UPAVAN Formative Research Report

Executive Summary

Introduction

There is growing recognition in the nutrition community that, to effectively address undernutrition, interventions must go beyond addressing the immediate (nutrition-specific) causes of undernutrition, such as breastfeeding and dietary diversity, to also address underlying (nutrition-sensitive) determinants of undernutrition, such as agriculture and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) (USAID 2014). As such, funders and program implementers are exploring ways in which programs in nutrition-related sectors, such as agriculture, can increase the “nutrition-sensitivity” of their interventions to positively impact nutrition outcomes. However, evidence around effective nutrition-sensitive agriculture approaches is limited. As an adaptable, participatory approach, community video is a promising intervention to increase nutrition-sensitivity within agricultural programs by delivering both nutrition-sensitive agriculture and nutrition-specific MIYCN and hygiene content.

The formative research presented in this report was conducted as part of the Upscaling Participation and Videos for Agriculture and Nutrition (UPAVAN) project, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) testing the effectiveness of a community video model for improving nutrition and agriculture outcomes. The study was conducted in rural Odisha, India, where seasonal food insecurity, as well as sub-optimal diet, health care, and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) practices, contribute to high rates of undernutrition. UPAVAN is led by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), with partners Digital Green (DG), the Voluntary Association for Rural Reconstruction and Appropriate Technology (VARRAT), Ekjut, University College London (UCL), and JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc. The SPRING project provides additional technical support to the partnership and led a formative research process to explore drivers of food choice, farming, diet, WASH, and care practices among farming households. In the community video model, partners train and support agriculture and health workers to promote improved agriculture and nutrition practices by producing and discussing community-made videos at monthly women’s group meetings.

The findings of the formative research informed three key outcomes:

- Recommendations for nutrition-specific MIYCN/hygiene and nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices to promote in community videos. Social and behavior change (SBC) interventions such as this are more effective if they promote a limited number of practices (Lamstein et al. 2014). SPRING and its partners used formative research findings to identify a limited number of priority crops and livestock to promote throughout the intervention, as well as appropriate nutrition-sensitive agriculture and nutrition-specific MIYCN practices.

- Recommendations of key crops and foods to feature in community videos and to promote for cultivation and sale or consumption, based on nutrient content and community members’ perceptions of availability, affordability, tastiness, and healthfulness.

- Revisions to an existing MIYCN/hygiene training package, and the creation of a nutrition-sensitive agriculture training for community-level video production teams and extension workers. These training packages were adapted to the findings of the formative research and prioritized practices, and aimed to provide sufficient technical background for UPAVAN teams to produce videos and effectively mediate community video disseminations throughout the intervention.

By focusing project resources on promoting practices identified through a systematic, evidence-based process, we will increase the likelihood that project interventions will lead to sustained change among a significant portion of the population, contributing to better nutrition and health in UPAVAN’s implementation area.

Findings and Recommendations

SPRING learned which foods communities perceived positively, and which foods were considered expensive or harmful. There was broad consensus with slight variation based on market access and very localized food taboos. SPRING and project implementers used these findings to determine priority crops/livestock to promote for production, consumption, and sale; and priority foods to promote for consumption. Relevant context appropriate nutrition-sensitive agriculture interventions include, for example, safely intensifying production, improving post-harvest processing and storage, or prioritizing purchase of desirable and healthful foods.

We also learned how respondents think about gender roles, decision-making about health care or money, and what their ideals are about successful farming or good family relationships. For example, the ideal of a “good relationship” between a mother-in-law and a daughter-in-law and between a husband and wife includes “friendly” communication, task sharing for food preparation and childcare, and joint decision-making about finances, agriculture, and festival observations (a year round issue affecting spending and diet decisions).

Findings related to women’s empowerment were key to designing interventions promoting additional rest and less heavy work for pregnant women and increasing women’s participation in farm and household decision-making. As these practices fit well within existing norms and family roles, they are more likely to be adopted, and thus more likely to contribute to nutrition. For example, respondents stated that husbands and grandmothers have important roles in caring for pregnant women and that pregnant women should work less and refrain from heavy tasks.

The research findings presented in this report have been used to help prioritize crops/livestock, foods, and nutrition-specific MIYCN and nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices to promote, but they can also continue to inform how UPAVAN frames key messages about the practices highlighted in community-made videos. For example, findings indicate that communities may be responsive to supporting additional rest and less heavy work for pregnant women; sharing childcare tasks; and increasing women’s participation in farm and household decision-making, because all of these practices fit within their existing beliefs and attitudes. Concrete data from direct observations and secondary data about nutritional content of local foods complemented the more abstract data about respondents’ behavioral ideals, which allowed SPRING and partners to confidently set priorities on which MIYCN, agriculture, and nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices to promote.

1. Background

1.1 Overview of UPAVAN

By combining the power of traditional storytelling with low-cost technology, the SPRING project and Digital Green (DG) have developed a community video social and behavior change (SBC) approach to improve maternal and child health and nutrition outcomes. DG first began using community video as a tool for agriculture extension in India, demonstrating improved farming techniques through videos made by local farmers and agriculture extension workers. In 2013, SPRING and DG first tested the feasibility of this approach for promoting improved maternal, infant, and young child nutrition (MIYCN) and hygiene behaviors in Keonjhar District, Odisha State, India. This pilot found the approach to be highly promising, and, in 2016, a group of partners led by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) began a randomized control trial (RCT) to assess the impact and cost-effectiveness of this intervention on maternal and child nutritional status (Kadiyala et al. 2014).

The LSHTM-led RCT, formally called “Upscaling Participatory Action and Videos for Agriculture and Nutrition” (UPAVAN), is exploring the effect of community video on nutrition outcomes. LSHTM is implementing the RCT with partners DG, the Voluntary Association for Rural Reconstruction and Appropriate Technology (VARRAT), JSI Research and Training Institute (JSI), SPRING, and Ekjut, with funding provided by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the UK Department of International Development. This report describes the results of formative research conducted in September and October 2016 in Keonjhar District, Odisha State, India, during the first year of UPAVAN.

1.2 Maternal and Child Health in Keonjhar District, Odisha, India

Demographic Summary of Keonjhar

Odisha (also known as Orissa) lies on the eastern coast of India. Keonjhar (also known as Kendujhar) district is located in northern Odisha, and is one of the least developed districts in India, ranked 507th of 599 districts on the District Development Index (POSHAN 2016). Keonjhar district has a population of 1,801,733 and a population density of 217 inhabitants per square kilometer. Keonjhar’s population is growing, with a growth rate of 15 percent between 2001 and 2011 (Census of India 2011).

The vast majority of Keonjhar residents live in rural areas (86 percent). Nearly half of households in Keonjhar (47 percent) live below the poverty line, and less than one third of households live in a permanent house (30 percent). Households in Keonjhar spend around 52 percent of their overall expenditures on food (POSHAN 2016). There is a marked gender disparity in literacy rates –86.8 percent of males are literate compared to only 66.3 percent of women (International Institute for Population Sciences 2016-2016). Hinduism is the predominant religion, with 98 percent of the district identifying as Hindu (Tripathi and Mohanty 2010).

Scheduled Tribes (ST) constitute 45 percent of the total district population, while Scheduled Castes (SC) constitute 12 percent (Directorate of Census Operations, Odisha 2011). ST and SC are more vulnerable than other non-ST/SC groups in northern Odisha. ST populations have much higher rates of poverty, with 73 percent of the tribal population in Northern Odisha living below the poverty line (Mehta 2011), and tribal populations are more vulnerable to food and nutrition insecurity compared to non-tribal rural populations (Das and Bose 2015).

While the majority (54 percent) of households are involved in agriculture to some extent (POSHAN 2016), research by Alan and Martin Rew in 2003 found that most households pursue diverse livelihood strategies, including farming, migrating for heavy manual labor jobs, mining, and trade (Rew and Rew 2003). They note that cultural identities like kinship, tribe, caste, and rank, as well as gender roles, play a part in determining acceptable livelihood activities for individuals and families (Rew and Rew 2003).

Nutrition Situation in Keonjhar

Undernutrition among women and children is very high in Keonjhar. Almost half (44.6 percent) of children under 5 years of age are stunted, 19.0 percent are wasted, and 44.3 percent are underweight (International Institute for Population Sciences 2016-2016). In addition, 32.7 percent of children 6–59 months are anemic (International Institute for Population Sciences 2016-2016). Women are also malnourished; 39 percent of women in Keonjhar have chronic energy deficiency (POSHAN 2016), and 40.5 percent of women aged 15–49 are anemic (International Institute for Population Sciences 2016-2016). Rates of overweight and obesity are relatively low, especially in rural Keonjhar, where only 10.6 percent of women and 13.8 percent of men are overweight or obese (International Institute for Population Sciences 2016-2016).

Infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices show much room for improvement. Rates of early initiation of breastfeeding are only 56.8 percent (International Institute for Population Sciences 2016-2016), and rates of exclusive breastfeeding are very low (34 percent) (POSHAN 2016). Only 9.2 percent of children aged 6–23 months receive an adequate diet (IIPS 2016).1 District-level data is unavailable for rates of child dietary diversity and complementary feeding in Keonjhar, but in Odisha state only 26 percent of children achieve minimum dietary diversity and only 55 percent of children 6–8 months old receive complementary feeding (POSHAN 2016). In rural Odisha, only 14.7 percent of children aged 6–35 months had consumed foods rich in iron and only 59.9 percent of children aged 6–35 months had consumed foods rich in Vitamin A in the last 24 hours at the time of the 2005–2006 National Family Health Survey (International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International 2008).

Health Situation in Keonjhar

Keonjhar residents have high levels of access to community health services, but the quality and utilization of health services is low. Ninety-eight percent of households have access to an Anganwadi worker (community health worker), and 98 percent of women have access to antenatal care. However, only 28 percent of households have access to a Sub-Health Centre (POSHAN 2016). Almost half (45.7 percent) of mothers have an antenatal check-up in the first trimester, 39.6 percent have at least four antenatal care visits, and 72.5 percent deliver with the assistance of a skilled health professional (International Institute for Population Sciences 2016-2016). Nineteen percent of children are born with low birth weights, the infant mortality rate is 53 per 1,000 live births, and the under-five mortality rate is 69 per 1,000 live births (Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India 2013). In addition, only 62 percent of children 6–35 months of age receive Vitamin A supplementation (Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India 2013). At the time of the 2015–2016 National Family Health Survey, 21.15 percent of children under 5 had had diarrhea in the last 2 weeks, and only half (56.2 percent) of those children had received oral rehydration salts (ORS) (International Institute for Population Sciences 2016-2016).

WASH indicators also leave much room for improvement. The rate of open defecation in Keonjhar is very high (85 percent) (POSHAN 2016). Access to improved sanitation facilities is very low (20.5 percent in Keonjhar, but only 13.4 percent in rural Keonjhar) and 85.4 percent of households have an improved drinking water source (82.9 percent in rural Keonjhar) (International Institute for Population Sciences 2016-2016).

1.3 Purpose and Objectives of the Formative Research

The objective of the formative research was to gain a deeper understanding of current nutrition-sensitive agriculture and nutrition-specific MIYCN and hygiene practices, priorities, and preferences of primary and influencing groups or audiences, and other barriers and facilitators of key practices in the study area. This research built upon the findings of formative research SPRING conducted in Keonjhar in 2012, which examined “current social and cultural determinants, practices, and knowledge of MIYCN” and hygiene (SPRING 2016). Based on the of The UPAVAN formative research prioritized exploring current nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices, knowledge, and beliefs, as well as addressing gaps and remaining questions from the 2012 research around MIYCN and hygiene practices, knowledge, and beliefs.

The findings of the formative research informed three key outcomes:

- Recommendations for nutrition-specific MIYCN/hygiene and nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices to promote in community videos. Social and behavior change (SBC) interventions such as this are more effective if they promote a limited number of practices (Lamstein et al. 2014). SPRING and its partners used formative research findings to identify a limited number of priority crops and livestock to promote throughout the intervention, as well as appropriate nutrition-sensitive agriculture and nutrition-specific MIYCN practices.

- Recommendations of key crops and foods to feature in community videos and to promote for cultivation and sale or consumption, based on nutrient content and community members’ perceptions of availability, affordability, tastiness, and healthfulness.

- Revisions to an existing MIYCN/hygiene training package, and the creation of a nutrition-sensitive agriculture training for community-level video production teams and extension workers. These training packages were adapted to the findings of the formative research and prioritized practices, and aimed to provide sufficient technical background for UPAVAN teams to produce videos and effectively mediate community video disseminations throughout the intervention.

2. Methods

SPRING developed a research protocol, instruments, and data summary and analysis matrices, which were then refined through discussion with UPAVAN partners. Focus group discussions included open-ended questions, a participatory food ranking using pile sorts, and an exercise to fill out daily activity charts for participants themselves and for their family members. The study team also developed an instrument for direct observation via transect walks through the selected villages. The study team submitted the protocol and instruments to review boards in India and the US, both of which granted approval.

2.1 Determining Priority Domains of Inquiry for Formative Research

Behavioral models, including the COM-B model (Michie, van Stralen and West 2011), the socio-ecological model (McLeroy, et al. 1988), and cognitive models, informed the design of the research protocol and instruments. These models tell us that to create an effective program UPAVAN will need to—

- promote practices in local terms (for example, what do respondents value in food?)

- link improved practices to short-term risks and benefits

- develop messages that get people’s attention and engage their emotions as well as their minds

- leverage existing social identities and gender roles (where possible) to enable, rather than constrain, participants to act on messages

- think about whether the enabling environment will support adoption of the practices UPAVAN promotes (USAID 2017).

UPAVAN partners used this behavioral lens to refine the project theory of change, which was informed by secondary data; conceptual models of malnutrition, including SPRING’s Agriculture to Nutrition Pathways (Herforth and Harris 2014) and the UNICEF framework for undernutrition (UNICEF 2013); and previous formative research and implementation work done by the partners in Keonjhar (SPRING 2016). The project’s theory of change at the time of the formative research design can be found in Annex 3.

Partners then used this refined theory of change to identify priority domains of inquiry to explore in the formative research, from which specific recommended practices developed. The priority domains of inquiry were not necessarily the only behavioral areas that would be promoted through UPAVAN, but were the areas in which the designers needed more information to tailor UPAVAN’s training and video content.

Domains of inquiry explored during the formative research:

- Household and community environment, markets, resources, and services

- Community priorities related to agriculture, livelihoods, and nutrition

- WASH practices, attitudes, and beliefs

- Gender roles, household relationships, and decision-making

- Gender roles, division of labor, and labor sharing

- Attitudes and beliefs related to commonly produced and/or purchased foods

- Farming practices, attitudes, and beliefs

- Seasonal challenges related to food security, income and expenditure, labor demands, and health issues

2.2 Methods Adapted for the Context and Domains of Inquiry

This research benefitted from the wide range of existing, widely used participatory and qualitative research methods—with published example data collection instruments—across nutrition, WASH, and food security. SPRING adapted and added to these existing tools, tailoring them to the priority domains of inquiry and the Keonjhar context. Table 1 indicates which methods or tools were most useful for each domain of inquiry, and identifies published resources where readers can access them.

Table 1: Methods and tools adapted Tools Adapted for the Formative Research

| Method/Tool | Domains of Inquiry | Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Transect walk |

| Adapted from Sphere for Assessment (Sphere Project 2014) |

| Seasonal calendar |

| Adapted from Formative Research: A guide to support the collection and analysis of qualitative data for integrated maternal and child nutrition program planning (CARE 2013) |

| Participatory food ranking |

| Adapted from Balancing nurturance, cost and time: complementary feeding in Accra, Ghana (Pelto 2011) |

| Participatory daily activity charts |

| Adapted from Formative Research: A guide to support the collection and analysis of qualitative data for integrated maternal and child nutrition program planning (CARE 2013) |

| Open ended focus group questions |

| Adapted from Formative Research: A guide to support the collection and analysis of qualitative data for integrated maternal and child nutrition program planning. (CARE 2013); and Focus on Families and Culture: A guide for conducting a participatory assessment on maternal and child nutrition (Grandmother Project (GMP) – Change through Culture 2015) |

2.3 Selection of Research Sites and Focus Group Participants

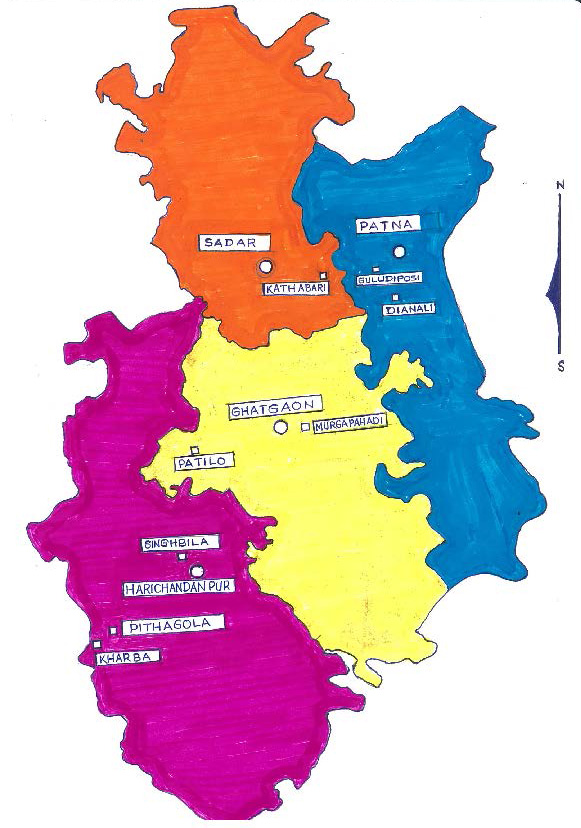

Sampling of communities and individual respondents was purposive and representative of the implementation area of UPAVAN. The sample included a geographically and demographically representative subset of villages. Sample size and segmentation of respondents was determined with UPAVAN partners, particularly DG, VARRAT, and Ekjut. Partners initially identified the following as characteristics with which to segment communities: primarily cultivating/primarily non-cultivating; close to block center/far from block center; tribal/non-tribal. Research mentioned above indicates that most households in Northern Odisha employ mixed livelihood strategies including farming, selling, and wage labor (Rew and Rew 2003). Partners told SPRING that the agro-ecological zones in the implementation area are homogenous, so the team did not segment by zone. Therefore, in the final study design, villages were segmented by the following characteristics: close to block center/far from block center and tribal/non-tribal. Table 2 shows which villages were selected, which instruments were used with which focus group, and how many participants were in each focus group. Figure 2 is a map, drawn by a VARRAT staff member, which shows the distribution of data collection sites (squares) as compared to block centers (circles) throughout the UPAVAN implementation area.

Figure 2. Data Collection Sites

Within each village, the study team held separate FGDs with pregnant women, mothers of children under two years of age, grandmothers of children under two years of age, and fathers of children under two years of age.

Table 2. Segmentation of Villages and Respondent Groups

| FGD--Pregnant women | FGD--Mothers of children 4–23 months | FGD--Fathers of children 4–23 months | FGD--Grandmothers of children 4–23 months | Transect Walks & Observations | ||

| Village A tribal Murgapahadi | Close to block center | A1-Food Ranking | A2-Daily Activity | A3- Food Ranking | A4-Daily Activity | Opportunistic |

| Village B tribal Dianali | B1-Daily Activity | B2-Food Ranking | B3-Daily Activity | B4-Food Ranking | Opportunistic | |

| Village C non-tribal Guludipasi | C1-Food Ranking | C2-Daily Activity | C3-Food Ranking | C4-Daily Activity | Opportunistic | |

| Village D non-tribal Singibila | D1-Daily Activity | D2-Food Ranking | D3-Daily Activity | D4-Food Ranking | Opportunistic | |

| Village E tribal Kathabari | Far from block center | E1-Food Ranking | E2-Daily Activity | E3-Food Ranking | E4-Daily Activity | Opportunistic |

| Village F tribal Kharaba | F1-Daily Activity | F2-Food Ranking | F3-Daily Activity | F4-Food Ranking | Opportunistic | |

| Village G non-tribal Patilo | G1-Food Ranking | G2-Daily Activity | G3-Food Ranking | G4-Daily Activity | Opportunistic | |

| Village H non-tribal Pithagola | H1-Daily Activity | H2-Food Ranking | H3-Daily Activity | H4-Food Ranking | Opportunistic | |

2.4 Enumerator Training

Each data collection team included a facilitator fluent in the local dialect of Odia, a note-taker who simultaneously interpreted some of the discussion for non-Odia speakers, and an observer who supported the facilitator with participatory exercises and noted overall group dynamics. In addition, a “floating observer” accompanied a different team each day, providing feedback to strengthen the quality and consistency of data collection across teams.

SPRING and Digital Green led a two-and-a-half-day training for data collection teams just prior to data collection. The agenda for the enumerator training is included as Annex 4. During this training, enumerators were trained in informed consent, translations and clarity of all the instruments were checked, teams were able to role play (e.g. facilitator, note taker, or observer), and teams practiced the participatory activities (food ranking and daily activity chart) with each other and then neighboring community members.

2.5 Data Collection

The study team conducted 32 FGDs in eight villages over two weeks. The team reserved a day mid-way through data collection to review the data collection process, begin data analysis, and make any needed adjustments to the instruments or process. When entering each village, teams began data collection by conducting a semi-structured observational transect walk through the village. These transect walks provided observational data to triangulate with FGD data.

As the FGDs took place in public spaces, and participants were busy preparing for upcoming festivals and the farming season, participant numbers varied over the course of a discussion—with a core of between four and eight who stayed throughout the discussion. Anytime a new person joined the group, enumerators verified that he or she was the appropriate demographic to participate in the group.

2.6 Data Entry and Analysis

Data collection teams processed the transect walk and FGD notes each evening, entering handwritten field notes into summary templates in Microsoft Word. Each night, all of the teams discussed in plenary how the day went, and whether there were any challenges or tweaks to the process that would be helpful for the next day.

Prior to data collection, SPRING developed data analysis matrices, which were then refined during analysis as themes emerged from the data. Starting in the field during and just after data collection, data was analyzed by all the partners according to overarching domains/themes, using grounded theory to identify emerging themes. Upon return from the field site, SPRING continued data analysis, and made recommendations for priority crops, foods, and improved practices based on the interpretation of findings.

All UPAVAN partners then collaborated to further refine SPRING’s recommendations and develop a list of video topics to promote specific improved MIYCN/hygiene behaviors and nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices, associated with a seasonal agriculture/livelihoods calendar. Partners used agreed upon criteria to help prioritize topics and specific behaviors, which are presented in the discussion section.

2.7 Research Limitations

The research team selected villages that were representative of the implementation area, segmented by important characteristics. Multiple methods were used to gather data from multiple types of respondents. This approach helped the team to triangulate data and develop an understanding of existing variation in knowledge, attitudes, roles, and practices. This research has limitations that are common to rapid, qualitative, participatory assessments. For example, researchers asked that respondents be randomly selected within villages to participate in FGDs, but often invited respondents were not able to come on the day of the study. In addition, if FGD groups were very small, community liaisons would often invite nearby mothers, fathers, or grandmothers to participate. This could have introduced bias in the data toward those who spend time closer to community centers, where discussions were held during the day.

3. Research Findings

The formative research aimed to better understand which small, doable, and impactful actions would fit with existing identities and priorities in communities and families. The findings suggest ways of promoting practices effectively based on the barriers and enabling factors identified by the research.

From the food ranking exercise, we learned which foods communities perceived positively, and which foods were unavailable or considered expensive or harmful—especially for women and children during the first 1,000 days. SPRING and project implementers used these findings to determine priority crops/livestock to promote for production, consumption and sale, and priority foods to promote for consumption. Nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices related to the priority crops/livestock include safely intensifying production, improving post-harvest processing and storage, or using income from sales to purchase desirable and healthy foods.

We also learned how respondents think about gender roles, decision-making about health care or money, and explored their ideals related to successful farming or good family relationships. For example, the ideal of a “good relationship” between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law and husband and wife includes “friendly” communication, task-sharing for food preparation and childcare, and joint decision-making about finances, agriculture, and festival observations (a year-round issue affecting spending and dietary decisions).

Encouraging findings related to increasing rest and reducing heavy work for pregnant women, and increasing women’s participation in farm and household decision-making. If these practices fit well within existing norms and family roles, they are more likely to be adopted, and thus more likely to contribute to nutrition. For example, respondents stated that husbands and grandmothers play important roles in caring for pregnant women, and that pregnant women should work less and refrain from heavy tasks.

The study findings have been organized by the domains of inquiry outlined in Section 2.1.

3.1 Household and Community Environment, Resources, and Access

The team observed variation between communities in terms of relative wealth, apparent water and sanitation resources, and market access. Houses in the study area are primarily made of mud, brick, or cement. Cement houses are less common. All communities include some houses with tile or straw roofs, and some communities include houses with cement, tin, or asbestos roofs. Most houses have verandas and are connected to electrical wires, save for the poorest villages. In some communities, televisions and satellites are very common, and in others they are rare or non-existent.

Most communities have at least one formal community meeting area, as well as informal meeting places around shops/markets, water pumps, or near main roads. Villagers in most communities had mobile phones. The study team observed more men carrying mobile phones than women, and noted that smartphones are less prevalent than standard mobile phones. Community members used phones primarily for calling and listening to music, although the team observed young people in one village sending text messages.

When the study team observed villagers washing their hands, most were not using soap. However, women and children were observed using soap to bathe. The study team observed villagers washing utensils or plates in most villages; in around half of these instances, villagers were using ash, and in the other half they were using water only. Every village had at least two public hand pumps and/or tube wells. At least one source is located near the center of each village, with an additional pump(s) or well(s) near the edges of the village.

The team observed hand pumps or tube wells being used for drinking water, bathing, handwashing, and washing household cookware. Nearby ponds were also used for washing and bathing. Water sources generally appeared clean and in good repair, although some were broken or not draining well and surrounded by puddles of water. In one village, the study team was told that water runs during limited hours. In general, villagers carry and store water using open metal pots; the study team observed women only carrying water. The study team observed a covered plastic container for water storage in only one village.

Latrine access and use varied. In some villages, there are few latrines and open defecation in nearby forests or fields is common, while in others, nearly every household has a latrine. Anganwadi centers occasionally have nearby latrines, and in some villages, there are latrines that have been built with government funds.

Animals are watered at nearby ponds or using pails of water drawn from water pumps. There is variation in animal penning. Some households tie animals near the veranda or front of the house, while others let them roam and graze freely in the village and surrounding area. Goats, sheep, and chickens are generally kept closer to the house, and cows often roam farther. Some households have cattle sheds or pens for cows at the front or side of the house. Chickens often roam freely. In half of the villages, children were observed near animals and animal feces. In most villages, animal feces are prevalent in the road and common areas, although they are often thrown away from the house or into common dumping ground. Animal feces tend to accumulate near cowsheds. Few study teams observed villagers cleaning animal feces, but those who did saw women using brooms, shovels, or hoes to move the feces.

Some villagers’ fields were immediately behind or beside their houses, and some villagers need to travel to fields. In general, villagers did not have difficulty accessing their fields. The majority of households (approximately 60–80 percent) have kitchen gardens with an area around 50–100 square feet. However, in one remote tribal village, kitchen gardens were uncommon. Kitchen gardens usually contain a variety of vegetables and spices. The most common kitchen garden crops include papaya, pumpkin, ladies’ finger (okra), brinjal (eggplant), greens (amaranth, spinach), ridge gourd, maize, a variety of grams (green, black, horse), chili, and turmeric. Drumstick (moringa), taro, cowpea, and beans were also observed.

Most villages do not have their own market, but many have small roadside stalls and shops and have good access to markets nearby. In most of these shops, soap is available, although prices vary widely, from 5–30 INR per bar. Farming inputs are only available at nearby markets. Small stands and shops often sell sweets or packaged snack foods, and occasionally sell fried foods, rice, daal (lentils), eggs, spices, or fruits, but vegetables are often not available in nearby shops. The team noted that those purchasing goods from these stands were mostly men.

3.2 Household Relationships

Many respondents, across most villages, shared a common vision of good relationships between daughters-in-law and mothers-in-law, and between husbands and wives. (See Text Box 1 for a selection of representative quotes expressing household relationships.) The main elements of good relationships are “talking friendly” together, sharing work, and reaching decisions together. Groups specifically mentioned discussing and deciding together on children’s education, finances, agriculture, and observing festivals. For mothers and daughters-in-law, eating together and going places together also indicate good relationships, as well as mothers-in-law helping more with children or cooking when their daughters-in-law are ill. Husbands helping their wives with childcare came up as a sign of a good relationship, as did wives serving food on time to their husbands. Respondents pointed out that family dynamics also depend on the personality of the family, saying: “There are families who love to quarrel.” In families where relationships are good, even when there is a problem, family members sit down and discuss the issue, “they don’t fight.”

Wives/daughters-in-law are not considered equal to their mothers-in-law even in “good relationships.” Daughters-in-law are expected to ask mothers-in-law for advice and permission to go places, and should anticipate and meet husbands’ needs, especially for food. All types of respondents mentioned financial hardships, dealing with extended family, husbands not helping with or shouting at/hitting children, and husbands (and in a couple of villages, mothers-in-law) drinking too much alcohol as family stressors.

Pregnant women and mothers

“We measure the relationship by how they talk together. If the pregnant daughter-in-law doesn’t eat, the mother-in-law insists that they eat and take rest. They make decisions, observe festivals, and go to market together, and the mother-in-law takes care of the children if she has time.”

“If the husband consults the wife on decisions that are important to the family, it is a good relationship.”

Grandmothers

“If the mother-in-law guides her daughter-in-law well, if there is coordination in their work, if they are sharing their work, if the mother-in-law loves her daughter-in-law as her daughter and the daughter-in-law loves her mother-in-law like her mother, we can say there is a good relationship.”

“If the daughter-in-law is serving food to the son, and the son is bringing something from the market (small gifts) for the daughter-in-law, that is a good relationship.“

Fathers

“[It is a good relationship if they are] cooperating with each other while cooking. For example, if the husband is handling the child while his wife cooks. If she gives us food in time, and if we give them some leisure time to spend.”

“You know if it is a good relationship by how they are talking and working. Example – they make decisions with the family about where to send the child to school, what to harvest, and how to observe festivals (for both mothers-in-law/daughters-in-law, and husbands/wives).”

3.3 Beliefs and Practices Related to Pregnant and Lactating Women’s Nutrition

Most respondents said that mothers-in-law and husbands are primarily responsible for caring for pregnant women. If there are unmarried sisters-in-law still living at home, they also help to take care of them. A few women said, “Our husbands care more for us,” but it was unclear if they meant that their husbands are more affectionate or if they do more to help care for them, or both. Mothers- and or sisters-in-law do more of the day-to-day care; for example, helping to care for other children so the pregnant woman can rest. Fathers make sure women are taking their supplements or medicine, and they accompany them to the clinic for appointments.

Women’s Diet during Pregnancy and Lactation

There is a recognized connection between a pregnant woman eating well and having a healthy child. Most respondents said that food is important to keep a woman strong throughout pregnancy, to help the child “grow healthy in the mother’s womb,” and to help with delivery; but a vocal minority across villages still believes that a pregnant woman eating too much may cause a difficult delivery.

Pregnant woman: “After birth the child will be good if she has eaten well during the pregnancy.”

Pregnant woman: “If the mother eats a lot the child will be good. If she eats too much the child will be big and it won’t get out during the delivery (bata mili bani).”

Mother: “If she doesn’t eat enough, the child will be weak, the mom will be weak too, and won’t deliver at the right time. They child may also die. If she eats enough, the child and mom will be good, the delivery will be good, she will not have pain during delivery, and the child will be safe and sound.”

Father: “Eat more, because she is eating for both herself and her child. Protein is very important at this time.”

Grandmother: “Now doctors are telling them to eat everything, but we don’t agree with doctor. We have delivered 4-–5 children with these rules. She should eat normally as before. During this, she should reduce in her food. Otherwise it will be a Caesarean baby.”

Mothers-in-law have a lot of influence on what pregnant women eat. When discussing food taboos during pregnancy, respondents consistently said, “She can eat everything.” Yet, upon probing, they listed foods that were harmful for either the mother or the baby. There was little consistency across villages about specific food taboos, except for common agreement that pregnant women should not consume “cold foods” (fruits and curd), big mushroom, pumpkin, liquor, and tobacco. Foods that were often mentioned as good included dal, greens, milk, vegetables, eggs, meat, and fruits (although many specific fruits were mentioned with varying frequency as restricted: jackfruit, banana, papaya, mango). Several groups mentioned the importance of protein and vitamins, but there was no consensus on which foods provided these nutrients.

Mother: “Our mother -in -law restricts us in some foods. If our mother -in- law restricts us we sneak the food.”

Grandmother: “Our grandmothers wouldn’t allow us to eat ridge gourd, big mushroom, pumpkin, jack fruit, but nowadays, we allow our daughters-in-law to eat all of these things except big mushroom.”

Mother: “How long can we eat like that? So sometimes we take daal from the other food and hide and eat it.”

Mother: “When the mother is pregnant they eat everything but during lactation they have a lot of restrictions. They eat twice daily only rice and salt and garlic, for like 2–-3 months.”

The mother-in-law is responsible for telling pregnant and lactating women what they should eat. In some villages, there are strict restrictions on women’s diet during the first two months after birth. Daughters-in-law in a couple of villages, after probing, recounted sneaking dal or other foods that AWWs recommend if their mothers-in-law forbade it. Most respondents still made a connection between pregnant and lactating women eating enough food to keep themselves and their children healthy. In most villages, respondents agreed that a lactating woman should eat more. One or two villages had extreme dietary restrictions for the first couple of months after delivery: Two to three months after delivery the mothers can eat dal and other things, but before that just rice, garlic, and salt.

There is a perceived connection between breastfeeding women eating enough food and producing enough milk. The team could not agree as to whether they should leverage exploit this perceived connection in messages about improved maternal diets, as it could prove a double-edged sword. While emphasizing the connection could motivate a family to support women eating more, it could also undermine confidence in producing enough milk, leading to the early introduction of other liquids/foods.

Women’s Workload during Pregnancy

There was consensus among respondents that pregnant women should work less and not do heavy tasks, but there may be variation in what is considered a heavy task. One specific concern was that heavy tasks put pressure on the baby in the womb. Heavy tasks mentioned included carrying water (many mentions), carrying firewood, sweeping the house, dehusking paddy manually, and going to the field.

Accredited social health activists (ASHAs) and doctors advise pregnant women to rest more and avoid heavy work, but respondents said that this does not mean that pregnant women should “sit idle” or “sleep all day.” In a couple of villages, men and grandmothers said pregnant women should work less, but the mothers said they were working the same amount.

Mother: We work the same amount. Even if we would want someone to help, who would do that? If we don’t do anything and sit idle for any period of time, they will say you are sitting idle at home doing nothing.

3.4 Infant and Young Child Feeding Beliefs and Practices

Childcare Support and Active Feeding

Fathers and grandfathers were unwilling to help feed children, as they felt it took too much time and was messy. Respondents felt that grandmothers were best suited to the task because they have the time and expertise. They mentioned that a grandmother will take time to sing and coax a child to eat, even using little games. Respondents also said that mothers were good at coaxing children to eat. There was no mention of forced feeding techniques.

Timing and Content of First Foods

Grandmother: “They breastfeed as long as the mother is able to give good milk, but after that they start complementary feeding.”

Usually the mother-in-law is tasked with deciding when to begin complementary feeding (sometimes in consultation with the mother or father). Some said that AWWs also influenced this decision. There seemed to be instances of both late and early introduction of complementary foods and there was no consensus on the appropriate age to start, with responses ranging from 3–4 months to 1 year. No difference was reported between the introduction times for boys and girls.

Mothers and mothers-in-law usually feed children after the first food ceremony. Sometimes sisters-in-law or husbands help. Usually the mother is the one who prepares the children’s food.

Animal Source Foods

Respondents had mixed feelings about the timeliness and appropriateness of giving young children animal source foods. There was no consensus within villages or among types of respondents. Many were concerned about a child of only nine months not of age having teeth to be able to eat meats or fish, and about not being able to digest meat or fish (of particular concern because of the bones). During the discussion, some suggested methods of preparing animal source foods, and discussed types of animal source foods that would be more appropriate for younger children. They proactively offered ideas for mashing or pressing fish, meat, and eggs to give to the child.

Pregnant woman: “The child should eat everything because this is when the child learns to eat and if they don’t try these things they might not have a taste for it. She should eat everything but in small quantities. If they eat more they might have a digestive problem.”

Mother: “The child needs protein at this time, and these foods can give protein to the child. The child can digest these foods. Some smash liver and give it to children, but some do not because the child doesn’t like it.”

Father: “Chicken liver is important for the child at 9 months.”

Awareness of Stunting

Using a visual aid of a stunted and a healthy child, the study team sought to understand respondents’ awareness of stunting as a nutrition issue. Respondents gave many explanations for why a young child would be shorter including: lack of food for the mother and baby, lack of immunizations or care, the stature of other family members, illness or disability, or insufficient milk or breastfeeding practices. Some villages mentioned that the mother and/or baby may lack vitamins, iron tablets, and IFA. One group mentioned that the short child may not wear slippers and so may have worms. Some respondents noted that money is needed for “good care” for the child to grow well.

3.5 WASH Practices and Beliefs

Wash Water Uses

Wash water is either not used (thrown away), used to water kitchen gardens/nearby plants/trees, or fed to cows (and sometimes goats). In most villages, it is reused for gardens or cattle.

Animal Feces Collection

Cow dung and all other animal feces are perceived differently and used differently. Cow dung is collected in all villages. Many villagers use cow dung to wash their floors and houses, some use it for fuel, many use it for pesticides or fertilizer. Some villages compost cow and other animal feces, and this may include children’s feces (one mention). Some villages throw the cow dung into a collective place (dump yard). We did not see, nor did people mention, pits for composting.

Separating Children from Animal Feces

Respondents understood the importance of keeping children away from animal dung. They cited skin infections, germs, and the possibility of children eating the feces, which might contain bugs. A few villagers said that children may touch the feces and put their hands in their mouth before washing them.

Respondents also said it was important to keep children away from animals generally, and therefore they tied animals far from the house. In one village, respondents mentioned keeping chickens away from children because there are bugs on the chickens. On the transect walks, the team observed animal feces all over roads and compounds. They did not see many compost pits or dump yards, nor did they see many animals tied. Some cows, goats, and sheep were tied, while chickens and dogs roamed freely.

Strategies mentioned for keeping children away from feces included placing cow sheds far from the house, making sure children wear slippers, watching children when they play outside, and washing their hands with soap and water if they touch feces. Those who washed their floors with cow dung said it was important to keep children outside of the house until the floor was dry.

Father: “Children’s feces are not as harmful because they are younger, there is not infection. Child is innocent, feces are innocent.”

Pregnant woman: “There is a difference in feces of elders and children. The child is only getting the milk and so their feces is cleaner. But feces is feces and flies sit on them and contaminate things. Some people do go for open defecation but most have toilets now.”

Beliefs and Practices Surrounding Children’s Feces

Many respondents believed that small children’s feces were not as harmful as older children’s and adults, or that they are not at all harmful. Reasons given included children not eating as much, not eating spicy foods, not eating pesticide contaminated foods, only drinking breastmilk, and the “innocence” of children.

Most people collect children’s feces or clean their bottoms and throw their feces near the house. In a couple villages, respondents said they throw the feces into streams or ponds. They wash the child’s clothes and the spot where the feces were, sometimes with straw, sometimes with soap or detergent. A few people mentioned helping children defecate in the toilet or throwing the feces in the toilet.

3.6 Division of Labor and Labor Sharing

As mentioned previously, working together and deciding who will do which tasks are considered signs of good family relationships. The team asked about whether families could make decisions together about work, and could share tasks among extended family members, especially to allow pregnant women and women who are exclusively breastfeeding more rest and time for care. Respondents mentioned two main types of barriers to these practices.

The first type of barrier is logistical or practical: Not all couples live with extended families who can share tasks, and there is a general shortage of farm labor in the area because of people migrating out of the area to earn, or going out for daily wage labor. Another barrier is that time for discussions and planning may be short, as family members are not together over long parts of the day. Respondents suggested that discussion about work planning and responsibility sharing could take place during the one meal a day that families spend together, or over tea.

The second type of barrier is related to gender roles and family stress. Community members noted that women have more limited experience outside the home, so men may be better informed to make decisions. There is widespread lack of awareness that women do so many tasks. The Daily Chart activity in the focus group discussions often prompted men and older women, and even the women themselves, to realize how busy mothers are, from before dawn until night. All of the groups who did the Daily Chart activity noted that late afternoons are a time when fathers and grandmothers are more likely to be home and not as busy, so they can help women with child care or other tasks at that time.

Father: “Our wives are doing small-small work in the house, but at the end of the day we see it is a lot of work.”

Multiple fathers’ groups: “We see that women work more than men because they do both household work and field work.”

In tribal areas specifically, there may be a more strict division of labor where women of reproductive age stay at home and men and older women do outside work like collecting forest produce, selling, field work, and marketing. This situation may make it harder for extended family members to share heavy household tasks or things like childcare with pregnant women and mothers in tribal areas, and thus harder for women in tribal areas to get more rest.

Other sources of family stress, which make joint decisions and work sharing more difficult, include alcoholism, money troubles, and conflict with extended family members. There was variation among respondents, but some talked about tension between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law.

Grandmother: “I do all the work in my house. My son earns income, and my daughter-in-law has time for resting, doing her hair, and gossiping.”

Regardless of specific practices being promoted, UPAVAN videos should model good decision-making and positive communication styles. Additional opportunities to help farming families build communication, planning, and joint decision-making skills should also be explored.

3.7 Attitudes and Beliefs Related to Specific Foods

The research explored the perceptions of respondents relating to dozens of common foods, through participatory food ranking exercises. The ranking was followed by more in-depth discussion of the results, including which of the most preferred foods are grown at home for consumption or sale, and which are usually purchased at the market or from neighbors. We combined local perceptions of the availability, affordability, tastiness, and healthfulness of these foods with nutrient content data of local varieties. The detailed findings can be found in Annex 5.

The team used these findings to develop a list of priority crops to promote for production through nutrition sensitive agriculture videos, and a list of priority foods to be promoted for women and children during the first 1,000 days through nutrition-specific MIYCN and hygiene videos. These recommendations are included as Annex 1.

3.8 Farming Practices and Beliefs

Respondents consider knowledge and access to improved technology to be important for farmers to succeed. They cited the following ttechnologies and improved practices (stemming from knowledge): row planting, hand cultivating using a cultivator, sustainable rice intensification, making and applying vermi-compost, and using tractors. The most successful farmers have year-round harvesting and diverse production, meaning they grow rice, vegetables, and legumes.

Mother: “”They can be successful with small land and [even if they are] poor if they apply manure, pesticide, and work sincerely, they will be good farmers.”

Mother: “If they take care of the field like a small child, they’ll be successful. The child grows from small to big, so they should take care of the plants to grow from small to big. ‘Choto pilabhali dekhiba (care for like a small child).’”

While respondents stressed the importance of access to inputs, land, and water for success, most said that with hard work, even small landholding or landless people can be successful. Livestock rearing mostly came up as a strategy for landless farmers, but some respondents did not agree, saying that when it comes to raising livestock, farmers need herds of animals to be profitable (e.g. 10-12 goats), not one or two.

Grandmother: “They also need good water, best pesticides, and perfect timing for cultivating or harvesting.”

Father: “Farmer doesn’t mean cultivation of paddy. We have some good farmers who cultivate poultry. For small and poor farmers, those who can do inter-cropping and multi-cropping, those who can do brinjal and potato along with paddy can be successful.”

Respondents said that vegetable gardening was challenging, because it required a regular supply of water and was therefore risky to grow for those without irrigation or close proximity to a stream. In addition, livestock could damage gardens that lacked adequate fencing. Only in one village did respondents mention having access to subsidized seeds and fertilizer. Key informants at VARRAT told the research team that there is a general shortage of farm labor because of young people leaving and men migrating for wage labor. Even if a farmer is financially able to hire workers, s/he may not be able to find them.

3.9 Practices and Challenges Related to Food Security

Rainy season is especially hard because there is less food available, no work to earn wages, and more illnesses, which cost money to treat and add to women’s care and labor burdens. Vegetables are scarce from March to May. Respondents specifically noted drumstick as a food they eat when food is scarce because it is easy and quick to grow, is available year around, and does not need a lot of water.

Father: “During this scarcity period we eat less green vegetables and more root vegetables like onions, and potato.

Coping strategies mentioned by most respondents included eating less, eating less expensive food, borrowing rice, and borrowing money. In one village, respondents mentioned selling forest produce and finding work for daily wages. All types of respondents said that when food is scarce, children eat first, followed by other family members, who share the food equally.

4. Initial Recommendations for Priority Practices

At the analysis workshops with DG and VARRAT during and just after data collection, we first defined what we meant by a “behavior” or “practice” (we use the terms interchangeably). We used the following statement: "Action is what counts!--a behavior/practice is an action that is done at a specific time and place by a person or group. Practices are measurable, but some practices are private or not directly observable, so can only be measured by proxies or self-report."

The following are the criteria the team agreed to use to prioritize potential practices. Much of this work to prioritize practices was done on the second data analysis day in the field, and on a half-day call on November 7, 2016 with the data collection team. The language is aimed more for nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices, but the characteristics hold true for nutrition-specific practices as well.

Agreed criteria to prioritize practices:

- Problem fit: adoption of the practice(s) contributes clearly to one or more intermediate outcome in the UPAVAN TOC

- Stakeholder fit: the practice(s) are feasible for community members to adopt, and adoption solves a problem that community members care about

- Activity fit: UPAVAN has the time, competencies, and resources needed to promote the practice, and no structural change outside the scope of UPAVAN is needed to enable adoption of the practice.

The team considered that practices which are more likely to be adopted and maintained over time—

- are done once or infrequently

- require little or no skill

- show immediate positive results

- are inexpensive to adopt

- require little time

- result in little or no risk

- fit existing social norms

- can be done with existing resources and technology

- require one person to do the job

- can be done in a single step

The team also recognized that it is important not to change too much at one time, as this could overwhelm project staff and resources, and project participants. UPAVAN’s design allows for promotion of a changing package of practices over the life of the project, to have a cumulative effect. In selecting priority practices, the team used the following guiding principle: All things being equal, UPAVAN will first do those things that require the least time and resources for community members to adopt, and yet will lead to impact.

Priority Practice Recommendations

The following are the priority practices which SPRING initially recommends, coming from the prioritization process described above. These recommendations will be refined as partners create an implementation plan—linked to agricultural seasons—for developing and disseminating the videos. Please note that these are practices, not messages to promote practices. The messages are created as specific storylines and a package of practices (POP) document is developed for each video. For detailed recommendations including barriers and enablers for each practice, see Annex 2.

- When making plans for earning and expenditures, husbands and wives discuss and make decisions together, including in-laws as appropriate. Before changing plans and making decisions, they discuss again with each other and their family members.

- Family members regularly discuss the allocation of labor and money for WASH, food purchase and preparation, care, and feeding.

- Pregnant women and those who gave birth within the previous six months (during exclusive breastfeeding) should not:

- fetch water, carrying water on head

- clean animal sheds or do other heavy cleaning

- bend down to transplant seedling or weed by hand

- apply pesticides or fertilizer/manure to crops

- harvest and carry harvest

- do heavy crop processing, including manual rice dehusking

- collect and carry heavy forest produce (e.g. wood)

- carry soil or manure

- engage in house construction related activities

- Other family members should do these tasks while women are pregnant and for six months after birth.

- Each day, when they eat together at lunch or dinner, the family (the couple and other adults in the household if they live in the same compound) discuss workload sharing. (For some families, it may work better to discuss these matters in the evening while having snacks during leisure time.)

- Family members should regularly discuss—

- what we did today

- what needs to be done in next 1–2 days

- where everyone is ok, whether anyone is sick, and if so, whether anything needs to be done

- whether any family member needs help with any work. Each member (especially husbands, mothers-in-law, sisters-in-law, fathers-in law) should offer to help with strenuous or time-consuming work (especially for pregnant and lactating women).

NOTE: DG already includes this in one video done with SPRING about workload during pregnancy, in which a husband sees his pregnant wife working in field, asks her to rest, and does the work instead.

- Pregnant women and those who gave birth within the previous six months (during exclusive breastfeeding) take frequent breaks during daily work. (e.g. not standing or walking for too long).

- Pregnant women and those who gave birth within the previous six months (during exclusive breastfeeding) rest (lying down) for two hours after lunch and should rest for at least eight hours at night. Resting doesn’t necessarily mean sleeping, but quietly taking rest. For example, it’s possible for a mother to breastfeed while resting.

NOTE: In further discussion with partners, this practice was modified to resting or lying down for 1 hour after lunch. VARRAT and DG noted that the government is promoting two hours of rest during the day and eight hours of rest at night for pregnant and lactating women.

- Caregivers tie animals away from spaces where infants/small children play or people spend time in the compound, and away from walkways into the house

- Children wear slippers outside as soon as they start walking.

- Small children always play on mats and have someone watching them for stimulation and safety.

- Caregivers ensure there is a clean, enclosed space for the child to play in, which could be a gated room, veranda, or fenced in area.

NOTE: Partners agreed to delay promoting practice 11 and 12 until further formative research is complete; e.g. trials of improved practices can be done to identify feasible practices to keep children away from human and animal feces.

- Household members collect animal feces daily from the compound and follow improved composting practices at the household level. The place of composting should be far from where children play.

- Household members dispose of children’s feces using the “cat” method (burying) or toilet disposal (if there is access) and promote adding ash especially during rainy season (to speed up decomposition).

NOTE: Upon consultation with WASH experts, we learned that this is not necessarily a best practice. Thus, we recommend focusing on handwashing with soap and water at critical times until there is more clear evidence about safe alternatives to latrines.

- Pregnant women eat one extra meal a day. If they experience indigestion, pregnant and lactating women can eat small meals throughout the day. (Include sample snacks like chhatua and suggested times for extra food).

- Breastfeeding women eat two extra meals and/or snacks a day.

- Every day, pregnant and lactating women should have green foods and orange foods. It is okay to substitute a food of a similar color if a food is not available or preferred.

- Every day, pregnant and lactating women should have at least one type of animal source food, either meat, eggs, or milk.

- Restrict intake of processed sugary, salty, and oily foods and snacks, alcohol, and tobacco.

- Plan and grow kitchen gardens to increase family access to orange and green fruits and vegetables. (Videos can promote specific fruits and vegetables based on priority foods/crops for a given season.)

- Other household members remind/encourage pregnant and lactating women to eat extra and diverse foods.

- Mothers-in-law or sisters-in-law help prepare additional healthy meals for pregnant and lactating women.

- Household members help ensure that there is sufficient and diverse food for pregnant and lactating women to eat (harvest, purchase, exchange, collect, etc.).

- Practice optimal complementary feeding:

- Introduce first foods at 6 months.

- Continue breastfeeding until the child is at least 2 years of age.

- Obtain eggs and chhatua from AWW center for children over 6 months to eat as complementary food.

- Prepare chhatua as a complementary food with varied nutrient-dense ingredients.

- Ensure complementary food is the right consistency.

- Feed the optimal amount at each setting and the optimal number of times a day for age and health status.

- Feed a diverse nutrient-dense diet.

- Feed animal source foods regularly, starting from 6–7 months of age, with age appropriate preparation (the official national guideline may have changed to 7 months).

- Recognize the difference between regular changes in stool (of no concern) and diarrhea (of concern).

- Practice active and responsive feeding.

- Do not feed processed sugary, salty, oily foods and snacks, especially biscuits, as a complementary food.

- Mothers-in-law, sisters-in-law, and fathers support and participate in care and feeding.

- Everyone washes their hands with soap or ash and water before preparing foods, feeding children or themselves and after using the toilet, cleaning the baby’s bottom, and coming from the field or handling livestock.

- Everyone prepares food with clean utensils, which will be washed with ash or soap.

- Food preparers and servers keep food covered after preparation and eat it within two hours at room temperature. Food preparers and servers dispose of food that has been sitting out longer than two hours.

- Point of use water treatment (boiling and household storage).

NOTE: In preliminary discussions of the formative research findings, partners decided not to focus much on this. Videos will mention using clean water for cooking, washing, and drinking.

- Retain nutrients and safety, and reduce crop loss, by—

- harvesting crops at the correct time

- sorting out bad or damaged grains, leaves, etc.

- drying properly, in a safe place for the correct length of time, and preventing contamination

- storing properly away from light, moisture, molds, insects, and rodents

- checking stored foods periodically, sorting and disposing of spoiled food

Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture Practices Related to Specific Priority Crops and Livestock

The team developed a list of priority crops to promote through nutrition-sensitive agriculture videos and a list of priority foods for women and children during the first 1,000 days through nutrition-specific MIYCN/hygiene videos. These lists are included as Annex 1. As POPs and storyboards are developed for priority crops/livestock, the UPAVAN team can identify which nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices are most relevant for a given crop/livestock.

Along with the initial recommended practices listed above, SPRING also developed guidance, with criteria for nutrition-sensitive agriculture videos as well as a list of questions to help the teams develop and/or refine new nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices, whether cross-cutting or related to a specific crop or livestock. The intention is for UPAVAN implementers to apply these criteria and questions when they are contemplating adding new nutrition-sensitive agriculture topics into the roster of videos.

Requirements and Considerations for Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture Videos

Requirements:

- Out of the total 5 (max) key messages, include at least 1–2 that are focused on nutrition-sensitive agriculture (NSA); i.e. something about increasing access to food, health, or care through agriculture

- Guiding questions (listed below) can help you to think through or consider how agriculture practices may affect nutrition

- Criteria for prioritizing selected nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices (listed below) can also help to prioritize the selected nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices.

- Any key messages which are not nutrition-sensitive agriculture should be agriculture-specific.

- Nutrition-sensitive agriculture videos should not include any nutrition-specific messages. When thinking through practices, if the practice increases resources for or access to food, health, or care, it is nutrition-sensitive agriculture; if it is a feeding, caring, or health-promoting practice, it is nutrition-specific. For example, within a nutrition-sensitive agriculture video, it is fine to say that a nutrition-specific practice such as handwashing improves the health of families, but nutrition-sensitive videos should not provide instructions on how to perform a nutrition-specific practice in detail, such as demonstrating the handwashing steps.

Guiding Questions for Consideration:

Category 1: Women’s Roles

- Who is primarily responsible for carrying out/using the targeted agriculture practice(s)?

- If women are involved, does the practice pose additional timedemands on them?

- If so, what might assist in reducing this time burden, especially for pregnant and lactating women?

- Do key influencers (e.g. husbands and mothers-in-law) understand and support the need to promote adequate time for breastfeeding, child care, rest, and self-care by women of reproductive age?

- If women are involved, does the practice pose a heavy laborburden on them?

- If so, what practice(s) or technologies might assist in reducing this heavy labor burden, especially for pregnant and lactating women?

- Do key influencers (e.g. husbands and mothers-in-law) understand and support the need to mitigate heavy labor expenditure for pregnant and lactating women?

- If women are involved, does the practice pose additional timedemands on them?

Category 2: Production of Diverse Nutrient Rich Foods

- Is the promoted product (e.g. vegetable/fruit/staple crop, livestock, poultry, fish, etc.) nutrient-rich?

- If so, is some portion of the total production being retained for household consumption?

- How frequently will the crop or food product be available for consumption?

- What can be done to increase the demand for nutritious foods?

- Is there a way to extend the time period available for consumption and/or sale of the product?

- Is there a way to maintain the nutrient quality of the product over a longer period of time (e.g. through storage, value addition, technologies such as solar refrigerators)?

- How are decisions made at the household level about what to grow and what to sell?

Category 3: Use of Income for Food, Health, and Care

- Are the agricultural products being grown/promoted contributing to household income?

- If so, is household income increased through the sale of the promoted product(s)?

- Is household income increased over a longer period (increased number of months with adequate cash to meet food, health, and care needs)?

- Is the household preparing for periods when there is less food?

- Is the household preparing for periods when there is less income?

- Does the household maintain a budget that includes cash needs for both livelihood and food, health and care needs?

- Is the household aware of and able to spend its income on more, diverse foods? On health care? On WASH services and products?

- How are decisions made at the household level about what to grow and what to sell?

- Are there supportive services that the household can access to improve its agricultural production? If so, does the household know about these services?

Category 4: Food and Environmental Safety—Do No Harm

- Do any of the agricultural practices being promoted involve use of chemicals(e.g. chemical fertilizers, herbicides, or pesticides) or non-chemical fertilizers, such as compost?

- If so, are pregnant or lactating women exposed to these? What risks might these pose?

- If so, what risks might these pose to household members?

- If so, what risks might these pose to sustainable production (e.g., soil health)?

- If so, what risks might these pose to water resources?

- If so, what risks might these pose to food quality and safety?

- What might be done to mitigate this (these) risks?

What conditions are necessary to improve or maintain food quality at harvest, in storage, and in households? How can these conditions be achieved?

Further Criteria for Prioritizing Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture Practices:

- Is this a nutrition-sensitive agriculture practice? – The practice falls under the above criteria.

- Potential impact on problem – This practice will contribute to nutrition-sensitive outcomes (e.g. availability and access to diverse nutritious food, income for investment in food, care, health/WASH, mitigating excessive demands on women’s time or energy).

- Feasibility– The practices are feasible for target groups to adopt and to maintain over time given the current context and resources.

- Appropriateness – Is this practice appropriate for the crop you would like to promote?

- Major barrier – Are there major cultural, physical, or financial barriers to overcome?

- Access/Market supply – Is there access to necessary resources (e.g. inputs, credit, training) to adopt and sustain behaviors?

5. Conclusion

This report reflects the findings and recommended practices, barriers, enablers, and priority foods and crops devised based on feedback from all UPAVAN partners. The next step for SPRING will be to update the MIYCN/Hygiene and hygiene training package, develop the nutrition-sensitive agriculture training package, and support the training of trainers and rollout of these trainings to community workers. These packages will include general technical background as well as some of the specific recommended practices, along with a discussion of barriers and enablers identified in this formative research. The next step for all UPAVAN partners will be to decide on the number and sequencing of videos and to then create the POPs and storyboards for those videos. This process is continuous and will take place throughout implementation.

To view the annex, please download the full report above.

Footnotes

1 An adequate diet is defined as: “breastfed children receiving 4 or more food groups and a minimum meal frequency, non-breastfed children fed with a minimum of 3 IYCF Practices (fed with other milk or milk products at least twice a day, a minimum meal frequency that is receiving solid or semi-solid food at least twice a day for breastfed infants 6–8 months and at least three times a day for breastfed children 9–23 months, and solid or semi-solid foods from at least four food groups not including the milk or milk products food group)” (IIPS 2016).

References

CARE. 2013. Formative Research: A guide to support the collection and analysis of qualitative data for integrated maternal and child nutrition program planning.

Census of India. 2011. Kendujhar. http://www.dataforall.org/dashboard/censusinfoindia_pca/ (accessed 03 14, 2017).

Das, Subal, and Kaushik Bose. 2015. "Adult tribal malnutrition in India: an anthropometric and socio-demographic review." Anthropological Review 78, no. 1 (2015): 47-65.

Directorate of Census Operations, Odisha. 2011. Census of India 2011 Odisha: District Census Handbook Kendujhar. Bhubaneshwar, India: Directorate of Census Operations, Odisha.

Grandmother Project (GMP) – Change through Culture. 2015. Focus on Families and Culture: A guide for conducting a participatory assessment on maternal and child nutrition.

Herforth, Anna, and Jody Harris. 2014. Understanding and Applying Primary Pathways and Principles. Brief #1. Improving Nutrition. Arlington, VA: USAID/Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project.

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. 2008. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), India, 2005-2006: Orissa. Mumbai: IIPS.