Results of a Midline Assessment - September 2016

Background

Micronutrient powders (MNP) are one of the few interventions that address multiple micronutrient deficiencies simultaneously and contribute to anemia reduction in young children from six to 23 months of age. While the efficacy of MNP is well established, few studies have looked at their effectiveness, leaving program implementers with limited documented experiences to guide their efforts. To address this gap, the Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutritional Globally (SPRING) project is piloting MNP distribution in Namutumba district, Uganda. This pilot is part of a larger effort by the Ministry of Health to explore options for MNP distribution. The goal of SPRING’s research is to provide country-specific evidence on performance, measured by coverage and adherence, and cost-effectiveness of two delivery mechanisms.

Based on formative research, SPRING supported the development of a national social and behavior change communication (SBCC) strategy that includes communication tools (e.g., radio spots, reminder calendars). National-level training-of-trainer participants carried out additional trainings at the district level to train implementers, including health workers, district personnel, and village health teams (VHTs). MNP distribution takes place through the health facility system, where MNP are distributed by health facility staff, and community-based efforts, where volunteer VHTs distribute MNP directly to caregivers. In March 2016, SPRING officially launched the pilot program in Namutumba.

Methodology

This report reviews experiences with the MNP program, three months after initial distribution, through a series of interviews with 64 health workers, VHTs, and caregivers. Respondents came from the pilot’s facility and community distribution arms and included caregivers who do and do not give MNP to their children. The goal of this midline review is to identify successes and challenges in the pilot so far, identify areas of improvement for SPRING, and highlight issues that SPRING should explore in endline research efforts.

Results

The review found that implementation of the MNP pilot in Namutumba district is going well. Communities are aware of MNP and have generally positive feedback and experiences. Caregivers know how to use MNP appropriately and encourage members of their community to also use MNP. However, there are reports of negative side effects and challenges to receiving refills prove to be a barrier for continued use. SPRING will need to address both in the remainder of the pilot. Finally, health facility staff report noticeable changes in their workload that will complicate efforts to continue providing quality counseling.

Efforts to improve the MNP program should focus on addressing those challenges that have kept caregivers from giving MNP to their children, on preventing caregivers and their children from dropping out of the program, on increasing continued use of MNP beyond the first packet received, and on strengthening supervision to distributors, through the following approaches:

- Increase support for regular and continued MNP distribution through existing health facility outreach activities to expand access to MNP in the facility arm

- Provide continued training for distributors, including refreshers on the use of monitoring tools and increased focus on the issue of refills

- Expand current communications activities targeting caregivers to include a focus on accessing refills

- Target men and other community members as MNP enablers and potential motivators for continued MNP use in the household

- Provide VHTs with guidance on how to reach out to households more effectively

- Monitor and build on existing supervision activities

- Continue to address negative perceptions and side effects.

This activity also provides insight to key areas that will affect any national MNP program in Uganda. Based on this review, the Micronutrient Technical Working Group (MN-TWG) should discuss—

- adapting the training program for distributors

- expanding the role of VHTs in MNP programming

- addressing the increased workload of facility-based distributors.

Further work is needed to explore the cost implications of MNP delivery, to understand supportive supervision methods for MNP, and to integrate MNP into infant and young child feeding (IYCF) programs effectively. Reviewing progress during the early stages of a pilot allows for program improvement and course correction, which will, hopefully, increase the effectiveness of the MNP distribution as a whole. By documenting these findings, the SPRING team hopes to share its experience with other stakeholders in Uganda, as well as the global MNP implementation community.

Introduction

Micronutrient Powders Are an Effective Method for Tackling Anemia

Nearly one-half of children worldwide suffer from anemia, causing cognitive and developmental issues that can follow them into adulthood (Stevens et al. 2013; Walker et al. 2007). Iron deficiency is the leading contributor to the nutritional causes of anemia, and iron deficiency anemia is the most common cause of years lived with disabilities (Stevens et al. 2013; Stoltzfus, Mullany, and Black 2004; WHO 2001; Global Burden of Disease Pediatrics Collaboration 2016). Deficiencies in vitamin A, B vitamins, and zinc also contribute to the problem of anemia, and these are important micronutrient deficiencies to address in their own right (Christian and West 1998; Koury and Ponka 2004; Sim et al. 2010; West, Gernand, and Sommer 2007).

Micronutrient powders (MNP) are among the few interventions that address multiple micronutrient deficiencies simultaneously and can reduce anemia and improve iron status in young children from six to 23 months of age. A systematic review of trials of MNP found that their use decreased anemia by nearly one-third and iron deficiency by one-half (De-Regil et al. 2011).1 MNP consist of a single-dose sachet of vitamins and minerals2 that can be added to young children’s food immediately before consumption. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends their use in situations where more than 20 percent of children suffer from anemia (WHO 2011). While the efficacy of MNP is well established, few studies have looked at the effectiveness of MNP distribution, leaving program implementers with limited documented experiences to guide their efforts.

Uganda Is Piloting the Use of MNP for Possible Scale-Up

Nearly one-half of all children under five in Uganda are anemic, and rates rise to over two-thirds for children in the east central region of Uganda (Uganda Bureau of Statistics and ICF International 2012). Anemia prevention and control activities fall under the Ministry of Health (MOH), with facility-level services provided by health workers and facility-based village health team (VHT) volunteers, while community-based VHTs provide community-level services. Facility-based health assistants provide supervisory support to VHTs.

The country is developing a national anemia strategy incorporating other anemia-related policies and strategies. Tasked with developing micronutrient guidelines for the country, the MOH-led Micronutrient Technical Working Group (MN-TWG) identified the need for more information on MNP implementation to inform the ministry’s deliberations on potential scale up. The MOH organized a group of interested MN-TWG members to participate in a pilot project. The United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), and the USAID-funded Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations for Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project took on implementation roles, with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) providing monitoring and evaluation support and technical guidance.

Members of the MN-TWG worked together with national and district-level stakeholders to develop a national training-of-trainers (TOT) plan and associated tools. National-level TOT participants carried out additional trainings at the district level to train district-level implementers, including health workers, district personnel, and VHTs. Partners provided logistical support to these trainings, but they were conducted by government staff using the national TOT plan and materials.

Each partner is taking a different approach to MNP distribution in the Ugandan context and assessing different aspects of programming to inform MOH plans for national delivery of MNP. UNICEF is monitoring district-level distribution, WFP is studying the impact of MNP on biological outcomes, and SPRING is focusing on cost-effectiveness of MNP distribution using different delivery channels. The MOH launched the MN-TWG pilot activities in December 2015. UNICEF’s work is ongoing, while the WFP pilot ended in July 2016. SPRING’s pilot ends in November 2016. All partners plan to share findings from the pilot process in early 2017.

Formative Research Used to Inform National SBCC Strategy for MNP

Social and behavior change communication (SBCC) is used to improve child nutrition knowledge and skills, as well as increase demand and motivation for improved complementary feeding practices, including use of MNP. In collaboration with researchers from the University of British Columbia, the MN-TWG carried out formative research to assess acceptability of MNP in Uganda and inform the design of MNP packaging. In addition, SPRING conducted formative research to identify key messages for MNP decision makers, including mothers, fathers, and grandmothers (SPRING 2014).

Based on these activities, SPRING supported the development of a national SBCC strategy (Uganda Ministry of Health et al. 2015), including communication tools (e.g., radio spots, reminder calendars). The communication plan is focused on creating an enabling environment promoting acceptance of MNP, explaining the supply and refill process for continued use of MNP, creating informed demand among caregivers and influencers, and ensuring proper and safe use of the product at home, including related infant and young child feeding (IYCF) behaviors.

SPRING Pilot Investigates Two Delivery Mechanisms

High rates of acute malnutrition in recent years have made nutrition a priority issue for district government and partners in Namutumba district (east central Uganda). A recent study estimates that of children 6–23 months old in Namutumba, 27 percent are stunted and 84 percent suffer from anemia. As one of the pilot implementing partners, the SPRING project is distributing MNP in Namutumba district to provide evidence on—

- comparison of coverage and adherence3 performance of two delivery mechanisms

- cost analysis and a cost-effectiveness comparison between the two delivery channels.

MNP programming is incorporated into existing infant and young child nutrition (IYCN) work in Namutumba. Many partners are implementing IYCN activities in the district, focusing mainly on promotion of exclusive breastfeeding. The training for MNP distributors includes IYCN topics to ensure that MNP are part of the overall IYCN strategy in the district. Distributors provide messaging on the need to maintain continued breastfeeding, provide an adequate variety of foods, feed the recommended number of meals, and ensure adequate volume of food as they provide MNP to caregivers in the district. SPRING’s pilot launched in March 2016.

Intervention Design

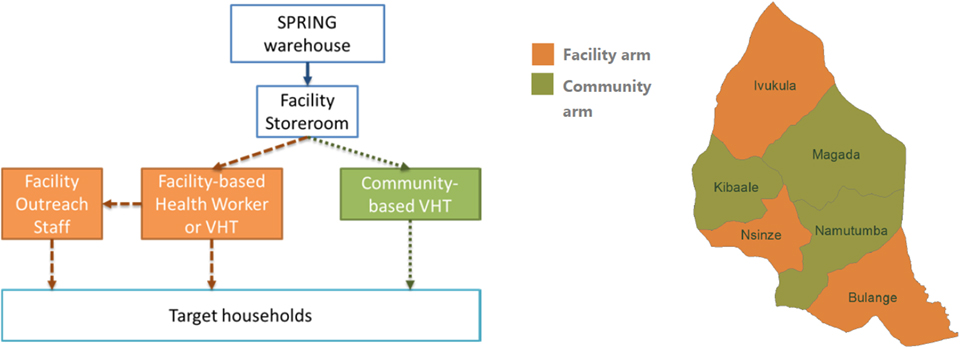

Caregivers in the facility arm (Kibaale, Magada, and Namutumba subcounties) receive MNP from health facilities, either during visits to the facilities or weekly outreach activities in the communities. MNP is available at the facility every day, but facilities make use of regularly scheduled clinics and visits that target eligible children, such as immunization days or well child visits. Additionally, facility staff and volunteers who conduct weekly outreach visits include MNP in the package of services provided. In the community arm (Bulange, Ivukula, and Nsinze), volunteer VHTs distribute the MNP directly to caregivers. VHT often distribute during visits to caregivers’ homes, but some prefer to organize groups of caregivers to receive the MNP all at once or wait for caregivers to seek them out at their home. SPRING encouraged VHTs to conduct the distribution in line with how they carry out their current VHT duties. Subcounties were randomly assigned to either facility or community distribution arms in a raffle process. See Figure 1 for details of this distribution method and the split of subcounties.

Figure 1: SPRING Intervention Design and Map of Namutumba District

SPRING estimates that there are about 25,000 eligible children in Namutumba district. At the time of this midline review, nearly 13,000 children were enrolled in the MNP program (meaning that they had received at least one packet of MNP). In each arm, the distributor is responsible for providing caretakers of eligible children (any child 6–23 months) with—

- one packet of MNP, containing 30 one-serving sachets for use over two months, and refills of the MNP packets until the child reaches two years of age

- communications materials including a sticker, adherence calendar, and enrollment card

- counseling on proper IYCF practices, possible side effects, and appropriate use of MNP: consumption regimen, correct mixing into food, and not sharing sachets (more details in the “Appropriate Use” section, below)

- additional counseling as needed to answer questions, address potential side effects, and support continued use of MNP.

Distributors submit monthly reports on activities, including number of packets received and delivered, number of eligible children enrolled in and exiting the program, and counseling provided. Distributors have monitoring forms for tracking stock movements, requesting additional stock, and maintaining lists of children enrolled in the program.

Health assistants in the community arm supervise VHTs, visiting on a regular basis to provide mentorship, assess storage conditions, and meet with caregivers. Subcounty nutrition coordination committees (SNCCs) members conduct supervision activities in the facility arm. The reporting and supervision systems mimic existing MOH processes (including adapting existing reporting forms) in order to include MNP in the normal workflow of health workers, health assistants, SNCC members, and VHTs.

Pilot Implementation in Namutumba District

Orientation, mobilization, and training activities for the MNP pilot took place across the district, creating a strong foundation for both distribution arms. Health workers and VHTs across both arms received sensitization around MNP before distribution began, with those responsible for distribution receiving a week-long (health workers in the facility arm) or two-day (VHTs in the community arm) training in MNP use, messages, communications materials, and monitoring tools. In addition, SPRING conducted sensitization of the district stakeholders at the subcounty level, and village sensitization in both arms of the distribution to create buy-in and demand for MNP, respectively. The national SBCC strategy informs ongoing communications activities within the district, which include radio jingles, advertisements, and talk shows aired regularly on the two main stations.

Distribution officially began at the end of February 2016, with most distributors receiving materials in the first weeks of March. SPRING supplied all health centers in the facility arm with MNP packets and communications materials. SPRING gave MNP and communications materials directly to VHTs in the community arm during initial meetings at the beginning of the pilot. For later distribution rounds, however, SPRING delivered materials to health facilities in the community arm, where VHTs would travel to pick up the supplies on an as needed basis. In both arms, supplies are kept in the facility stores with storekeepers responsible for maintaining stock records. Although in the first round MNP deliveries were based on a “push” system in which SPRING allocated the amount of stock for each distribution site based on census data, deliveries currently rely on a “pull” system in which SPRING delivers MNP based on requests received from distributors. All stock forms and processes mirror those used by the National Medical Stores for commodities within the MOH system.

Health assistants began their supervision visits in April. SPRING began supporting members of the SNCC in conducting supervision visits to health facilities and meet with caregivers in May. Early visits took place in conjunction with SPRING’s routine monitoring visits. Visits in both arms consisted of supervision of distributors to identify and address any weaknesses in their distribution activities. Additionally, supervisors conducted visits to nearby households to understand caregivers’ experiences with MNP and identify any additional areas of weakness to work on with the distributor.

Limitations of the Data in This Report

At the time we conducted the midline assessment, few caregivers had moved to their second packet of MNP. Because of this, our research assistants were not able to interview many caregivers about the experience of continued use. Although we can hypothesize about some of the issues that caregivers may face in continuing to give MNP to their children, our data do not provide concrete examples of this experience.

Additionally, this work reflects experiences and practices after only a short exposure to MNP. The novelty of MNP may begin to wear off, possibly leading to decreased discussion of the product in communities and decreased effort by busy distributors. Experience in Bangladesh suggests that sustained program success requires continued stakeholder involvement and maintenance of supply, monitoring, supervision, and communications activities (Afsana et al. 2014). This review cannot predict how the MNP intervention will continue to function, but it does provide some indication of areas to strengthen.

Midline Program Review as a Method for Program Improvement

SPRING carried out this midline qualitative review three months after the initial distribution (May 2016) to—

- identify barriers to distribution or use that need to be addressed in the pilot phase

- gather qualitative data with routine to provide context to the quantitative monitoring data and inform any course correction needed

- highlight important issues regarding distribution, acceptance, or use of MNP that SPRING should explore in during endline data collection.

Methodology

Design and Approach

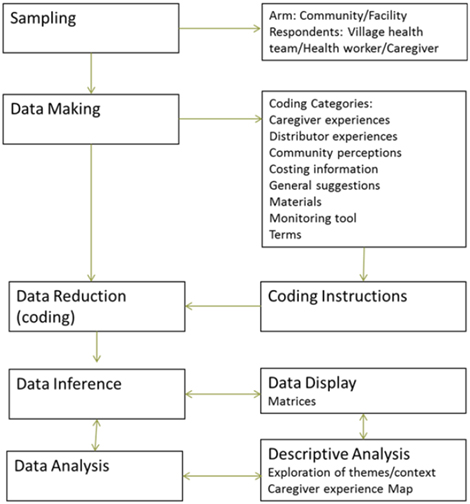

The midline review consisted of a series of interviews with health workers, VHTs, MNP users, and MNP non-users across the district (Figure 2). The interviews were focused on caregiver and distributor experiences with MNP, such as training, distribution, use, and feedback on SBCC and monitoring materials. The interviews were conducted using three semi-structured interview guides for VHTs/health workers, caregivers of non-user children, and caregivers of user children (see Annex 1).

Sampling

Based on demographic data available from Namutumba district officials and routine monitoring data collected by SPRING staff, all parishes in the district were classified as urban/peri-urban or rural4 and above or below average performance on routine monitoring indicators. To ensure a broad range of experiences, SPRING randomly selected two parishes from each of the four lists for each arm (facility or community) and respondent type (caregiver of a user, caregiver of a non-user, VHT, or health worker). This selection process is shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Parish Selection Process for Sampling

| Locations | User | Non-user | VHT | Health Worker | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Arm | Rural | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Quasi-urban | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Good monitoring data | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Poor monitoring data | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Facility Arm | Rural | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Quasi-urban | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Good monitoring data | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Poor monitoring data | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Working from a complete list of villages and health facilities in the district, SPRING staff randomly selected villages or health facilities for each of the chosen parishes. The last step of sampling took place during data collection—as teams arrived in the selected locations, they interviewed the first eligible participants they encountered. Health workers or facility-based VHTs at the facility who were present on the day of the interview and reported that they conducted MNP distribution or counseling were eligible for an interview. VHTs who were responsible for MNP distribution in the community arm and who were in the village (or nearby) on the day of the interview were included. Data collectors interviewed the first VHT they encountered in the village in the facility arm, since no VHTs are tasked with MNP distribution.

For user and non-user households, data collectors passed through the village going door to door, until they identified a household with a child between the ages of six and 23 months. For each village, data collectors conducted one interview with a caregiver of a child who used MNP and one interview with a caregiver whose child did not use MNP, with the order of the interviews based on those persons they first encountered.

Data Collection

Box 1: Local Terms for MNP

Some of the distributors refer to MNP as “powders” or “vitamin and mineral powders,” the name on the packet, but nearly all caregivers, and most VHTs, used other words, in one of the local languages, to refer to MNP. The most common terms illustrate a medical view of MNP, as well as recognition that they are specially formulated for children.

| Term | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Birungo or ebirungo | Ingredients |

| Buleezi or eyidahala | Medicine |

| Emere yo mwana | Child’s food |

| Ebiliisa, ekiriisa, kiliisa, ekilisa | Nutrients |

| Ebimeere bya’baana or Obumere bwa bana | Food for children |

| Ebirungo bya’baana | Ingredients for children |

| Obulezi | Medicine |

Research assistants participated in a three-day training led by SPRING staff that introduced the basics of MNP, SPRING’s programming in Namutumba, general qualitative methods, GPS and voice recorders used during the data collection, and the SPRING MNP midline tools. All data collectors had previous experience in qualitative data collection and transcription. The training culminated in a pre-test exercise in which groups of two conducted a full interview in the field, took field notes, and transcribed part of the interview for review by the SPRING team. Based on results from this pretest, SPRING staff reviewed the data collection tools, producing final versions for field.

All interviews with health workers were conducted in English, while the interviews with VHTs and caregivers took place in the respondents’ preferred language (Luganda, Lusoga, or Rusiki). Research assistants recorded all interviews and collected GPS coordinates from each interview location. Research assistants typed up transcripts of each interview in English, providing a translation and the original phrase for local terms used to describe MNP and any other concepts without a direct translation to English (Box 1).

Data Analysis

At the end of each day of data collection, research assistants debriefed with SPRING staff to highlight any emerging themes from the day’s interviews. Additionally, all teams met halfway through the data collection and again at the end to review emerging themes as a group and determine if the interview guides needed any modifications. Notes from these conversations fed into the development of the initial code book.

The research team met to discuss and agree on the included codes at the beginning of the coding process, and met again to discuss revisions after the first round of coding was complete (coding categories are listed in Figure 2). One team member took the lead in developing the code book and coding all transcripts, while two other team members reviewed the codes and coding throughout the process. Team members conducted the coding using Nvivo (version 10) and used Excel to develop a set of coding matrices to analyze experiences of the various respondent groups and types.

Figure 2: Data Process Map

The narrative below reflects themes and findings from the interviews, with quotes provided before the narrative for illustration. To maintain the anonymity of our respondents, quotes are identified only by respondent type (user, non-user, VHT, or health worker), distribution arm (facility or community), and when applicable, child age. Note that due to variation in the timing of initial distribution, MNP were available to respondents for two to three months prior to this activity, leading to some variation in experiences.

Ethical Approval

The midline review is part of the study protocol for SPRING’s MNP pilot in Namutumba district, approved by the College of Health Sciences’ Higher Degrees, Research, and Ethics Committee at Makerere University’s School of Public Health as the on-record Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the John Snow, Inc. (JSI) IRB of Boston, Massachusetts, USA. The Uganda National Council for Sciences and Technology provided final clearance to conduct the study.

Results

In total, SPRING conducted 64 interviews with health workers, VHTs, MNP users, and MNP non-users (16 interviews per respondent type). Analysis of the caregivers’ experiences with MNP identified factors that supported (facilitators) and that reduced or blocked (barriers) the behavioral objectives of the MNP intervention—namely, appropriate and continued use. Subsequently, we examine the factors affecting MNP distributors’ (VHTs and health workers) ability to support caregivers to carry out these behaviors.

Of the 32 caregivers interviewed, most were between the ages of 20 and 30, with only 7 older respondents (5 non-users) and one younger (user). Respondent households had an average of four children, but only one child eligible to receive MNP (between 6 and 23 months). Three of the caregivers with a child who did not use MNP reported previously using the product. The reasons they reported for ending their use included the following:

- The child (who was feeding himself) was not eating food with MNP added.

- The facility arm caregiver was waiting for a VHT to bring a refill, since the health facility was too far away.

- A community arm caregiver reported that she stopped using MNP when her child fell sick and lost his appetite.

Users who received packet of MNP in May (7 of 16 interviewed) had nearly full packets remaining (over 25 sachets on average). The rest of the users had received their packet in March, and all had fewer than ten sachets remaining. These correspond roughly with the amounts we would expect to see if caregivers are feeding MNP three to four times per week. Only two respondents reported receiving refills. All users reported giving MNP in the week prior to the interview, with nine reporting giving MNP the day of or day before the interview.

VHTs reported holding their position longer than health workers (an average of five and a half years compared to three). There was a difference in experience between arms, with the health workers (n = 8) and VHTs (n = 8) interviewed in the facility arm having nearly the same years of experience (five years) on average, while health workers in the community arm (n = 8) had less than two years of experience in their position and VHTs (n = 8) had nearly eight years of experience. It is important to note that our sample sizes are very small. These descriptions should be used only to understand the background of interview respondents and not as a description of distributors in Namutumba district.

Caregiver Experiences

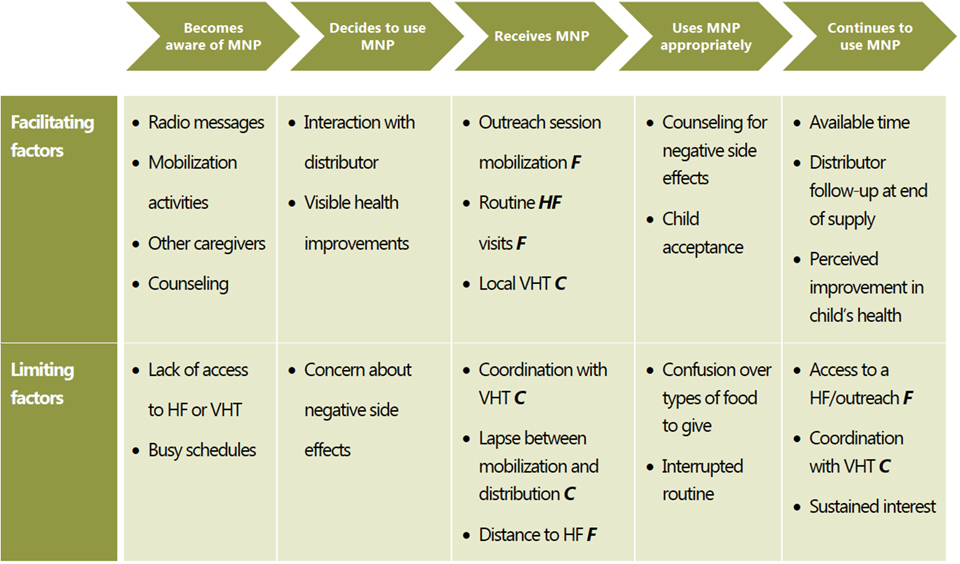

Based on synthesis of the findings of this review, SPRING developed a “caregiver experience pathway” to summarize the process respondents described during interviews. In this pathway, caregivers move from awareness of MNP to continued MNP use. Figure 3 provides a visual aid of potential facilitators and barriers at each step that help determine a caregiver’s ability to meet the pilot objectives of appropriate and continued use. Some caregivers were not able to proceed past one of these steps, and they stopped using MNP.

Figure 3: Caregiver Experience Pathway

*Factors specific to one distribution arm are labeled C (community) or F (facility).

We have used this pathway to organize discussion of the caregiver experience, drawing out the lessons and themes around each of these areas. The map also identifies areas where actions by MNP distributors (health workers or VHTs, depending on distribution arm) can influence a caregiver’s ability to use MNP appropriately and continuously. It is important to note, however, that the experience of each caregiver is different—some caregivers may become aware of MNP during their first counseling visit, suggesting that awareness of, deciding to use, and receiving MNP could occur simultaneously, rather than in a linear process. Other caregivers may in fact experience the linear process as they move from awareness to continued use. The map is meant as a descriptive aid, allowing us to organize caregivers’ experiences along the path to appropriate and continued use of MNP.

Awareness: Widespread and Based on Various Sources

Overall, the majority of caregivers (whether their children used MNP or not) were aware of MNP, demonstrating that communication efforts have been successful in spreading awareness of MNP.

I first saw them from my sister, she showed them to me. When I asked her what they are she told me they are “bilungo” (ingredients) for children…when the child eats them, she becomes heavy on weighing…one who has been weak becomes strong.

—Non-user in the community arm, with seven children, one child 6–23 months of age

Targeted caregivers reported first hearing of MNP from a variety of sources:

- Radio announcements

- VHTs mobilizing caregivers to access MNP or offering counseling

- Health workers mobilizing caregivers or during health facility visits for other purposes

- Other caregivers currently using MNP

Caregivers report that each of these sources provides information about benefits of MNP and sometimes provides directions for how to access and use the MNP. While caregivers living in peri-urban and urban settings hear about MNP from all of these sources, the majority of rural caregivers hear about MNP from a VHT or health worker. Otherwise, caregivers in rural and urban settings had very similar experiences hearing about MNP.

Although some non-users claimed they had not heard of MNP, further probing revealed that almost all had heard of MNP, but many had not received counseling, or were unaware of how MNP could benefit their child. The only caregiver who had never heard of MNP did not own a working radio.

Depending on how I am taught and the way I see other people’s children who use them, that gives me the energy to give [MNP] to my child...

—Non-user in the community arm, with two, children, one child 6–23 months of age

Caregivers currently using MNP have a particularly strong influence, as visibly improved health in children on MNP is a strong motivation for caregivers to use MNP. Even caregivers who did not give their children MNP frequently noted that they had seen other children grow stronger after using MNP, encouraging them to give MNP to their children.

Some caregivers had never heard of MNP before a counseling discussion with their health worker or VHT. While counseling is discussed further under “Appropriate Use,” it is important to note that awareness and counseling occur simultaneously for some caregivers. In these cases, distribution outreach or a health facility visit for other reasons results in gaining awareness of MNP and often simultaneously leads to engaging with and accessing MNP.

Decision Making: A Caregiver’s Task in Balancing Benefits and Concerns

Most caregivers who hear about MNP decide to give them to their children. Positive views of MNP in the community and support of other family members facilitate this decision. While concerns of negative side effects exist, no caregiver reported that the rumors affected their decision to give MNP.

After hearing about MNP, caregivers must decide whether they plan to access and use MNP. Caregivers usually follow one of three pathways: 1) they decide to access MNP on their own and seek it out, 2) they encounter MNP at a distribution point, or 3) they do not encounter MNP. (While caregivers could possibly encounter MNP but not use it, we did not interview any caregiver who had done that.) For each of these experiences, decision making occurs differently.

I listen to what is being said about [MNP] on the radio. For example, when they say that it has medicine for "Lwenyanja" (severe undernutrition)…I say to myself ‘If I give it, maybe, you never know, I may be able to prevent some diseases like undernutrition.’ That motivates me to go ahead and give my child these things...

—User in the facility arm, with two children, one child 6–23 months of age

For the caregivers who actively seek out MNP from a health facility or VHT, the decision to access MNP is active and self-motivated. These caregivers report that they are motivated by the healthy child shown on the MNP package and often discuss the perceived health benefits such as weight gain and improved physical appearance of skin and hair. They also report being motivated by the improved health and appearance of children taking MNP.

The first time I heard about them, I had gone for polio immunization at Namakoko primary school. They brought the VHT and taught us about [MNP]...

—User in the facility arm, with one child 6–23 months of age

The second category of caregivers were those who accessed MNP during an unplanned visit by a VHT, a distribution outreach, or a health facility visit for other purposes. These caregivers do not necessarily make an intentional decision to seek out MNP, and their decision to engage with MNP is influenced by direct contact with VHTs or health workers. This group reported that they, like caregivers who seek out MNP, were motivated by the perceived health benefits for children who use MNP, as well as a belief that it is important to follow the advice of their health care providers.

Interviewer: Why didn’t you go back to the health center to get [MNP]?

Caregiver: … [My child’s] condition was not attracting me to go and get them

Interviewer: Was he sick?

Caregiver: He was in good condition.

—Non-user in the facility arm with seven children, one 6–23 months old

Caregivers who do not encounter these distribution points or are not self-motivated to access MNP on their own remain non-users. Although most of these caregivers have heard of MNP, they are not motivated to seek them out. In some instances this is because communication channels did not effectively make them aware of the purpose or importance, like in quote above, where a mother of a healthy child says his condition is good and does not require MNP, or because they have not yet accessed distribution points. No respondents reported receiving MNP but then deciding not to use it.

Caregiver: I would still base [my decision to use MNP] on the condition of the children who

have been given [MNP].

Interviewer: So if [they are] in bad condition you also don’t give?

Caregiver: No, I don’t give. I will have lost the guts to give.

—Non-user in the facility arm, with three children, one child 6–23 months of age

When deciding to use MNP, caregivers often express a concern about negative side effects such as diarrhea, vomiting, and loss of appetite or refusal to eat. Both users and non-users voiced concern over possible side effects of MNP, although most users reported receiving counseling that specifically dealt with this issue. Some caregivers report that they initially resisted using MNP, but changed their minds after conversations with friends, family, or neighbors who are MNP users themselves. For more about the concerns caregivers have during the decision-making process and the role of their peers in allaying those concerns, see Box 2.

Despite expected wariness on the part of other household members, husbands and other family members do not have a strong role in the decision to access or use MNP. None of the caregivers reported negative responses from their husbands or identified a family member as a barrier to accessing or using MNP in their household. This may be a difficult topic for respondents to address in a short interview; additional data that can support or disprove this finding are needed.

Receiving MNP: Relying on Distributors to Take the First Step

Across both arms, caregivers showed a preference for MNP distribution methods that did not require them to go out of their way or adjust their schedule. For many non-users, distance from a health facility or lack of interaction with a VHT served as the main barrier to giving MNP to their child. Caregivers access MNP in either a community or health facility setting. In each arm, there are multiple ways for caregivers to access MNP, as below.

Facility arm:

- VHTs or health workers mobilize caregivers to attend distribution outreach events.

- Caregivers visit health facilities for routine services or due to illness, and health workers use the opportunity to enroll the child in the MNP program.

- Caregivers visit health facilities for the purpose of accessing MNP.

Community arm:

- VHTs visit caregivers’ home to distribute MNP.

- Caregivers visit a VHT who is distributing MNP from their home.

…They [the health worker] came around telling us that those children under two years should come and get ekilisa kya-baana [nutrients for children, referring to MNP]…When we received the news, we went very fast to the health center and we got them…

—User in the facility arm, with six children, one child 6–23 months of age

Box 2: Tackling Concerns, Misinformation, and Myths around MNP by Sharing Experiences

Some get discouragement from the neighbors and community friends. There is one who gave [it to] the child and the child got diarrhea...We heard them saying that they don’t give [it] because their neighbor gave [MNP to] the child and the child got diarrhea.

—Health worker in the community arm

Caregivers, health workers, and VHTs described community wariness of MNP stemming from worries about negative side effects and uncertainty around the motivations of SPRING and the government in bringing the MNP to Namutumba district. Few respondents mentioned that they were personally concerned with these issues, but nearly all described them as common worries of their neighbors and other community members.

If you don’t tell them that feces of their children will change color, they complain that their children defecates dark stool and for us whom they tell, we know there is no problem.

—Health worker in the facility arm

Some caregivers worry that MNP will cause negative side effects such as diarrhea, vomiting, and loss of appetite or refusal to eat. Distributors also report hearing similar comments when they speak with caregivers. The concern over diarrhea is particularly common and can be perpetuated in the community, as some children do experience diarrhea for the first few days they are given MNP. Diarrhea is generally mild and temporary, but caregivers’ perceptions of MNP are still influenced by hearing about this experience.

Many say that those things, Museveni has brought them to kill our children to reduce...the people and I will not give them…Many say [things] like that…

—Non-user in the community arm, with two children, one of MNP age

Health workers and VHTs report that when they started distributing MNP, caregivers expressed concern that the government had malicious intent in promoting MNP. Caregivers also reported that they heard MNP would affect fertility, kill their children, or was being used by the government to control population growth. Others heard that Europeans are using MNP to try to stop Ugandans from reproducing. These myths are perpetuated in the community and can cause caregivers to distrust MNP. Similar to discussions of side effects, while most respondents had heard of these worries, none reported that they believed or were personally concerned about the rumors.

They asked me…‘What about yours, do you give them [MNP]?’ Then I [say] ‘Yes, I give them. Come here and see when I am giving them,’ and some took time to come and see...So they see what I am doing, then they also do.

—VHT member in the community arm

My first client was a health worker…So she is the one who gives [other clients] clear information… [saying] ‘true, the child [has diarrhea], but not too much, and the child gets appetite and indeed my child is big and looks good.’ And indeed she gives [MNP to her child], and she was the first client. So she is the one who gives them information.

—Health worker in the facility arm

When caregivers are able to observe the improved health of other children taking MNP, their concerns about negative side effects or government intention are minimized. Caregivers’ trust and motivation to use MNP is heavily influenced by this peer modeling, especially when the caregiver is also a VHT or health worker.

VHTs and health workers who have children taking MNP are particularly well positioned to encourage caregivers to use MNP, as they are viewed as knowledgeable and having personal experience. Leveraging this influence while counseling on MNP could increase caregiver knowledge and trust in MNP use, and also provide peer role models that could be an effective asset to motivating caregivers and increasing uptake.

Unsurprisingly, easy access to a health facility, outreach activities in the community, and proximity to the VHT all serve to facilitate caregivers’ access to MNP. While caregivers could travel to a distributor to access MNP in either arm, most relied on health workers or VHTs to offer the MNP, either during routine facility visits (facility arm) or home visits (community arm).

We were here seated and a [VHT] came and asked, ‘Do you have a young child?’...She told us that they want mothers who have children at the hospital. So me, I went with many other women and they told us that ‘here is the children’s food they sent us, it works on children.’

—User in the facility arm, with six children, one child 6–23 months of age

Some caregivers who heard about MNP through mobilization activities that preceded the distribution expected VHTs or health workers to approach them when the MNP were available. If distributors do not approach these caregivers directly during a routine health facility visit or home visit by a VHT, the caregivers often do not obtain MNP. While most VHTs report conducting home visits to distribute MNP, health workers are limited to distributing MNP to those caregivers who attend the health facility or outreach events (including for non-MNP reasons), giving them little opportunity to provide MNP to caregivers who do not actively seek out MNP by visiting a facility or outreach event.

Access Differs Based on Delivery Channel

Most caregivers experience barriers to MNP access and these barriers differ depending on whether they are accessing MNP in a community or facility setting.

Caregiver: Since [the VHT] came when I wasn’t around, she told me to go and pick them from her place.

Interviewer: Okay, how many minutes does it take you to walk from your place to hers?

Caregiver: In 40 minutes I can be there.

—User in the community arm, with five children 6-23 months of age

Caregivers in the community arm have access to MNP through VHT distribution efforts. While many caregivers report that accessing MNP in this setting is easy due to proximity, coordinating to meet with VHTs at the caregiver or VHT’s home can be a barrier, especially for caregivers engaged in long work hours. In the cases where VHTs conduct distribution activities from their homes in the community arm, distance can become a barrier and coordination is again an important consideration.

Mothers are positively responding because at least we have not had any negative attitude and those who are failing to come it is because of their schedules…

—Health worker in the facility arm

In the facility arm, caregivers access MNP from health workers or facility-based VHTs at local health facilities. Although caregivers report that accessing MNP in this setting is generally easy, distance to the health facility, and the cost to get there for the few who reported using transportation other than walking, is a potential barrier. As is the case in the community arm, fitting these activities into an often-busy and long day is often a barrier to accessing MNP. In addition, some caregivers in the facility arm reported facing long lines or delays at the facilities when they attempted to collect MNP, a finding health worker interviews also identified (see “Workload” below), although none cited these delays as a barrier to their use of MNP. One nonuser reported that a health worker said her one-and-a-half-year-old child was “old” for MNP (non-user in the facility arm, with three children, two of MNP age). No other caregivers described this situation, nor did health workers report any confusion over eligibility ages, but this experience highlights the importance of regular training and supervision of health workers.

Appropriate Use: Quality Counseling Supports Proper Use of MNP

Overall, caregivers reported using MNP appropriately and understood how they were supposed to give MNP to their children. Counseling is an important part of MNP distribution and supports caregivers to give MNP appropriately. Children respond well to MNP, simplifying the process of giving MNP.

Once caregivers have received MNP, they must practice “appropriate use”—that is, understand the regimen for MNP dosing and give to their child based on those guidelines. VHTs and health workers counsel caregivers to give MNP based on four main messages. These messages are based on the formative research and national SBCC strategy, and appear across the communications materials:

- Give one sachet every other day (three to four times a week).

- Mix the MNP into soft, thick foods that are not hot.

- Do not share the sachet.

- Follow related IYCF behaviors, such as providing a balanced diet, continuing breastfeeding, and practicing good hygiene.

Caregivers typically report using MNP appropriately (more details on these practices in Box 3). Interviewers asked about the last time the caregiver gave MNP to the child, the usual schedule for giving MNP, and whether the sachet was shared, as well as asking the caregiver to describe the process they went through to prepare MNP and feed it to their child the most recent time it was given. This appropriate use of MNP is likely the result of caregivers receiving group or individual counseling from VHTs and health workers that is harmonized with the MNP communications materials in both the community and health facility setting, as well as the support other household and community members give for MNP use. Caregivers do not feel compelled to ask permission from their husbands before giving their child MNP but they often say that husbands have a supportive role in MNP use, typically by reminding caregivers to give the child MNP and purchasing the necessary foods.

Box 3: MNP Feeding Practices

Along with the three main guidelines for appropriate MNP use, health workers and VHTs also provide counseling on IYCF practices, with a focus on appropriate hygiene practices to prevent diarrhea. Overall, caregivers who gave MNP to their child had a good understanding of the recommendations.

Give one sachet every other day

Interviewer: Do you give on a daily basis?

Respondent: ...You give for one day and skip the other.

—User in the facility arm, with two children, one child 6–23 months of age

Caregivers currently using MNP typically report that they give MNP to their child three to four times per week, or every other day. Caregivers can experience interruptions in MNP use due to a change in routine such as moving to take care of a sick relative. Caregivers reported forgetting to bring MNP with them when they travel away from home.

Mix MNP into soft, thick foods that are not too hot

I cooked sauce, tomatoes and Mukene [a type of fish], I then cooked posho…I brought a plate after it had cooled, I put on the food, brought the sauce and then mashed until it was like porridge. After mashing, I brought the [MNP] and added to it...Already I had washed my hands, then I began feeding her…

—User in the facility arm, with one child 6–23 months of age

Caregivers mix MNP with foods such as posho (typically made from maize), millet, amaranth, and sweet potatoes. These foods are cooked and mashed to form a thick porridge and sauces or foods such as eggplant, tomatoes, Mukene fish, and groundnuts are often added. The preparation process includes cooking, mashing, and allowing the food to cool before the caregiver mixes in the entire sachet of MNP.

Caregivers do not note any issues with MNP changing the color of food. A few caregivers explained that adding the MNP to food that has cooled down and mixing well prevents color change.

I usually grow potatoes, cassava, rice, which I can give her to eat, but these additional [foods] I may fail to get.

—Non-user the community arm, with three children, one child 6–23 months of age

Interviews suggest that many households face barriers to accessing IYCF recommended foods. In these situations, caregivers are still able to use MNP, but are not able to obtain the variety that counseling suggests.

Do not share the sachet between multiple children

Interviewer: “Do you share these vitamins with other children?”

Respondent: “No, I give to only her...because when I give [to] others, ingredients become not enough.”

—User in the facility arm, with four children, one child 6–23 months of age

No caregivers reported sharing the MNP with multiple children. The finding was universal across all interviews.

Use appropriate hygiene practices

Of course you have to wash up clean, you can’t just come from the garden in those dirty clothes and just touch your child’s porridge. You need to first wash up and even change to clean clothes and then touch the porridge and give to the child.

—User in the facility arm, with two children, one child of MNP age

Many caregivers emphasize handwashing and cleanliness as a key component of food preparation. Health workers and VHTs emphasize using these proper hygiene practices as a way to prevent diarrhea.

Use of communication materials in general helped support the appropriate use of MNP (Box 4), although counseling appears to be an even more important factor. Caregivers’ similar understanding of and familiarity with messaging related to appropriate use across both arms suggest that counseling quality did not differ between the community and facility arms. Users and non-users report different experiences and access to counseling, and have differing levels of awareness of the three main messages.

[The counseling] was easy, because they told me that you wash your hands, and if the food is on fire, [cool] it down. It should not be too hot, and if you have a spoon or if your hands are not dirty, you mash that food, then add that vitamin, mix, and give it to the child to eat.

—User in the facility arm, with two children, one child 6–23 months of age

Users in both arms typically reported that they received counseling on MNP food preparation and practices and they understood the counseling. The counseling given to users focuses around how to prepare foods for mixing the MNP into, especially emphasizing the importance of temperature and hygiene practices. Users are able to describe MNP practices in detail and suggest they both understand and find counseling easy to follow.

For me what I am asking…if I have given them to my child, are there any bad things it can bring like okufukuka omubiiri (skin rash)?

—Non-user in the community arm, with seven children, one child 6-23 months of age

Non-users often do not receive counseling and in turn have many questions about MNP for the interviewers. For example, non-users asked the interviewers about how to access and use MNP, the benefits of MNP, and most commonly, if MNP could cause harmful side effects. Non-users who had received counseling in the past often report that the counseling was brief and did not provide much detail. Those caregivers who reported that the counseling they received was brief or not very detailed often failed to decide to use MNP.

Child Response: Acceptance Facilitates Appropriate Use

He doesn’t refuse it. Even when you are cooking, before you finish, he carries the packet to bring it so that you can add [it] for him. If the food takes long to get ready, then he wants you to give him the MNP and he eats them like that.

—User in the community arm, with one child 6-23 months of age

Of course, caregivers can only follow the recommended guidelines if the children accept and consume food mixed with the MNP. Children often have a positive response to the taste of MNP, and older children are typically aware that it is being added to their food. Some caregivers report that their child even helps them to remember to use MNP. Overall, taste is not a barrier for caregivers using MNP.

Box 4: Feedback on Communications Materials

Caregivers who access MNP are provided with four materials that support appropriate MNP use. While health workers and VHTs voiced concern that nonliterate caregivers had trouble with the adherence calendar, most caregivers did not report difficulties understanding or using the communications materials.

Adherence Calendar

This calendar helps to know that today I have given [it]; tomorrow I do not have to give [it to] her, then I have to give [it] the other day...It helps me, it reminds me, because even when I have forgotten to give [it to] her...every time I enter into the house I look at it, [and] I see today is for giving her the ingredients…

—User in the facility arm, with four children, one child 6-23 months of age

All caregivers are provided with a specially designed calendar at their first distribution to help them adhere to the MNP schedule. Caregivers should mark the calendar on days they have given them (three to four times per week). Caregivers in the community arm typically use the calendar as intended, but caregivers in the facility arm often do not use it, saying that they are able to remember the MNP schedule.

Health workers and VHTs in the community arm commented that the adherence calendar can be difficult to use for caregivers who are illiterate.

Enrollment Card

About the card, I don’t know because the person who taught us didn’t tell us, so I don’t understand.

—User in the facility arm, with six children, one child 6-23 months of age

All caregivers are provided with an enrollment card that details information about the child receiving MNP at the first distribution. The card is updated at every distribution and includes the refill date. Caregivers in the facility arm were often not sure of the purpose of the enrollment card. Some were not counseled on the card, while others were told only that they needed to keep it. In the community arm, almost one-half of the caregivers did not receive the enrollment card. In these cases, VHTs often kept the card instead of leaving it with the caregiver. Caregivers who did receive the card understood its purpose in the refill process.

Health workers and VHTs did not report that caregivers had any difficulties using the enrollment card.

Sticker

It directs me...You see [that] here, you are washing your hands, here you are mixing, here you are opening [MNP] to add to the food, here mixing, and here feeding the child…

—User in the community arm, with five children, one child 6-24 months of age

All caregivers are provided with a small sticker at their first distribution that serves as a reminder to give MNP, as well as a sign to others that the household uses MNP. The sticker uses visuals to remind caregivers of the proper way to prepare and give MNP. Caregivers easily understood the purpose of the sticker and used it to remind them of MNP practices they had forgotten.

Health workers and VHTs did not report that caregivers had any difficulty using the sticker.

MNP Packet

The purpose of the MNP packet is to store the MNP sachets and allow caregivers to keep empty sachets. Caregivers understand this purpose and use the package to keep MNP sachets all in one place and safe.

We tried opening [the packets]: some powders were 30 others were 28, others were even 22…

—Health worker in the facility arm

Distributors did report that the packets often did not contain 30 sachets, due to packaging error. Aside from confusing caregivers, this also complicates the timing of refills, since caregivers may complete the packet before a planned refill or might not be ready for a refill at the expected time.

Continued Use: A Potential Difficulty

Giving MNP appropriately for two months is not enough to cause a decrease in anemia. The effectiveness of MNP relies on continued use of the product from ages 6 to 23 months. While the interviews took place three months after MNP distribution began in the district, distribution delays in some areas and missed doses meant that few children had completed their first packet.

Returnees are few, but those coming for the first time are many.

—Health worker in the facility arm

Only a few caregivers reported picking up their refills and distributors said only a few caregivers had come back for refills. Therefore, given the early stage of the pilot, there is limited experience on continued use.

I have seen my child’s skin improve, and I have not seen him fall sick. Ever since I started giving him those things, I have not seen any problem.

—User in the facility arm, with six children, one child 6–23 months of age

First of all, when my child eats [MNP] she gets good appetite. Secondly, for me, I see when I give them to her she grows well. She does not fall sick easily; that encourages me to give her those things.

—User in the facility arm, with one child 6–23 months of age

Caregivers generally reported they are motivated to continue to provide MNP to their child because of perceived improvements in health. Whether this factor remains a key driver of continued use will require a longer duration of intervention. Once a child finishes the first packet of MNP, the caregiver can actively seek out an MNP refill or wait for an MNP distributor to reach out and provide the refill. In the facility arm, any refill requires going to a health facility or attending an outreach event for a non-MNP reason, as there are no options for house visits.

Among caregivers that had completed their first packet, most expressed a preference for accessing refills from VHTs, although coordination is essential. To get a refill, caregivers need to know when and where VHTs are distributing MNP, and the distribution times cannot conflict with caregivers’ schedules. Caregivers in the facility arm who did not experience distance as a barrier suggest that accessing refills from the health facility is easy, as the location and times are reliable.

…Those who are returning are not returning on time and are taking it as giving burdens.”

—Health worker in the facility arm

Caregivers who were due for their next refill but had not yet received it often said they had not found the time to pick up the refill or that they were waiting for the VHT to return to their home with a refill (community arm). Caregivers also reported that traveling out of the village made it more difficult to access a VHT for refills on the suggested refill schedule. Interviews with non- and former users suggest that users who face difficulties in accessing refills could face long delays in restarting MNP use or may stop using MNP all together.

Despite the difficulties in refilling MNP, caregivers and distributors agreed that reminders or check-ins from a VHT or health worker at the end of a caregiver’s MNP supply could facilitate the refill process. Health workers pointed out that at the facilities they have little opportunity to interact with caregivers who do not return for their refill.

Side Effects: A Barrier Counseling Can Solve

At the start he got diarrhea but I told the health worker who gave us these things and he said, ‘He has to get diarrhea first but he will be ok’…I continued giving and giving and the diarrhea stopped.

—User in the facility arm, with six children, one of MNP age

Some of them say that am giving these MNP to my child but the stool has turned a little bit so you just encourage them that [as] you continue giving it will change slowly and become to normal.

—Health worker in the community arm

Although children may experience diarrhea initially when they start taking MNP, long-lasting negative side effects are not common. MNP distributors are trained to warn users of the possibility of diarrhea and they encourage caregivers to take children to health care providers if the diarrhea persists for longer than a few days. Access to counseling, especially with an emphasis on WASH practices, prevents diarrhea from becoming a barrier to appropriate use, by ensuring caregivers are able to differentiate between acute diarrhea that is common at the start of MNP use and chronic diarrhea that requires medical attention. The resulting improved physical health of their child motivates caregivers to appropriately use MNP.

Other reported side effects included swollen stomach, passing gas, vomiting, and skin rashes. Most of the reported side effects had ceased by the time of the interview. Only one child continued to show a skin rash that the caregiver said began when MNP was given, and she was encouraged to take the child to visit a health facility. No caregivers reported that they had stopped giving MNP because of side effects.

Distributor Experiences

Even the malnutrition itself has reduced a bit, because those days it was really rampant, but [in] a month you can get [about] three children, those days you would get like 10 in a month.

—Health worker in the community arm

We used to send cases of loss of blood to Namutumba all the time. But now [we do not].

—Health worker in the facility arm

The ability of caregivers to proceed successfully from awareness about MNP to continued use requires distributors (whether they are health workers or VHTs) to provide a reliable MNP supply and quality counseling to caregivers. Distributors identified training and workload as the two biggest factors affecting the caregivers’ experiences with MNP, especially accessing MNP and counseling.

Initial Training Is Helpful When Complemented by Refresher Trainings

Most distributors reported receiving formal training, and many who had not taken part in initial trainings were trained informally by other distributors. While the training program was well-regarded, many distributors voiced a desire for more continued training to allow them to continue addressing issues that arise during distribution.

It was comprehensive training because we looked at so many areas; one of them was type of food groups, what an MNP is…We even did food demonstrations like combining all the types of fruits…We also looked at logistics like MNP register…We also handled minor challenges, like when you’re giving MNP sometimes the feces of the baby tend to be loose.

—Health worker in the community arm

The training was good but...there are things you may want to be reminding us.

—VHT in the facility arm

Across both arms, at least one health worker in each facility (and some facility-based VHTs in the facility arm) received formal MNP training. The formal training lasts five days and includes information about MNP purpose, eligibility and use, distribution, food preparation, and hygiene, as well as proper IYCF behaviors. Two VHTs per village in the community arm participate in a formal two-day training, while community-based VHTs in the facility arm receive informal training (from their facility-based peers or supervisors) or no training at all. Training for VHTs focuses heavily on MNP eligibility and use, hygiene practices, and proper IYCF behaviors.

Recently, we just had what they call [a] review meeting...Even the questions that we used to get from [people in] the village, these people managed to sort them out so we left knowing what to respond.

—VHT in the community arm

Although distributors feel the training prepares them well for their work with MNP, continued training allows them to address any issues that come up during distribution that they need support in addressing. Since not all health workers and VHTs in the district attended the formal training, some distributors reported gaining their knowledge around MNP through informal on-the-job training by those who had.

Workload Has Increased for Health Workers in the Facility Arm

While VHTs did not report an increase in workload, health workers, especially those in the facility arm, reported that their workload had increased as a result of the MNP program. It is unclear the effect this increased workload has the program, but many caregivers in the facility arm do report delays in receiving MNP at the facility.

Now we use much time…[for] health education we were using like 45 minutes in a group but this time we are using an hour because one [person asks]a question and another [person] also [has] a question, so we are using much time…I have become a bit busy and active.

—Health worker in the facility arm

[My routine] has somehow changed because...of work overload. You find like in health center there are few staffs, but now those patients have been almost from morning waiting for MNP but there are only two staffs.

—Health worker in the facility arm

Health workers in the community arm did not report that counseling caregivers on MNP or supporting VHTs to distribute MNP had increased their workload. In contrast, health workers in the facility arm saw an impact on their work schedules, reporting that they often worked longer days or had to decrease the amount of time spent on other activities to make time for MNP distribution. These health workers report that adding MNP distribution and counseling to the services they provide increases their workload and can be challenging to manage in addition to their other responsibilities. Caregivers also report they travel to health facilities only to face long wait times and sometimes facility staff turn them away when staff are unable to handle the number of clients. While it is possible that additional factors, unrelated to MNP distribution, feed into these long waits, both health workers and caregivers reported these waits as a factor that complicates caregiver access to MNP.

What I can say is walking in this village, this village is very big...If they have called me to the subcounty as you see, there is a distance.

—VHT in the community arm

VHTs in the facility arm did not report an increase in workload despite some added responsibilities for counseling community members who come to them with questions. For VHTs in the community arm, counseling and distribution of MNP sometimes require a significant amount of travel, especially when VHTs are required to walk to each caregiver’s home or travel to health facilities to collect their stock of MNP. Availability of transportation is important in managing this added responsibility.

Supply Chain Contributes to Facility Staff Workload in Both Delivery Arms

Neither health workers nor VHTs reported any serious problems with the SPRING-led distribution process, and they reported few difficulties in moving MNP from storerooms to caregivers, namely those difficulties related to supplying caregivers with refills. Challenges related to supply came from its impact on workload.

Those people will come out from the village community, [saying] that they don’t have the MNP...so that means almost all the time you are...at the stores.

—Health worker in the community arm

In smaller facilities, the main health worker is also the storekeeper, but in larger facilities, other staff have to go through the storekeeper to access materials before outreaches or distribution. Some departments and clinics keep a supply of MNP on hand, sending requisitions to the store only when their own supplies get low. In the community arm, nearly all health workers supporting distribution to VHTs have found that they have to explain monitoring tools and requisition forms. Some storekeepers schedule specific days for the VHTs to come pick up materials, since the process can be time-consuming.

Supervision Provides an Opportunity for Addressing Weaknesses

Health workers did not report receiving supervision visits from non-SPRING personnel, and VHTs did not report any supervision. Given that supervision began the month before (by health assistants in the community arm) or same month (by SNCC members in the facility arm) as the midline data collection, it is not surprising that few distributors had participated in supervision activities yet.

It’s good to supervise because once they supervise you, you do what? You learn the good things you are doing and your weak areas.

—Health worker in the community arm

The primary type of supervision health workers reported receiving were visits by SPRING staff for data collection, which were reportedly beneficial for mentoring purposes. Although data collection was not originally planned as a supervisory activity, SPRING staff have used these visits to provide feedback to distributors on their progress. Health workers found these meetings helpful, especially for better understanding how to use the monitoring and data collection forms (Box 5), although these meetings also addressed questions around the product itself and the counseling activities.

Box 5: Feedback on Monitoring Tools

Health workers and VHTs receive monitoring tools from SPRING to support MNP distribution. The national

MN-TWG developed the tools, based on existing MOH forms. While the tools are separate from similar non-

MNP monitoring tools for the purposes of the pilot, they are designed to mimic the standardized tools that

would be used in a national program.

- The register is used to record the child’s information and follow-up date or refill date. It is used by health workers in the facility arm and VHTs in the community arm. Some health workers in the facility arm say that the client number is confusing and they are unsure of how to fill in register information for refills. VHTs said that while the tool was confusing at first, they now feel more comfortable with it.

- The log book tracks MNP distributed to caregivers. It is used by health workers in the facility arm, who do not mention any problems with it.

- The requisition book allows distributors to request more MNP from the store (VHTs) or SPRING (health workers). It is used by health workers in the facility arm. In the community arm, VHTs give their requisition forms to facility store keepers.

- The dispensing log tracks MNP dispensed to health workers and VHTs from the store. It is used by storekeepers in both arms. Health workers in the community arm do not report using it very often.

- The stock card tracks the MNP stock in store and is used by storekeepers in both arms, as well as VHTs in the community arm.

Discussion

This midline review shows that implementation of the MNP pilot in Namutumba district is going well. Communities are aware of MNP and have generally positive feedback and experiences. Caregivers know how to use MNP appropriately and encourage members of their community to use MNP also. However, there are reports of negative side effects and receiving refills prove to be a barrier for continued use. SPRING will need to address both in the remainder of the pilot. Finally, health facility staff report noticeable changes in their workload that will complicate efforts to continue providing quality counseling.

Successes of the Distribution So Far

- Overall community acceptance is high. Despite concerns over possible side effects and reports of rumors, nearly all caregivers had positive reactions to using MNP or were interested in learning more and using them for their children in the future.

- Caregivers know how to use MNP appropriately. As a result of the communication materials and quality counseling by well-trained distributors, caregivers report appropriate use and understand of how to give MNP.

- Distributors and caregivers perceive MNP users as healthier children. Nearly all respondents were motivated to provide MNP to improve their child’s health. These perceptions have helped to combat worries about side effects and contribute to widespread acceptance.

- Caregivers are acting as models for their communities, especially in urban areas. As caregivers show positive experiences using MNP, they act as informal MNP ambassadors to their neighbors, and distributors have an easier time in convincing caregivers to give MNP to their children. Rural users generally hear of MNP through formal channels, but in more urban communities, other users are important influencers.

Challenges to Implementation Identified in This Review

- Caregivers are reporting negative side effects. Caregivers reported hearing of side effects, as well as experiencing them in their use of MNP. Counseling seems to overcome these worries, but it could be a factor in some caregivers deciding not to provide MNP. Additionally, this finding highlights the importance of continuing to monitor reported side effects. Worries persist despite the fact that those who are already giving MNP report minor, if any, side effects and none report stopping MNP due to side effects.

- Access to MNP is easier in the community arm than the facility arm. Between reports on far distances to reach facilities and long waits once caregivers arrive, caregivers and distributors in both arms agreed that community-based distribution provided caregivers with easier access to MNP. However, receiving MNP in both arms seems to rely heavily on caregivers being proactive, which is a risk to continued use.

- MNP distribution increases the workload of health facility staff. MNP distribution, and the counseling that goes with it, adds a significant burden to already busy facility staff. Time pressure means that distributors might not have the time they need to provide quality counseling necessary for appropriate and continued MNP use. If they are able to find the time, it may come at the expense of other important facility activities.

Findings from This Midline Review Can Improve SPRING’s Pilot Implementation in Namutumba District

SPRING can make changes to its distribution in the time that remains of this pilot. These efforts should focus on converting non-users to users, preventing dropouts, increasing continued use, and strengthening supervision to distributors though the following approaches:

- Increase support for regular and continued MNP distribution through existing health facility outreach activities to expand access to MNP in the facility arm

- Provide continued training for distributors, that includes refreshers on the use of

monitoring tools and increased focus on the issue of refills - Expand current communications activities targeting caregivers to include a focus on accessing refills

- Target men and other community members as MNP enablers and potential motivators for continued MNP use in the household

- Provide VHTs with guidance on how to reach out to households more effectively

- Monitor and build on existing supervision activities

- Continue to address negative perceptions and side effects

MOH Can Use These Findings to Design a Scaled-up Program

This review has highlighted details about MNP distribution in the Ugandan context, from evidence gained during the MNP pilot in Namutumba district, that may be relevant to MNP scale-up in Uganda. These results are based on information from the early stages of the intervention and thus some of these findings may be modified as more data is collected. Deliberations on plans to roll out MNP more broadly may benefit from considering the following:

- Many eventual distributors of MNP will not be part of initial trainings, due to turn over or increased workload of trained distributors. Continuous training opportunities should also include a focus on providing mentorship and informal training to colleagues.

- VHTs are important for expanding MNP access, encouraging continued use, and providing targeted counseling. In the facility arm, caregivers, health workers, and VHTs agreed that VHTs need to play a greater role than they currently do.

- Some health workers in the facility arm are overwhelmed by the increased demands on their time due to MNP counseling and distribution. Sustainable MNP delivery relies on a plan that will not overburden distributors, one that can decrease access to the product or affect the quality of counseling caregivers receive. The MN-TWG should discuss how the program can be streamlined, for instance, by removing forms or process that do not seem to add value.

Areas for Further Study

This review covers a broad spectrum of themes and experiences in implementing an MNP intervention in the early stages of a pilot in Uganda. SPRING will address some of these issues in upcoming work, but there is also a need for other researchers to look into these areas: