The Case for Systems Thinking

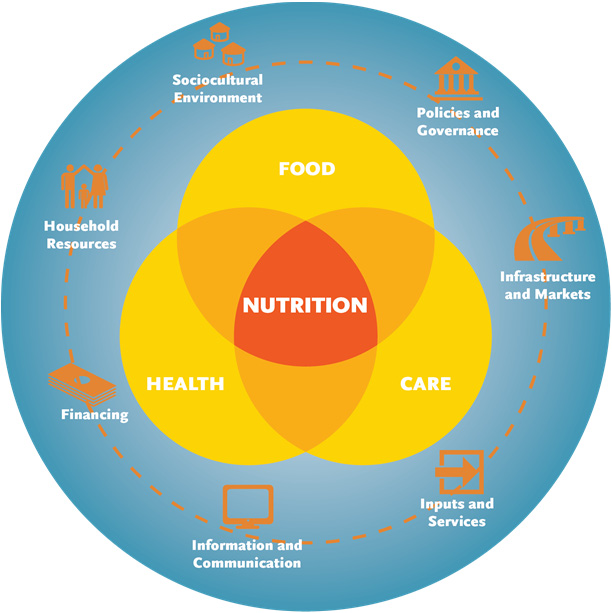

Figure 1. The SPRING Framework for Applying Systems Thinking to Nutrition

Today, the world faces a double burden of malnutrition, with almost three billion people suffering from either undernutrition or overweight (FAO 2013). No country is untouched by this crisis. Hunger and inadequate nutrition contribute to high rates of maternal, infant, and child anemia, morbidity, and mortality; impaired cognitive function and reduced future productivity; and the development of obesity and nutrition-related chronic conditions such as diabetes. The causes of this crisis are numerous.

In 2014, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) released its Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy (2014–2025), which recognizes the “multi- factorial causation” of malnutrition (USAID 2014a), and Local Systems: A Framework for Supporting Sustained Development (USAID 2014b), which suggests that systems thinking could benefit multi-sectoral approaches by strengthening program1 design, implementation, and measurement; increasing impact; and fostering sustainability. Enthusiasm for systems thinking is growing, but scant guidance exists on how to apply a systems thinking approach.

The Systems Thinking Assessment Tool

In 2015, USAID’s multi-sectoral nutrition project, Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING), developed a framework for applying systems thinking to improve nutrition (see figure 1 and panel 1) (SPRING 2015). The framework includes seven cross-cutting factors: (1) policies and governance, (2) infrastructure and markets, (3) inputs and services, (4) information and communication, (5) financing, (6) household resources, and (7) sociocultural environment. Each can influence, interact with, and impact the others; and each can hinder—or foster—improvements in nutritional outcomes.

With this framework and the accompanying thought paper (2015), SPRING made the case for policymakers, program planners, and program managers to consider these factors and how they positively and negatively contribute to desired outcomes; recognize interrelationships between them; anticipate the potential for negative consequences; and take advantage of synergies among existing systems, programs, and structures. It is important to emphasize that we do not expect that everyone will do everything at the same time.

Panel 1: The SPRING Framework for Applying Systems Thinking to Nutrition-Related Actions

In 2015, SPRING developed a simple framework for applying systems thinking to nutrition-related actions (figure 1), built off the work in USAID’s paper on local systems (2014b), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) framework of the causes of undernutrition (UNICEF 1990, 2013), and the World Health Organization’s building blocks for health systems (WHO 2010). This framework illustrates the interrelationships among the seven crosscutting factors described below.

1. Policies and Governance

Policies affect food, care, health, and the environment—although their level of impact varies according to adherence and enforcement. For example, maternity-leave policies and legislation can have an impact on breastfeeding practices in countries where the majority of women have formal employment. SPRING’s Pathways to Better Nutrition (PBN) case studies demonstrate that clear, long-term, multistakeholder policies are critical to increasing commitments for improved nutrition (Pomeroy-Stevens et al. 2016a, 2016b). Good governance, according to the former United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan, “is perhaps the single most important factor in eradicating poverty and promoting development” (United Nations 1998). The World Health Organization’s nutrition governance score, used to assess a country’s readiness to accelerate actions for improving nutrition, includes 10 elements essential for the successful development and implementation of national nutrition policies and strategies.2 Collaboration and coordination, in particular, has been widely emphasized because it affects the implementation of multi-sectoral nutrition plans at all levels and across departmental and sectoral boundaries (Levinson, Balarajan, and Marini 2013). SPRING’s PBN case studies also reveal that the prioritization of nutrition, another element of good governance, determines the amount of funding, time, and effort it will receive (Pomeroy-Stevens et al. 2016a, 2016b).

2. Infrastructure and Markets

Infrastructure, including roads and physical structures like health facilities, are critical to good nutrition: to educate and provide health and nutrition services and to store, distribute, and sell agricultural, food, sanitation, and hygiene products. The market is also essential in terms of the delivery, sale, purchase, and ultimately consumption of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) and health products. Markets can enhance, enable, or prevent improvements in nutritional status. For example, building a road to a market or trading post may allow a community to engage in value chains that impact incomes and access to healthy, diverse foods. And improving a market’s sanitation facilities can reduce the spread of food and waterborne pathogens.

3. Inputs and Services

A systems approach takes into consideration the nutrition related inputs, products, and supplies necessary for food production, storage, preparation, and distribution of nutrition services, ranging from seeds, fertilizers, silos, and food-processing equipment to preventive and curative medicines, medical devices, and technology. However, these inputs are of little use absent the human resources and services to provide, promote, and distribute them. This includes teachers, health care providers, extension and advisory workers, and even salespeople and distributors. Despite the global consensus on essential actions for addressing malnutrition, the workforce promoting them is often insufficient in number, underqualified, and unsupported. A systems approach calls for the better integration of nutrition into a wide range of broadly defined services.

4. Information and Communication

Information regarding the availability of food; the cost of agricultural inputs; the nutritional status of vulnerable people; the implementation of actions by enterprise owners, health service providers, farmers, households, and individuals; and the existence of policies and protocols is of little use without effective communication. Information communicated through government decrees, mass media, community mobilization efforts, and interpersonal interactions affects food security, care practices, and the health environment. For example, national-level changes to policies, financing, information, and monitoring systems are ineffective unless effectively conveyed at the community and household levels. Similarly, a failure to impart information about the cost of agricultural inputs can influence the types of food grown, stored, and purchased.

5. Financing

Adequate and effective financing is crucial to the development and implementation of nutrition policies as well as the strengthening of governance, infrastructure, markets, inputs, services, information, and communication. A lack of financing is among the most significant barriers to reducing undernutrition. The USAID Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy states: “political will for nutrition must be reflected through financial support” (USAID 2014a). Similarly, the 2016 Global Nutrition Report asserts: “commitment without funding represents unfulfilled good intentions” (IFPRI 2016). Because of the multi-sectoral nature of nutrition, activities related to it are often embedded in other sectors or funded through larger, integrated budget lines. This presents challenges to nutrition-related budgeting, allocations, and spending and makes it difficult to advocate or track funding for nutrition. Only a broad systems approach allows for the effective allocation and use of financing to holistically improve nutritional outcomes.

6. Household Resources

Household resources include human resources—knowledge, skills, agency, and self-confidence—and financial resources and assets, including technology. Access to and equitable intra-household distribution of resources drive their use and how people access services. Household resources also affect the understanding and adoption of optimal care practices as well as nutritional status. For example, access to an education and an income enables a woman to make well-informed decisions regarding her own health and nutrition as well as that of her children. Systems thinking links varied efforts to improve household resources and maximizes the use of resources for education, food, health, WASH, and other nutritional needs.

Socialcultural Environment

The sociocultural environment, including gender roles, relationships, cultural values, customs, and norms, influence the perceptions of and access to resources and services, as well as nutrition-related behaviors and decisions around production, purchasing, preparing, consuming, storing, and disposing. It also mediates interactions with the other six factors. For example, the belief that sugar water should be given to children at birth to whet their appetites, or that exclusively breastfed children need water when the weather is hot, hinders the adoption of evidence-based breastfeeding practices.

A systems approach does, however, mean that programmers and policymakers are intentional about what they will and will not do – and when they might seek partnerships with others in order to fill gaps. Nonetheless, questions remained as to whether such an approach was feasible or realistic for programming at the national and sub-national level.

To determine how well the SPRING systems framework maps to “real world” nutrition programs, we conducted a series of interviews with SPRING home office staff and field office staff, as well as country counterparts and program beneficiaries in Ghana and the Kyrgyz Republic, using a semi-structured interview guide (SPRING 2018a and b). Our findings indicated that the framework maps well to our programs in these two countries, and that it could shed light on the overlap between systems thinking, multi-sectoral approaches, theories of behavior change, and principles of good program design. We concluded that it would be useful in the future for assessing, designing, implementing, monitoring, and evaluating inter- and multi-sectoral nutrition programs.

Based on these findings, it was clear that there would be value in an assessment tool that is more widely useful and broadly applicable for other programs. Using the original assessment questionnaire as a starting point, we updated the tool for use at various stages of program design and implementation. After several rounds of review by SPRING’s multi-sectoral nutrition program experts working at headquarters and in field offices, we finalized this Systems Thinking Assessment Tool to help a wide range of actors, including government representatives, funding partners, and implementing agencies to—

- deepen understanding of the broader landscape of nutrition, including multiple stand-alone initiatives

- encourage collective ownership of efforts to improve nutrition

- raise awareness across sectors and levels of the many factors that affect nutritional outcomes

- strengthen design and planning processes by identifying the factors—across sectors—that should be prioritized and the interactions and the consequences that should be considered

- monitor the unintended the consequences of program-related actions and determine if additional steps are necessary to coordinate, collaborate, or address one or more factors in the framework

- provide a holistic view of a program’s achievements by identifying what contributed to and what hindered results.

How to Conduct a Systems Assessment

An assessment team, composed of government, funding, and implementing agency representatives, as well as beneficiaries, should agree on the leadership, methods, and timing of the assessment. The assessment will need to be led by one or two individuals—staff members or consultants of the government, funding, or implementing agency. The assessment can be conducted prior to program design, during strategic planning or work planning, and/or periodically thereafter, using one or both of the following methods:

- group discussions that bring together stakeholders from multiple levels (national, regional, district, and community) or separate discussions at each level

- key informant interviews at multiple levels.

The assessment team will need at least a day and a half for group discussions to foster full participation, obtain breadth and depth in responses, and agree on factor-specific scores. This could be organized to coincide with an already-planned meeting, such as a Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement partner meeting, a nutrition cluster meeting, a multi-sectoral meeting, or a program planning or review meeting. In any case, a skilled facilitator should lead the discussion and at least one person should take notes. Both the facilitator and the notetaker should be familiar with the tool and with nutrition-related systems thinking.

Using the tool as a guide for individual interviews can require two or more weeks because of the time needed to schedule and conduct multiple interviews with people knowledgeable about each factor in the framework as well as various aspects of the design, planning, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of the program. A skilled interviewer should conduct the interviews, and they should either be audio- or video-taped or recorded by someone taking detailed notes. Both the interviewer and the notetaker should be very familiar with the tool and with nutrition-related systems thinking.

Regardless of the method of data collection, a wide range of stakeholders, including program staff, funders, and beneficiaries from multiple levels and sectors, should be included in the process. Setting the tone for constructive, collegiate discussions is also important. This can be accomplished by explaining how participants’ input will be used and scores developed.

Based on the responses to each question, points should be assigned: “0” indicating that nothing was done; “1” indicating that something was done, but not much; and “2” indicating that a significant amount was done. The assessment team may choose to use an alternate scoring system. Depending on the purpose of the assessment, the team lead(s) should assign points or discuss and agree upon the points to be allocated with stakeholders. This type of process can help engage stakeholders in the conversation. Whatever scoring system and process is used, it should be consistent across locations, programs, teams, and/or time points so that comparisons can be made, if desired. Once all questions in a given section have been assigned points, the assessment lead(s) should calculate the total, the maximum number of points possible, the percentage of points assigned, and summary comments.

How to Use the Findings

Assessment findings are intended to guide discussions, establish collaborations, facilitate learning, assign priorities, define gaps, and identify needed adaptations. In this way, they aid adaptive management as well as collaboration, learning, and adaptation (CLA).3 But this can happen only if assessment teams present, share, and discuss findings, and stakeholders identify and take follow-up actions. Options for presenting the findings include—

- a radar chart presenting scores calculated for each factor (see figure 2)

- a graphic presentation of summarized conclusions related to each factor (see figure 3)

- a table of key findings (see table 1).

In group settings, stakeholders often share information and discuss issues as part of the process of answering questions and agreeing on scores, but if interviews are held with individuals separately, a meeting to share and discuss the findings as a group is essential. Meeting organizers can divide participants into small groups, with each discussing one of the factors, particularly what is needed to design, plan, and implement nutrition-related activities with a systems lens. After the findings are presented and discussed, groups may then agree on the score for each section.

Lastly, when using findings, it is important to encourage stakeholders to articulate concrete next steps. The findings could, for example, reveal a factor that is not being addressed, suggesting a need to shift resources, add or redesign interventions, or establish new partnerships.

The Systems Thinking Assessment Tool

The systems thinking assessment tool (STAT) is a series of questions related to each of the seven factors described above. These questions can help determine the extent to which systems thinking has been applied (see panel 1). Although the interrelationships between the factors—including positive and negative consequences and synergies with existing systems, programs, and structures—are equally, if not more, important than the factors themselves, the tool does not address them in a standalone section. Instead, questions pertaining to interrelationships and consequences are included as they relate to each factor.

Users should record responses to questions in the space provided below each question (expanding the space as needed) and record points allocated for each question and scores for each section in the right-hand column. At the end of each section, users can calculate a score for each factor and record summary comments.

Note: The tool may appear long but, depending on the scope of the program, one or more sections may be quickly completed.