Using the Power of Participatory Storytelling to Improve Nutrition

Contents

INTRODUCTION

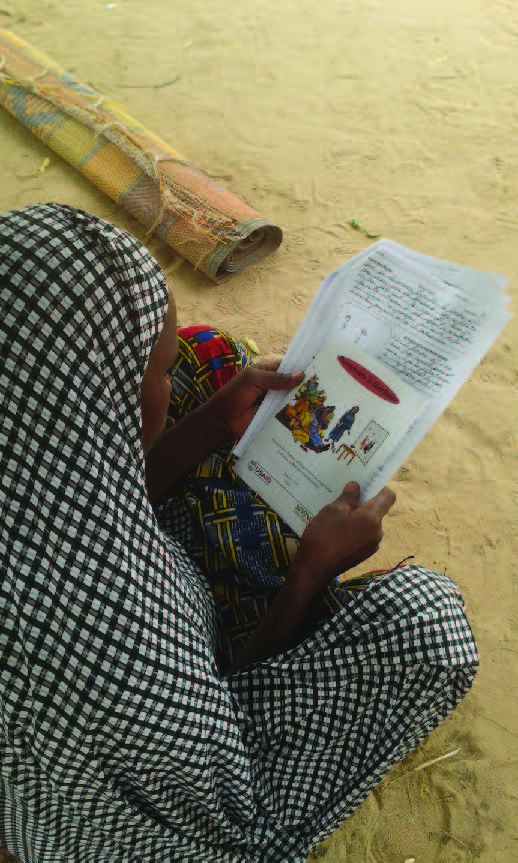

For thousands of years, traditional storytelling—the most basic approach to communication and knowledge transfer—has been used to help change or reinforce social norms and promote the adoption of individual and community-level behaviors. Thanks to modern media technologies, storytelling can now have an even broader impact on communities and individuals, motivating them to improve the nutrition and health of families, friends, and neighbors. Over the last five years, USAID’s multi-sectoral nutrition project, SPRING, has embraced the power of storytelling through various community media platforms and experimented with several innovative technology-enabled storytelling techniques to change nutrition-related behaviors and social norms.

Through storytelling, people pass on important knowledge by evoking imagery and triggering emotions, sentiments, and physical responses that make the narrative resonate with an audience. In 2012, SPRING began encouraging the participation of community members in the creation of stories to promote nutrition and hygiene through distinct community media channels. We have developed this document to help guide program managers and other decision-makers considering the use of various types of community media. In these pages, we describe relevant experiences, tools, evidence, and lessons learned. Reflections on earlier definitions and principles of community media are also presented for readers interested in further exploring the foundations and key concepts of this approach.

Evidence shows that sustained improvements in nutrition practices are often achieved through long-term, repeated exposure to behavior-centered communications programming, reinforced by other complementary activities. Successful strategies for SBCC interventions include employing multiple channels and media, as well as engaging key audiences and influencing groups (Lamstein et al. 2014). SBCC acknowledges that individual decisions, behaviors, and practices are influenced by a web of complex, contextual determinants that must be addressed to effectively encourage people to try, adopt, and maintain improved practices.

Since 2012, SPRING has invested in exploring and evaluating the role and effectiveness of storytelling in SBCC, with a focus on several specific community media tools. Community media allows us to share stories that are both interesting and compelling, while also conveying appropriate health and nutrition information. This approach leverages and maintains the integrity of local experiences and narratives, while using innovative dissemination channels to reach large numbers of individuals to excite, motivate, and empower communities to move toward improved nutrition and health.

This review presents in-depth case examples of how we have used this approach in multiple contexts. Through honest and pragmatic reflection on lessons learned through our country-level programs, we hope to further support the application, adaptation, and evaluation of community media in other programs and contexts, especially to improve nutrition and hygiene.

Health Education, SBCC, and the Rise of Community Media

Disseminating health and nutrition information and motivating people to adopt new behaviors, especially in communities where health literacy is low and infrastructure is poor, represent ongoing challenges for global health practitioners. Interpersonal (face-to-face) communication, although an effective SBCC technique, generally has limited reach given constraints on people’s time, distance, and resources. Mass media for health education is also limited in that it is a one-way communication channel, with information traditionally flowing from urban centers outward, only sometimes reaching remote populations. It follows that many long-established health communication techniques enable only a limited exchange of ideas and input from and within communities (Berrigan 1979). The increasing visibility of social justice movements from the 1960s onward, however, has brought with it a growing focus on grassroots and community media as instruments of social change, underscoring the need to more actively engage communities, provide an opportunity or space for the exchange of ideas, and stimulate enriching two-way communications (Howley 2010).

Community media’s popularity and evolution over recent years has been heightened with the rapid expansion and reduced costs of information and communication technologies (ICTs). The application of ICTs for health, nutrition, and agriculture has opened up vast new opportunities to exchange information and ideas and engage the most remote and marginalized populations. The increasing use of portable, digital-based community media tools for SBCC has the potential to expand reach, standardize health information, and provide platforms that encourage feedback, dialogue, and interaction around content delivery and modification (Strack 2015). The expanding reach and accessibility of digital tools is a phenomenon transforming our traditional options for SBCC programming in all corners of the globe, representing a huge opportunity for reaching individuals and families via community media.

From January 2015 to January 2016 alone, the largest expansion in access to online ICT was reported in Africa, with Internet use increasing by 14 percent and social media usage up by 25 percent (see Table 1). Though the first mobile phone adopters are primarily male, educated, young, wealthy, and urban, secondary adopters across the demographic spectrum, including more poor, elderly, and rural individuals, have been gaining access to the technology, thanks in part to the introduction of lower-priced models and the availability of airtime cards at lower price points (Aker and Mbiti 2010). The growing accessibility of new media technologies can democratize information, giving those most affected by health and nutrition problems greater access to information, and ideally, a greater voice in discussing and addressing these problems (Ali 2011).

Table 1. Digital Annual Growth (January 2015–January 2016).

| The Americas | Europe | Africa | Asia- Pacific | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet usage | +6% 38.9 million | +4% 25.9 million | +14% 47.2 million | +12% 199 million |

| Mobile connections | +1% 9.6 million | +1% 13.5 million | +9% 84.4 million | +4% 156.6 million |

| Social Media | +6% 28.6 million | +3% 11.2 million | +25% 25.3 million | +14% 145.8 million |

Defining Community Media

Community media has no single definition or specific approach. The advantage of community media is that it combines some of the major benefits, elements, and strategies associated with both mass media and interpersonal communication (IPC) techniques while tapping into storytelling traditions. Community media is tailored to the local community it serves, and community members are involved as active participants in the process. A review of the literature reveals a wide range of media-related tools currently used in health and nutrition programming that are considered community media approaches, including video, radio, television, photography, and web-based social media. More traditional, lowtech tools are also sometimes associated with community media, and include puppetry, drama, plays, song, dance, festivals, and storytelling as entertainment. However, no single, commonly accepted definition of community media predominates in the literature. A wide variety of other terms are used in relation to community media, such as “citizens’ media,” “alternative media,” “indigenous media,” “folk media,” “grassroots media,” “participatory media,” “amateur media,” and “radical media,” each with its own definition and principles.

We did, however, find two common characteristics that form a basis for our understanding community media: 1) access and level of participation and 2) local and culturally appropriate content.

Access and Level of Participation

Traditional mass media campaigns typically have little room for community-level participation (Morris 2003; Servaes and Patchanee 2005). In contrast, community media incorporates dialogue and interaction to function as a transformative process that occurs between individuals, communities, and institutions (Singhal 2001). Table 2 identifies the fundamental distinctions between typical mass media and community media.

Table 2. Communication Approaches in Communication for Development

| Mass Media | Community Media |

|---|---|

| Vertical (top-down) approach to programming | Horizontal programming |

| Message to persuade/outcome-focused | Process-oriented problem-solving and engagement |

| Focus on individual behavior | Socio-ecological approach |

| Unilateral structure | Dialogic, bidirectional process |

| Passive design: targets audiences | Active design: interactive with communities and stakeholders |

| View of culture as an obstacle to behavior change | Collaboration with culture to enable behavior change |

Berrigan’s (1979) theoretical studies on the importance of community media as a communication tool for development identified two critical concepts, which have informed many subsequent definitions of community media: access and participation (Howley 2010). Access refers to the availability of communication tools and resources for members of the local community to express themselves collectively or individually, including the ability to receive information regardless of remote geography, class, ethnicity, or gender (Fairbairn 2009; Berrigan 1979). The level of access to community media has a direct relationship with the level of community participation.

Participation can mean the involvement of the community throughout the design, production, and implementation processes (Berrigan, 1979). This concept of participation is also found in the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) definition of community media as “in the community, for the community, about the community and by the community” (UNESCO 2016). The World Bank acknowledges that communities, stakeholders, and donors all have very different notions of what participation looks like, why it is necessary, and for whom it is most important (Tufte and Mefalopulos 2009). This idea of a scale of participation is illustrated in Figure 1; it can be viewed as incremental steps from a token level of participation to full ownership of the process.

.st0{fill:#F37321;} .st1{fill:none;stroke:#000000;stroke-width:0.52;} .st2{font-family:'Arial-BoldMT';} .st3{font-size:10.049px;} .st4{fill:none;} .st5{font-size:11.9439px;} .st6{fill:none;stroke:#FEDFC7;stroke-width:1.04;} .st7{fill:#FEDFC7;} .st8{fill:none;stroke:#7F7F7E;stroke-width:0.25;} Allowed to join (others’ rules) Attend meetings Speak Up FIGURE 1: PARTICIPATION LADDER Listened to Influence decisions Make decisions Set own rules TOKEN PARTICIPATION ACTIVE PARTICIPATION DECISION MAKING OWNERSHIP AND CONTROL

There is some disagreement as to whether community activities that engage participation at the lower levels of the ladder should be seen as community media; different organizations may consider different levels of participation as constituting community media. However, even the lower levels of engagement, including the opportunity to join a group and attend meetings, are critical components of community media in that they provide a voice for local representation, particularly for groups of people who may traditionally have less access to media, or who do not see their own views and circumstances reflected in traditional media. Community media can also be used to facilitate and build capacity for fostering debate, often providing a platform for marginalized indigenous voices (Buckley 2011; Fairbairn 2009; FAO 2003).

Local and Culturally Appropriate Content

The rapid acceleration of globalization as well as communication technology has facilitated the exchange of ideas, knowledge, and culture between populations and across borders, often at instantaneous speed. In contrast, community media is often distinguished by its hyper-local content, commonly defined by the geographic location in which it was produced and for whom it was intended. Even so, community media locally produced in one corner of the globe can have a social, cultural, or economic impact in another. The success of this approach depends on two factors: First, the locally produced content must evoke trust in the target community. Second, community members must identify with the participants involved in the production. Both of these tasks may be accomplished if participants are real community members as opposed to fictional characters or actors. Role modeling is an important behavior change concept reflected in community media programs; when individuals see someone of similar means successfully trying something new, they feel like they too can adopt the new behavior. This concept is not as effective when the content is not contextualized and the viewer cannot identify with the person who is role modeling, especially when attempting to change behaviors strongly related to cultural and social norms, as many health and nutrition behaviors are.

The SPRING Definition

Community media is constantly evolving as it combines and uses emerging technologies and traditional communication platforms to better serve unique community needs. Community media’s ability to deepen community participation, access, social learning, and engagement is increasingly made possible through the use of ICTs. The focus on innovative approaches in communication for development does not call for abandoning traditional communication methods, but rather focuses attention on the growing acceptability of ICTs and their potential to enhance the reach and scalability of development programming. This fluidity, which makes community media a challenge to define, may be its greatest advantage as an effective SBCC approach.

Drawing from the characteristics and definitions of community media presented above, SPRING considers community media to be any form of technology- enabled media that, to varying degrees, is developed in the community, about the community, and with the community.

Principles for Effective Community Media

The range of community media tools and formats makes it an attractive health communication or SBCC approach that can be applied to interpersonal, community, and institutional settings. Based on our experience of implementing community media projects around the world, we have defined four principles that should be considered in the design of effective community media programs.

The Principles of Community Media

Community Engagement

Inherently, community media offers a wide spectrum of community engagement. This continuum of participation often includes a broad range of internal or external actors and intermediaries, depending on the requirements and desires of the program. Nevertheless, appropriate and successful programming requires that, whenever possible, community members have the opportunity to meaningfully engage throughout all phases of the design and implementation process. In this sense, community participation and ownership as a principle of community media not only guides the process, but in some cases can also be a long-term goal and intention of the activity. In the context of promoting health and nutrition, community participation helps ensure that the content is appropriate and the behavior or practice being promoted is feasible. It also helps promote trust in the information being shared, as well as community buy-in to the process or program.

Effective community media must ensure that the content and format of communication materials are acceptable and relevant to the target population, based on a clear understanding of, and adaptation to, the local context. This requires a careful balance between working within existing cultural and social systems, avoiding the reinforcement of harmful practices and relationships, and communicating the benefits of new behaviors and social norms. Our experience is that consumers of community media need to hear and see themselves in the audio and/or visual materials. They need to identify with the environment and characters—the families and individuals featured in the media—and believe that they can experience a similar change or impact in their lives.

Capacity Building

Community media approaches build individual, community, and institutional capacity through training and peer-to-peer support groups and networks. This capacity building can take one or more of these forms: 1) building the necessary technical and production skills of actual community members, who are then engaged in various elements of the community media activity; 2) engaging community members as players or actors in the production of community media, telling their own stories and/or allowing their voices to be heard; and 3) supporting communities to transform this dialogue into tangible, systemic changes. This principle of capacity building also helps build the sustainability of the work by transferring the capacity to develop community media programs from external technical assistants to community members themselves.

Sustainability

Community media can achieve sustainability in a number of ways. Careful and strategic planning can ensure that these efforts build lasting institutional partnerships and support so that communities can continue to access the resources necessary for self-directed community media. The other key principles for effective community media—community engagement, capacity building, and contextualization—also help ensure sustainability, so that efforts can continue beyond donor activity timelines. If communities can continue developing and disseminating media beyond the intervention, the impact of the work will continue to grow.

Types of Community Media Approaches

The body of literature describing or demonstrating the effectiveness of a large range of community media approaches is expanding rapidly. This section describes specific examples of technology-enabled community media that have proven successful in the field of SBCC as informed by many of the themes, theories, and principles outlined earlier.

Community Radio

Community radio is considered a powerful development tool through which to influence, educate, and mobilize a broad range of people. International agencies and the donor community have contributed to the establishment and expansion of community radio, and donor support has, in some cases, assisted with licenses, transmitters, and broadcasting equipment (FAO 2003). However, community radio stations function in a variety of ways, often joining networks to amplify their content, support each other in capacity building, and ensure institutional sustainability (BNNRC n.d.; Buckley 2011). Community radio has an extraordinary reach, with the ability to connect with millions of people at once. For example, the World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters, a global membership organization for community radio stations, has almost 4,000 members in 150 countries (AMARC 2017), and that number does not include the likely thousands more grassroots stations that function without representation.

The impact of community radio in promoting and sustaining behavior change and engaging a broad spectrum of community participation has been well documented. In Kenya, for example, Mtaani Radio, run by a team of community-based volunteers in the Kawangware slum of Nairobi, responded to the 2015 cholera outbreak affecting their community. By broadcasting public service announcements and responding to community queries, Mtaani Radio was able to inform and educate as many as 10,000 people on water, hygiene, and sanitation practices to help manage the outbreak (Njuguna 2016). In countries where most media are controlled by the state, community radio can provide an alternative information source. In South Sudan, for example, UNICEF’s Community Radio Listening Groups project works with a community radio network to air key messages promoting children’s rights as well as broader health messages. Initially, opportunities for community engagement were limited to participation in listening groups; however, participation increased over time to include systems for community feedback and content production (NHD 2009). A program highlighted in the Principles in Practice case examples details SPRING’s partnership with Development Media International in Burkina Faso, where we collaborated to engage seven local radio stations in adapting nutrition messages for different regions and languages, reflecting local context. These examples illustrate the importance of contextualizing community radio based on the realities on the ground, including complex sociocultural and political settings. They also highlight the importance of various types of partnerships and related opportunities for capacity building.

Many radio projects now also leverage new technological solutions that increase relevance and access to a broader population. In Fiji, femLINK’s mobile radio initiative FemTalk takes a suitcase radio to women living in remote rural and peri-urban communities who otherwise would not have access to this information. FemLINK Pacific has also embraced social media to diversify the accessibility of content through podcasts and YouTube, as well as Facebook and Twitter (femLINK Pacific 2014).

Community Video

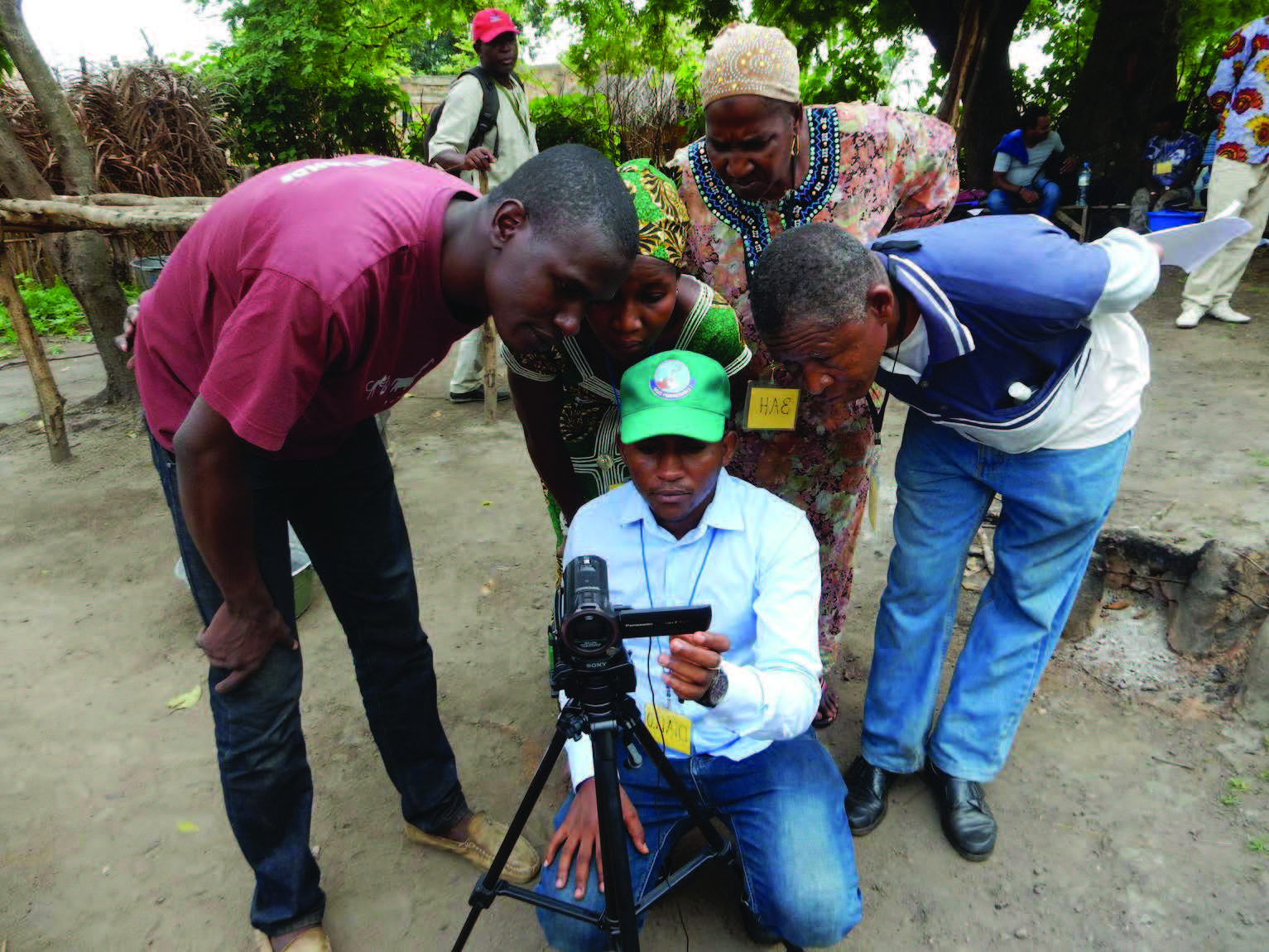

Sometimes called participatory video or digital storytelling, community video is a form of community media that facilitates groups or communities to create, shape, and tell their stories on-screen. It is an accessible, relatively cost-effective medium for empowering communities to develop their own stories and solutions and/or communicate their desires to decision makers (Dougherty et al. 2016; Gandhi et al. 2009). A number of organizations focus on different types of community video approaches, working collaboratively with other public, private, and civil society organizations to improve agricultural practices and livelihoods (Digital Green 2017); promote social justice (InsightShare n.d.); train activists to use videos to expose human rights abuses (WITNESS, 2016); focus on female-centered social or economic issues (videoSEWA n.d.); and enable exchange of and access to quality audiovisual training materials (Access Agriculture 2016). We have studied and implemented various types of community video approaches to promote nutrition, WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene), and nutrition-sensitive agriculture behaviors in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea, India, Niger, Senegal, and Uganda. We share some of our experiences and lessons learned in the following Principles in Practice section. Together with Digital Green, we pioneered the innovative Community Video for Nutrition approach, unique in involving the community at each step: design, production, and dissemination (Granger et al. 2015). With this approach we have successfully promoted a variety of multi-sectoral nutrition-related behaviors.

The process of implementing a community video approach in communities is multifaceted. The first step typically involves participatory formative research to gain an understanding of local practices and contextual realities as well as how certain determinants may promote or hinder adoption of key practices. Short videos are then scripted, directed, and recorded with varying levels of community engagement. Once completed, videos are either screened in neighboring communities or shared with community leaders or decision makers to generate awareness, catalyze behavior change, and spark dialogue between various groups. Aided by the most recent advancements in ICT, videos can be disseminated through any number of formats such as digital video/versatile discs (DVDs), handheld battery-operated mini (pico) projectors, downloadable or streamed visual files from digital platforms such as tablets or mobile phones, or video-sharing websites on social media (Okry, Van Mele, and Houinsou 2014; Tuong, Larsen, and Armstrong 2014).

The success of video as an SBCC tool is largely attributed to its ability to actively engage members of the community through experiential or emotional learning to increase self-efficacy, promote a given behavior, and encourage its adoption. Storytelling through video draws on the idea that individuals learn through observing, modeling, and imitating others’ behaviors, attitudes, and consequences of those behaviors (Bandura 1977).

Social Media

Social media is emerging as a dynamic social change and communication tool increasingly used in many areas of development. Many consider social media simply as a platform on which community and other media can be shared; however, we would argue that the dialogue that social media platforms facilitates should also be considered community media (Berger 2015). A commitment by many governments and private industry to increase Internet accessibility and the rapid growth and saturation of the mobile and smart phone markets has drastically increased access to the Internet, even among very remote and marginalized populations. This phenomenon has facilitated the upsurge in adoption and use of social media platforms. Access to social media enables communities, including policymakers, institutions, social groups, and individuals, to engage in multi-directional conversations. Social media plays an increasing role in development activities not only by spurring social movements and dialogue but also by tracking disease outbreaks and coordinating aid in disasters. A prime example is the use of Ushahidi, an open-source platform that integrates crowd-sourced information from phones, web applications, email, and social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook to provide an up-to-date, publicly available crisis map that can also be used by relief organizations. Ushahidi was deployed after Haiti’s 2010 earthquake and helped link health care providers needing supplies to those who had them (Gao, Barbier, and Goolsby 2011; Merchant, Elmer, and Lurie, 2011). Increasingly, mass media campaigns incorporate social media efforts to enable greater interactivity as well as try to stimulate social movements that can take on a life of their own. Therefore, not all social media can be considered community media. However, as global Internet accessibility and mobile phone reach increase, social media is being used more often, either as a component of, or as a standalone approach for, community engagement, elevating local voices, advocacy, empowerment, and stimulating and supporting social and behavior change efforts.

Building on Lessons Learned

As noted, the evolving nature of community media in a rapidly changing media landscape makes it difficult to pinpoint a singular definition and set of parameters. However, the principles of community engagement, capacity building, contextualization, and sustainability clearly underpin almost all forms of community media. Drawing on these key principles and harnessing community media’s flexibility and fluidity, we have catalyzed community media as a nutrition SBCC tool across several challenging environments. Using case examples from our work in community media, the following section outlines best practices for community media approaches as well as lessons we have learned through implementation in different contexts.

Community Media Principles in Practice

How is SPRING Using Community Media?

In 2012, we began adapting and implementing community media approaches for multi-sectoral nutrition programming in India, and since then we have implemented different models in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea, Niger, Senegal, and Uganda. The following community media case examples synthesize key elements of this SBCC approach to share best practices, challenges, adaptations, and results in the use of community media to change nutrition-related behaviors in a variety of contexts.

Each of the principles may be given more or less emphasis depending on the program and context. The three case examples presented here highlight the community engagement principle and one of the other three principles that was most critical.

The first case example highlights two ways we used distinctive community video approaches in community mobilization in Ghana and Uganda, with an emphasis on the principle of contextualization. Our community video work within multi-sectoral programming in Guinea, India, and Senegal highlights the principle of capacity building. In the Sahel, our community video and radio programming demonstrate the principle of sustainability in a resilience setting. Each case example describes the community media program and details how particular principles were applied and considered.

Contextualization Case Example:

Community Video in Community Mobilization Campaigns

While community media is a tool for community members to share their stories, experiences, and knowledge with neighbors, community mobilization provides a process for community members to work together to improve conditions in their own community. The principles of community media are also present in community mobilization programming, making community media and community mobilization complementary approaches that engage communities to drive behavior change.

Although approaches to, and definitions of, community mobilization are wide and varied, community mobilization programs generally strive to engage and empower community members to plan, implement, and assess projects to improve conditions in their community (Howard-Grabman 2007). These programs often build the capacity of local leaders or organizations to facilitate this process, with resources and/or technical assistance from external facilitators.

SPRING implemented two different community mobilization programming approaches in Ghana and Uganda, and while the program models in each country varied significantly, both embedded community video within community mobilization programming. Each program used community video in an effort to more widely share information,mobilizecommunitiestoact,andpromoteimprovednutrition-related behaviors among individual families and households to improve nutrition outcomes.

SPRING/Ghana—WASH 1,000

In Ghana, we worked with “WASH 1,000” communities, which were communities mobilized through an adapted community-led total sanitation (CLTS) model focused on families with pregnant women and children under two. In addition to building latrines to achieve open defecation free (ODF) status, WASH 1,000 communities promote and adopt key WASH behaviors related to young child nutrition, such as handwashing with soap at critical times for both caregiver and child, safe disposal of human and animal feces, creating safe play spaces, and giving children treated/boiled water.

The WASH 1,000 program strengthened learning and messaging about WASH by developing live dramas, which were recorded on video and disseminated within communities. We identified drama groups who performed in the differentlanguagesspokeninthatregion,andtrainedthemtoproduce dramas promoting key WASH practices using scripts developed by local writers. These WASH dramasareinfiveregionallanguages,andarescreenedinWASH 1,000 communities to support them to achieve ODF status. The videos are disseminated in community-wide evening screenings, followed by discussion and commitment sessions, where families commit to trying or improving one or more of the four behaviors shown in the videos. This work complemented the program’s intense focus on latrine building with other behavioral elements important for the health and nutrition of a WASH 1,000 household.

Participants of our SPRING/Ghana program create a drama to promote nutrition-sensitive water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) practices using a Tippy Tap. For more, please visit here.

SPRING/Uganda—Community Action Cycle

In Uganda, we worked through communities engaged in community action cycle (CAC) programming to promote interest in, and motivation for, improving young child feeding and care behaviors. Community video was a key component in this CAC program, called the “Great Mothers, Healthy Children” campaign.

Through rapid formative research using an emotion-based approach, we identified key emotion-based drivers, such as status and recognition, related to child nutrition and health behaviors in these communities. Because emotions drive behaviors, along with habits, unconscious perceptions, and conscious application of logic and facts, knowing which emotions drive community members’ behaviors was essential to campaign success. After identifying common emotional drivers, we recorded a series of eight testimonial videos with local villagers that particularly appealed to the emotional drivers while addressing key child feeding and care behaviors. The videos included appeals to three target groups of influencers and caregivers—mothers, fathers, and grandmothers—and were disseminated by village health teams (VHTs) using handheld pico projectors in facilitated screenings for community members in each target group. During these screenings, participants made commitments to adopt small, doable actions shown in the videos to improve child feeding and care in their own homes.

SPRING/Uganda and the "Great Mothers, Healthy Children" Campaign

Women gather to watch a video testimonial that uses emotion-based drivers related to child health as part of our SPRING/Uganda “Great Mothers, Healthy Children” campaign. For more, please visit here.

Why Use Community Media in this Context?

There are several reasons these SPRING nutrition programs chose community media, in particular, community video, as a key element of behavior change strategy. Using community video in the community mobilization context strengthened these programs by:

- Motivatingparticipationduringthecommunity mobilization activities

- Helping the program engage the whole household

- Triggering emotions to facilitate behavior change

- Building upon existing popular media and information sharing platforms

Motivating participation during the community mobilization activities: In both SPRING programs, community video generated community interest not onlyinthespecificallypromotedbehaviors, but in ongoing community mobilization activities as well. The combination of a video as a novel communication channel, as well as the involvement of community members in video production, drew community members to attend screenings, change behaviors, and become involved in community mobilization processes. For these reasons, the use of electronic media may have sparked more interest than would more traditional SBCC materials, such as flip charts.

Engaging the whole household: While female attendance at the video screenings was slightly higher in both Ghana and Uganda, videos were viewed by a variety of household members, not just mothers of children under two years of age.

In the two districts in Uganda where the Great Mothers, Healthy Children program was implemented, these videos reached 26 percent of mothers, 20 percent of fathers, and 18 percent of grandmothers of children under two in the implementation villages, with many beneficiaries noting that they shared the information they learned with others. In Ghana, 24,003 people participated in screening sessions in 2016; 45 percent of these participants were male. In these communities, men are the primary household decision makers, so it was important to bring men into conversations around installing household latrines, constructing tippy taps, and other WASH 1,000 key behaviors. We found that men who made commitments during screenings to construct household latrines actually carried out these commitments. In contrast to other SBCC tools that do not always engage the broader community in discussions, the community media approach in both of these programs reached across demographics to bring members of the whole household and community into a facilitated discussion to drive commitments to behavior change.

Triggering emotions to facilitate behavior change: In Uganda, the video testimonials were explicitly designed to draw upon emotional “triggers” around four specific child feeding and care practices identified during the formative research process. The video platform allowed community members to more effectively elicit emotional responses to the target behaviors by speaking directly to their neighbors in testimonials. In focus group discussions, participants repeated emotional drivers such as status and recognition as important reasons for adopting behaviors, showing that the emotional drivers shown in the videos motivated participants.

Building upon popular media platforms: In Ghana, community drama groups are a popular medium for learning new ideas, accessing information, and adopting practices. For this reason, these groups provide a natural platform for community health education partners to share information in WASH 1,000 communities. Capturing WASH dramas on film allowed the partners to take them to many more communities than they could reach with live drama.

Community Engagement Principle: Where in the Process Was the Community Engaged?

Both video approaches involved communities in various aspects of content development, from locally developed scripts to community perspectives and voices in testimonials. In both programs, local community members and groups were actively engaged in the video screenings and discussions following video screenings.

In Ghana, we developed content briefs and engaged local writers to draft scripts. We were aware of barriers to changing WASH behaviors from what had been happening under CLTS and we used that information from the community in the content points given to the scriptwriters. The scripts were refined in collaboration with local drama groups, who were given artistic license in how they acted out the script. The dramas were then recorded by a production team so that they could be shared more widely. Local government staff, including district environmental health officers and district-level community development and social welfare officers, disseminated the videos and, with community leaders, facilitated community dialogue around the video and practices. Local government staff also conducted follow-up visits to households who had made behavior change commitments. Community leaders, such as chiefs, local assembly members, community volunteers, and local champions of CLTS efforts, were involved in the mobilization process in support of WASH 1,000 programming and encouraged community members to commit to trying the improved practices. Though the process of developing scripts and producing videos was carried out by a local production company familiar with the area and culture, the community as a whole participated in screening, discussion, and commitment sessions.

In Uganda, community members and community leaders were involved in focus groups during the formative research process to identify key determinants and emotional drivers of behaviors. Select community members, identified by local government partners, gave their testimonials in videos, which provided an opportunity for these community members to tell their stories to their neighbors. VHTs and community action group (CAG) leaders had the important role of disseminating the videos, facilitating discussions and commitment sessions, and following up with community members to promote behavior change. Community leaders also attended group discussions and screenings. As in Ghana,communitymembersingeneralwerelessinvolvedspecificallyin the production of the videos, but many community members participated in screening, discussion, and commitment sessions.

Contextualization Principle: How Was The Approach Contextualized?

The Uganda program created highly contextualized videos by conducting participatory formative research, using community members’ testimonials, tailoring videos to different groups, and disseminating them through established platforms. Our formative research identified practices as well as emotional drivers relevant to these communities, which helped messages resonate with community members. The key drivers identified through this process were status in the community, recognition by community members, self-fulfillment, and achievement. Video development drew on these hot-button issues to incentivize change in both behavior and beliefs. In addition, video content came directly from community members themselves, in the form of recorded testimonials. While the testimonials were given in response to guiding questions, the questions were open-ended to allow community members to provide genuine, organic responses. The videos were also tailored to two groups—primary caregivers (mothers) and supporters and influencers (fathers and grandmothers). Videos for mothers included testimonials from mothers, and videos for supporters and influencers included testimonials from elder women (grandmothers) and men (fathers and grandfathers). These tailored videos reflected the different rolesthesegroupsplayinchildcareandfeedingdecisionstomake the content relatable to different viewers. VHTs screened the videos in three separate groups of mothers, fathers, and grandmothers to promote dialogue. The VHTs were established sources of health information in the communities. Building upon this existing community structure helped strengthen the credibility of the promoted messages.

The Ghana program used the popularity oflocaldramastoleverageacceptability,butbuiltuponthisplatform by recording dramas to expand their reach. While storylines were based on local knowledge, practices, beliefs, and norms, the program also engaged local drama groups to refine scripts, filmed the dramas in local communities and in different local languages, and pre-tested the dramas in the communities. This process allowed nutrition and health messages to be adapted and made relevant for,andacceptedin, the local context, while ensuring technical accuracy of the information.

Results

In Ghana, data from the 135 communities that participated in 2016 show high attendance in video dissemination sessions, good participation, and evidence of behavior change. The commitment sessions resulted in 3,601 families committing to try one or more of the new or improved prioritized WASH behaviors. Early monitoring indicates that about 64 percent of those who committed to behaviors have fulfilled their commitments. Approximately two-thirds of participants committed to improved handwashing, one-half committed to improved latrine use, one-half committed to providing a clean play space free of animal feces for their children, and one-third committed to safe drinking water.

The SPRING/Ghana program also built the capacity of local drama groups, strengthening a platform that can be leveraged in future health programs. By providing drama groups with training in video production and in adapting scripts to the local context, the program built these groups’ capacity to incorporate specific health behavior change messages into this popular media form.

The program in Uganda also had high attendance and participation, and qualitative evidence shows high acceptability and motivation to change behaviors. In the two districts where the program was implemented, videos reached 14,317 people in 216 villages, including 26 percent of all mothers of children under two who live in the targeted villages. The videos also reached 20 percent of fathers, as well as 18 percent of grandmothers of children under two in these villages. In addition, many beneficiaries said that they shared the information they learned with others.

Through focus group discussions, we assessed changes in knowledge and attitudes in the communities and determined if the project design was appropriate, sustainable, and successful in reaching the target population. Mothers, fathers, and elders reported changed behaviors, with the greatest change in behaviors around breastfeeding and care seeking for sick children. A focus group participant in Ntungamo district said, “I found out that when a child is sick, you should not run to the herbal doctors but you should rather talk to your husband and find ways possible to take your child to the hospital.” The assessment also found that participants demonstrated strong recall of key messages from the videos and demonstrated an eagerness to change behavior. In addition, the locally produced videos motivated participation. A VHT member in Uganda noted, “When they found that the video was made bypeopleofthesamesubcounty, they said that means that we are also important people we can do something and other people come to see it. So it brought them an interest to come and watch that video.” Finally, the program strengthened VHTs’ nutrition training and provided them with a new and helpful SBCC tool.

Challenges and Considerations

Operationally, both countries had unforeseen challenges unique to their dissemination strategy. While SPRING/Ghana disseminated videos through local government officers using government-owned video vans, SPRING/Uganda disseminated videos through existing local organizations using procured pico projectors. As a result, SPRING/Ghana’s primary challenges were related to partner and resource coordination, and SPRING/Uganda’s primary challenges were related to equipment procurement. These challenges show that working through existing local partners and procurement processes are key considerations when developing a community video dissemination strategy.

SPRING/Ghana’s challenges with partner coordination reveal a strong need for defining roles and responsibilities of all partners early on in the implementation process. For example, it was not clear to partners from the beginning that follow-up visits were needed for the activity, which hampered planning for adequate resources for follow-up visits. To consolidate resources and save time, SPRING/ Ghana is working to integrate monitoring and follow- up with other ongoing activities.

SPRING/Uganda’s operational delays included insufficient distribution and quantity of pico projectors, as well as issues with charging the projectors, requiring the additional procurement of solar panels. In addition, video development was a longer process than expected, taking time away from implementation. These challenges underscore the importance of allowing adequate time for equipment procurement, distribution, and testing when developing a community video strategy.

Conclusion

In both Ghana and Uganda, community video was an innovative and effective SBCC medium that complemented existing community mobilization activities. These efforts worked in concert to engage and empower communities through multiple levels and channels to affect their own change to improve health outcomes. Bothprogramsengagedcommunitiestovaryingdegreesinvideoproduction, but community participation was inherent in the overall context of ongoing community mobilization activities. Both programs made concerted efforts to ensure that the videos were highly contextualized, appropriate, and acceptable to the communities. While both programs experienced operational challenges, they were effective in promoting behavior change. Contextualization is akeyaspectofcommunitymedia,andisshowcasedinthese two program examples. Community media was used as a tool to help achieve community mobilization program goals by amplifying contextualized stories and messages to spur health and nutrition behavior change.

Capacity Building Case Example:

Community Video in Multi-sectoral Programs

Increasingly, evidence shows that a number of diverse factors affect a family’s nutrition, including consumption of a nutritious and diverse diet; access to quality health services; optimal water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH); access to quality education; and others (USAID 2014). With wide-ranging determinants of nutritional status, programs that seek to sustainably improve nutrition outcomes must tackle not only nutrition-specific factors related to immediate causes of malnutrition, such as infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices and micronutrient fortification, but must also improve nutrition-sensitive factors related to underlying causes of malnutrition—for example, WASH and improved agriculture techniques (USAID 2014).

SPRING has routinely integrated WASH behaviors into our MIYCNprogrammingglobally,and considers hygiene practices intrinsically linked to nutrition outcomes. Promotion of WASH practices like handwashing with soap at critical times, clean play spaces free of human and animal feces, drinking clean water, and food safety and hygiene are commonly included in our programming.

In addition, we are working to make agriculture more nutrition-sensitive in many countries by supporting agriculture partners in identifying, prioritizing, and promoting nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices. Nutrition-sensitive agriculture addresses the underlying causes of malnutrition by 1) improving food production, or the availability, quality, and diversity of the food a household consumes; 2) providing agricultural income for food and non-food expenditures, such as health services; and 3) empowering women, which can promote household spending on food and health care as well as increase women’s time and capacity to care for themselves and their young children (Herforth and Harris 2014; SPRING 2014a; SPRING 2014b; SPRING 2014c). Though nutrition-sensitive agriculture is not a new concept, little is known about which specific nutrition-sensitive practices are most effective in improving nutrition; as a result, agriculture programs have had difficulty integrating nutrition-sensitive practices into their programming.

We have implemented a number of multi-sectoral nutrition programs around the world, adapting different programming approaches and tools to each context. Recognizing the ability of community media to engage communities, share multi-sectoral nutrition information, and promote behavior change, we have implemented community video programs in a number of countries, including Guinea, India, and Senegal.

Community Video for Nutrition in India

SPRING and Digital Green (DG) first tested a multi-sectoral community video approach in India in 2012 to respond to demands for greater nutrition knowledge and health education in rural communities, and to test alternative and innovative SBCC approaches. In a 12-month pilot program in the Keonjhar district of Odisha, India,SPRING and DG tested the feasibility of adapting DG’s community video model, which had previously been shown effective for promoting improved agricultural practices, to promote MIYCN and WASH practices. The model built on DG’s existing agricultural extension platform, working with local partner Voluntary Association for Rural Reconstruction and Appropriate Technology (VARRAT), to support the development of community-led participatory videos. This process produces and disseminates videos locally in remote villages using handheld cameras and mobile pico projectors and follows the specific Community Video for Nutrition approach. ( For more on the SPRING/DG community video for nutrition approach, please see: www.spring-nutrition.org/publications/series/community-video-nutrition-guide.) The results of the feasibility study, which was conducted by the International Food Policy Research Institute, found that the community video approach was highly accepted in the community, feasible tointegrateintoexistingprogramming,andapromisingapproach topromoteMIYCN practices (Kadiyala et al. 2014).

SPRING/India

SPRING is working to promote nutrition behaviors through DG’s agriculture extension community video model in India. For more on our work in India, please visit here.

12-month pilot program in the Keonjhar district of Odisha, India, SPRING and DG tested the feasibility of adapting DG’s community video model, which had previously been shown effective for promoting improved agricultural practices, to promote MIYCN and WASH practices. The model built on DG’s existing agricultural extension platform, working with local partner Voluntary Association for Rural Reconstruction and Appropriate Technology (VARRAT), to support the development of community-led participatory videos. This process produces and disseminates videos locally in remote villages using handheld cameras and mobile pico projectors and follows the specific Community Video for Nutrition approach. ( For more on the SPRING/DG community video for nutrition approach, please see: www.spring-nutrition.org/publications/series/community-video-nutrition-guide.) The results of the feasibility study, which was conducted by the International Food Policy Research Institute, found that the community video approach was highly accepted in the community, feasible tointegrateintoexistingprogramming,andapromisingapproach topromoteMIYCN practices (Kadiyala et al. 2014).

Following this successful proof-of-concept study, we continued to support the work of VARRAT and DG to promote nutrition behaviors through their agriculture-centric program model.Currentlyweareproviding technical expertise to a randomized control trial on the community video approach for nutrition and nutrition-sensitive agriculture in India funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, in partnership with DG, the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, VARRAT, and Ekjut. The study will significantly contribute to the evidence base on this innovative human-mediated technology approach by providing evidence of impact on nutrition and other outcomes related to multi-sectoral programming.

SPRING/Guinea

SPRING/Guinea is adapting and testing the community video approach to promote nutrition specific behaviors and nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices. For more on our work in Guinea, please visit here.

Community Video in Guinea and Senegal

Following the initial pilot in India, we adapted this Community Video for Nutrition approach in Guinea and Senegal to continue to promote not only nutrition-specific but also nutrition-sensitive behaviors in multi-sectoral programs. Our programs in Guinea and Senegal strengthen the capacity of local networks and organizations that are not focused on health, such as community- based organizations, agricultural value chain actors, and market actors, but who are willing to promote nutrition and nutrition-sensitive agriculture in their communities.

Our primary goal in Guinea is to contribute to improving dietary diversity among households with pregnant and lactating women and children under the age of two in Faranah prefecture. To improve dietary diversity, we take a multi-sectoral programming approach, with community videos that promote nutrition-specific MIYCN behaviors, such as exclusive breastfeeding and diverse complementary foods, as well as nutrition- sensitive WASH and agriculture practices, such as drying and storing sweet potato leaves to ensure access to vitamin A–rich food during the dry season. Initially disseminated through women’s community groups, videos are now being used by agricultural entrepreneurs within a market-led project to promote the uptake of nutrition-sensitive agriculture technologies and practices.

SPRING/Senegal is working with partners to by operating through existing health, agriculture, and food security programs and using community video and radio. For more on our work in Senegal, please visit our SPRING/Senegal page.

In Senegal, we use video to deliver both nutrition-specific MIYCN and nutrition-sensitive WASH and agriculture messages that complement and reinforce one another in three regions of the country: Kaolack, Fatick, and Kaffrine. Working with nutrition, agriculture, health, and economic growth partners, the program seeks to raise awareness and adoption of good nutrition-related practices through multi-sectoral SBCC and capacity building approaches, including community video and community radio.

Why Use Community Media in this Context?

These multi-sectoral programs chose community media as a key element of their behavior change strategy because of its ability to:

- Leverage the reach of existing extension platforms and strengthen IPC for nutrition

- Integrate into existing programs and platforms, across sectors, and across partners

- Address complex multi-sectoral issues in integrated storylines

- Fulfill a need for community-level systems to provide access to health information

Leveraging the reach of existing platforms and strengthening IPC: Existing agriculture and health programs often have extensive reach into communities. We recognized an opportunity to improve nutrition outcomes by leveraging the reach of these existing programs and strengthening the nutrition sensitivity of the information they provide.

We conducted a nutrition assessment in Guinea in 2015, examining the impact of Ebola on health and agricultural services, agricultural production, food security, and nutritional status.

The assessment found that the network of agriculture extension workers had limited resources to effectively share information and teach improved practices. In addition, community members, leaders, health workers, and extension agents readily identified nutrition as a challenge faced by the population and were enthusiastic about improving community nutritional knowledge and practices. SPRING/Guinea chose to use community video in this program to both build on these existing platforms and to improve IPC and small group discussions, ultimately promoting household-level practices around production, handling, and preparation of foods to improve dietary diversity.

Using Community Radio to Amplify Community Video Content

In both Guinea and Senegal, community radio has also been introduced as a complementary information channel to reinforce and amplify community video content. We identified six local radio partners in Senegal to broadcast spots containing key nutrition-sensitive farming, hygiene, nutrition, and gender messages throughout the project area. We worked with these radio stations in 2016 to promote nutrition-sensitive agriculture messages on air through interviews and news stories. This content was complemented by 21 talk-show style radioprogramsthatfeaturednutrition-relateddiscussionledbyinfluential community members, local government unit health workers, and representatives from agricultural partner networks. The DJ served as the talk show host after being coached by SPRING staff prior to each interview. Though most were pre-recorded and aired later, some of these radio programs were aired live. During these live programs, listeners were encouraged to call in and ask the invited community influencers questions. Live programs were highly appreciated and overwhelmingly preferred to pre-recorded broadcasts because of the ability of community members to call in.

The Guinea program also incorporated community radio to complement its existing community video work and support the new Feed the Future program partners. Working through Farm Radio International, we built the capacity of four local radio stations in Mamou and Faranah prefectures of Guinea to develop effective interactive radio programming to support the uptake of nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices. Each program focuses on education and building awareness about thetechniquesandrelevanttechnologies,whileincorporatingcommentsfrom local farmers and experts. The strategy is to engage community radio stations in creating radio content to promote the use of new agricultural technologies and to reinforce the nutrition and hygiene messages developed for video. Introducing radio allowed us to extend the reach and increase the potential impact of these communications by broadcasting messages to a wider geographic area, in multiple local languages. Evidence suggests that multipronged communications strategies are more effective than using a single channel (Lamstein et al. 2014). Since radio is a trusted form of communication used widely in agriculture development, it is a natural tool for reinforcing and amplifying community video communication efforts in Guinea and elsewhere.

Integrating into existing programs, across partners and sectors: In India, we found that agriculturalists can share videos about nutrition without having to become nutrition experts themselves, helping community video activities for nutrition to integrate into established programs using existing program staff. We selected community video as an SBCC approach in Guinea and Senegal because—

- there is evidence showing the effectiveness of this approach

- these countries engage in multi-sectoral programming that allows work across agriculture and health platforms

- we had a mandate to work through local partners in these countries.

Community video provides a tool for implementers to work with communities to develop context-specific and technically accurate content that can be disseminated through various partner-led efforts. Because the community video model can be adapted to a number of platforms and sectors, allowing programs to share nutrition information with or without nutrition experts on staff, it could be integrated readily into partner programs.

Addressing complex multi-sectoral issues in integrated storylines: Our formative research in Senegal revealed many barriers to accessing and consuming nutritious foods. Community video promotes optimal nutrition and hygiene practices while also addressing underlying gender considerations, such as portrayingcouples’communicationarounduse of household resources to achieve better nutrition for all family members. Using video as a communication channel showcases positive role modeling of recommended behaviors to help stimulate behavior change. This innovative storytelling model facilitates communication among peersatthevillagelevel, and addresses multi-sectoral factors (nutrition, health, hygiene, and gender) in a single presentation.

Fulfilling a need for community-level systems to provide health information: In Senegal, as in most countries where we work, there are no community-level systems that provide access to information about nutrition-sensitive agriculture or other health-related practices. For this reason, we chose community video as one component of a larger SBCC strategy that includes community radio as well as a number of community engagement activities. The use of a broad approach, working through agricultural and health networks, reinforces the promotion of nutrition, WASH, and agriculture messages and products, ultimately reaching a much greater, more diverse audience.

Community Engagement Principle: Where in the Process Was the Community Engaged?

These community video programs engage the community at multiple steps in the process, with local organizations and extension workers participating in all aspects of production. Videos feature farmer mothers, health workers, and other community members speaking about their personal experiences related to key nutrition practices. Volunteers from the community are trainedtoconductvideodisseminationsandhomevisits,andattendmonthlycoordination meetings aswellasrefreshertrainings. Members of village-based groups (farmers groups, women’s groups, and others) attend regular meetings during which they view and discuss a video on a specific topic related to hygiene, nutrition, and/ or nutrition-sensitive agriculture. We work with several different groups and partner organizations in Senegal, including women’s cooperatives and producer networks. In India and Guinea, we workprimarilywithwomen’sfarmersgroups.

Community facilitators are drawn from both male and female community members; some are grandmothers, some are traditional birth attendants, and others are members or officers of local agriculture groups. All are considered formal or informal leaders in their community. Our staff and/or our partners identified these individuals because they are considered to be people that other community members trust and will listen to. In Guinea, 16 community volunteers from four villages surrounding the prefectural capital city of Faranah were initially trained in MICYN and hygiene, community video dissemination using the pico projector, monitoring behavior change, and reinforcing messages during home visits. Each volunteer has recruited two groups of 15 women who are pregnant and/or have a child under two years old. These women have agreed to participate in one video dissemination meeting per month and receive a home visit from a volunteer after each meeting. Each woman has identified an “influencer” (usually her mother-in-law or husband) who attends a separate screening of the same video so that different members of households and communities are engaged in the nutrition conversation. In Guinea, we initially invested in developing this community video pilot to build an SBCC platform for use by its local implementing partner, Winrock International, and other Guinea-based Feed the Future programs funded by USAID interested in promoting improved agricultural practices, new technologies, and related nutrition and hygiene behaviors.

Capacity building is central to the community video approach and is especially crucial when implemented in a multi-sectoral context with content from different sectors. Working with local partners, we are enhancing existing systems to build agriculture extension workers’ and other cadres’ capacity to share nutrition information. By training and involving many partners in implementation, we transfer capacity to implement the community video process to both local and international organizations, that can continue to support community video programs beyond the life of SPRING.

Beginning in India, we deliberately positioned agriculture extension workers alongside traditional health workers to enable these groups to work collaboratively to produce nutrition-focused video content.Trainingsforcommunityfacilitators in India alsoincludecommunity health workers to ensure that video messages are consistent with those provided through traditional health education platforms. Additionally, joint trainings help link the community video program and community volunteers with existing health services and facilitates health workers’ buy-in and support for the program.

In addition to initial trainings on video production, dissemination, and technical information, the Community Video for Nutritionmodelincludesmonthlydissemination preparation meetings. Held by partner organizations, these are half- or full-day meetings with all local facilitators to view new videos and address questions about video content. SPRING/ Guinea recently invited an expert from the Ministry of Health to one such meeting introducing a new community video on exclusive breastfeeding. The expert provided technical background and answered questions from disseminators, many of whom are drawn from the agriculture sector. These meetings help facilitate multi-sectoral linkages and involve multiple local actors in the community video process, facilitating understanding and buy-in of the program.

In Guinea, we work closely with Winrock International as well as with Institut Supérieur Agronomique et Vétérinaire (ISAV), the local agriculture university. Collaborating with ISAV has helped build capacity to implement the approach through a local institutional mechanism; members of two local radio stations and several local NGOs havealsoparticipatedintrainingsandactivities. We are also exploring potential partnerships with local agricultural input suppliers, who may be willing to invest in community video activities to increase demand for their nutrition-sensitive agricultural products while promoting MIYCN, hygiene, and nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices.

SPRING/Senegal identified several members of different communities to develop local video production hubs to produce new videos for programs beyond the life of SPRING. In addition, SPRING and DG have provided community video production training to partners including local community radio stations and agriculture partners such as Caritas, Symbiose, FEPROMAS, and ADAK, and have trained partners working in the areas of agriculture, horticulture, animal husbandry, agro-processing, and community health to disseminate community videos, including using pico projectors and facilitation skills for group dissemination. Giventhediversityoftechnicalpartnersthereisoftena need to build additional technical capacity in each of the various technical areas.

Results

Findings from the initial community video pilot in India have shown the community video approach to be an acceptable and effective model to change household MIYCN behaviors and stimulate social change (Kadiyala et al. 2014). We are also supporting a randomized control trial to assess the impact that promoting nutrition-sensitive agriculture behaviors through community video, with and without nutrition-specific MIYCN and hygiene behaviors, can have on nutrition and health outcomes.

The partners and communities in Guinea and Senegal were eager to continue participating in community video programming. SPRING has learned that establishing video hubs is a good way to ensure sustainability of the community video approach. In Guinea, Winrock International has approached the video production teams trained by SPRING to develop 14 new community videos on nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices and is considering reinforcing messages through SPRING-supported community radio stations as well. In Senegal, members of our video production hubs have met with Télévision Futur Média, a Dakar-based TV station, and AZ ACTU, a Senegalese communications agency to discuss future collaboration. Additionally, new USAID projects in the region have expressed interest in working with the established hubs. We also conducted an evaluation to compare areas where we worked only with agriculture partners to influence the food environment to those where we complemented that intervention with community video. In the community video villages, dietary diversity went from 18.3 to 63.9 percent; in control villages, it remained about the same (30.2 to 36.4).

Challenges and Considerations

One advantage of this approach is that production is typically a fairly rapid process. In India and Guinea, shooting one video usually takes two days (one day of preparation and one day of shooting), and editing adds an additional day. However, production has required more direct support in Senegal compared to other intervention areas, partially due to a large number of stakeholders and different levels of baseline knowledge. When working with stakeholders from many sectors, there is often a need to build additional technical capacity in health, agriculture, and other domains, in addition to video production training.

In each new implementation area, it has also proven challenging to find a balance between supporting production teams and allowing them to work autonomously to ultimately enhance the sustainability of the approach and allow it to be more community-led. This challenge differs according to literacy levels of volunteers, and experience/training of local staff and partners. In each program, we build capacity to create and disseminate videos, but also to have the technical understanding needed to develop videos about nutrition and nutrition-sensitive agriculture. However, nutrition-sensitive agriculture is an emerging area, and evidence is still being generated on the most effective interventions and the most appropriate behaviors to target. We have developed two two-day orientations for nontechnical local staff, one for nutrition and the other for nutrition-sensitive agriculture, and continue to further refine complex nutrition-sensitive agriculture concepts into practical and concrete guidance accessible to low-literacy populations.

Conclusion

Acknowledging the range of determinants that affect nutrition, we recognize the need for continued programming and research that focuses on multi-sectoral approaches to improve health outcomes. We recognize that people in the communities in which we work don’t live their lives siloed in health or agriculture sectors but rather in families and villages, where all the problems of life converge. Our work in community video started with integrating nutrition content into an existing agriculture program and has expanded to include the promotion of agriculture, MIYCN, hygiene, and nutrition-sensitive agriculture practices in a single package. While multi-sectoral programming can be challenging, it can also be equally efficient and arguably more effective. Our experienceshaveshownthatcommunityvideoisavaluable tool for engaging communities and building the capacity of multiple partners to “connect the dots” and promote optimal nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive behaviors in their programs and the communities they serve.

Sustainability Case Example:

Community Media in a Resilience Setting

Africa’s Sahel region is characterized by harsh climate conditions, which contribute to recurrent food crises and high rates of severe acute malnutrition among children. Communities experience frequent shocks, including conflict, drought, and food shortages, which necessitate health behavior change approaches that are flexible and tailored to this resilience context. With 44 percent of children under five stunted in Niger and 35 percent in Burkina Faso, there is a need for approaches that can reach large numbers of people quickly, in order to accelerate efforts to improve nutrition. In addition, addressing the nutrition, health, and livelihoods needs of communities in the Sahel requires rapid and flexible communication approaches that can be adapted to the community context. SPRING began supporting nutrition programming in Niger and Burkina Faso in 2014, working with local partners to introduce and scale up SBCC activities with a focus on maternal, infant, and young child nutrition (MIYCN) and hygiene.

Niger Community Video

Community videos on optimal MIYCN and hygiene practices are produced by local video production hubs and disseminated in existing community groups by community volunteers.

SPRING/Niger—Community Video

In Niger, SPRING and Digital Green (DG) have collaborated to support community-led videos encouraging optimal MIYCN and hygiene practices. This work builds on an earlier Community Video for Nutrition proof-of-concept study in India. The Community Video for Nutrition program model was adapted for the Nigerien context and rolled out in partnership with three USAID projects: the Resilience and Economic Growth in the Sahel – Enhanced Resilience Program (REGIS-ER); Livelihoods, Agriculture, and Health Interventions in Action (LAHIA); and Sawki. Partnerships later expanded to include another USAID project, one UNICEF/European Union–supported project, and the Regional Health Directorate.

Community videos in Niger are currently produced by four video production “hubs.” These hubs are run by community members and/or local organizations who create videos featuring their families and neighbors demonstrating recommended MIYCN and hygiene practices in their households. The videos are then disseminated by community volunteers using portable, battery-operated pico projectors at screenings during existing mother-tomothersupportgroups, husbands’ schools, adolescent safe spaces groups, and savings and loan groups organized by various community partners. Working with these partners, we have scaled up the intervention, from 20 villages during the pilot in 2015, to 248 villages in 2017 in both the Maradi and Zinder regions.

SPRING/Burkina Faso—Community Radio and Community Video

In Burkina Faso, we first collaborated with Development Media International (DMI) to produce and disseminate a series of 11 radio spots and 22 live radio drama “outlines”— all focused on key MIYCN and hygiene practices, produced in three different local languages. The content for each spot and radio drama was based on formative research, and each spot was tested with the intended audience. The project also trained staff from the seven participating community radio stations, covering all eight regions in USAID’s zone of influence in Burkina Faso. The program employed a “saturation plus” approach, which included a combination of local language radio spots produced by DMI’s creative team, each being aired at least 10 times a day over the course of two weeks, in combination with aseriesofcomplementaryliveradiodramas. DMI developed the radio drama “outlines” in French; these were shared with participating radio stations and then adapted and produced using local radio talent in the local language. DMI estimated the potential radio listeningaudienceatover3.4 million people living in the eight provinces in the zone of influence.

Burkina Faso Community Video and Radio

Our community radio program in Burkina Faso focuses on empowering local radio stations to produce radio spots and dramas promoting MIYCN and hygiene practices in local languages and complements a similar community video approach adapted from Niger.

For more information about our community media programs in the Sahel, please visit SPRING/Sahel.

We also adapted the community video approach used in Niger to the Burkinabe context and have scaled up the approach over the last year to 90 villages in three regions of Burkina Faso, working with partners REGIS-ER, the Victory against Malnutrition Project (ViM), and Families Achieving Sustainable Outcomes (FASO). We selected one community radio station to be trained as a video production hub and identified and trained two additional video hubs in other regions.

Why Use Community Media in this Context?

We conducted a landscape analysis in 2014 on SBCC-related activities in Niger and Burkina Faso (Rennie et al. 2014). Based on the findings, community media approaches were selected as a priority area of focus to promote MICYN and hygiene during the first 1,000 days in the Sahel region. The landscape analysis indicated that innovative,lowcostmediatechnologiescould help spread information in remote, “media dark” areas unreachedbytraditionalmedia,andthatprograms needed careful design to tackle some of the entrenched social and cultural norms affecting nutrition. The Sahel assessment made it clear that the resilience context was a crowded space, calling for extensive coordination and harmonization among partners at the regional level. Additionally, community media models were preferable in this context because of their innate flexibility, which could potentially allow programs to more rapidly share information during shocks.