Exploring Opportunities for Future Investments in Nutrition Social and Behavior Change Communication

Nigeria's Federal Ministry of Women Affairs and Social Development estimates that there are 17.5 million orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) nationwide. These children face enormous challenges to their health and development and it is estimated that 95 percent of OVC do not receive any type of medical, emotional, social, material, or school-related assistance (National Population Commission, Federal Republic of Nigeria, and ICF International 2013). Childhood malnutrition is one of the major causes of childhood morbidity and mortality in Nigeria and a cross-sectional study of 2015 revealed that more than a quarter of OVC studied showed symptoms of mild to moderate malnutrition. In addition, close to 70 percent experienced household food insecurity, putting them at risk for malnutrition (Tagurum et al. 2015).

Nigeria is currently expanding its support to OVC as well as their caregivers, households, and communities through the rollout of the 2014 National Standards for Improving the Quality of Life of Vulnerable Children. A significant programming challenge is ensuring that OVC have access to a diverse and nutritious diet. As caregivers become ill or die, household labor supply is diminished, which dramatically affects income and/or the ability to cultivate land. Access to nutritious foods dwindles and families often resort to harmful coping strategies to survive. Complicating this scenario, those individuals living with HIV have higher energy requirements.

There are many civil society organizations (CSOs) working with OVC in Nigeria, providing nutrition counseling and education. Two consortia working with the USAID-funded Umbrella Grant Mechanism (UGM) OVC Project, Sustainable Mechanisms for Improving Livelihoods and Household Empowerment (SMILE) and Systems Transformed for Empowered Action and Enabling Responses for Vulnerable Children and Families (STEER), are projected to reach over one million OVC in 10 states between 2013-2018 through their partner civil society organizations (CSOs). The Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and innovation in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project has been asked by USAID/Nigeria to work with SMILE and STEER to find innovative ways to reach OVC ages 2-17 through social and behavior change communication (SBCC) programming.

This report is intended to provoke discussion and catalyze change among existing nutrition and OVC institutions, decision-makers, practitioners, and influencers. Since USAID has included SBCC as a key activity in its 2014-2025 Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy, greater emphasis on SBCC in OVC nutrition programming in Nigeria is timely and appropriate. SPRING is well positioned to support the design of at-scale OVC nutrition SBCC platforms and the implementation of programming by UGM partners.

After reviewing global and Nigeria-focused research, existing nutrition-focused OVC SBCC materials and other resources, as well as the results of surveys conducted among CSOs working with the UGM OVC Project, SPRING proposes to engage with its OVC partners to: 1) review the Recommended Menu of Options outlined below; 2) determine the acceptability and appropriateness of these various ideas; 3) prioritize specific materials and interventions for the different age group; and 4) support the development/adaptation of the options that are prioritized Priority will be given to those materials and interventions deemed to have the highest potential for successfully engaging OVC populations and their caregivers.

| Life Stage | Recommended Menu of Options |

|---|---|

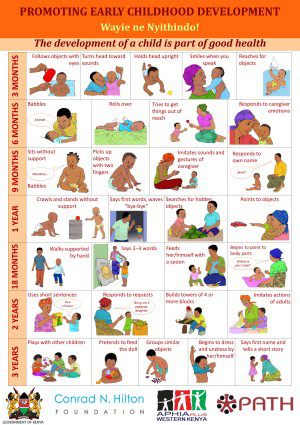

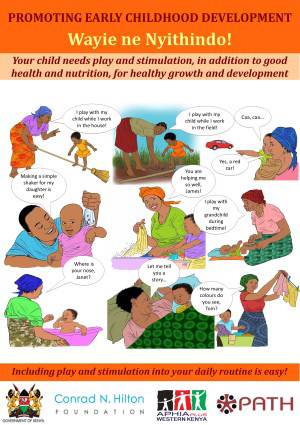

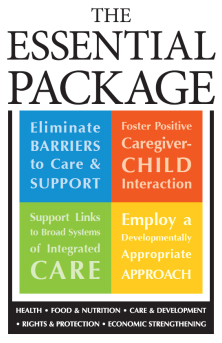

| Early childhood: Ages 2 - 5 | 1. Adapt PATH's early childhood development (ECD) package materials from Kenya and Mozambique (counseling cards, group session cards, posters and toy kits) with age appropriate nutrition messages and activities. 2. Adapt materials from the Essential Package created by CARE, Save the Children, and the Consultative Group on ECD with age appropriate nutrition messages and activities. |

| Middle childhood: Ages 6 - 11 | 1. Adapt the NCBA CLUSA Yaajeende school notebooks and nutrition-focused game(s) for students. 2. Adapt the "Getting Ready for School: A Child-to-Child Approach" teaching materials, such as the guides for teachers and young facilitators, and thematic flyers with age appropriate nutrition messages and activities. 3. Create easy-to-read booklets and comics with nutrition-specific SBCC information. |

| Late childhood: Ages 12 -17 | 1. Reach out to community and regional radio programs to train adolescents to create radio jingles with nutrition messaging and pre-developed audio material with Q & As.2. Use Shakthi or another youth engagement platform such as Facebook, WhatsApp, or 2go to send out tips, advice, and guidance on proper nutrition. 3. Use mobile technology to send out a SMS of the day/week such as "Family Nutrition 101." 4. Adapt the Boys & Girls Club "Triple Play" in after-school sports programs, focusing on improving the overall health of OVC by increasing their daily physical activity, teaching them good nutrition, and helping them develop healthy relationships. 5. Adapt SPRING's work with Digital Green (DG) to support youth to develop videos with nutrition messaging that can be shared and transferred to DVDs and/or audio on SIM cards. (Strengthening Partnerships 2013). |

Background

During fiscal year 2014 (FY14), USAID/Nigeria asked SPRING in Nigeria to support the introduction and rollout of the Community-Based Infant and Young Child Feeding (C-IYCF) counseling package. Over the last two years, SPRING organized a series of training-of-trainers (ToT) workshops for the counseling package, and provided technical assistance to civil society organization (CSO) staff working under the Umbrella Grant Mechanism (UGM) Orphans and Vulnerable Children (OVC) project, health facility staff, and community volunteers responsible for leading C-IYCF support groups.

The UGM is a five-year U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded project designed to mitigate the impact of HIV and AIDS on Nigerian children and their families by creating greater country ownership and leadership of HIV and AIDS programs. It does so by strengthening government agencies, CSOs, and individual families. The overall goal of the project is to reach approximately one million OVC as well as 250,000 caregivers in the states of Bauchi, Kaduna, Kano, Edo, Sokoto, Federal Capital Territory, Benue, Kogi, Nasarawa, and Plateau. The UGM was awarded to two consortia: Sustainable Mechanisms for Improving Livelihoods and Household Empowerment (SMILE) and Systems Transformed for Empowered Action and Enabling Responses for Vulnerable Children and Families (STEER). The STEER consortium is led by Save the Children (SC), and includes the Association for Reproductive and Family Health, the American International Health Alliance, Management Sciences for Health, and Mercy Corps. The SMILE consortium is led by Catholic Relief Services and includes ActionAid and Westat.

In FY15, USAID/Nigeria asked SPRING to support the UGM to achieve an increase in OVC households' access to nutrition and food security resources. An initial step in this process was to review current OVC programming in Nigeria under the UGM and identify opportunities to develop state-of-the art nutrition social and behavior change communication (SBCC) programs and materials targeting OVC ages 2-17. In FY16, SPRING plans to develop materials to support the CSOs' nutrition programming for OVC based on the recommendations from this report.

Goals and Objectives

The goal of this review is to inform the development of a SPRING-supported nutrition literacy package, with a menu of options for USAID-funded implementing partners in Nigeria working with OVC and their caregivers. Specific objectives are to identify—

- the magnitude of the OVC problem globally and in Nigeria

- key elements of Nigeria's response to the OVC crisis

- promising nutrition-focused SBCC interventions by life stage that have potential for adaptation with the OVC population

- a recommended menu of nutrition-focused SBCC delivery strategies for OVC at each life stage that includes SBCC materials and program guidance to support OVC nutrition interventions in all UGM partner states.

Methods

SPRING conducted a desk review of available published reports and other project and program documents — including peer-reviewed and gray literature — related to nutrition, OVC, and SBCC, with emphasis on OVC interventions globally and in Nigeria. Materials included formative research and other studies, previous assessments, project reports, and surveys.

Subsequently, SPRING/Nigeria conducted three surveys with CSOs working under the USAID-funded OVC UGM. Collectively, these CSOs have reached one million OVC in 10 states over the past three years. Seventeen CSOs participated in an initial survey in December 2014, 51 CSOs participated in the second survey in April 2015, and 39 CSOs participated in the third survey in June 2015. SPRING/Nigeria designed these surveys to obtain information on current OVC-related activities and programs that SPRING could potentially build or expand upon, and to capture information on the technology capacities of OVC caregivers and older OVC, as well as the internal technology capacities of participating CSOs. See the References and Resources sections for lists of publications and documents used, Annex 2 for a full list of the CSOs surveyed, and Annex 3 for detailed survey findings.

Findings

1. Defining Orphans and Vulnerable Children Globally

Defining the term OVC is the first step in understanding the magnitude of the OVC problem and the responses offered by various United Nations and donor agencies, including USAID, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and governmental ministries. It is also a critical step in determining the types of nutrition SBCC programming that may have the greatest impact for OVC populations in Nigeria.

In 2004, the World Bank established an OVC Thematic Group to respond to the worldwide OVC crisis due to HIV and AIDS, and developed an OVC toolkit for sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (World Bank Africa Region and World Bank Institute 2005).

The World Bank defines OVC as children who are—

- orphaned

- separated from their parents

- living with caretakers with serious problems like illness, disabilities, trauma, substance addictions, abusive habits, or

- having normal families, but special needs that even well-functioning parents will need help to address (trauma, disability, behavioral problems).

The World Bank further defines OVC as children who, in a given local setting, are most likely to fall through the cracks of regular programs, policies, and traditional safety nets and therefore need to be given special attention when programs and policies are designed and implemented.

UNAIDS defines OVC much more narrowly, focusing only on orphans and defining them as children under 18 years of age whose mother, father, or both parents have died as a result of AIDS (United Nations, 2004).

The United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) defines OVC as children ages 0-17, who are either orphaned or made more vulnerable because of HIV and AIDS. PEPFAR defines a vulnerable child as one who is living in circumstances with high risks and whose prospects for continued growth and development are seriously impaired. According to PEPFAR, a child is more vulnerable because of any or all of the following factors that result from HIV and AIDS (The President's Coordinator 2006):

- is HIV positive

- lives without adequate adult support

- lives outside of family care, and/or

- is marginalized, stigmatized, or discriminated against.

For the purposes of this document, we examined programming under different definitions of OVC and of orphans, but used PEPFAR OVC categories to structure both the findings and recommendations (with the exception of including 5 year olds in the range of early childhood, as many SPRING's partners include children 2-5 in their early childhood activities).

1.1. A global perspective on the magnitude of the OVC problem

The estimated number of orphans, by all causes including AIDS, is reported yearly by agencies such as UNICEF. The varied way in which vulnerability is defined and measured across countries, however, makes the precise count of the world's total number of vulnerable children challenging. Approximations related to specific types of vulnerability attest to the magnitude of the global problem: 428 million children age 0–17 years live in extreme poverty, 150 million girls have experienced sexual abuse, 2 million children live in institutional care, and 218 million children engage in various forms of exploitative labor (Zosa-Feranil et al. 2010).

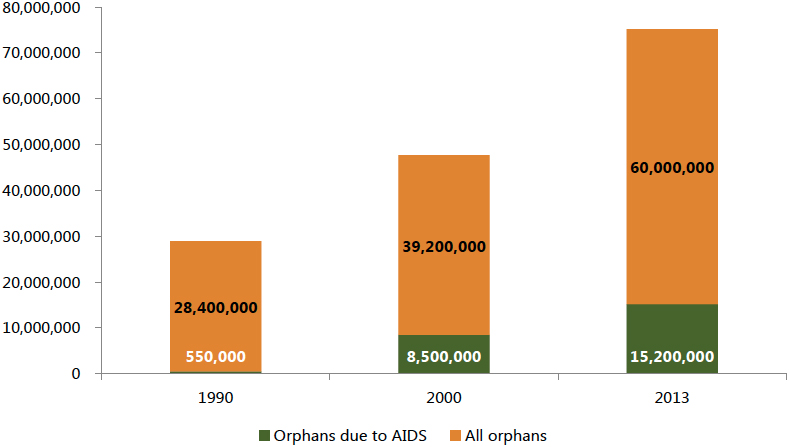

The most recent UNICEF estimates for the number of orphans (age 0–17 years) globally (referring to loss of one or both parents to all causes) is 140 million, with an estimated 17.7 million orphans attributed to AIDS. In SSA alone there are close to 60 million orphans, a number that represents more than 20 percent of all children in this region. An estimated 15.2 million children in SSA are orphaned due to AIDS (UNICEF 2013); this represents 86 percent of the global burden of orphans due to AIDS.

Graph 1. Orphans in sub-Saharan Africa: A Critical Concern

Source: UNICEF, Children and AIDS Stocktaking Reports, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2013

2. Magnitude of the OVC Problem in Nigeria

While HIV prevalence in Nigeria, at 3.2 percent, is lower than that in many other large countries in SSA, (UNAIDS 2014) its large population means the number of adults and children living with HIV is one of the highest in the world, at approximately 3,200,000 (National Agency for the Control of AIDS 2014). Furthermore, the orphan population in Nigeria is estimated to be 20 percent of the total SSA orphan population (AVERT n.d.).

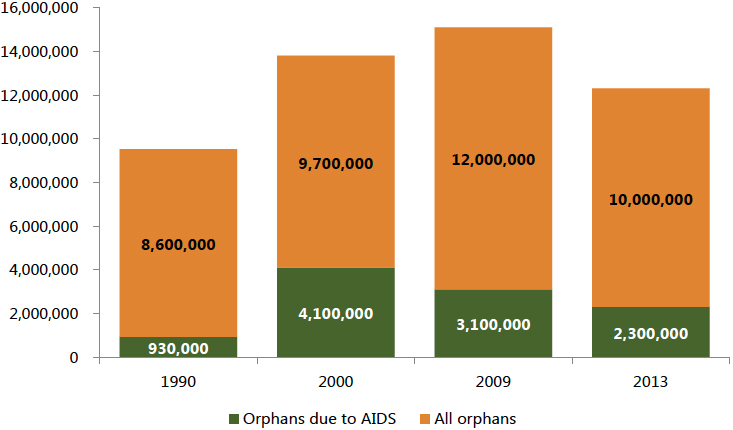

Although official counts vary, the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Women Affairs and Social Development (FMWASD) reported that there were 17.5 million OVC in 2008 (Tagurum et al. 2015). UNICEF reported 10 million Nigerian orphans due to all causes in 2013, with 2.3 million orphans due to AIDS, as well as 450,000 children and 180,000 adolescents actually living with HIV (UNICEF 2013). One study ranks Nigeria's OVC burden higher than several countries facing war, such as Sudan, Somalia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Libya, and Syria (Tagurum et al. 2015). One in every 10 households in the country is also estimated to be providing care for an orphan (Marsden and Miller 2011).

Graph 2. Orphans in Nigeria

Source: UNICEF Children and AIDS Stocktaking Reports, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2013

The 2013 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS)1 found that the percentage of orphaned children increases rapidly with age, from 4.2 percent among children under age five to 16.1 percent among children age 15-17. Data also indicate that urban children are slightly more likely to be orphaned than rural children (7 and 5 percent respectively). Among UGM project states, Benue had the highest number of OVC (16.4 percent), followed by Plateau (14.1 percent) and Nasarawa (13.8 percent). Table 1, which adapts the original NDHS data to show the states where UGM project partners STEER and SMILE are implementing programs, provides further explanation of these data.

A cross-sectional survey carried out in the Plateau State in 2014 revealed that paternal orphans made up 59.8 percent of respondents, followed by vulnerable children (21.7 percent) (Tagurum et al. 2015). This is similar to the situation in South Africa, where the majority of orphans have lost fathers (Bennell, Hyde, and Swainson 2002). Paternal orphanhood is significant because of the documented economic difficulties children face when they lose their fathers (Chirwa 2002, Abebe 2005).

Table 1. Nationally Representative Sample of OVC by Age, Sex, State and Partner Organization (National Population Commission, Federal Republic of Nigeria, and ICF International 2013).

| Characteristics | Number of Children | % of Children Who Are OVC |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Sex | ||

| Residence | ||

| SMILE | ||

| STEER | ||

| 0-4 | 30,108 | 4.2 |

| 5-9 | 28,849 | 7.9 |

| 10-14 | 21,691 | 11.8 |

| 15-17 | 9,790 | 16.1 |

| Male | 45,638 | 8.6 |

| Female | 44,796 | 8.3 |

| Urban | 33,812 | 9.4 |

| Rural | 56,626 | 7.9 |

| FCT-Abuja | 616 | 7.5 |

| Benue | 3,091 | 16.4 |

| Kogi | 1,509 | 12.3 |

| Nasarawa | 1,456 | 13.8 |

| Edo | 1,364 | 10.4 |

| Plateau | 1,490 | 14.1 |

| Bauchi | 3,404 | 10.7 |

| Kaduna | 4,653 | 4.8 |

| Kano | 8,704 | 5.7 |

| Sokoto | 2,961 | 4.9 |

Note: There are small discrepancies in some totals presented above. These data came from the NDHS and are reported in their original form.

3. Nigeria's Response to the OVC Crisis

Since 2004, the FMWASD has coordinated the national response to the OVC crisis, through the establishment of an OVC division and the development of a national priority agenda to assure and improve the quality of services provided for the well-being, protection, and development of children considered most vulnerable in Nigeria.

By 2007, Nigeria was one of 24 countries globally that had completed an action plan for OVC. The National Plan of Action (2006-2010) provided the framework for scaling up the national response to OVC in Nigeria. While the Nigerian Constitution defines an orphan as a child (0-17 years) who has lost one or both parents, the National Plan of Action provides a much more comprehensive and inclusive definition of OVC as highlighted in Table 2 below.

Table 2. Nigeria National Plan of Action Categorization of OVC (Nigeria OVC 2006)

| Children with physical and mental disabilities | Sexually abused children |

| Neglected children | Children in conflict with the law |

| Exploited "almajiri"2 | Child beggars, destitute children and scavengers |

| Children from broken homes, in which the parents have separated or divorced | Child sex workers |

| Children whose parents have a disability | Children who marry before the age of 18 |

| Children who have dropped out of school | Abandoned children |

| Children living with terminally or chronically ill parent(s) and caregiver(s) | Child laborers |

| Children in child-headed homes | Internally displaced children |

| Child hawkers | Trafficked children |

| Children of migrant workers such as fishermen, nomads | Children living with HIV |

| Children living with aged/frail grandparents |

The National Plan of Action identified the need for greater information and training resources focusing on nutritional care and management of OVC. To meet this objective, FMWASD developed a resource manual to provide detailed information on specific aspects of OVC nutrition. The FMWASD also developed the Psychosocial Care Training Manual, OVC Vulnerability Index Form, the OVC Advocacy Package and several other documents, highlighted in Table 3 (Biemba et al. 2009).

In 2007, FMWASD developed national guidelines and standards of practice for care of vulnerable children. These guidelines and standards focused on seven program areas, including food security and nutrition, with the aim of strengthening existing safety nets and providing additional resources without undermining the capacity of communities and families to care for and protect these children.

In 2014, FMWASD updated it national standards. These expanded the scope of OVC services beyond provision of direct support to individual children (e.g., school fees, health referrals) to comprehensive support to children, caregivers and households, and the community.

Table 3. Nigerian Policies, Strategies, Structures and Systems to Address OVC

| OVC division within FMWASD | National Steering Committee on OVC |

| OVC Stakeholders' Forum | National Plan of Action for OVC (2006-2010) |

| National OVC Monitoring and Evaluation Framework | OVC Eligibility Criteria Checklist |

| OVC Advocacy Package | Psychosocial Care Training Manual |

| Guidelines and Standards of Practice for OVC (2007)3 | OVC Vulnerability Index Form (2009)4 |

| Nutritional Care and Support for Vulnerable Children: A Resource Manual | National Standards for Improving the Quality of Life of Vulnerable Children (2014)5 |

Despite all of these efforts, it is estimated that ninety-five percent of OVC do not receive any type of medical, emotional, social, material or school-related assistance (National Population Commission, Federal Republic of Nigeria, and ICF International 2013).

4. Promising Interventions by Life Stage

Understanding the three different childhood life stages, the nutritional characteristics as well as the cognitive and emotional development associated with each life stage, and the venues and interventions recommended by USAID/PEPFAR (the major donor for OVC programming in Nigeria) for these life stages, is critical to determine the types of nutrition SBCC programming that may be most successful for this population.

As per guidance from PEPFAR, with the exception of the early childhood (which PEPFAR defines as 2 to 4 years) the ages and stages used in this document are defined as:

- Early childhood: 2 to 5 years old

- Middle childhood: 6 to 11 years old

- Late childhood: 12 to 17 years old

PEPFAR is advocating for OVC programming to improve children's and families' access to health and nutritional services through—

- a child-focused, family-centered approach to health and nutrition through early childhood development (ECD) and school-based programs

- effective integration with existing or planned child-focused community- and home-based activities, including prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT), treatment of HIV/AIDS, the President's Malaria Initiative, and child survival

- reduction of access barriers to health services through household economic strengthening (HES) and social protection schemes, such as health insurance opportunities

- establishment of linkages and referral systems between community- and clinic-based programs.

PEPFAR is also advocating the following venues and program interventions based on life stages, to serve as important conduits to general health information and services for children ages 2-17 and their families. These venues and program interventions have potential for nutrition-specific SBCC as well.

- Early childhood development programs provide an excellent venue for accomplishing multiple objectives, including nutritional education and supplementation, water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) promotion, early identification of childhood illness and developmental disabilities, and monitoring and support for children on treatment.

- Schools play a key role in health education and can also serve as an important channel for identifying and referring children who need further health and nutrition services and assistance.

- Kids' clubs that meet regularly and feature health messages in curricula have produced positive results. International research indicates that afterschool and other kids' clubs are most successful when they involve parents and caregivers. These clubs can provide an entry point for increasing knowledge and health-seeking behaviors, particularly for children who are not in school and are therefore missed by school-based health interventions.

- Parenting skills groups and education that facilitate child-caregiver bonding, and impart child development and positive discipline knowledge can play a key role in promoting basic health and nutritional knowledge.

- National or local health campaigns that focus on increasing coverage of key health and nutrition interventions should be leveraged for, and include, children affected and infected by HIV and AIDS. Such campaigns can utilize OVC community volunteers and build on other OVC program investments to enhance their success.

PEPFAR also supports the nutrition assessment, counseling, and support (NACS) framework (AIDSTAR-One 2012). This framework emerged from within the HIV and nutrition communities as a way to align interventions so that they work synergistically toward better nutrition and health outcomes for people of all age groups, including OVC.

Table 4 below outlines the three childhood life stages, including the nutritional characteristics, cognitive and emotional development, opportunities for nutrition SBCC programming during these periods, and recommended PEPFAR interventions. The table is a compilation of research performed by Michela and Contento in 1984, Singleton et al. in 1992, and Matheson et al. in 2002 on the role of food and nutrition, perceptions and experiences of children in early, middle and late childhood, nutritional and developmental characteristics of children as defined by Mitchell in 2008, and PEPFAR guidance for OVC programming (The President's Emergency Plan 2012). During early and middle childhood, there is a steady rate of growth and development, while puberty is a period of very rapid growth. Children and adolescents also have different cognitive and emotional development in these periods, and these differences have implications for the design of nutrition SBCC materials and programs, as well as the channels, timing, and location of interventions. See Annex 4 for detailed information on each life stage.

Table 4. Life Stages, Nutrition Characteristics, Cognitive/Emotional Development, and the Implications for Nutrition SBCC and OVC Programming (Mitchell 2008, Contento 2011, The President's Emergency Plan, 2012).

| Period | Approximate Years | Nutrition-related characteristics | Cognitive and emotional development | Implications for nutrition SBCC programming | OVC programs recommended by PEPFAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Late childhood | 12-17 | ||||

| Early childhood | 2-5 | - Slow, steady growth - Increased physical activity and coordination of motor functions - Rapid cognitive development | - Black and white thinking, reasoning limited to concrete objects - Criteria for food choice are specific and immediate - Trust and respect adults | - Conduct taste tests - Prepare foods - Design activities to engage the five senses | - Nutrition and ECD programs that boost holistic development - Age-appropriate entry into a safe, nondiscriminatory early learning program, especially for girls |

| Middle childhood | 6-11 | - Steady growth - Continued physical and cognitive development - Increasing responsibility for own food habits | - Black and white thinking, reasoning limited to concrete objects - Criteria for food choice are specific and immediate - Curious and motivated, enjoy experiments - Trust and respect for adults - Peer friendships increasingly important - Begin to desire autonomy | - Use characters and stories - Use active methods - Focus on functional meanings of food - Include handouts with bright pictures and direct messages - Foster self-esteem - Use simple goal-setting activities | - Access to education, enrollment in school and facilitation for retention - Child-friendly, gender-sensitive classrooms - Completion of primary school, especially for girls - Kids' clubs that develop social skills |

| Pre-puberty | - Accelerated growth rate - Rapid gains in weight and height - Changes in hormone levels, reproductive organs | - Criteria for food choice are specific and immediate - Relationships between food and health are becoming of interest - Trust and respect for adults - Anxious about peer relationships - Preoccupied with the body/body image and uncomfortable with the physical changes of puberty - Interested in immediate results | - Address benefits related to looking healthy, having more energy and/or performance in sports - Focus on short-term goals - Include handouts with bright pictures and direct messages - Use active methods | - Peer support groups - Protection from harmful labor/trafficking | |

| Puberty | - Development of secondary sex characteristics - Changes in body composition - Increased need for independence | - Abstract thinking still developing - Criteria for food choice becoming more complex, with increased reasoning about consequences - Greatly influenced by peers - Mistrustful of adults - Listen to peers more than adults - Consider independence very important - More in charge of the food they eat - Temporary rejection of family dietary patterns | - Design activities to analyze social influences, such as media, what is available in neighborhood stores or stores around schools, what their friends eat - Focus on how to make healthful choices - Use food demonstrations and taste tests - Use role playing | - Peer support groups | |

| Post-puberty | - Maximum gains in height - Continuing increases in bone mass - Cognitive development; increased independence | - Criteria for food choices become more complex, understand the notion of trade-offs - More established body image - Orientation to the future and making plans - =Increasingly independent - More consistent in their values and beliefs | - Build educational experiences around motivations that are particularly meaningful to this age group - Present dietary recommendations and give rationales - Focus on behaviors that adolescents have control over - Create homework-type assignments - Teach skills to address long-term goals - Provide food preparation experiences - Encourage decision-making skills | - Referrals to adolescent reproductive and family health services - Access to vocational education or other training opportunities that result in sustainable livelihoods for out-of-school youth - Mentorship programs | |

Note: The approximate years for girls and boys in the middle and late childhood stages are different because puberty begins at different times for girls than for boys. The peak of the growth spurt occurs at about age 12 for girls and age 14 for boys. Before this growth spurt there are no important differences between boys and girls in weight and height (Mitchell, 2008)

4.1. Venues and interventions in early childhood

Early childhood is the period in the life cycle considered most critical for the foundation of growth and development. Early childhood development is used to refer to the processes by which children grow and thrive physically, socially, emotionally, and cognitively during this time period, and ECD interventions are among the most cost-effective approaches for improving outcomes for vulnerable and at-risk children (Cunha and Heckman 2007). A review of ECD programs (Engle et al. 2007) demonstrate far-reaching benefits of early intervention for all children that lead to—

- reduced instances of stunting, heart disease, and mental illness

- increased school attendance

- improved social and gender equality, and

- enhanced prospects for income generation throughout life.

Despite this evidence, current OVC programming does not, for the most part, prioritize very young children (Dunn 2005) and U.S. government OVC resources largely focus on school-age OVC. Though some OVC programs include very young children in their activities, they rarely model their practices on ECD research or best practices, and they do not distinguish among the profoundly different stages marked by infancy, toddlerhood, preschool, and primary school.

In addition, there is no "one size fits all" approach to supporting ECD interventions for OVC. Some donors, CSOs or communities might prioritize providing basic child care so that caregivers can engage in income generating activities, while others might invest in education programs, the development of a child welfare committee that focuses on young children, or training staff at early childhood care centers to promote safety, early learning, and later school success. While working with community priorities is fundamental to ensuring the success of a program, all ECD interventions should address the core concepts of early child development, using evidence-based best practice interventions (AIDSTAR-One 2011).

When combined with daycare services, ECD centers have the potential to meet the growing demand for a safe and conducive environment for young children. Research reveals that access to ECD centers and services assists with brain development and can help overcome adverse experiences and toxic stress. These centers can also play a significant role in women's economic empowerment and girls' education. Orphaned and vulnerable children ECD programs that begin early by identifying pregnant women through PMTCT programs, and continue with "mom-baby pairs" to school entry can also serve as an excellent community- or household-based platform for achieving multiple maternal and child health (MCH) goals (AIDSTAR-One 2011).

Examples of OVC ECD venues, intervention and tools

Though there is little research on ECD interventions designed specifically for OVC or for high-prevalence HIV settings (AIDSTAR-One 2011), the following ECD interventions may demonstrate promise for adaptation and scale up in the Nigeria OVC context. The first example, CARE's 5 x 5 Model, focuses on reaching OVC in various childcare settings.

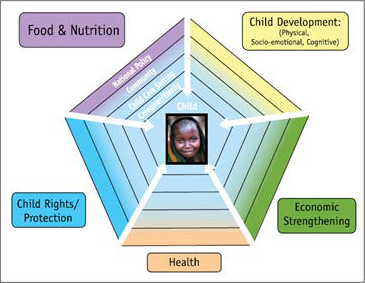

5 x 5 Model - CARE in Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Zambia, and South Africa

CARE's 5x5 Model (Promising Practices n.d.), which focuses on OVC and is currently operating in Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Zambia, and South Africa, identifies five areas of impact: 1) food and nutrition; 2) child development, including physical (gross and fine motor), cognitive (language and sensory), and socio-emotional (psychological and emotional); 3) economic strengthening; 4) health; and 5) child rights and protection. The childcare setting—from crèche to formal school—is the entry point for all interventions.

In 2006, CARE established a comprehensive ECD program at a center in Busia, a town along a transport corridor in Uganda. At this center, children ages 2-8 are provided with a stimulating, healthy child care environment and nutritious daily meals, while complementary programming reaches out to the community to create a conducive environment for child development. The project informs the community about child nutrition, parenting skills, and child rights through regular radio programming. This has led to increased demand for ECD services.

A local Catholic health center provides preventive and curative medical services to children and their families, while older OVC, who are often heads of households in Uganda, are referred to area vocational schools for skill training. The ECD center is linked with a government child welfare officer to address issues related to child rights violations and enforcement. Microfinance programming helps caregivers, many of whom are grandparents, to access low interest loans and establish microenterprises. The center has also established a mothers' mentoring program in which young mothers are paired with older mothers to enhance their parenting skills and access much needed support.

Another example comes from PATH, which reaches children during the early years through a variety of activities at the community and facility levels.

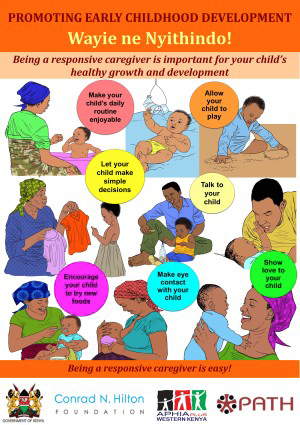

Early Childhood Development Package – PATH in Kenya and Mozambique

In the first years of a child's life, the health system at both the facility and community level represents the best, and often only, way to reach young children and their caregivers. Since 2011 and with funding from the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation and BHP Billiton Sustainable Communities, PATH has piloted and assessed approaches to integrate child care and stimulation content into community- and facility-level services delivered by both community-based organizations (CBOs) and government health systems in Kenya and Mozambique.

PATH's approach to integrated ECD involves integrating age-appropriate care and stimulation messages and activities into MCH service delivery points, and targeting children and their caregivers from conception to a child's third birthday. PATH has adopted Module One (Care for Child Development) of the Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses approach (World Health Organization n.d.), as its principle ECD capacity building tool. PATH's ECD themes typically include facility-based health and nutrition counseling, antenatal care, postnatal care, growth monitoring and promotion, routine immunizations, PMTCT, community support groups (such as mothers' support groups), home visits by community health workers, and other services offered by CBOs. PATH has developed a series of colorful graphic posters and counseling cards on ECD for use by health facilities and communities. The health facility cards present recommended ECD actions appropriate for each theme, while community cards are organized around phases such as pregnancy and the first six months, and provide discussion questions and key messages.

The Essential Package, a collaboration between CARE, Save the Children, and others, is a holistic approach to support OVC and their caregivers through interventions appropriate to age and developmental stage.

The Essential Package - CARE, Save the Children and the Consultative Group on Early Childhood Care and Development

The Essential Package consists of four main components: (1) a 'Framework for Action' document for policy makers and program managers; (2) an in-depth literature review which provides the rationale for mainstreaming ECD into OVC programming; (3) frameworks that highlight the needs of young children and their caregivers and provide essential actions to address identified needs; and (4) a toolkit to support the frameworks. The goal of this work is to empower volunteers, home-based care providers and other paraprofessionals at the point of service delivery to assess the needs of a household, provide targeted messages to enhance caregiver-child interaction, and link families to systems of care to meet needs.

4.2. Venues and interventions in middle childhood

While children in the middle childhood period (sometimes referred to as the primary school period and/or pre-adolescence) share the same needs for housing, social support, and education as their younger counterparts, they face key developmental milestones which may be particularly challenging for those who are vulnerable. While the physical size of a child increases steadily, the ways in which the child thinks (intellectual growth), feels about things (emotional growth), and interacts with other children and adults (social growth) all develop much more rapidly.

Examples of OVC middle childhood venues, intervention and tools

A compelling example for middle childhood programming is UNICEF's Getting Ready for School pilot program, collaboration between UNICEF and the Child to Child Trust at the Institute of Education, University of London (UNICEF Evaluation Office 2012). Bangladesh, China, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Tajikistan and Yemen participated in the pilot, which was unique in its child-to-child approach, with older children (called young facilitators) working with younger peers to increase their academic and non-academic school readiness skills.

Getting Ready for School: A Child-to-Child Approach - UNICEF

Getting Ready for School is an innovative and cost-effective way to prepare young children and their families to enroll in school on time and to succeed once enrolled. Recognizing the lack of formal preschools and other early learning opportunities for most children in developing countries, this strategy – which supplements other early learning opportunities – builds on the natural phenomenon of younger children learning from, and interacting with, older children. The pilot program trained young facilitators (older schoolchildren typically in grades 4-8), as well as teachers who provided guidance and supervision to young facilitators. Young facilitators then engaged young children in the community who were one year away from expected on-time school entry. Young facilitators and young children met in sessions that were typically held twice weekly at a school or in the community, and engaged in a series of planned activities designed to support child development through play. The guides for teachers and young facilitators contain storybooks, puzzles, picture and word count games, as well as activities that help children tell and retell stories, make puppets, draw and color, and recognize letters in their name. There are five activity sets, each with multiple sessions.

School principals reported increased levels of school-community interaction, high levels of satisfaction with the program among school staff, and increased understanding of young children's development among teachers. Teachers and young facilitators rated nearly all of the activities as enjoyable for the children.

Another example is the USAID Yaajeende project, a five-year Feed the Future activity designed to reduce malnutrition in Eastern Senegal.

NCBA CLUSA/Yaajeende's "Manger comme un Champion" School Notebooks – USAID in Senegal

To educate students about how to recognize and overcome key nutritional deficiencies, the USAID-funded Yaajeende project, implemented by NCBA CLUSA, designed "Manger comme un Champion" notebooks for primary school students with educational inserts and visual images. The project distributed more than 90,000 notebooks and conducted complementary in-class activities. These notebooks were effective not only in reaching students with key messages, but also reaching their families. The project also developed games modeled on the game "Ludo" as an educational tool to educate women about exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding.

School- and community-based peer and social group interventions through youth clubs are also a strategy to promote proper nutrition. Such spaces often provide psychosocial support, along with age-appropriate learning materials focusing on multiple health issues. Staff can address topics of concern to OVC through plays, poems, stories, games, and interactive group therapy techniques, including approaches to problem solving and positive deviance. Triple Play, a Boys & Girls Club program in the United States, is one such program.

Triple Play - Boys & Girls Clubs in the United States

Triple Play is a dynamic wellness program targeting primary school children that is currently offered at Boys & Girls Clubs in the United States. The program demonstrates how eating right, keeping fit and forming positive relationships add up to a healthy lifestyle. The goal of the program is to improve club members' knowledge of healthy habits; increase the number of hours per day that they participate in physical activities; and strengthen their ability to interact positively with others and engage in positive relationships. An impact evaluation performed in 2009 found that "Triple Play" improved youth nutrition knowledge (Gambone et al. 2009).

Finally, the Community Care program in Nigeria, which was implemented through 2011, focused on strengthening community and household structures to respond to the needs of women affected by HIV and AIDS, and mitigating the impact of HIV on households' ability to care for OVC. The program reported that OVC attending kids' clubs associated with the program were more confident and that 70 percent of the children attending primary school improved their grades (Biemba, Walker and Simon 2009).

4.3. Venues and interventions in late childhood

The remarkable growth that occurs during late childhood creates increased demands for energy and nutrients. Total nutrient needs are higher during adolescence than any other time in the lifecycle and at the peak of the adolescent growth spurt, nutritional requirements may be twice as high as those of the remaining period of adolescence (Mitchell 2008). Failure to consume an adequate diet during this time can result in delayed sexual maturation and can arrest or slow growth.

Prior to puberty, nutrient needs are similar for boys and girls but biological changes during adolescence create specific nutrient needs for girls and boys. It is therefore important that community programs, peer education, and health services addressing the needs of vulnerable adolescents deliver services through sex- and age-appropriate interventions.

Examples of OVC late childhood venues, intervention and tools

A promising example is the Teen Club program in Botswana, which reported meeting multiple objectives including improved clinical outcomes for treatment of HIV among adolescents. These venues reach OVC and could incorporate nutritional messaging and programming.

Teen Club: Peer Support for HIV-positive Adolescents – Botswana

In 2005, the first Teen Club for HIV-positive adolescents in Botswana began at the Botswana-Baylor Children's Clinical Centre of Excellence. The mission of Teen Club is "to empower HIV-positive adolescents to build positive relationships, improve their self-esteem and acquire life skills through peer mentorship, adult role-modelling and structured activities, ultimately leading to improved clinical and mental health outcomes as well as a healthy transition into adulthood." Teen Club currently has over 450 active members and attendance is increasing every month. Teen Club events typically occur on Saturdays and have included large group games, drama activities, pool parties, safaris, movie nights, and art sessions. Since 2008, Teen Club has expanded to five satellite sites throughout Botswana through innovative partnerships with local anti-retroviral clinics and CBOs, with plans to roll out the support group to even more satellite sites in the near future. The Teen Club model has been replicated in Lesotho, Swaziland, Malawi, Uganda and Tanzania, making Teen Club the largest network of peer support groups for HIV-positive adolescents in the world.

Another strategy is creating dedicated social spaces for girls, which is a key for changing girls' self-concepts and a proven approach for transforming the very circumstances that put girls at risk for acquiring HIV. These spaces, which can be established inexpensively at community facilities like schools (after hours) and community centers, can function as platforms for the delivery of new skills, increased social support, and greater opportunities for girls. Vulnerable girls and young women gather regularly at these spaces to meet peers, consult with mentors, and acquire skills to help them head off or mitigate crises (e.g., threats of marriage, leaving school, or forced sex).

Examples include the Girls' Café program in Mozambique, the Girls on the Run program in the United States, the Girl Guides/Scouts, Anemia Prevention Badge Program in East and Southern Africa, and the Adolescent Anemia Prevention Project in Egypt.

Girls' Café – Mozambique

A Christian organization called Tearfund (funded by DFID) introduced a Girls' Café for young women ages 12-25 to promote gender equality, reduce girls and young women's vulnerability to HIV, raise girls' self-esteem and empower them to make decisions about their sexuality. The Girls' Café provides a safe place for 80-95 girls from poor households to meet bi-weekly and engage in a curriculum-based discussion around issues of identity, sexuality, reproductive health, abuse, masculinity and femininity in traditional and modern society. The Girls' Café is peer led and includes social fellowship while sharing a meal together. Female role models mentor the group and share their lives and experiences. An internal evaluation found a positive impact on self-esteem; 80 percent of girls passed their class exams compared with 50 percent previously, and 80 percent of the girls reported that they felt more confident in speaking to their parents about life issues.

Girls on the Run® – United States

Meeting twice a week in small teams of 8-20 girls, this program teaches life skills through fun, engaging lessons that celebrate the joy of movement. The 24-lesson curriculum is taught by certified Girls on the Run® coaches and includes three parts: understanding ourselves; valuing relationships and teamwork; and understanding how we connect with and shape the world at large. Over the course of the program, girls develop and improve competence, feel confidence in who they are, develop strength of character, respond to others and oneself with care and compassion, create positive connections with peers and adults, and make a meaningful contribution to their communities and to society. A pilot assessment performed in 2002 in five geographic areas showed improvements were statistically significant for self-esteem, eating attitudes and behaviors, and body size satisfaction (Girls on the Run "National Evaluation"2002).

Anemia Prevention Badge Program – Girl Guides in Uganda, Rwanda and Swaziland

The Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA) project, the Regional Center for Quality Health Care (RCQHC) and the African Regional Office of the World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts worked together to expand coverage of anemia intervention packages in East and Southern Africa through a program to reach adolescent girls in Uganda, Rwanda and Swaziland. Girl Guides can earn a badge in anemia prevention through educational programs and community involvement in anemia control. FANTA developed the Anemia Prevention Badge materials, including the Guiders' manual, handbook and workbook. FANTA, RCQHC and the Uganda Girl Guides Association then conducted a qualitative assessment of the program in Uganda. An assessment report discussed Girl Guides' experiences in the program, including knowledge gained, community outreach, practical exercises performed to earn the badge, and what anemia prevention behaviors they currently practice. Over 4,000 Girl Guides participated in the program in Rwanda, Swaziland and Uganda, and Girl Guides reached 7,500 adolescent peers, parents and community members through presentations, performances, drama and dance.

Website | An Assessment of USAID’s Programs and Policies to Improve the Lives of Women and Girls

While not specific to girls, another anemia prevention project also shows promise as a platform for nutrition SBCC.

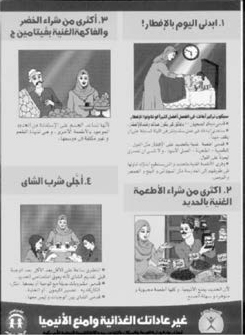

Adolescent Anemia Prevention Program – Egypt

A survey of adolescents in Egypt estimated that 50 percent of adolescent girls and boys are anemic. To address adolescent anemia, the Egyptian government and the Student Health Insurance Program began a targeted program to lower those rates through a dynamic school-based program, implemented by JSI and The Manoff Group. The program adopted a two-pronged strategic approach—supplementation and nutrition education. Supplementation included weekly in-school provision of iron supplements, while poor dietary habits were addressed through targeted communications activities to increase dietary intake of iron-rich foods. The media aired radio and television spots (free on local government channels) to inform community members, parents and students about the program. These spots started a month before the program began in schools and continued throughout the year. The program distributed formal educational materials to students and to parents of younger students, hung posters in the schools, and developed materials for use by nutrition educators in the school system. For preparatory and secondary students, the program designed a colorful booklet containing interactive stories, word games, and puzzles based on information about anemia and key behaviors to prevent it. Activities were developed that required no materials or teaching aides—for example, playing games based on information about anemia or creating a soap opera (about the tragedy of the star having anemia and how it affects her life). Results showed a 20 percent decline in anemia among tested students.

Shakthi is a social media platform specifically designed for youth and a potentially appropriate venue to address nutrition.

Youth Engagement Platform - Shakthi

Shakthi provides young people with the opportunity to become members of a network, connect with their peers, join special interest or topical groups, and post messages to the network much like other social media platforms. In addition, Shakthi enables an organization to create a community of purpose meant to fulfill specific program outcomes and project goals. Shakthi has built a system that emphasizes fun and playfulness as an integral part of the learning process. Borrowing elements from video games, the platform facilitates contests, awards, and level-ups using badges.

Other strategies involve livelihood, vocational and/or income-generating activities, such as training youth and OVC caregivers in community video and sustainable agricultural methods. Three examples of such programs are below.

Junior Farmer Field and Life Skills – Mozambique

Junior Farmer Field and Life Skills (JFFLS) is one of 20 food security and nutrition interventions recommended by PEPFAR for OVC (Greenblott and Nzinga International 2012). This program provides agricultural and life skills to OVC and seeks to improve the livelihoods of vulnerable boys and girls and provide them with future opportunities while minimizing the risk of adopting negative coping behaviors. The JFFLS approach is based on an experiential learning process that encourages the group to observe, draw conclusions, and make informed decisions consistent with good agricultural and life practices. Using this approach enables OVC to understand how knowledge and life skills can change their attitude about their lives while understanding how to grow crops. Training can be delivered as part of a school or after-school curriculum, or via church or youth CBOs. Training content includes establishment of kitchen gardens, multiple story and container gardens, food preservation and preparation techniques, organic farming and agro-forestry. Caregivers are taught how to use local diets to maximize nutrition consumption, particularly for children and those living with HIV, and are supported to initiate improved food production techniques. A JFFLS project of note, initiated in 2003, was introduced as a pilot project in one urban and three rural faith-based organizations' "open centers" in Mozambique. The direct beneficiaries were approximately 100 children attending the open centers. Children were selected based on being maternal or paternal orphans regardless of the cause of death of the parent, being ages 12-18 years, and being a local resident. This program has since then been adapted and tested in Zimbabwe, Kenya, Swaziland, and Namibia.

Vocational Training and Income-Generating Activities – Colombia

Vocational training is also recommended by PEPFAR for OVC (Greenblott and Nzinga International 2012). The Jóvenes en Acción vocational training program in Colombia provided OVC and caregivers with marketable skills and income generating potential in their communities. The goal was to increase individuals' chances of developing a viable livelihood and long-term food security. Vocational training curricula were delivered via home-based care, after-school programs, support and self-help groups for people living with HIV, youth groups, community groups, and private-public partnerships. A comprehensive market survey was a mandatory part of any vocational training/income-generating activity, which helped ensure that youth could acquire jobs and/or viable income-generating opportunities upon graduation from the training. The program provided three months of in-classroom training and three months of on-the-job training, and reached 80,000 young people (approximately 50 percent of the target population). Comparisons between those offered and not offered training showed that those offered training fared better in the labor market and were more likely to be employed. In particular, being offered training increased paid employment by about 6.8 percent.

Community Video and Facilitated Discussion to Engage Youth and Improve Nutrition – Niger and India

Since 2012, SPRING has collaborated with Digital Green (DG), to promote key maternal, infant, and young child nutrition and hygiene-related behaviors through a digital learning approach. Building on lessons learned from the initial collaboration, SPRING and DG began adapting the digital platform to promote nutrition and food security in the Sahel, including for adolescent girls. In this highly vulnerable setting, SPRING and DG have worked to build local NGO capacity to develop video content based on community-identified priorities and facilitate the dissemination of ten videos.

Recommended Menu of OVC Nutrition Social and Behavior Change Communication Options

After reviewing many strategies and activities, SPRING recommends the following menu of options.

| Life stage | Recommended menu of options |

|---|---|

| Early childhood: Ages 2 - 5 | 1. Adapt PATH's early childhood development (ECD) Package materials from Kenya and Mozambique (counseling cards, group session cards, posters and toy kits) with age appropriate nutrition messages and activities. 2. Adapt materials from the Essential Package created by CARE, Save the Children and the Consultative Group on ECD with age appropriate nutrition messages and activities. |

| Middle childhood: Ages 6 - 11 | 1. Adapt the NCBA CLUSA Yaajeende school notebooks and nutrition-focused game(s) for students. 2. Adapt the "Getting Ready for School: A Child-to-Child Approach" teaching materials such as the guides for teachers and young facilitators, and thematic flyers with age appropriate nutrition messages and activities. 3. Create easy-to-read booklets and comics with nutrition-specific SBCC information. |

| Late childhood: Ages 12 -17 | 1. Reach out to community and regional radio programs to train adolescents to create radio jingles with nutrition messaging and pre-developed audio material with Q & As. 2. Use Shakthi or another youth engagement platform such as Facebook, WhatsApp or 2go to send out tips, advice and guidance on proper nutrition. 3. Use mobile technology to send out a SMS of the day/weeksuch as "Family Nutrition 101" 4. Adapt the Boys & Girls Club "Triple Play" in after-school sports programs, focusing on improving the overall health of OVC by increasing their daily physical activity, teaching them good nutrition, and helping them develop healthy relationships. 5. Adapt SPRING's work with DG to support youth to develop videos with nutrition messaging that can be shared and transferred to DVDs and/or audio on SIM cards. (Strengthening Partnerships 2013). |

Conclusion

Given its importance in the realization of sustainable improvements, SBCC is a key element of SPRING's approach to improving nutrition. Based on a review of global and Nigeria-focused research as well as results of survey conducted among CSOs working with the UGM OVC Project, this review presents recommendations for adapting existing nutrition-focused SBCC interventions for use in OVC nutrition programming in Nigeria. All recommended programs and activities have demonstrated their effectiveness and all have strong potential for engaging OVC populations and their caregivers. Moving forward, SPRING/Nigeria will work with the management and technical teams from STEER and SMILE, as well as with their participating CSOs, to identify the most appropriate programs and activities for their target populations, present those recommendations to USAID, and develop workplans and a robust set of indicators to track design and implementation processes as well as the impact of the programming on OVC and their caregivers.

Footnotes

1 The survey included only orphans and vulnerable children living in households. The results do not include children who are living in institutions or other non-household settings.

2 Almajiri are Qur'anic students who live under the custody of teachers along with other almajiri. Though under a teacher’s custody, a teacher does not feed his almajiri and some expect their students to bring food to his family. Hence, almajiri have to beg for food.

3 These were designed as an emergency response to the HIV and AIDS epidemic and focused on the provision of direct services to individual children rather than to families or communities.

4 This is a targeting tool to identify children in need of services.

5 These standards encourage family-centered interventions at the household level rather than handing out materials to identified “vulnerable” children.

References

Abebe, T. 2005. “Geographical dimensions of AIDS orphanhood in sub-Saharan Africa.” Norwegian Journal of Geography, 1.

AIDSTAR-One. 2011. “Early childhood development for orphans and vulnerable children: Key considerations. Technical Brief.” AIDSTAR-One (now AIDSFree) website.

AIDSTAR-One. 2012 “The Debilitating Cycle of HIV, Food Insecurity, and Malnutrition Including a Menu of Common Food Security and Nutrition Interventions for orphans and vulnerable children.” AIDSTAR-One (now AIDSFree) website.

Appropriate IT. “Home Page.” Appropriate IT website.

AVERT. “Key Affected Populations: Children and HIV/AIDS.” AVERT website.

Bennell, Paul, Karin Hyde, and Nicola Swainson. The Impact of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic on the Education Sector in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Synthesis of the Findings and Recommendations of Three Country Studies. Brighton Centre for International Education, University of Sussex, 2002.

Biemba, Godfrey, Mary Ebunlomo Walker, MBChB, Jonathon Simon. “Nigeria Research Situation Analysis on Orphans and Other Vulnerable Children Final Report 2009.” Boston University website.

Blackett-Dibinga, Kendra et al. “The Essential Package Holistically Addressing the Needs of Young Vulnerable Children and Their Caregivers Affected by HIV and AIDS.“ CARE website.

Boys & Girls Clubs of America. “TriplePlayDetail.” The Official Site of Boys & Girls Clubs of America.

C-Change. 2012. “Overarching Communication Strategy for Programs in Family Planning, Maternal Child Health, Nutrition, HIV/AIDS & Education in Guatemalan Western Highlands.” C-Hub website.

Chirwa, W.C. 2002. “Social exclusion and inclusion: challenges to orphan care in Malawi” Nordic Journal of African Studies, 2.

Contento, Isobel R. 2011. Nutrition Education: Linking Research, Theory, and Practice. 2nd Ed. Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Cunha, Flavio and James Heckman. 2007. “The Technology of Skill Formation, Working Paper 12840.” National Bureau of Economic Research website.

Dunn, A. HIV/AIDS: What About Very Young Children? The Hague, The Netherlands: Bernard van Leer Foundation. 2005.

Elkind, David. 1998. All Grown up & No Place to Go: Teenagers in Crisis. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

Ene-Obong, Henrietta, et al. 2012. Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Thinness among Urban School-aged Children and Adolescents in Southern Nigeria. Food & Nutrition Bulletin 33, no. 4.

Engle, Patrice L. et al. 2007. “Strategies to avoid the loss of developmental potential in more than 200 million children in the developing world.” The Lancet, 369.

The Federal Republic of Nigeria, and National Bureau of Statistics. “LSMS – Integrated Surveys on Agriculture General Household Survey Panel 2012/2013. A Report by the National Bureau of Statistics in Collaboration with the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development and the World Bank.”

Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project. 2007. “Girl Guides Anemia Prevention Badge Project.” Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project website.

Gambone, Michelle Alberti et al. 2009. “Promoting Healthy Lifestyles: The Impact of Boys & Girls Clubs of America’s Triple Play Program on Healthy Eating, Exercise Patterns, and Developmental Outcomes (Executive Summary).” Philadelphia: Youth Development Strategies, Inc.

Gillespie, Stuart. 2006. “AIDS, poverty, and hunger: Challenges and responses. Highlights of the International Conference on HIV/AIDS and Food and Nutrition Security, Durban, South Africa, April 14–16, 2005.”

Girls on the Run. “What We Do.” Girls on the Run website.

Girls on the Run. “National Evaluation.” Girls on the Run website.

Greenblott, Kara, and Nzinga International. 2012. “The Debilitating Cycle of HIV, Food Insecurity, and Malnutrition: Including a Menu of Common Food Security and Nutrition Interventions for Orphans and Vulnerable Children. USAID’s AIDS Support and Technical Assistance Resources, AIDSTAROne, Task Order 1.

Koniz-Booher, Peggy et al. 2013. "Community-Led Formative Research to Determine Priority Nutrition Behaviors for an Innovative Participatory Video Feasibility Study." USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally website.

Ladipo, Sunday Olusola, and Adewale Adeduntan. "Access to Media Resources as Predictor of Adolescents’ Attitude to Sexual and Reproductive Health Practices in Selected Non-Governmental Organisations in Nigeria." Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Paper 858 (2012).

Lamstein, Sascha et al. 2014. “Evidence of Effective Approaches to Social and Behavior Change Communication for Preventing and Reducing Stunting and Anemia: Report from a Systematic Literature Review.” USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally website.

Marsden, Paul and Laura Guyer-Miller. 2011. “Social Welfare Workforce Strengthening for Orphans and Vulnerable Children (OVC) Care, Support and Protection in Nigeria CapacityPlus Scoping Visit Report.” OVCupport.net website.

Mitchell, Mary Kay. 2008. Nutrition across the Life Span. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders.

National Agency for the Control of AIDS. 2014. “Federal Republic of Nigeria Global AIDS Response Country Progress Report 2014.” UNAIDS website.

The National Cooperative Business Association CLUSA International. “Project Profile: USAID/Yaajeende Agriculture And Nutrition Development Program For Food Security In Senegal.” The National Cooperative Business Association CLUSA International website.

National Population Commission, Federal Republic of Nigeria, and ICF International. "Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey, 2013." The DHS Program website.

“Nigeria OVC National Plan of Action.” The African Child Policy Forum website.

“Nutritional Care and Support for Vulnerable Children: A Resource Manual.” USAID's Infant & Young Child Nutrition Project website.

Onyiriuka, Alphonsus N, Amarabia N Ibeawuchi, and Rita C Onyiriuka. 2013. Assessment of Eating Habits among Adolescent Nigerian Urban Secondary Schoolgirls. Sri Lanka J Child Health Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health 42, 1.

PATH Maternal and Child Health and Nutrition Global Program. “An Update on PATH’s Early Childhood Development Work.” PATH website.

Promising Practices. “Promoting Early Childhood Development for OVC in Resource Constrained Settings: The 5x5 Model.” Program Quality Digital Library website.

Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally. “SPRING and Digital Green Feasibility Study in India.” 2013. USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally website.

Taurum, Yo, et al. 2015. Situational Analysis of Orphans and Vulnerable Children in Urban and Rural Communities of Plateau State. Ann Afr Med Annals of African Medicine 14, 1.

The Manoff Group. “Egypt: Preventing and Treating Anemia in School Children.” The Manoff Group website.

The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief Office of the U.S. Global AIDS. 2012. “Guidance For Orphans And Vulnerable Children Programming.” The PEPFAR website.

The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator. 2006. “Orphans and Other Vulnerable Children Programming Guidance for United States Government In-Country Staff and Implementing Partners.” The PEPFAR website.

Udanyi, Rhoda E. et al. 2008. Peculiar Vulnerability Factors of OVC and their Caregivers in Nigeria. ResearchGate website.

UNAIDS. “Nigeria: HIV and AIDS estimates (2014).” UNAIDS website.

UNICEF. 2013. “Towards an AIDS-Free Generation Children and AIDS: Sixth Stocktaking Report 2013.” UNICEF website.

UNICEF. 2010. “Children and AIDS: Fifth Stocktaking Report, 2010.” UNICEF website.

UNICEF. 2009. “Children and AIDS: Fourth Stocktaking Report 2009.” UNICEF website.

UNICEF. 2008. “Children and AIDS: Third Stocktaking Report 2008.” UNICEF website.

UNICEF. 2007. “Children and AIDS: A Stocktaking Report 2007.” UNICEF website.

UNICEF ESARO. 2011.“Children and AIDS Regional Initiative, Botswana Teen Club.” UNICEF ESARO website.

UNICEF Evaluation Office. 2012. “Getting Ready for School: A Child-to-Child Approach, Programme Evaluation for Year One Grade One Outcomes.” UNICEF website.

United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, United Nations Children's Fund, and United States Agency for International Development. 2004. “Children on the Brink 2004.” UNICEF website.

USAID/ Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally. “The SPRING/Digital Green Collaboration.” USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally website.

van Liere, Marti et al. 2014. “Designing the Future of Nutrition Social and Behavior Change Communication: How to Achieve Impact at Scale.” USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally website.

World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts, Africa Region. “The Anaemia Prevention Badge Guiders’ Training Manual.” FANTA project website.

World Bank Africa Region, and World Bank Institute. 2005. “The OVC Toolkit for SSA.” World Bank website.

Women's Learning Partnership. “Essay Contest Finalists: Group 1, Ages 14-18.” Women's Learning Partnership website.

Women's Learning Partnership. “UDHR YouTube Competition.” Women's Learning Partnership website.

World Health Organization. “Integrated Management of Childhood Illness.) World Health Organization website.

Zosa-Feranil, I., A. Monahan, A. Kay, and A. Krishna. 2010. “Review of Orphans and Vulnerable Children (OVC) in HIV/AIDS Grants Awarded by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Rounds 1–7).” Futures Group, Health Policy Initiative, Task Order 1. 2010.

Appendices

To view the appendices, please download the file at the top of this page.