussed the importance of securing funding for the strategy objectives. Informants mention several ways they envision the strategy funding structure, including advocating for each sector to incorporate the actions into their own plans and budgets; engaging the MFPED in the NAWG to convince them of the importance of funding the strategy; and relying on donors or external funders. Stakeholders also expressed that district-level actors should understand the importance of addressing anemia to engage more voices in advocating for anemia prevention and control actions to be incorporated into sector plans and budgets.

- Funds, political will, and human resources capacity are all necessary for strategy implementation. Many informants explain that securing funding will be more likely if the NAWG can engage political leaders in advocating for adopting the strategy. Political leaders can also support sensitization of the public to create a demand for services included in the strategy. For strategy implementation, informants also explained that having adequate technical staff is essential. The NAWG relies on stakeholders’ ability to participate in meetings while, simultaneously, maintaining their day-to-day workloads. During implementation, it will be important to have technical cross-sector staff with time specifically dedicated to anemia prevention and control.

- Formalize individual sector roles and accountability to ensure everyone is playing their part (accountability). As mentioned above, implementation of the strategy requires continued multi-sectoral efforts. Informants explained that for efforts to be successful, each sector must have their anemia efforts clearly defined and they must be held accountable. Some informants suggest it would be beneficial to develop a formal system for reporting to the group on each sector’s progress, successes, or barriers experienced to ensure that NAWG members stay informed about each sector’s efforts and can provide support, if needed.

- To ensure sustainability, SPRING’s role in the NAWG will need to be filled. Currently, SPRING offers NAWG support through funding, coordination of meetings—including sending SMS reminders and follow up—and technical support. Informants recognize that the NAWG will need to transition these responsibilities to more sustainable ownership when the SPRING partnership ends. Informants explained that adopting the strategy as policy could help create a stable structure to maintain the cross-sector coordination essential to sustaining anemia efforts.

Maintaining Momentum for Anemia

After SPRING, [then] what?– Unless SPRING is going to be here until kingdom come, we have to find another way to sustain the program.

The anemia platform strengthening process appears to have initiated a meaningful shift in high-level awareness and motivation to reduce the anemia burden in the country. Translating this sentiment into multi-sectoral action through the NAWG has presented challenges, such as competing priorities and lack of funding for new activities. In addition, several key informants expressed views about the prospects for the NAWG’s long-term sustainability. On one hand, some key informants felt that because the process is country-led, the NAWG could be more sustainable, or eventually be institutionalized—such as including the NAWG as a line item in the national budget—compared with having support from an external partner, such as SPRING. Further, a country-led multi-sectoral approach leads to improved coordination and collaboration and reduces the potential for activities changing with donors’ shifting strategic direction. At the same time, some key informants expressed their uncertainty about whether the NAWG would continue after SPRING support ended. Lessons learned from the process (summarized below) are not only important for the short term, but also for the sustainability of the anemia platform. Maintaining momentum for anemia will take the full institutionalization of the NAWG, dedicated funding for the NAWG activities, and effective implementation of the anemia strategy.

Key Lessons Learned

- Endorsements from high-level officials and having dedicated staff to manage and coordinate the process is essential to sustaining engagement.

- Membership overlapped with other coordination platforms—for example, UNAP, Micronutrient Technical Working Group (MN-TWG), National Working Group on Food Fortification (NWGFF)—which could be better linked and streamlined.

- Conflicting commitments and competing priorities were sometimes a barrier to engagement in the working group meetings.

- Providing all members with a solid foundation of anemia knowledge was required and was achieved through technical presentations. The knowledge gained across sectors and levels allowed a shift in the country’s approach to addressing anemia—from a health sector approach to inclusion of non-health sector partners.

- The anemia platform facilitated networking opportunities, stronger working relationships, and enhanced collaboration between sectors/stakeholders.

- The timeline for developing the AAP was too short: additional time and effort should be dedicated to developing the AAP and streamlining the process for gathering this information.

- The shortcomings of the AAP led the NAWG to develop a more comprehensive multi-sectoral anemia strategy, and included a costed plan for implementation and a monitoring and evaluation plan. The multi-sectoral and collaborative process to develop the strategy allowed for feedback from relevant sectors and obtained high-level political commitment, resulting in a country-owned and context-specific document.

- Lack of a dedicated budget line or a defined process within the multi-sectoral anemia platform to access funding affects the ability to implement new or additional activities. With the costed implementation matrix for the anemia strategy, the aim is to ensure a budget line and adequate funding for the prioritized activities.

- District-level involvement and linkages to existing sub-national structures is weak and should be emphasized to support prioritization of strategy actions and create effective feedback loops.

- Implementation of DATA was critical to link multi-sectoral anemia efforts from the national to the district level, generate awareness on anemia, assess anemia-related programs, and prioritize action at the district level.

- DATA enabled the different sectors at the district level to understand how they can address anemia through increased integration of activities and sharing monitoring data to assess progress. It also reflected the importance of engaging with different implementing partners (e.g., USAID/Regional Health Integration to Enhance Services) so that efforts can transition from one partner to the next.

- Integrating DATA into existing district-level structures and training staff from all relevant sectors will foster ownership by the districts to continue improving efforts to address anemia. It also allows for advocacy to collect more data and to use data across sectors to track progress for anemia.

- Monitoring, accountability of results, and sharing progress needs to be more systematic. This was apparent when tracking the AAP and will continue to be important for tracking implementation of the anemia strategy.

- Although awareness about anemia has increased at the national level within the working group and across sectors and, also, in select district level sectors—those involved in piloting and roll out in the South Western region—much more should be done to advocate for addressing anemia, at all levels, and for creating a demand for services.

Recommendations/Next Steps

NAWG:

- Determine ownership of anemia coordination efforts at the national level, which will be key for sustaining of the NAWG after the SPRING partnership ends.

- Ensure that the NAWG is institutionalized within the MoH as a coordination platform, with a formal budget line item for coordinating meetings.

- As membership is overlapping and the main secretariat member is the same in all three groups, consider merging the three working groups—NAWG, NWGF F, and MN-TWG—into one large coordination body with technical subgroups for different anemia interventions.

- Strengthen alliances with specific sectors that were seen as having weaker linkages (i.e., academia and research; private sector).

- Share information, updates, and resources to select regional and district officials so that implementation-level staff have the most relevant information they need.

- Establish a mechanism where all sectors and districts report the progress in implementing anemia activities. This would aid monitoring and identify gaps where support is needed.

Anemia Strategy:

- Disseminate the anemia strategy at the national level, across all government sectors and partners. Implementing partners at the regional and district level should consider disseminating the strategies at the different levels.

- Develop an abridged version of the anemia strategy for the district audience. Disseminate the anemia strategy across all government sectors and partners at the district level.

- Integrate the interventions in the anemia strategy into the sectoral work plans and budgets and, also, supported by or harmonized with partner activities, where feasible.

- During the next five years of implementation, the government sectors can use the indicators and the targets in the anemia strategy to track progress.

- Explore integration of activities across sectors, where feasible. This can include strengthening platforms to co-deliver anemia-related interventions, such as deworming and nutrition/hygiene education in schools.

- Within the five years of this anemia strategy, consider advocating for collection of better data at the national level, particularly conducting a micronutrient survey; and, also, integrating anemia-related data into national surveys (i.e., agriculture and education surveys).

District Level Engagement through DATA:

- Consider a regional-level DATA training to build capacity for all regions in the country: Use the national-level NAWG and SPRING facilitators who were involved in the DATA pilot and the roll out in the South West region to conduct a master training-of-trainers for regional trainers and/or district level coordination focal persons (e.g., DNCC and District Health Management Committee [DHMC]) for DATA. These regional trainers can then cascade the training to new facilitators at the district level.

- Use DATA with the interventions to be implemented and strengthened in the anemia strategy. After the anemia strategy is disseminated at the district level, implementation of DATA can follow just before the annual district planning cycles for the following year.

- During the first implementation of DATA in each district, determine how prioritized activities will be monitored and how progress will be shared—this should be directly aligned with the process for monitoring the anemia strategy implementation. Also, determine the frequency of DATA use (i.e., suggest every year prior to district work planning).

- Ensure that DATA is linked to the local coordination platform by building the capacity of the DNCCs and DHMCs to coordinate anemia efforts and ensure sustainability.

- When expanding DATA to other districts in the country, prioritize those with the high prevalence of anemia, if resources are limited.

- Explore options to harmonize activities with partner-driven implementation of anemia-related interventions.

Advocacy:

- To address advocacy needs, consider forming an advocacy technical group within the working group, or use the existing advocacy platforms to integrate anemia. Work closely with the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology and implementing partners supporting advocacy efforts.

- Through the anemia strategy, develop plans for how to advocate at different levels and to different audiences at the national, district, and community levels.

- Use lessons learned from high profile, expansive communications campaigns that have successfully been carried out in the country (i.e., human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]) to make a “slash” on anemia, to ensure it is an issue that everyone knows about. Highlight the consequences and gains related to anemia that different audiences can understand.

- Consider using “anemia champions” at all levels, particularly at the community level (i.e., opinion, religious, local government leaders) to help advocate and encourage community members to use and demand anemia-related services.

To view the annex, please download the full report above.

Footnotes

1 The quotations in this report are excerpted from these interviews and attributed to anonymous NAWG members.

References

Balarajan, Yarlini, Usha Ramakrishnan, Emre Ozaltin, Anuraj H. Shankar, and S. V. Subramanian. 2011. “Anemia in Low Income and Middle-Income Countries.” The Lancet 378 (9809): 2123–35.

Ezzati, M., Vander Hoorn, S., Lopez, A., Danaei, G., Rodgers, A., Mathers, C., and C. Murray. Edited by A. Lopez, C. Mathers and M. Ezzati. 2004. “Comparative Quantification of Health Risks: Global and Regional Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risk Factors.” Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Pelletier, D. L., E. A. Frongillo, S. Gervais, L. Hoey, P. Menon, T. Ngo, R. J. Stoltzfus, A. M. S. Ahmed, and T. Ahmed. 2012. “Nutrition agenda setting, policy formulation and implementation: lessons from the Mainstreaming Nutrition Initiative.” Health Policy and Planning 27:19–31.

USAID Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy 2014–2025: http://www.usaid.gov/nutrition-strategy

Walker, S. P., T. D. Wachs, J. M. Gardner, B. Lozoff, G. A. Wasserman, E. Pollitt, and J. Carter. 2007. “Child development: risk factors for adverse outcomes in developing countries.” The Lancet 369 (9556): 145–157.

World Health Organization. 2014. World Health Assembly Global Nutrition Targets 2025: http://www.who.int/nutrition/global-target-2025/en/